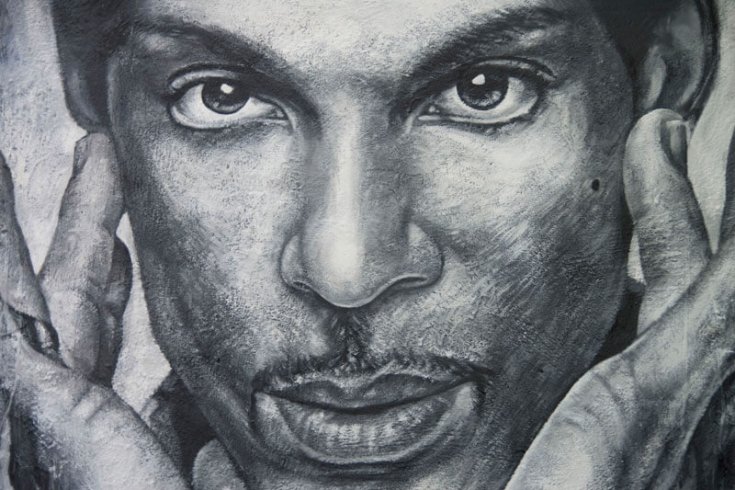

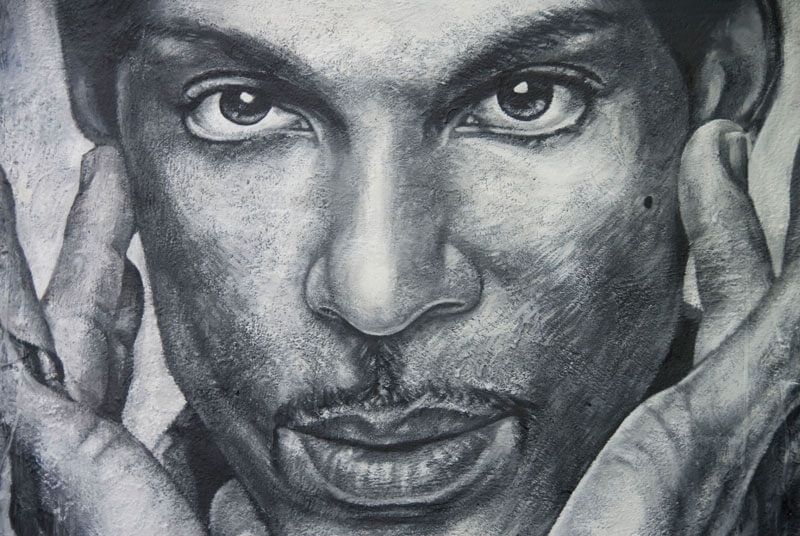

Yesterday, after hearing the news that Prince Rogers Nelson had died, my first reaction wasn’t to open my iTunes and pull up his discography, it was to track down and watch a dark, grainy video shot of Prince performing at Minneapolis’s First Avenue nightclub in 1983.

The first live performance of “Purple Rain” is incredible for a number of reasons. It was nineteen-year-old guitarist Wendy Melvoin’s first show with Prince’s backing band, the Revolution. The extended length of the performance makes for a slower build into its show-stopping moments, revealing new angles to a composition you thought you knew inside out. Yet the song still sounds exactly like the version you’ll find on Purple Rain the album, and with good reason: Prince was taping the show, and was so impressed by the performance that he used it for the recording itself. He would shorten it and add a few overdubs, but nearly all of “Purple Rain”—from the soaring vocals to the awe-inspiring guitar solo—was there from the very start.

I’ve often wondered what it would have been like to be in that crowd that night. At the time of the concert, Prince had only one top-ten single to his name; a year later, the film Purple Rain and its accompanying soundtrack album would make him a pop music megastar. In his 2014 book, Let’s Go Crazy: Prince and the Making of Purple Rain, Alan Light gives a detailed account of the concert, but more from the perspective of the band and the venue than the audience. Did they know they were watching an artist at the peak of his powers, taking control over a moment in pop music history and making it his own?

It’s one thing for a musician to have an impressive body of work over a lifetime; it’s another for their work to have a concentrated impact within a particular period of time. Critic Tom Ewing has written about the idea of an “imperial phase,” a term he borrows from the Pet Shop Boys to describe accelerated moments in a career in which an artist seizes authority over a cultural moment. Steve Hyden offers up a similar concept (albeit in more of a parlour game format) with his “Five Albums Test,” identifying artists who’ve successfully strung together five successive great albums in a row.

