First of July, Canada Day. It’s 2°C, and at lunch the six of us stand around in fleece and Gore-Tex discussing different kinds of hypothermia. There’s the insidious sort, where, after several days of complaining about being cold, the victims turn complacent and say they are fine. It’s the “I’ll just lie down in a snowbank for a short nap” kind of hypothermia. Then there’s the more overt, slap-across-the-face kind that would happen if one of our canoes tipped over. The water in the Back River is freezing, with big hunks of ice racing through it. Going over unexpectedly means only a few short minutes before losing consciousness.

We eat our bannock and peanut butter standing up, stamping our feet to keep warm. There are blocks of ice along the beach, and we karate-kick them to increase the blood flow to our toes and to hear that metallic, splintering sound. Two Arctic wolves have been following us all day. They howl forlornly from the distant ridge.

In 1834, the Back River, or Thlew-ee-choh (Great Fish River) as it was then known, had an evil reputation among the inhabitants of the eastern Canadian Arctic. When Lieutenant George Back proposed to descend its bone-chilling waters, Yellowknife chief Akaitcho cautioned strongly against it. Back didn’t listen; he was determined to fill in the remaining blanks on the map of the Northwest Passage. His second goal was to search for Captain John Ross and his nephew James, who had gone looking for the channel. They had been missing for five years and were presumed dead, probably locked in the ominous Arctic ice.

It is this historic 1,000-kilometre route that our group is travelling. We’re prepared, we hope, for the frigid weather, the enormous water, the remote location. Of the mighty Back, our guidebook says: Not for Beginners. We are especially curious about one of the other groups paddling the same route this summer—young women from a camp in Minnesota. They were flown into the headwaters several days ahead of us, but we’ve seen no sign of them.

After the last crumb of bannock has been demolished and the peanut butter jar thoroughly excavated, we’re back on the water to confront a long set of rapids, one of eighty-three along the route. The eddy line is sharp. Tim and I are the lead boat, and we paddle hard toward it. Our canoe teeters dangerously as we swing around, but we recover and pull in close to shore. Jenny and Drew are next. They paddle hard toward us—power is the key to stability in whitewater. Their position looks excellent, but when they hit the eddy they spin around on a dime. We watch, horrified, as the boat tips sideways and water begins to pour in over the gunwales. The whole thing happens in slow motion; a lengthy sideways lean that ends with Jenny and Drew bobbing in the foaming, boiling eddy, about to be swept downstream.

In a panic, we paddle toward them. Jenny is calling for help, her voice shrill and her arms flailing at the surface. When we get there—it takes only a minute but yes, truly, it feels like hours—they have enough strength to hook their legs over our bow and stern decks. Their heads are clear of the water, but their chests (and therefore their vulnerable internal organs) are submerged. Their core body temperatures plummeting, I paddle as hard as I can, trying to keep Drew talking while making sure not to whack his head with my paddle. “I’m okay, I’m okay,” he repeats, his pupils as big as the pancakes we ate for breakfast.

With 300 extra pounds attached to us, it feels more like paddling the Titanic than a canoe. When we finally get to shore, Jenny is shivering violently. There are big drops of water on the tips of her eyelashes, and her lips are bluish-purple. She strips off her clothes, and when I get her dressed and hug her she begins to sob. Drew, deep in shock and refusing to take off his drenched clothes, is running back and forth along the rocky beach. He changes direction and heads up the hill toward a herd of grazing muskox. One of them raises its massive, woolly head. “Careful,” Jenny screams at Drew, “those things charge!”

Once we’re sure we won’t be attacked, we make camp at the river’s edge. It takes Drew and Jenny hours to warm up. They huddle next to each other in sleeping bags like kids around a campfire. After mushy lentil stew we all go to bed. By ten o’clock the tundra is drenched in twilight, the sun like a door that a ghost could step through. The Arctic wolves howl and howl. A month before the trip, Tim’s mother died unexpectedly, and we can’t help but think that she is here, checking up on her son.

