At the moment of Confederation, Montreal controlled two-thirds of the country’s wealth and despite John A. Macdonald’s tipsy, heroic efforts at national unity, it remained a city of brilliant divisions: French and English; Protestant and Catholic; the Scottish commercial aristocracy and the Irish labourers who worked in their factories and mills. The Scots lived in the impressive, architecturally eclectic stone mansions of the Square Mile that were built with fortunes made from furs, shipping, flour, and beer. These were tough, often uneducated, ingenious men who imagined the new country with a mixture of nobility and larceny. Down the hill, on the regularly flooded streets of Griffintown, amid outbreaks of typhoid and violence, the Irish saw it merely as refuge. To the east were the francophones with their churches and history, who saw the country as a missed opportunity.

Montreal has the natural divisions of a political convention, and a marvellous political pedigree. It was the scene of the Pacific Scandal that brought down Macdonald’s government and the sponsorship scandal that sank Paul Martin. Montreal is where Brian Mulroney’s team went to the Old Brewery Mission and signed up a busload of addled, homeless supporters in exchange for free beer—and finished twenty-seven votes ahead of Joe Clark as a result. Former Quebec premier Maurice Duplessis distributed jobs, whisky, appliances, fear, and salvation to the working poor of Montreal for almost two decades, getting out the vote with the dark zeal of a missionary. Montreal has seen Drapeau’s folly, Trudeau’s patronage, and an army of bagmen exiting the Ritz-Carlton’s Maritime bar into the night, a town where politics has the collective memory of a killing floor. It was Montreal that D’Arcy McGee was pining for in 1868 after giving a midnight speech in the House of Commons on the merits of Confederation, minutes before he was gunned down in front of his Ottawa boarding house. Mulroney retreated to Montreal after decimating the Conservatives and became a bagman himself, leaving the Queen Elizabeth Hotel with Karlheinz Schreiber’s cash. If it was no longer the most powerful city, it remained a seductress, the locus of deals and good times, and Quebec remained the political prize, the key to a majority.

The Montreal to which the delegates came in the last days of November was basking in record temperatures and jokes about global warming. The candidates came with their separate versions of what the Liberal Party was. The listless tenure of Paul Martin hung like low smoke in the hills, his leadership largely indistinguishable from middle management and tainted by the sponsorship scandal. Jean Chrétien had overseen the country with great cunning and little imagination, a folksy, ruthless caretaker who had slain the deficit and maintained power. The greatest political strength of the party had been the profound disarray of the conservative movement. The Liberal Party has always been a lucrative middle ground, so lucrative that the Liberals campaigned on the notion of the happy medium in the last election, offering unpalatable opponents as the central reason to vote for them. In Montreal they were assembling the Liberal Frankenstein, stitching new ideas onto salvageable party history.

Inside the Clockwork Orange architecture of the Palais des congrés, with its wide white hallways and oversized graphics, there were banners of past Liberal leaders hanging from the rafters like hockey heroes, starting with Alexander Mackenzie, the prudent former stonemason who had quit school at fourteen, a teetotalling Presbyterian to offset Macdonald’s excesses; then Edward Blake, who wasn’t elected prime minister; then the first giant, Wilfrid Laurier; and Mackenzie King, no giant, but made large by history and sheer numbers—prime minister for twenty-two years, leader of the party for twenty-nine, his innate loopiness balanced by a light but sure hand on the tiller; the avuncular Louis St. Laurent; another giant in Pearson; followed by Trudeau, who got the loudest cheers at the convention; then Turner, in office three months, a casualty; and Chrétien, a leaner, meaner King. And finally Martin, his two years in office already undone by Stephen Harper and the Conservatives (the national daycare program, the Kelowna Accord), he is remembered more fondly as a finance minister. It was clear that the salvageable history lay in Laurier, Pearson, and Trudeau, but it was unclear what would be tacked on to it.

The north foyer, a large open space that stared upward to long escalators, was the initial battleground, the place where the high-school tribalism of convention politics was first staged. In the first few days, amid perspective plenaries, statutory-compliance workshops, and fundraising sessions, the different tribes occupied the foyer in loud, demonstrative shows of support and the first preenings of mating: we are the strongest, come and join us. Stéphane Dion arrived, buoyed by his supporters, shyly basking in the adulation as they pumped their placards and chanted his name. He looked genuinely surprised that it was all for him.

