For Roy Ratnavel, “started in the mailroom” is more than just a figure of speech. It’s the lead line on his résumé. His first job at a Bay Street investment fund was, literally, sorting mail. Before that, Roy had worked at a Toronto packaging factory. “My job was to stand there with a glue gun, and apply spray foam,” he tells me. “A board would come by on the belt, and I would spray it. It was 1988. I was making $3.50 an hour. I’m not even sure if they were paying me the legal minimum.”

“At night, I would clean buildings.” He gestures around at his twentieth-floor corner office. “Places like this.” On weekends, Roy had a third job as a security guard. His shift would start Friday at midnight and go to Saturday midday. Then again from late Saturday night to Sunday noon. Then back to the factory on Monday. “Then this one time, I’m standing there with my glue gun, next to this guy in his mid-’50s on the assembly line—I forget his name, but he just stood there muttering to himself all the time. And finally, I ask him, ‘How long have you been doing this?’ And he tells me, ‘Twenty years.’ And I saw a vision of myself turning into that guy if I stuck around. I knew I had to get out.”

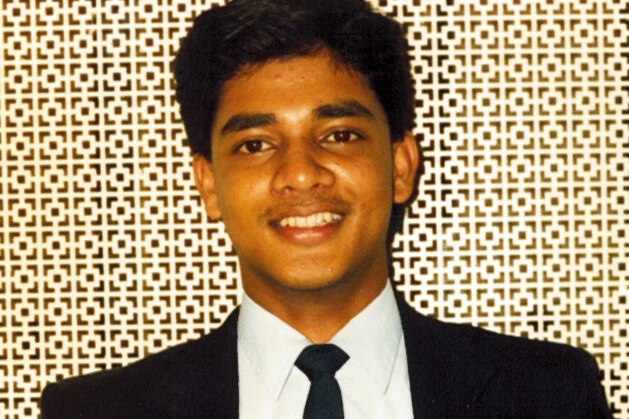

Roy was living with four roommates in a cheap apartment in the Toronto suburb of Scarborough. “They got one newspaper, the Toronto Sun—just for the Sunshine Girl—we never read it,” he tells me. “But that night, I flipped through the job listings, and there was one that said ‘Office Help Needed. $14K.’ I applied—even though I didn’t even know what ‘K’ meant.” His offer letter, dated February 16, 1989—twenty-seven years ago—now sits in a frame above his desk. Reports of discrimination against hard-done-by immigrants make headlines, and rightly so. But it is also important to celebrate the millions of newcomers who are living the Canadian dream.

Roy’s new employer was Universal Group of Funds, a small company that would eventually grow into CI Financial Corp., now the second largest independent investment company in Canada, with $155 billion under management. Roy’s ticket out of the mailroom came when he bonded with one of the company’s rising stars over their shared love of designer neckties. Roy moved to a sales-support position. Then to sales. Then to the Vancouver office, where he rose to manage the whole West Coast sales operation from Victoria to Winnipeg. And then, last year, back to Toronto, where he joined the CI Financial executive team as senior vice president and national sales manager. Quite a journey for someone who arrived in this country twenty-eight years ago with (US) $50 in his pocket.

For me to visit Roy in this office habitat was somewhat surreal—because so many of our discussions in life have centered around the horrors that took place in his native Sri Lanka. Our first introduction came when I was writing about that country’s civil war for the National Post, more than a decade ago, and Roy cold-called me to take issue with one of my columns. It was a subject he knew too well, having been targeted as a member of Sri Lanka’s minority Tamil population. His father was killed by pro-government forces—just four days after he’d put Roy on a plane out of the country. Roy, now forty-seven, hasn’t been back to Sri Lanka since.

When liberal Canadians express amazement that immigrants to this country could ever vote for conservative politicians, I often think of Roy. On his social media, you will find no sneering putdowns of Donald Trump or Rona Ambrose. As a career sales professional, he’s rubbed elbows with all sorts of Canadians. His Facebook profile displays shots of him in a cowboy hat, singing country karaoke in Alberta, side by side with images of him sharing fine meals in Toronto wine bars. Roy loves all corners of this country. Being a snob doesn’t get you very far in the sales world.

Nor does being thin-skinned. Roy has spent much of his career at CI traveling through small towns, giving sales speeches to rooms full of farmers and co-op managers. In Dawson Creek, Prince George, Smithers, Fort Nelson, Brooks, and Lethbridge, he’d often be the only non-white person in the room. In the early days, Roy still spoke with a Tamil accent (which has since faded to almost imperceptible levels), and would sometimes nervously alter his word choices to avoid embarrassment. “In Sri Lanka, you sometimes hear people switching their V’s and W’s when they speak English, so ‘market volatility’ would become ‘market wolatility.’ To avoid that, I would say ‘market gyrations.’” To break the ice, he’d make jokes that helped diffuse the social anxiety in a room—“like if a guy was named ‘James,’ and I called him ‘Jim,’ I’d say ‘Oh, you white guys and your complicated names.’”

And yes, Roy heard his share of politically incorrect comments. But the culture gap didn’t stop clients from buying what he had to sell. Amazingly, Roy says that throughout his quarter-century-long career in investment sales, he has never encountered what he regards as unambiguous racism. “I get into arguments with my Tamil friends about this,” he says. “Yes, I occasionally have heard insensitive comments like ‘Oh, you people love curry, right?’ But just because someone says something ignorant doesn’t make them some kind of bigot. If you want to be successful, you can’t go around being offended by everything. My dad had a saying: ‘You can’t control what people say. You can only control how you react to it.’”

“A lot of people I know will go to the lowest-common-denominator argument—‘I didn’t get there because of racism.’ But I keep telling them, ‘If you keep telling your children that there is some big shadowy white figure out there who is going to keep you down in life, they’re not going to try.’”

Things have changed since 1989, when Roy was the only non-white worker in his sales department. The CI workforce is now, as he puts it, a sort of “United Nations.” But Roy says the secrets to success are the same now as they were when he started out three decades ago: Be likeable, learn from your superiors, and—especially—work smart. (To this day, Roy still goes in to CI on Sundays. He never got over his teenage habit of working weekends.)

“I remember one incident, when I was twenty-one, and I was talking to Bill Holland in the elevator, who would eventually become chairman of the board—the same guy who plucked me out of the mailroom,” Roy tells me. “I was mumbling. And Bill interrupts me and says, ‘Speak up! The world will never hear you.’ Now, on the one hand, there’s a cultural thing going on there—because Tamils do tend to speak softly. But he wasn’t criticizing my culture. He was coaching me on how to get ahead in Canadian business. And I took his advice. Immediately. Because I’m not a fan of copying from C students. I like to copy from A students. And this guy was mega successful. And guess what? From then on, I spoke up.”

Because of his extraordinary success and stature within his organization, Roy gets asked about diversity a fair bit. But he says it’s not something he thinks about much—at least, not in the way the issue is framed by modern identity politics. “When I am looking for talent, I don’t have a lot of time for ‘We need to hire X people, we need to hire Y people.’ I just go out and hire the most talented people I can find. CI happens to be a very diverse workplace. But that’s not because I worry about skin colour. It’s because capitalism is the world’s greatest equalizer.”