Nuestras vidas son los rios

que van a dar en la mar,

que es el morir

—Jorge Manrique

My father had insisted

he did not want an American funeral,

by which he meant the cheerfulness

and the laughing at anecdotes

the living here tell about the dead.

No. He wanted throats constricted,

speech impeded, eyes rimmed red,

the room brimming with tears.

So I was unsure exactly

whose funeral I was attending,

but in the dream it fell to me

to place the LP of Piaf (or Brel?)

on a turntable beneath the bier

that held his plain pine coffin.

People milled about the church,

waiting for the service to begin.

Then David, a friend, himself dead,

had an urgent matter to discuss:

some properties he owned in Arizona

needed inspection and he wondered

would I be up for the ride west.

Whether this was the same current,

a tributary, or an entirely new dream

didn’t matter, for it carried me

out of sleep. My father’s funeral?

He was cremated. A mass held

at the Newman Center in Berkeley,

a reception at the Faculty Club.

A slide presentation brought him

from the time he was a baby,

helpless in his mother’s arms,

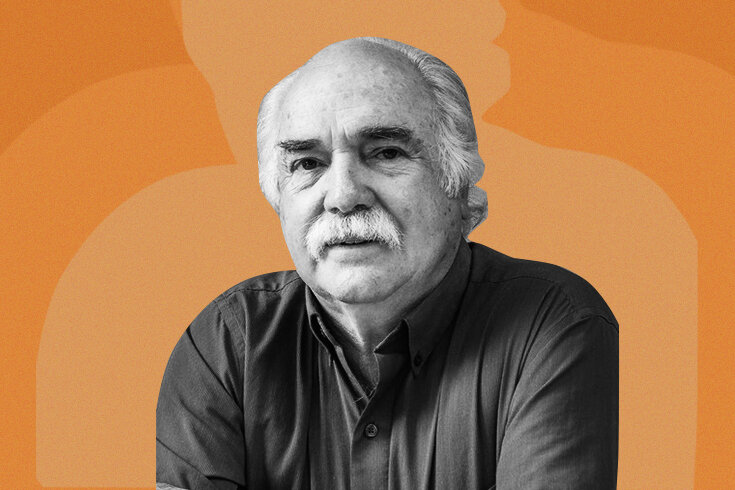

to his last days: a geographer

who had lost his bearings.

Grief was held in check

but haunted my mother’s eyes.

A month later, my brother and his wife

took the ashes to the Amazon,

poured them into a small clay pot

bought in the market at Manaus,

and went upriver to the Paraná,

near to where my father spent

a lifetime on research. Leo poured

the ashes into the river, sent us all

a note: Husband, father, grandfather,

great-grandfather no longer studies

the Amazon. He is the Amazon.

He told me that as the ashes

mixed slowly with the river,

a storm of bright, noisy perroquets

flew to a nearby branch.

I wasn’t there but like to think

the bird racket rose as disobedience

and hope it followed my father

as he swirled all the way downriver

to the mouth of the Amazon

and into the ocean beyond.