Dion’s slightly weedy academic mien had grown on the electorate in the months leading to the convention. He was being tentatively embraced in Quebec and had enjoyed fleeting moments of genuine statistical possibility, but he came to Montreal in fourth place. I had interviewed Dion in September, after first watching him on television, a medium that squeezes his intellect into unsnappy catchphrases. Dion whipped through his Three Pillar plan—economic prosperity, social justice, and environmental sustainability—as the host pleasantly admitted he would never vote for him. Afterwards, Dion sat down and expanded on his views in professorial detail, explaining his virtuous circle, a sustainable government for the twenty-first century: the forward-looking environmental policies would stimulate industry to respond with innovative technology to produce less-polluting products, and the health-care system would, in time, benefit from fewer patients as the chemicals and toxins that haunt our every step were reduced and removed. If he was without charisma, there were flashes of wit. He was shouldering a little of the baggage from the previous administration, was its chief advocate (“We made the difficult decision to put the fiscal house in order”) and occasional critic (“We could have done more”). In the leadership debates his passion tended to sound shrill, and his meticulous policies were received as hectoring rather than deliverance. But who has the most experience, he asked; who has the best policies, and who has had to make the fewest apologies?

Gerard Kennedy’s people had white kerchiefs with GK on them and they stood around their leader in the north foyer chanting those initials, prompted by a designated maestro. Kennedy spoke to them in brief snippets about renewal as Justin Trudeau flanked him, a Kennedy scarf around his neck.

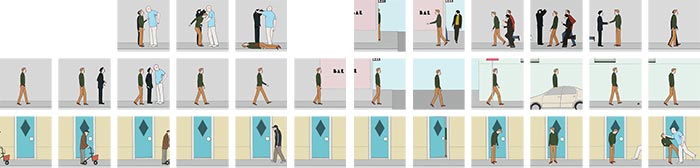

Kennedy came as a potential kingmaker and as conciliator, mending rifts in the party he hoped to inherit, a diplomat who was treading carefully toward a New Liberalism. Hanging back, he let Dion and Bob Rae tear at front-runner Michael Ignatieff. While campaigning, Kennedy had gone to Ryerson University in Toronto to talk to business students, celebrating his relative youth among the future managers, moguls, and hustlers, who on that day were slouched in low-cut jeans, Tibetan symbols tattooed on their lower backs, checking their BlackBerries and observing Kennedy with a sense of discovery. Voter turnout in the eighteen- to twenty-one-year-old bracket was 39 percent in the 2004 election, and statistics indicate that the tendency not to vote becomes ingrained and follows young voters as they age. They remain a politically lethargic but coveted group. The media outnumbered the students, the event less about reaching out to students than showing the televised image of reaching out to students. Kennedy told them that the New Liberalism embraced an entrepreneurial culture and that Canada needed to embrace it as well or risk being left behind. He was forty-six years old and appeared content to stare at his political future shimmering on the horizon like Mecca. Michael Ignatieff had courted Kennedy and left disappointed. Dion dined with him, and they fashioned a tentative pact. Dion was a francophone Quebecer; if he won, following Liberal tradition the next leader would be an anglophone from outside the province. Kennedy was of the West, where money and power were shifting. As he reminded delegates, it was time to stop spotting the Conservatives eighty seats west of Kenora every election. He put forth little policy that could be attacked and concentrated on being a statesman, a leader-in-waiting.

Bob Rae’s supporters, like Rae himself, were the most subdued. Rae brought the sensibility he had displayed as premier of Ontario, a sensibility he had dragged through the towns of Ontario like a cross, though in nostalgic memory Rae’s compassionate confusion fared better than Mike Harris’s Dickensian putsch. His candidacy was one of faith rather than policy: he is a decent ethical man and he will lead a decent ethical government. In political terms, Rae was reminiscent of Jimmy Carter, a good man who magnified the complexities of governing an ungovernable country and who aged visibly under the burden, frightening Americans, who quickly retreated to the calming void of Ronald Reagan.

But on the road to Montreal, it was Michael Ignatieff who was the centre of the play and, like Hamlet, a presence even when offstage. His ideas were publicly challenged, his commitment questioned, his citizenship in doubt, his liberalism mocked. Like Hamlet, Ignatieff was given to grand speeches, was at times contradictory, a prince who wondered if he was a man of words or a man of action. He was the early choice of 30 percent of the delegates. “He’s lov’d of the distracted multitude,” the king said of Hamlet, “who like not in their judgment, but their eyes.” Ignatieff had all the qualities that make a prince attractive: he is articulate, with a certain loftiness, and a sense of political destiny that occasionally, and cautiously, evoked Trudeau. Ignatieff had lived in a dozen places, a citizen of the world, self-contained, but he was now, he said, looking for home. “O God,” Hamlet laments, “I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams.” And Guildenstern answers, “Which dreams indeed are ambition.”