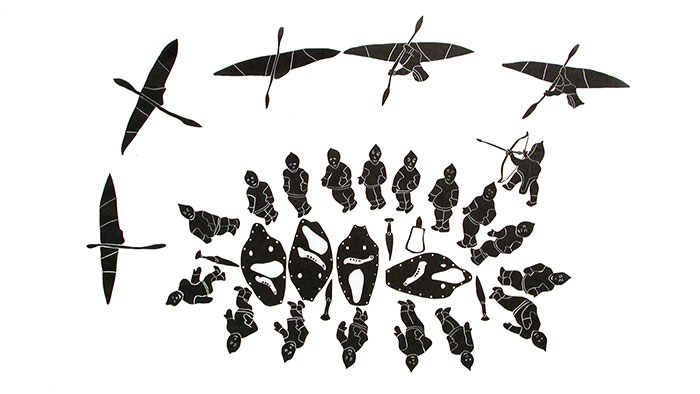

Outside of Baker Lake, the eastern Arctic interior is virtually unpopulated. This was not the case when George Back voyaged through the region. Then, there were three bands of Inuit (the word means “people”) living along the Great Fish River. Around Pelly, Garry, and Macdougall lakes lived the Ualiardlit, “the southwesterly ones,” and farther downstream were the “dwellers of that lying across,” the Haningajormiut. Near the mouth of the river lived the Utkuhigjalingmiut, or “dwellers of the soapstone place.” This final group helped Back portage his boat around the last rapids on his journey, between Franklin Lake and Chantrey Inlet on the Arctic coast—a generous gesture for which they were repaid with fishhooks and buttons.

While the descendants of the “people” now live primarily in coastal communities such as Gjoa Haven and Taloyoak, there are still signs of their ancestors along the river. We’ve seen many tent rings and pillars of rock embedded in clusters of smaller stones, formations about whose function we speculate endlessly. Primitive calendars? Messages for aliens? High on a ridge overlooking the tundra, we saw a cairn with several rocks rolled away. Inside, covered in lichen, was a pile of human bones.

July 10, night. We arrive at an island on Garry Lake. At the far end are the remains of an old cabin. It belonged to Father Joseph Buliard, a missionary who lived here in the 1950s and who was a friend of the Inuit. In October 1956, he hitched up his dogs and disappeared into a blizzard, never to be seen again. There are various theories as to his fate: most likely, he fell through the ice or got lost and froze to death.

Inside the crumbling mission we find a book about George Back. The Man Who Mapped the Arctic is in pristine condition, save for the cover page, which is decorated with seven signatures: the ghostly girls from the camp! They exist. Not only that, it is dated July 9. Yesterday. They are just one day ahead of us. We take the book and leave one of our own in its place.

The next day we hit a wall of ice. Rather, a wall of ice is delivered to us slowly, in gradations. In the morning, we paddle through chunks floating on the surface of the lake. When touched by our paddles, they make the familiar tinny, tinkling sound. When we stop for lunch, Jen adds a few cubes to our water bottles to cool our lemonade.

Back on the water, a cold wind blasts, subsides, blasts again. We paddle due east, and Tim stops to peer through his binoculars. He looks worried, and the object of his concern soon becomes apparent: the horizon begins to fill with a thin line of white. As we get closer we see ice—not the smallish hunks we’ve become accustomed to, but a solid platform, in every direction. We paddle as far as we can, until enormous pans emerge directly in front of us—with heavy ice beyond that, all the way to the horizon.

Pulling loads over ice is an activity we have only read about in the annals of historical expeditions. George Back’s dogs were outfitted in leather booties to protect their paws from the rough surface. Back himself stuffed two pairs of thick socks and buffalo skins under his moccasins. “Note,” he wrote in one of his diaries, “it is unnecessary to state that English Boots and Shoes are useless in winter.”

We step tentatively onto the ice in our “English” hiking boots. It groans and heaves when we drag the boats up behind us. The sun is out, and the ice sparkles white in places but is dark black in others, slicked over with a thin layer of water. It’s hard to tell which parts are firm enough to cross, and there are deep fissures where I can see down to the inky blackness below. In 1834, one of Back’s boatmen broke through and his body disappeared. One of his mates grabbed his arm and hauled him out, saving his life.

We proceed cautiously and, after several attempts, find a system that works: we make like dogs. With ropes attached from the bow of the boats to carabiners on the back of our life jackets, we trudge forward as though hitched to sleds, dragging our cargo behind us. It is gruelling work, and to pass the time I ask Tim about his mother. He tells me about giving her eulogy, standing at the front of the packed church for several minutes before being able to choke out any words.

