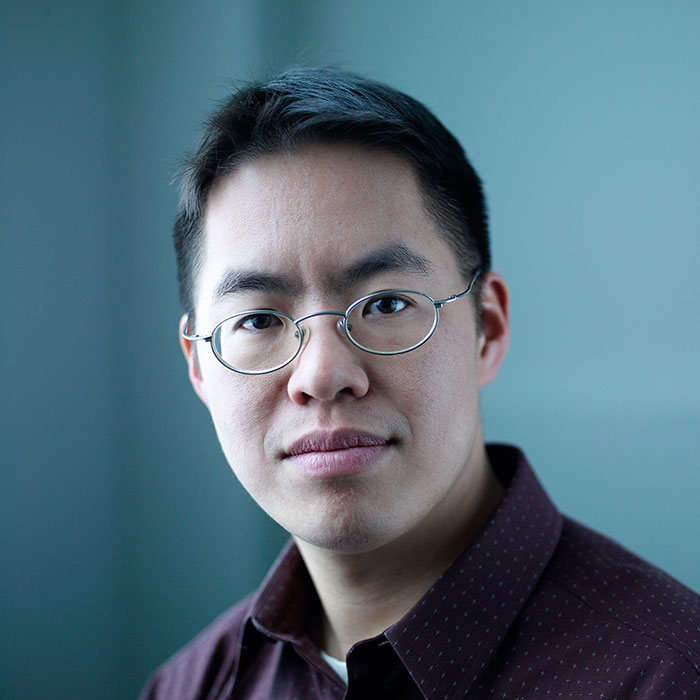

For a writer whose success has come from capturing the dramatic experience with a flourish of vivid detail, Dr. Vincent Lam is a picture of modesty. At a North Vietnamese restaurant in Toronto’s East Chinatown, dressed like Steve Jobs (Patagonia fleece, hiking boots, and oval wire-framed glasses), he speaks quietly and thoughtfully, keeping his hands rooted to the table. Throughout lunch, he never once raises his voice, waves his arms, or reacts with anything less than calculated composure. The conjurer of drama seems to indulge in none of it.

In April, Lam published The Headmaster’s Wager, his debut novel. It’s his first major work of fiction since his breakout success in 2006 with the story collection Bloodletting and Miraculous Cures, a masterful, gripping look at the lives of ER doctors based on his own experience as an emergency room physician; he currently practises twice a week at a Toronto hospital. Bloodletting went on to win the Giller Prize, vaulting him overnight into the Canadian literary firmament. That blockbuster was followed by two more books related to health care (a guide on flu prevention, and a biography of Tommy Douglas).

The Headmaster’s Wager is a sharp departure from that well-trodden white coat world: the sweeping Vietnam War epic draws on Lam’s own family history, and delves into the deep trench of the human soul at its most compromised, searching for redemption in an ocean of sin and temptation, pleasure and pain. He is placing a big bet on the table, clearly hoping his latest effort can transform him from a doctor who writes well about the medical world to a bold novelist who examines the human condition (and who can still shock your heart back into rhythm, if necessary). To do so, the reserved, highly calculating Lam has had to let go and embrace the greatest risk of his career, laying bare his ambition and his family history, and offering a glimpse of his private Christian faith.

The book was inspired by his larger-than-life grandfather William Lin, a hedonistic black sheep whom he first encountered through family stories. “My grandfather was always the tragic figure,” says Lam, who recalls how Lin’s gambling, drinking, and philandering (he had four wives and at least eight children) were presented to him as a cautionary tale.

Born in mainland China and educated in Hong Kong, Lin fled to Saigon during World War II to escape Hong Kong’s especially harsh Japanese occupation, and remained in Vietnam into the late 1970s or early 1980s, well after the fall of Saigon in 1975. Uncles, cousins, and parents spoke of the fortunes Lin pissed away at mah-jong tables, the powerful business contacts across Asia he cultivated and then squandered, and the opportunities for long-term prosperity and peace he missed, simply because he wouldn’t weigh the risks of important decisions (or ignored them). He made life-altering choices based on cocksure instinct and luck instead of logic.

Lam first met Lin at fifteen, when he visited him in Brisbane, Australia, with his grandmother, Lin’s first wife. His grandfather was a different creature than the stories told: a defanged tiger who lived in a retirement home, his only close family member a fourth ex-wife. Flashes of the old Lin appeared. He would bring a flask of cognac to dinner, knew how to order lavishly (his rule: most shellfish tastes better sautéed in cognac), and could charm strangers with his quick wit and kindness. The juxtaposition between the tragic figure who brought his family grief and shame and the heroic exploits the old man hinted at was captivating, especially to a studious suburban kid who lived by the straight and narrow. Returning home, Lam knew he wanted to write about his grandfather’s life. In a way, the book can be read as Lam’s attempt to creep out of his comfort zone and inhabit his grandfather’s skin, if not his desires—perhaps for the same reasons we have always been fascinated by anti-heroes, from Lucifer in Paradise Lost to Mad Men‘s Don Draper.

