The slight fellow is wearing shades, but I know he’s studying me as we converge at Twentieth Street and Avenue D in the heart of Riversdale, Canada’s fastest-changing neighbourhood.

“Nice hat,” he beams, and I see myself in his mirrored aviators as we come around the corner of the liquor store, fall into step. We’re sporting similar fedoras with upturned brims, his scuffed white, mine brand new blue. He has a tattooed teardrop peeking out from under one lens, an eagle feather below the other, and a vicious cheek scar as if someone tried to cut him down with a machete at one point. I have neither ink nor scars of note. Frankly, he cuts the kind of figure I might have crossed the street to avoid not so long ago. But there’s a comforting critical mass of people who look like me on Twentieth Street now, and I make the acquaintance of Samuel Bruyere.

Bruyere looks Cree but sounds urban West Coast, confirms he has lived most of the last twenty years out in Surrey, British Columbia—there or prison. Like so many these days, he’s come back to Saskatoon.

“An attempt at family reconciliation,” he says brightly, but with an undertone that suggests it didn’t work.

We head west together, passing all the new businesses that have sprung up in place of the boarded-up storefronts that defined Riversdale for decades. New money is pouring into this perennially impoverished but “charming” old neighbourhood. Call it revitalization, gentrification, or something else, there are new espresso bars, a hipster co-working space, galleries, designers, the fine old Roxy Theatre saved from the wrecking ball. The face of the old neighbourhood remains, for now: pawnbrokers, surplus dealers, welding shops, the Saskatoon Friendship Inn that does free meals.

“What do you think of all the changes here in Riversdale? ” I ask.

“Yeah, man. The community that has been here for generations is being forced out.” Same brightness as before, same undertone. “Like Gastown in Vancouver.”

We reach Park Cafe, a popular retro diner, and—quite out of character—I suggest lunch. I’ve just spent a winter in California, and still carry a traveller’s open-heartedness.

Things may be changing, Bruyere says, sipping a Pepsi in a booth, his aviators set aside, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

“I was in a shootout in the fall, just over there in that house.” He points through the café window toward a place on Avenue F. “September 17,” he says, tells me I can look it up in the StarPhoenix, which I do later. His account is more vivid. He was shot three times, believes he survived by choosing not to wait for the ambulance but by grabbing a taxi that happened by the scene.

Bruyere turns out to be a high-ranking member of one of the Aboriginal gangs that are so prevalent in the West. He tells me that at thirty-eight, he’s had enough of “the lifestyle,” and wants to put his energy into halfway houses and his hip hop label. He talks of many things: the daily beatings he took at the residential school in Duck Lake; how First Nations and white politicians are in bed together nowadays; that if people want to understand gangs, they should look to the Irish Republican Army; how he recently buried a granddaughter on the Stony Plain reserve in Alberta.

For my part, I mention growing up in a suburb of Prince Albert in a well-off Irish Catholic family, with a residential school right at the end of my street; how I didn’t grasp until years later that we were living through apartheid. And something in Samuel Bruyere’s steady gaze, his slight but attentive nods, is deeply gratifying in a way I can’t name.

When we stand up to leave, I find myself foisting an awkward hug upon him. He’s got the aviators back on, is saying “See you around” over his shoulder. He’s out the door before I realize that our chance meeting has been made possible by a rare alignment of circumstances. In this booming city of mine, Riversdale is more than a neighbourhood that is gentrifying. It is a chance at healing an old wound. It is a knife-edge on which a city stands.

My wife, Marlene Yuzak, is looking out our kitchen window, hands on hips. April in Saskatoon and it is bloody snowing.

“Geez, we’re not in Santa Monica anymore,” she says.

“I was over in Riversdale today,” I say. “Maybe we should move across the river.”

“Why, is it warmer over there? ”

Just back from a three-month art residency in Los Angeles, my painter wife and I have decided to cash out of our grand old house near Broadway Avenue, Saskatoon’s original hipster street. But where to buy in this overpriced little boom city? In fact, why stay at all? Certainly not for the weather. I dislike how globalization unsticks people from place, magnetizes them to capital instead, turns us all into migrant speculators. But it is hard not to get caught up in a market.