By late afternoon, the ice is sloppier underfoot, and we have to jump between floes, retreating quickly whenever we feel them begin to sink beneath our weight. Drew and Jen are just ahead of us, while Jenny and Levi take up the rear. Tim gasps, and I look up to see Drew going through. We abandon our boat and hop across the ice pans toward him. By the time we get there, Drew has managed to haul himself up over the gunwales of his boat. He’s silent, breathing hard, and won’t speak. Far away, the ice makes a loud crack, like the sound of a gun going off.

Once Drew recovers we continue on, making good progress through the afternoon, half expecting to run into the young girls from the camp. But there are no markings, no suggestion that anyone has travelled this route before us.

On July 26, we arrive at the top of Rock Rapids. Twelve kilometres of ferocious whitewater, culminating in the plunge of Sinclair Falls. I wonder, is it named after Back’s Metis steersman, George Sinclair? We read Back’s description in The Man Who Mapped the Arctic: “The rapid foamed, and boiled, and rushed with impetuous and deadly fury…it was raised into an arch; while the sides were yawning and cavernous, swallowing huge masses of ice.…A more terrific sight could not well be conceived.” I am navigating and pass the map to Tim for his corroboration. To get swept down here would be fatal.

We stop for the night. As we pull over, we spot a small beach at the very top of the rapids with two overturned canoes pulled up onto it. It is a strange place for someone to camp, so close to the dangerous chute, but we set up our tents without giving it too much thought. Next to hypothermia, mushy lentil stew is our biggest enemy. During dinner we’d welcome a distraction from visitors, but no one arrives. The next morning we portage one load of gear around the first section of Rock Rapids. When we get back, it’s almost noon, and the overturned canoes are still there.

We hike over to the other camp. The site has been abandoned. There are no tents or personal gear. Three food packs have been sloppily closed. The two canoes have the girls’ camp name written across them in bold black letters. Where is the third canoe? A single boot sits in the middle of the beach.

No Arctic explorer has achieved such mythic status as John Franklin. In 1820, George Back was a midshipman on Franklin’s first Arctic land expedition. The crew suffered in a year when the caribou were scant and the winter fierce. Akaitcho, the Yellowknife chief, said to Franklin and Back, “The world goes badly. All are poor. You are poor. The traders appear to be poor. I and my party are poor likewise…I do not regret having supplied you with provisions, [however], for a Copper Indian can never permit a White man to suffer want on his lands without flying to his aid.” Magnanimous. Statesmanlike. But fourteen years later, as George Back’s own party pushed out into the headwaters of the Thlew-ee-choh, Akaitcho said that he would not risk his men’s lives to help the expedition. The Great Fish River was too dangerous, its waters too wild, its shores characterized by bands of unpredictable “Esquimaux” and a vicious Arctic winter that could arrive by the middle of August. “I have known the chief [Back] for a long time,” Akaitcho lamented, “and I am afraid I shall never see him again.”

What has become of the girls’ expedition? They began their trip with three boats, and now there are just two. The third, clearly, has tipped at the top of the deadly rapids. If the remaining girls are wandering across the tundra, missing half of their gear, they will be in serious distress. That is, if any of them are still alive.

We have a satellite phone reserved for emergencies and decide to call the rcmp in Yellowknife to report what we’ve found. We can’t get a connection; the telephone won’t work, we realize, because we’ve travelled too far north and are out of range. Panic starts to set in.

We spend the rest of the day slowly making our way downstream. Back’s description of the foaming and boiling water is accurate. With all the portaging, we manage only a few kilometres before making camp again. It’s terribly cold. I’m wearing two pairs of long underwear, fleece pants and jacket, a fleece vest, Gore-Tex pants and jacket, a down vest, a toque, and mitts.