“His profile is intriguing,” allows Lam, “the gambling, the philandering.” But, he continues, “a big part of me also recognized that given life choices, I could have been very much like my grandfather.” In speaking to Lam, who gives the impression that he is not one to indulge in drink or drugs, or to take any uncalculated risk that could lead to a regrettable decision, it seems a far stretch to draw a connection between the two men. Born in London, Ontario, Lam grew up a studious, assimilated, churchgoing kid in suburban Ottawa. He met his Cypriot Canadian wife, Margarita, in an undergraduate history class at the University of Toronto, and the two proceeded through medical school together. She practises family medicine, and they live in Riverdale with their three kids.

At thirty-seven, his latest vice, if you could call it that, is collecting bicycles (he has eight) and spinning class, not only for the physical exertion, but also because it exposes him to music (rock, hip hop) that falls outside his usual jazz and classical. He bikes most places for transportation. He bikes in one place for recreation.

Knowing this, it’s surprising to experience the lush landscape of sin he has unleashed in the pages of The Headmaster’s Wager, using his protagonist, Percival Chen, as a confessor for many of mankind’s vices and, perhaps, some of his own unfulfilled impulses. The prose is thick with sensuous, fleshy detail: vivid descriptions of sumptuous foods, liquor like melted gold, flesh so tempting it upends lives, risk that constantly beckons, and violence so perverse it borders on the erotic.

Like Lin, Chen runs a school in Cholon, Saigon’s insular Chinatown, and that community, along with the violence, politics, and deceit of wartime South Vietnam, forms the booby-trapped backdrop of his moral trials. Twice, Chen’s blind arrogance casts his son into mortal danger, and twice he must beg, borrow, gamble, and lie to try to gain his son’s freedom. His decisions are supreme, his ignorance wilful, but as various wars rage in the square outside the doors of his eponymous English academy, year by year, his unwillingness to learn, or see, or hear the brutal reality surrounding him condemns those around him to their fates.

Chen is a tough protagonist to latch on to, and at times you just want to jump in and slap him. You can anticipate the consequences of his actions chapters earlier but feel powerless to stop them, and only in the end does Lam deliver a feeble dose of redemption. Unfortunately, Chen is all we have. There’s no one else to root for, as though Lam has deliberately deprived us of a convenient exit. The other characters play supporting roles, and aside from Chen’s ex-wife, a quick-witted Hong Kong shipping princess filled with resentment at the life he has saddled her with, they can feel one-dimensional: the sadistic Viet Cong torturer, a cartoonish John Wayne–talking American official, and the hooker with a heart of gold. Chen’s son, Dai Jai, whose fate is the entire book, comes across as little more than an offering for the altar, brought back when his sacrifice is again needed to further his father’s trials.

It is a credit to Lam’s talent that despite all this, you find yourself caring for Chen, because he is such an unrestrained evocation of our pure basal instincts, and a richly rendered character. Here is a guy who never says no, flying by the seat of his pants, from stupefying highs to despicable lows and back again, always filled with pride. It’s a hell of a ride, like watching train wreck after train wreck in slow motion—except you’re in the locomotive with the drunken engineer the whole time.

The plot comes together in the book’s most riveting scene, a high-stakes mah-jong game where the headmaster makes his fateful wager amid a flurry of Hennessy X.O and macho bravado that only borrowed money and time afford:

Ignore the worry, he thought. The fear of loss could make itself true. He must have only confidence. The métisse girl smoothed wrinkles from her dress with the back of her hand. Briefly, he remembered the money due to the Teochow Clan Association the next day. All of that was far away. He was short a few thousand from losses, no matter. He drank his cognac, sought its glowing assurance that he was posed for a big win. He could not stand up after losses and expect to win a girl. There was nothing attractive in a man who lost money and walked away.

Lam wrote the initial draft of the mah-jong scene during the market crash of late 2008, when the world’s debt junket gave way to the cold light of morning and an unpaid bill for trillions in sure bets from cocksure gamblers. Chen’s sins aren’t so far from our own. After all, what separates a table full of mah-jong tiles from a risky investment when all the signs point to a bubble? The line between poor judgment and wilful sin is barely there.