We’ve lived in Saskatoon off and on most of our lives, permanently since 1991, and until recently it seemed the perfect balance of urbanity and small scale. Economically, the province lagged, or so it seemed next to Alberta, the young people ever slipping away. But the communal warmth was real, and the sheer distance to anywhere else made Saskatoon a little cultural island, a city of idealists in Sorel boots.

Saskatoon was intended as a utopia from the start. Fed up with their city’s vice and pervasive booze trade, Toronto émigrés first settled here in 1882. The Temperance Colonization Society hoped to build an alcohol-free society with their allotted twenty-one sections along the South Saskatchewan River. The teetotalling never took, but temperance idealism seeded this place.

Out of sticks and baling wire, the city gave birth to medicare and helped elect the first socialist government in North America under Tommy Douglas. It shaped collective, co-operative business models to forge an economy where the private sector refused to tread. Saskatoon has always sparked with quixotic visions and dreamed what it could do if it ever had a bit of pin money.

Now the great cufflinked hand of globalization has at last reached in and popped open our little city like a can of Great Western Pilsner at a summer barbecue. Uranium, oil and gas, potash, agricultural machinery, not to mention food—the world clamours for everything Saskatoon sells. As I write, Saskatchewan manufacturing exports lead the nation. Migrants pour in from places as diverse as Calgary and Cape Town. Economically, Saskatchewan grew 18.4 percent between 2006 and 2011, 6 percent more than the national average. The province, Tommy Douglas’s mousy rectangle of co-operatives and socialism, is now a capitalist baller. Who could have guessed?

Well, out here in Saskatoon, we mostly all did. Our big resource windfall was, like a prairie thunderhead, seen coming from afar. The only question was what kind of utopia we’d build with the wood.

In trembling anticipation, some of us organized Jane’s Walks and Critical Mass rides, and began a rich diet of visiting lectures by New Urbanists such as Ken Greenberg and Jan Gehl. They showed us their slides of Portland, Oregon, and Melbourne, Australia; of bike lanes in Groningen, the Netherlands; and it was all as bright as an IKEA catalogue. We rubbed our palms and thought of Calgary. For years, as we sat spectator to Alberta’s roughneck rise, we held Cowtown as the example of all the urban mistakes we’d never make when our turn at the resource table came.

So far, however, Saskatoon has only a painfully uninspired flab-ring of cul-de-sac sprawl to show for its success. The population figure surges, to the unquestioning glee of our popular fourth-term mayor, Don Atchison, a men’s clothier with a history of ducking gay pride events. Meanwhile, the density figure is plummeting toward 1,000 people per square kilometre, down from more than 1,300 in 2001. We build freeway bridges we cannot afford to connect to far-flung new suburbs that are old school before they’ve left the drawing board. We are building Calgary, all right—only it’s Calgary circa 1986.

Sprawl is a minor irritation, however, compared with Saskatoon’s more fundamental challenge, one it shares with many western Canadian cities: racial division. Because you can’t build utopia until you are done with apartheid.

Saskatoon was a town racially divided when Marlene and I first moved here in the ’80s—though it was nothing compared with the gritty mill town 150 kilometres north where we grew up, which had a much larger Aboriginal demographic and a residential school. With its grand, elm-lined streets, and the postcard railway chateau Bessborough Hotel set against a backdrop of elegant, sloping bridges, Saskatoon was like Europe to our eyes. We inhabited the lovely Tyndall-stone Gothic campus of the University of Saskatchewan, sipped our very first espressos, saw films with subtitles, drank in artful dives, felt we were somewhere. We believed the local lore that Saskatoon had more than its share of writers and artists, that our Mendel Art Gallery was the most visited in the nation.

“The Paris of the Prairies,” Leonard Cohen quipped from the stage of the Saskatoon Centennial Auditorium one night back in the ’80s. We knew he was teasing us just a little, but we clapped wholeheartedly.

Cohen wasn’t talking about the west side, however. As stark as the Tijuana–San Diego border, Idylwyld Drive cut the city longitudinally, and Aboriginal people were scarcely seen east of the medicine line. If you tried to cross it by walking the riverbank, the derelict A. L. Cole power plant and its gaunt smokestacks blocked your path. West-side avenues had no names, just letters. Alphabet City, as it is still sometimes called, was home to Cree, Saulteaux, Dene, and others who had poured off the reserves beginning in the late ’60s. There were certain non-Aboriginal ethnic groups, too, especially Chinese, Ukrainian, and Polish. Whereas the east side of town was nearly all residential, retail, or university space, the west side had the garbage dump, two power stations, two rail yards, grain terminals, the airport, and many industrial zones.