We decide to search for the missing girls. There’s a discussion about who should head in which direction. Tim has been grieving his mother’s death, and Jenny asks if he’s prepared to find a body. He hesitates but then says that he is. I take the shoreline and Tim the ridge. “Hello!” we yell. “Hey-oh!” The shore is lined with rocks and boulders, with deep crevices between them. We look down into each one, hoping not to find bodies. Tim scans the edge of a wide bay with his binoculars. We see something at the same time: a piece of green material floating in the shallows. It could be a shirt, or…We run toward it, scrambling awkwardly over big slippery rocks. We are relieved to find it’s only a canoe pack, soaked through and heavy. There is a small stuffed moose clipped to the outside—the camp’s mascot, we think. We look at each other and don’t say anything. Tim throws the pack up over his shoulder, and we head back upstream.

Later, we pull each item out of the drenched pack. Makeup, romance novels, too many pairs of shoes: these girls were clearly not prepared for the Arctic. There’s also a wallet, a collection of rocks, and a diary that we skim through to help determine the group’s location. It is filled with lengthy reminiscences of boys back home, followed by a description of the missionary island in Garry Lake where we found their copy of The Man Who Mapped the Arctic. Is the child who owns this gear huddled together with her friends, freezing cold, somewhere out on the tundra, or is she dead? The last entry is dated July 22, four days ago. It ends with the words “Life is great.”

Franklin’s ill-fated expedition got stuck in the ice off the west side of Victoria Strait, northwest of King William Island. Eventually, his men departed from the ship in every direction, searching for the mouth of the Thlew-ee-choh. We know now that the river wouldn’t have helped them, given their scanty provisions, but as we search the tundra for the girls we imagine the men of so many different historic expeditions, eating “tripe de roche” (lichen scraped off rocks), and sucking at the leather of their boots for nourishment.

What is it that draws us here, that has drawn others before? “There is something exciting in the first start even upon an ordinary journey,” the prolific Back wrote in his 1834 journal. “The bustle of preparation, the act of departing, which seems like a decided step taken, the prospect of change, and consequent stretching out of the imagination, have at all times the effect of stirring the blood, and giving a quicker motion to the spirits. It may be conceived then with what sensations I set forth on my journey into the Arctic wilderness.”

Several days pass. We awake to a shrieking wind inside the tent vestibule. It’s too windy to portage, and the water is too frenzied to paddle, so we stay put, shivering in our sleeping bags, playing euchre and dreaming of warm baths and coffee shops. Also, alcohol. Cooking is an ordeal that requires all three boats being propped up as windscreens. We eat as much soulless lentil stew as we can manage, then cut a quick retreat back to bed. At night we hear the wolves, howling at each other from the far ridge.

On the third morning that we’re stuck, Tim and Drew decide to walk across the peninsula to check out Sinclair Falls. They return with another pack which, like the first, was floating in the shallows at the river’s edge. We open the soaked bag to find more makeup, arts and crafts supplies, more romance novels, and, incredibly, a satellite phone. We dial the rcmp.

A disembodied voice emerges from the receiver and floats eerily out onto the barrens. We explain that there has been a serious incident on the Back River. “Who was involved? ” the search and rescue coordinator asks. We open the girls’ book, The Man Who Mapped the Arctic, with the seven signatures on the front page, and read out the names. There is a long delay and then the phone disconnects. When we call again, the coordinator says that he knows about the accident. Somehow the girls—whose boat had indeed capsized—were able to get to shore before going over the waterfall. We are delighted and also amazed, just as George Back must have been on discovering that John and James Ross, presumed dead, had been rescued.

The girls not only had a satellite phone (sucked down the rapids along with their canoe) but another emergency locator device with them. They must have known that a rescue would cost thousands of dollars, but there was no choice. Without their gear, they would die. A helicopter had already arrived and flown them all out, cold and scared, to Baker Lake.

Franklin had no such luxury.

We decide to carry on. Several days later, at a point where the river widens, we see a red boat at the edge of the shore. We expect a tent and a person to come into view, but as we draw closer there is only the abandoned canoe, with the now-familiar camp’s name written in bold black marker across the bottom: an empty shell, a symbol of what has happened to so many expeditions before ours.

We decide to try to bring it back with us, and Tim attaches it to our boat with a rope. This works well initially, but he and I slowly start to fall farther behind the others, the dead weight of the second canoe dragging us back. It’s no use. We decide to cut it free, to continue the rest of our journey without it. There is a strong current, and we have a moment of silence, watching it drift ahead, the empty boat of history, flowing out alone to the sea.