Though The Headmaster’s Wager is a story he has been exploring, in one way or another, for two decades, Lam struggled immensely with writing it. After Bloodletting came out, he denied that he was facing enormous expectations from the Giller win, which only increased his self-consciousness. He thought it would be easy, because the story and the emotions were his own, and all he had to do was tie them together with details. But he couldn’t wrap his head around the moving pieces. “Then, for the next three years, I felt horrible,” he says. “I felt, ‘I’m just not getting it right.’ I could imagine people saying, ‘Oh yeah, he was able to write Bloodletting because he’s a doctor. Look at what happens when he tries to write a Vietnam War novel.’ ” Only in the last year of writing did things click, and the character of Chen came to life on the page, separated from the actions and emotions of William Lin.

In the six years since Bloodletting, Lam’s writing has evolved. That book, which dealt with his daily environment and the experiences around him, was remarkable for its quick-moving prose and an almost Hemingway-like economy of words. But the details came easily for Lam, who was describing the sights, sounds, and feelings of his day-to-day life. For The Headmaster’s Wager, he had to revisit a part of his family’s physical and emotional past that he had only heard about.

“The world I wanted to write about no longer existed,” he says, “and there wasn’t a reference copy to look at.” He made two trips to Vietnam, in 2004 and 2008, which gave him a grasp of what he calls “sensorium”: the smell of fish sauce from breakfast pho vendors, the silken curves of women’s ao dai dresses. He tapped his family for additional details, such as how bribes were presented (in red envelopes) to power broking functionaries with seemingly powerless titles like Second Adjunct Chief Administrative Officer of the Department of Language Institutes. He also consulted some 100 books, many on the Vietnam War era, mining for such details as battle locations, the precise torture methods used by the South Vietnamese police and the Viet Cong, and the minutiae of people’s everyday lives.

“If I ever thought there were noble actors in that war, I was stripped of that notion,” he says. The South Vietnamese, the Viet Cong, and the Americans outdid one another with savagery and violence. Children betrayed parents, who betrayed friends and neighbours. Not even monks escaped with their bodies, or their morality, unscathed. No one comes out clean in the book, including the Chinese community in the Cholon quarter, where his grandfather and parents lived. Fiercely proud of their Chinese heritage, and disdainful of the native Vietnamese, Cholon’s residents lived in a sort of privileged purgatory, financing black markets and both sides of the conflict, playing advantages to survive. Everyone is out for him- or herself, and, as The Headmaster’s Wager shows, a zero-sum game ultimately leaves no winners.

Lam grew up a practising Catholic, identifies as a religious Christian, and regularly attends an Anglican church, which he and his wife settled on after trying out various congregations (from Baptist to Greek Orthodox) to find one that suited their needs. His faith clearly influences this book, which could be read as a judgment on weakness of spirit in the face of great temptation.

He insists he is not sitting in judgment. “I’m vaguely aware that those things are emerging [as I’m writing],” he says, “but explicitly I try to think about it as little as possible. I really want the story to come from character and events.” He also claims that the book is in no way a verdict on his grandfather, whose actions never affected his life in any negative way, but after talking to him it seems as though his faith, and his family history, may have seeped in more than he realizes.

Not long before he died, William Lin, who had dismissed religion for his whole life, accepted Christ and was baptized, a choice that left Lam wondering about its “convenience,” timing-wise. He concludes The Headmaster’s Wager with Chen’s own cleansing plunge, after he has submitted to a measure of repentance. It feels convenient in its own way, a coda of salvation capping several hundred pages of wallowing in mankind’s baser instincts (in wartime, no less), but there’s also the impression that his intention is genuine, and to end things any other way would have left the reader wallowing in the shadows forever.

After six years living in the world of his family’s past, Lam now sees the similarities and differences between him and the grandfather who inspired him more clearly. Both men are driven by obsessions, whether for gambling or bicycles, but, unlike Lin, Lam remains keenly aware of his impulses and how to manage the risk they bring. “I see the consequences,” he says. “I’d better not even taste it, because if I taste it I might really like it and get into it.” And yet, in the final analysis, the gambler, the churchgoer, and the writer are not so different. Each has a need to believe.

“Writing, anyone will tell you, [starts with] this lovely feeling when you get an idea for a book,” says Lam. “But then it’s hard. It’s a dark pit. It’s like dragging stones around a muddy field with your bare hands. Why would anyone do that unless they nurture a belief that they’ll eventually find peace with what they have done? Just like a gambler going through long losing streaks, you have to believe you have a story at the end of it, like a gambler believes he has a big win coming.”

This appeared in the June 2012 issue.