As a student I read John Porter’s classic, Vertical Mosaic, and books like it, and began to deconstruct the myth of Canada’s classless society. Our ethnicities were presorted into hierarchies, and every Canadian city overtly earmarked ghetto territory for those below a certain niveau. Aboriginals were permanently pegged to the bottom rung.

Riversdale was the first neighbourhood west of Idylwyld. Despite its hobbit name, it was a synonym for vice and danger. Its main drag, Twentieth Street, was known for its beery flophouses, warren of pawnshops, and highly visible sex trade.

Idylwyld Drive divides Saskatoon to this day, just as railway tracks, rivers, and highways divide other cities for similar reasons. Except that lately in Riversdale, some people are trying to erase the line.

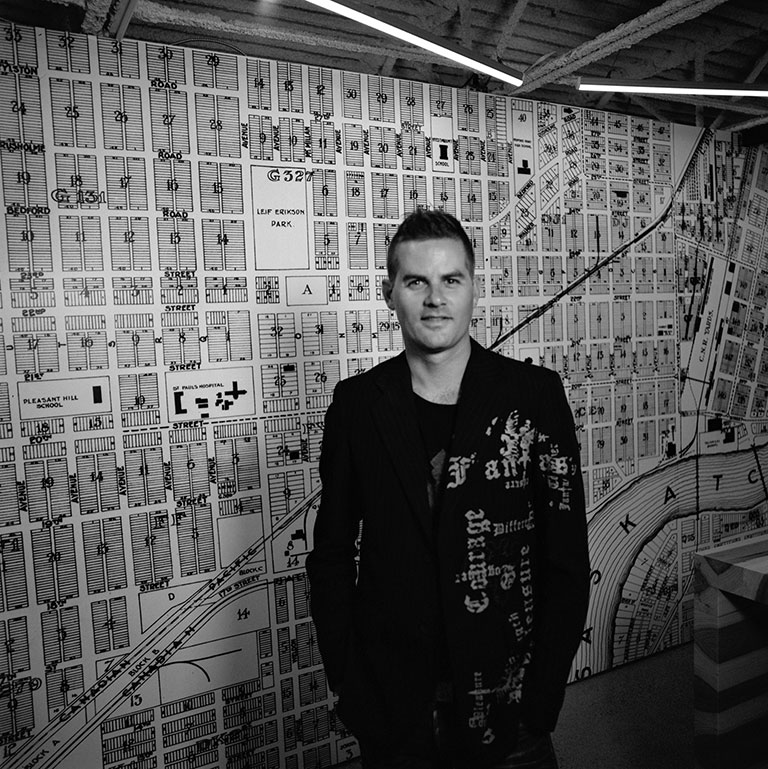

“It’s the best it’s ever been,” Randy Pshebylo says of the neighbourhood. “The level of energy, the numbers of young men and women buying businesses, putting their restaurants and stores here, the amount of cross-promotion. If I blindfolded you and put you in a cooler, you would feel it.” Pshebylo is the executive director of the Riversdale Business Improvement District, the agency leading revitalization. At fifty, he has spent half his life on the RBID board. And perhaps no one has worked harder than he has to promote and defend Riversdale. Even his Ukrainian moniker (pronounced shuh-buy-lo) trumpets west-side pride.

Pshebylo is a walking compendium of Riversdale statistics, oddments of research, Darwinian observations. He once sat all day in a lawn chair at the hellish intersection of Idylwyld and Twentieth to observe pedestrian routes between the Midtown Plaza mall and Riversdale. He references obscure planning documents like a rabbi citing Leviticus. Learning that a local sports store sharpened 30,000 pairs of skates a year, he calculated the area’s hockey mom–restaurant potential. He takes strange pictures when he travels—of curb designs in San Diego, California, light fixtures in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

“My fiancée calls me Rain Man,” he says, deadpan. He was a funeral director for twenty-seven years, and still exudes the empathy and gravitas of that trade.