Hyden gives Prince a soft “pass” on his test (with reservations about both 1981’s Controversy and 1985’s Around the World in a Day), but Ewing suggests Prince might lay claim to one of the most impressive imperial phases in music. If we count the unreleased-at-the-time but widely bootlegged Black Album, Prince’s run from 1979 through 1989 includes eleven albums in eleven years. Two of them—Purple Rain and Sign o’ the Times—are rightly regarded as among the greatest records of their era, if not all time. There’s not one, but two double albums in the sequence (Times and 1999). The closest thing to a weak album in the chain is probably 1989’s Batman soundtrack, nonetheless a massive hit that further cemented Prince’s stature in both music and pop culture.

Taking into account both quality and quantity, Prince’s 1980s heyday represents a run of recordings that few artists in popular music history can match. You’ve got the Beatles, certainly, with ten great albums in seven years from A Hard Day’s Night through Let It Be. The Rolling Stones did seven in eight from Aftermath to Exile on Main Street. Depending on your taste for Pin Ups you’d have to include David Bowie’s 1970s discography in the conversation, and then there’s Neil Young, who like Prince can claim eleven impressive albums across an eleven-year span (1969–79).

Yet Prince’s 1980s streak is distinguished even among such company. For one, there’s the sheer diversity of the material itself: as the decade progressed, Prince’s already potent cocktail of funk, soul and R&B enveloped more and more elements into its mix, from the lean synths of 1986’s Parade to the dizzying smorgasbord of sound surveyed on Sign o’ the Times. Consider, also, that he wrote, produced and performed much of the material on records by associated acts like the Time, Vanity/Appolonia 6, Madhouse and the Family. Artists like the Bangles (“Manic Monday”), Sinéad O’Connor (“Nothing Compares 2 U”) and Chaka Khan (“I Feel For You”) turned his songs into massive hit singles of their own. And, absurdly, there’s likely much more where all that came from: even putting aside abandoned records like Dream Factory and Crystal Ball that eventually morphed into other projects, or the hundreds of bootlegged recordings that were leaked (some believe by Prince himself), those who worked with Prince during this time claim that the vast majority of what was recorded remains unreleased, hidden away in the Paisley Park vaults.

But what’s perhaps most remarkable about Prince’s decade-long run is that it flew in the face of where the music industry was headed. Michael Jackson, possibly the most iconic artist of the era, only released two albums in the 1980s; Bruce Springsteen and Madonna released just four each. With the aid of MTV as a new means of promotion and the increasing importance of international markets, the era of high-volume output—once thought of as a necessity for maintaining an artist’s presence in the marketplace—was being replaced by a system of release and promo resembling what we now expect as the modern album cycle. Excepting pop-factory productions (Rihanna from 2005–12, One Direction from 2011–15) and ambitious independent artists (like Ty Segall from 2008–present), the idea of releasing and promoting an album each year—let alone the sheer volume of music that Prince did in the ’80s—hasn’t really returned since.

For Prince, though, even an album a year wasn’t enough. This was one of the major points of tension between Prince and his label, Warner Brothers—a dispute which, at its most heated point in the 1990s, led to the artist changing his name to his unpronounceable male/female symbol and regularly appearing in public and onstage with “slave” written on his cheek. From Prince’s perspective, the label had no right to limit how much music he could release; the label, in contrast, was worried about overwhelming the market. “His attitude was, ‘I have a lot to say musically and I want to say it right now,’” long-time Warner publicist Bob Merlis told Variety this week. While we were working on (promoting) the second single from the current album, he’d already recorded the next album and wanted us to put it out.”

In hindsight, it’s easy to appreciate both perspectives. Prince’s post-1990 career certainly makes a good case for Warner’s argument: while he maintained his high volume of output—depending on how you count some of them, more than twenty-five albums between 1990’s Graffiti Bridge and last year’s two Hit n Run records—the material was inconsistent at its best and bafflingly mediocre at its worst. But listening back to his ’80s records, or watching that First Avenue performance, it’s almost maddening to think that marketing plans and release schedules might have limited our access to Prince at his peak. For nearly a decade, and against industry trends, we got to experience a rare combination of musical genius and musical prolificacy that produced a remarkable run of songs and albums that rightly ranks among the greatest of all time. How sad that we’ll never again get to hear them on stage, straight from the source.