“We’re taught in BID management that areas can become hardened into problem zones over time,” he says. “You need an element to go in and soften that up, and the people who are best at that are artists and the gay community.” At his urging, many arts groups have put down roots on Twentieth Street in recent years—French theatre company La Troupe du Jour, PAVED Arts collective and AKA Gallery, the Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra.

It was his idea to pair the symphony with the Roxy Theatre to present silent film classics under full orchestra, one he picked up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The 1930 Roxy is the last atmospheric cinema palace west of Winnipeg, its main auditorium decorated like a Spanish courtyard. It came within a week of demolition before Magic Lantern Theatres picked it up in 2005, and spent $1 million restoring it—probably the single greatest boon to Riversdale’s renaissance. Back in 2011, my son and I joined a packed house to watch Buster Keaton in The General. With the symphony sawing gleefully through the rambunctious score, the night indeed seemed a great miracle of rebirth for Riversdale. But one couldn’t help noticing the lack of Aboriginal people.

When I bring up the G-word with Pshebylo, he is ready: “Gentrification is displacement of one class by another, typically a rich one over a poor one.” Despite the current boom, he says, the numbers show Riversdale is years away from such eventuality. Commercial vacancy rates, which once sat mired at 46 percent, are still 13 percent. Home ownership stands at 65 percent in Saskatoon overall, versus 36 percent in Riversdale, and 28 percent in adjacent Pleasant Hill. The average home price in Saskatoon is $363,000; in Riversdale it is just $201,000.

“Here, we’re crawling upward,” Pshebylo says, “We’re just trying to get to average. There are no climbing values here that would displace anyone.”

Riversdale’s deep inventory of empty lots and derelict buildings ensures there is room to develop without uprooting tenants, he says. And far from promoting urban diversity, chronically depressed building values are the very drivers that turn landlords into slumlords, neighbourhoods into ghettos. His face clouds as he recalls the dead he has borne out of squalid, mould-filled dumps in his funeral career. “Some people might say a house like that is better than living under a bridge. I don’t know.”

Pshebylo questions the self-perpetuating nature of charity itself. “I’ve always maintained that there is money in poverty. There are executive directors in town making $30,000 a year more than I do in the name of poverty reduction.”

In one eight-block area of Riversdale, he counts seventy-two helping agencies—outreaches, ministries, soup kitchens—a number he feels is far too high. The sheer density of well-intentioned agencies only reinforces Riversdale stereotypes, and overloads an already struggling neighbourhood. “The food bank in Riversdale has clients every day from every postal code in the city.” The recently constructed Friendship Inn serves more than 1,000 free meals a day to a city-wide clientele. It is simply too many unemployed, disaffected people for one neighbourhood, he feels.

Meanwhile, he keeps working to bring employed people into Riversdale. The Edge and the Mosaic are two new low-rise condo projects that will put three dozen young working families where before there were empty lots and a drug house.

These are only appetizers compared with the Banks, a 145-unit complex to occupy vacant land next to the Saskatoon Farmers’ Market. It was Pshebylo who first made contact with its Victoria-based developer a few years ago. He skipped a scheduled tour of a Hastings Street needle exchange program in Vancouver, in favour of a pitch meeting with the condo developer, Chris Le Fevre—who made his urban renewal mark in that city’s Gastown and Victoria’s Old Town. Pshebylo sends me off with a copy of the Banks brochure under my arm.

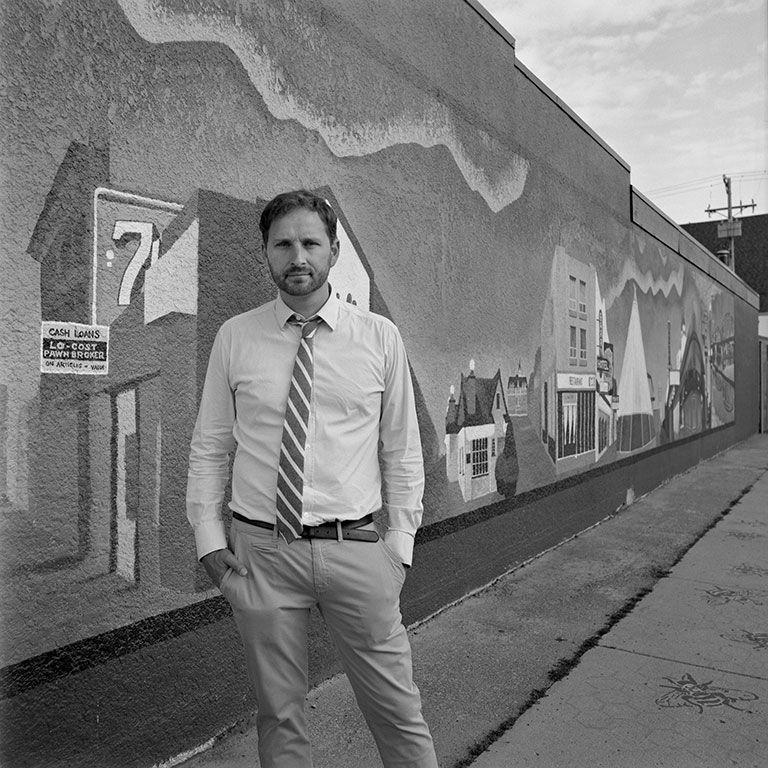

In the cafeteria of the community centre called Station 20 West, Marcel Petit—Metis filmmaker, youth leader, and self-described rabble-rouser of Twentieth Street—is railing against the “saviours” of Riversdale. We’ve never formally met, but we grew up within sight of each other—albeit in different worlds. He sometimes lived with his mother near my house in Prince Albert, had foster parents in Christopher Lake not far from our family cottage. By fifteen, he was on his own on Twentieth Street, and quickly slid into a “stupor of drugs and alcohol” that lasted until the new millennium. Now forty-five, he is known for his frank documentary Hookers, about the lives of five women who worked Saskatoon’s street sex trade—all of them his own relatives.

Petit is infuriated by the self-congratulatory logic some newbies bring to Riversdale, infuriated by the notion that the century-old streets are somehow a blank slate and that the mere infusion of capital into empty lots and vacant buildings magically overwrites complex social inequities. “People say, I’m going to buy these cheap houses and cheap buildings before the prices go up. And then they pretend they are saviours. You haven’t saved the world. Be honest about what you are doing. Say, I’m here to make friggin’ money.”

Old-school racism may be less overt now, he says, but old-world classism persists. The poor are migrating deeper into the west side’s alphabet of streets, to its less-fashionable suburbs. The street sex trade isn’t defunct, just diffused. The docket court still provides steady income for lawyers, judges, and jailers. “In Saskatchewan, there are three main industries—uranium, potash, and poverty.”

And Riversdale?

“It’s resilient. It’s been around for over a century. But the people who live there are what make it resilient and strong. If it’s all going to be about people wearing skinny jeans and having their $6 coffee, going to yoga, and buying their fancy bikes, you’ve lost the community. Which is what gentrification is about, taking away community.”

When I ask him how he’d feel if Marlene and I moved across the river—if we became neighbours again, as it were—he offers this: “I would invite anyone to go anywhere in the city. But don’t come over here and say that you’re going to make this old house pretty and that’s going to save the neighbourhood. Your guilt is your own shit.”

At home later that evening, I take out the Banks brochure Randy Pshebylo gave me. So far not even a hole in the ground, the Banks will house about 300 neo-urbanites in four interconnected buildings near the river. What their collective impact may be is hard to say. For now, all we have to go on is the brochure.

It is a twenty-page, nearly folio-sized, full-colour booklet combining architectural renderings and photos of what may be called “street life” in Saskatoon. Many of the models are people we know (it is still a small city), who are pointedly thirtyish. They ride fine bicycles, they paddleboard, they stroll with happy children afoot, they reveal artful tattoos. Not a single photo depicts winter. And, although it is hard to be absolute about such things, I think not one face is Aboriginal, save for the statue of great Chief Whitecap, in which the Dakota leader is seen counselling temperance pioneer John Lake on where to establish his riverside colony.

Chris Le Fevre, the developer, is ruggedly good looking in his aggressively Photoshopped headshot. He concludes his personal letter page as follows: “The development offers urban living for young and old and does not displace people, as so many developments can often do.”

Okay then.

“I was over there today,” my wife says. She means over in Riversdale. We are in our kitchen that badly needs an upgrade, having another in our endless series of talks about our housing future, whether we should move across the river or the continent.

“A guy was spitting on windows.”

“Huh? ”

“Spitting. He’d walk in front of those new stores, you know. He’d wait in front of the windows to make sure people saw him. And then he’d spit.”

“What stores? ”

“You know, on the first part of Twentieth. The nice new ones.”

“Geez.”

“Yeah.”

The first warm day. Marlene is arm-in-arm with our friend Lilly Wilson outside her rented house in the Westmount neighbourhood, under branches that are budding at long last. Every few weeks, we pick her up for coffee. She is the grandmother of a large clan that was one of Marlene’s client families back when she did contract social work for Family Service Saskatoon. Somehow we’ve stayed friends with Wilson, though our lives are separated by every boundary this city can throw between people: income, education, geography, race, age.

Now in her seventies, Wilson was born on the Sucker River reserve up by Lac La Ronge, drifted out to Toronto, married a white fellow, liked big-city life and its plentiful red streetcars. She got homesick one summer, came back to Saskatchewan to visit, and stayed. She’s recently had some lung cancer removed, says she is fine. But it can be hard to tell with her.

We always have coffee at Tim Hortons at F and Twenty-Second, which, in stark contrast to the trendy espresso bars of nouveau-Riversdale, is heavily favoured by Aboriginal customers and staffed by recent immigrants. Tim’s shares the parking lot with the Giant Tiger discount store, a retail cousin to the Northmarts that serve Canada’s North, with corporate lineage back to the Hudson Bay Company. The Health Bus, a mobile walk-in clinic, regularly stops here.

“So, Lilly,” I ask over Timbits, “what do you think of all these changes happening in your old neighbourhood? ”

“What changes? ” she says flatly. I’d warned her on the phone that I wanted to ask her about Riversdale, but see she is turned poker-faced behind her Iced Capp.

“You know, all these new people moving in, the new stores and restaurants.”

“I haven’t noticed anything,” she says. “I never go down there.” She means Twentieth Street, two blocks over, and I almost start to protest. City Centre Church, which she visits once a week, is practically within sight. But I manage to keep my mouth shut, and we stick to family topics.

After coffee, we follow her across to Giant Tiger, wait while she browses the spring clothes, picks up socks on sale, gets something frozen. The Tiger, which specializes in underserved urban markets, is often criticized for its poor-quality, over-processed food. But the prices are great, and it finds a way to hire Aboriginal staff. At least it is here, unlike Sobeys, Safeway, or Superstore.

It’s not until we are in the car that our old friend casually brings up the rising rents in the neighbourhood, how they make it impossible for her family—five people in a small bungalow—to find more space. “It’s greed,” she says, so softly I nearly miss it.

A few days later, Wilson calls us from a hospital bed. Pneumonia, she says when we go to visit. She’s so delighted to see us. I grasp at that moment, back when Lilly saw perfectly the changes overtaking her neighbourhood but chose not to discuss them out of respect for our delicate friendship. If push comes to shove in Riversdale and its environs, it will be people like Marlene and me ousting people like her. Why state the obvious? Better to enjoy each other while we can.

If Riversdale and all it symbolizes for race relations are just now at a sweet spot of ripe possibility, then what might be its dark antipode, the nadir? In a broad sense, the last quarter of the twentieth century was a lost generation for Aboriginal youth in Saskatoon, who by the ’90s were selling their bodies in the meanest kind of streets while the affluent east side looked away. But if you had to pin the low point in the city’s racial history down to its single darkest moment, maybe it was the frigid November morning in 1990 when Neil Stonechild died alone in a field.

He was a handsome and troubled seventeen-year-old Saulteaux youth, with a provincial wrestling title under his belt and bit of a drinking problem. At the time, the gruesome TV footage of a boy’s frozen corpse being pried from the snow in the North Industrial area seemed just one more bad chapter in Saskatoon’s violent west-side story, terrible yet forgettable.

Stonechild was never forgotten by his family and friends, who alleged he was last seen alive handcuffed in a police cruiser, cut and bloodied, crying, “These guys are going to kill me.” The StarPhoenix, the CBC, and even the Washington Post kept picking at the story—that the Saskatoon police regularly ran young Aboriginal suspects on “starlight tours,” purposely abandoning them in the cold on the outskirts of the city. It took fourteen years, an RCMP investigation, and a public inquiry to get at least some of the truth. It transpired that Stonechild was indeed in Saskatoon police custody the night of his death when the temperature hit -28.1; that his autopsy showed wounds inflicted by handcuffs; that police lied, tampered with evidence, and misled investigators in the case; that there were other unexplained deaths with similar circumstances; and that Darrell Night, another Aboriginal victim of a similar ordeal, survived.

Truth is one thing, justice another. The two police constables in the Stonechild death were fired. The two officers in the Night abduction case received eight-month jail terms. Beyond such symbolic gestures, the inquiry commissioner, Justice David Wright, delivered a stinging indictment of police in his summary, invoking Hugh MacLennan’s Two Solitudes and “the chasm that separates Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in this city.…The void is emphasized by the interaction of an essentially non-Aboriginal police force and the Aboriginal community.”

The Saskatoon Police Service would tell you it has come a long way since that terrible chapter a quarter century ago, and no doubt it has. But how many years does it take to close a chasm?

In 2012, I attended the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings into the residential school legacy when they came to Saskatoon. They took place in Prairieland Park, a sprawling trade-show facility on the exhibition grounds that could have held many more people than those who showed up.

Anyone who wanted to could share, and the testimony was effectively public domain. Mostly, it was residential school victims who went up. One man from my hometown told of having to perform oral sex on one of his keepers the very day of his arrival in the school dormitory, and of the phantom tastes and odours of this ongoing debasement that still overtook him decades later. An Innu woman from Quebec, speaking in whispered French, recounted how a nun informed her that her own language was of the devil, that her parents were savages, the nun beating her all the while. And so on.

All began bravely, all spoke through bitter tears before long, and a support person would creep onto the dais to provide tissue and a hand of comfort to the sharer.

In the audience, we also wept, less bravely, for our diverse reasons. For me, it was that I grew up three doors down from a residential school in a fine house with a red-carpeted dining room, where the occasional racist joke was tolerated. So far as I saw, none of us of the “dominant culture” was brave enough to speak up, myself included. Which was a failing of the TRC. That, and the too-empty halls.

At twenty-four, Erica Violet Lee might brag that she helped found a global protest movement. But, like most of the Saskatoon women credited with launching Idle No More at a Riversdale meeting in 2012, Lee is wary of the term founder. INM is only the latest chapter of an Indigenous sovereignty movement begun centuries ago, she says.

“Idle No More encompasses so many different people. There are groups operating in Sweden, in Bolivia. It would be irresponsible for me to believe I could speak for so many diverse people.”

Even if they stand on the shoulders of giants, the phenomenal rise of INM out of Saskatoon’s inner city has been as refreshing as prairie crocuses after a hard winter, and serves as a reminder that Saskatoon utopianism is alive and well. But don’t try to pin down specifics.

Idle No More was born at Station 20 West, the community centre that marks the boundary between Riversdale and Pleasant Hill. It began as a teach-in against the Harper government and its omnibus bill C-45. The bill inevitably passed, but Idle just kept moving—seemingly in every direction. Like Occupy Wall Street, INM has been criticized for embracing too many causes, for lacking a tidy platform amenable to the modern news cycle.

Me, I’m fine with that. Maybe the only rational response to omnibus bills is omnibus protest. Still, it would be fun to read an INM white paper on the future of its hometown, Saskatoon.

“We have organized a lot of flash-mob round dances in malls,” Lee offers.

The first of these took place in Midtown Plaza, Saskatoon’s flagship downtown shopping centre. Acting on a tip, mall security managed to bar some of the drummers and urged the merchants to slide shut their glass doors, presumably to repel looters. As the northern plains people have done on the banks of the Saskatchewan since long before the pyramids of Egypt were built, the smiling dancers joined hands and shuffled in a circle.

“It was the perfect, small, momentary action that is peaceful, that includes everyone,” recalls Lee. “That is what I think Idle No More is, this beautiful moment that burns really brightly.”

At a noisy back table in the Underground Cafe, I’m straining to hear a soft-spoken fellow. Like Tommy Douglas, he’s a bookish sort preoccupied with health care. And like Douglas, Ryan Meili keeps faith that the Land of Living Skies remains a crucible of change.

“Saskatchewan has a history of looking at a problem and saying, We can do it differently,” says Meili. The family physician, who attends at two progressive west-side clinics, teaches community health at the University of Saskatchewan, and daily confronts what he would call the social determinants of health—which aren’t exercise and cholesterol but housing quality, education level, and income. A decade ago, he moved to Riversdale to be closer to his patients, though the patients have since decamped further west. In his 2012 book, A Healthy Society, he lays out a plan for revitalizing Canadian democracy by making health outcomes the underpinning of all government policy—Quebec and Finland are already moving toward this model.

Riversdale also happens to be a stronghold of the provincial New Democrats, whose party Meili has twice come within a whisker of leading. In 2009, an unknown Meili nearly won the leadership using a crowd-funded campaign savvy in social media, stunning the party establishment. The NDP dropped over a cliff in the subsequent election, losing all but nine seats to Brad Wall’s conservative Saskatchewan Party landslide. In another bid last year, Meili came within forty-four votes of current NDP leader Cam Broten. He does not rule out a third crack—though the very future of the party of Tommy Douglas and Roy Romanow is far from certain in Saskatchewan’s bullish future.

Meili worries that the resource boom is turning the province from its co-operative, collectivist past, away from the inconvenient truth of poverty amid oil wells and mines. In its profound slump, even the NDP has distanced itself from its unsexy co-ops-and-credit-unions history. “So there’s a question. Are we really Saskatchewan anymore? I like to believe we are. Even within our right-wing government, I like to believe there is some grounding in that local history. But it is at risk. And Riversdale is a metaphor for that. We can just become like anywhere else—push people out when a neighbourhood gets hot. Or we can be something different, something more community minded.”

In 2013, he founded Upstream, a national, non-partisan organization headquartered in Riversdale and dedicated to building the healthy society he envisions. The name comes from a classic public-health parable about drowning kids in a river, and the expensive agencies that rescue them one by one instead of going upstream to see who’s throwing them in the water. Poverty Costs, Upstream’s first major campaign, showed that 100,000 of Saskatchewan’s 1.1 million people live in poverty despite the boom. This costs us $3.8 billion a year, much of it in health care.

“Douglas always said we didn’t go far enough with medicare, that we didn’t get to prevention. He talked about a second stage, getting at the causes.”

Meili believes reinvigorating the nation with a health-in-all-things approach requires bold strokes that are uniquely possible here. “There are two reasons why Saskatchewan is interesting. The first is our history of innovation. The second, which may be the cause of the first, is that we’re small. We can actually control things here. The scale is not too large. I’ve always thought it was the reason medicare was possible here. This little trapezoid makes a fantastic lab.”

Marlene and I are parked alongside a house for sale in Caswell Hill. It is the neighbourhood north of Riversdale, just as old and as charming, and brimming with what a realtor we met called “upside potential.” The city will soon decommission its nearby transit bus “barns,” will convert them into galleries and restaurants, and a pedestrian street is planned. At the moment, however, there are still boarded-up places within sight, tagged garage doors, a needle drop box.

The house is a teardown, might be condemned already. But the way the sun hits the property suggests possibility. Crystal Bueckert, the designer of many infill houses I like, lives nearby, and I could imagine one of her spare, flat-roofed concepts on this narrow lot. It would honour the past enough while being modern, energy efficient.

I’m not sure Marlene is quite feeling it. A police cruiser has pulled up to the apartment across the street. Two cops go in wearing black slash-resistant gloves, which means somebody is coming out in cuffs.

I step out, walk up to the vacant old house, which is placarded by both the health and fire departments. The name of an infamous local slumlord is printed on the cards. But the elms here are lovely. I’ve always wanted to have a corner lot.

Back in the car, I find myself making a pitch. Our place would have a basement suite—a livable, bright basement, mind you—with high windows that admit light and afford emergency escape. We’d have the main house, of course, but the bottom we could rent, maybe to a young family. We could use the income, and we’d be doing our bit for density, maintaining affordability. We’d be keeping the neighbourhood diverse, wouldn’t we? Marlene warms up to the idea. The price is low enough that we could resell if we change our minds.

But the realtor is impossible to reach. We cross over Idylwyld, and repair to the Woods Alehouse; over pints of 606, doubt creeps in. The price isn’t great, we decide, though we both know this is a dodge. Really we’re thinking about the medicine line that divides our city. It has begun to blur, but it is still there. At least there is no question as to whether we belong in our current house.

This appeared in the October 2014 issue.