“I don’t think Michael knows who he is,” a Rae delegate told me. If he doesn’t, it isn’t from a lack of searching. Some of his books (The Russian Album, Scar Tissue, Blood and Belonging) deal with the notion of self and sense of place. And finding Canada’s place, a staple of Liberal conventions, was voiced at the Palais in the Hamlet-like lament: who are we in the world?

“Traditional Canadian peacekeeping met its Waterloo in Rwanda,” Ignatieff had told a crowd in Saint John, New Brunswick. The truth is, we are a middle power with an underfunded military. He added an international realpolitik to the softer Liberal line. “To defeat evil, we may have to traffic in evils,” he had written in the New York Times Magazine, engaging the issue of terrorism as a public intellectual and finding relatively few voices willing to join the debate. On the Stop Iggy website, disgruntled Liberals warned that Ignatieff would “destroy much of what constitutes the core of Liberal Party policy for the last century” though it could be argued that Liberal success rests in the absence of a core, in the Mackenzie King-like ability to co-opt and adapt and float toward a shifting centre.

Ignatieff’s occupation of the north foyer was Roman in its pomp and in its numbers. Phalanxes of supporters milled at the base of the long escalators, signs at the ready. Down the escalators, in waves, came supporters in different-coloured T-shirts—green, sienna, pink, and red—followed finally by Michael, descending to the masses, waving and smiling as they chanted, “Mi-chael! Mi-chael!”

Ignatieff’s muscular Liberalism was refuted by Dion and criticized by Bob Rae as “Harper lite.” Former Liberal cabinet minister Lloyd Axworthy obliquely accused Ignatieff of being an apologist for the Bush administration and its “borrowed and failed ideologies.” Ideology itself was in bad favour. In an interview Rae said, “I don’t think the country can afford to have deeply ideological parties. I find that ideology is usually a pretty lousy foundation for governing.” He criticized Harper for having the most ideological government in the country’s history, a divisive and Darwinian administration that ate the poor. Rae advocated openness and flexibility. Instead of ideology, then, a narrative.

There was much talk of narrative in the Liberal camp. They had paid one of Bill Clinton’s main strategists, James Carville, a rumoured $50,000 to come to Toronto and confirm to 1,200 Liberals that voters don’t want a litany; they want a story. In that Louisiana drawl, Carville offered George Bush’s story as example. “ ‘I was a drunk, I was transformed by the power of Jesus Christ… and I’m going to fight the terrorists in Iran and the homos in Hollywood.’” The Liberals hadn’t needed a story for some time, borne as they were by benevolent historical forces, by their populist appeal to everyman, and by the splintering of the conservative vote. But now the Conservatives had a narrative. “Mr. Harper’s narrative is a bad story for Canada,” Ignatieff said. “Beating Mr. Harper means defeating his narrative.”

The Harper narrative is a mélange of dense policy, simple gifts, and rigid ideology. There is a little of George Bush’s America (the emphasis on national security, decisiveness, secrecy, and hints of theology), a bit of Don Messer’s Jubilee (the retro sensibility of his child-care solutions, reopening the debate on same-sex marriage), as well as a reluctant Western populism.

His narrative is tightly controlled; he chooses the story and the way to tell it, and to whom it is told. And what of the narrator? Harper is a putative Westerner, his ideas and adult self formed there, though he doesn’t fit the mould of the Western politician, lacking the polished frontier presence of Peter Lougheed certainly or Don Getty’s rugged athleticism or the extended happy hour of Ralph Klein. No, Harper looks distinctly Central Canadian. He looks like the planned community of Don Mills: meticulous, efficient, and sterile. As a narrator, he is stiff and he has kept to the background, letting the story unfold in carefully presented pictures—his tough-on-crime bill delivered in the company of police officers; his clean-air act presented with mountains as backdrop; a ceremonial Last Spike given to James Pon after awarding compensation to the victims of the Chinese Head Tax. He has kept a tight lid on information coming out of his caucus and limited access to the national press, a relationship still marked by pettiness and an air of regency. His story comes out in Barthesian semiotics, a Western story of stolid morality, the new sheriff riding in to clean up the town.

In 2000, Harper wrote that Alberta and the rest of Canada were embarking on “divergent and potentially hostile paths to defining their country.” Alberta was choosing the “best of Canada’s heritage—a combination of American enterprise and individualism with the British traditions of order and co-operation,” while Canada was “content to become a second-tier socialistic country… led by a second-world strongman.” After Harper lost the 2004 election, elements of the story were toned down to court the soft liberal middle. The anti-abortion elements and attacks on bilingualism were absent. He retooled the Alberta Advantage slogan to Advantage Canada, and the Western narrative was blown up into a national one: Canada, Harper announced, would be the Energy Nation.

So the spectre of Harper was there at the Palais des congrés. The brittle visionary, the controlling, decentralizing, hidden-agenda, End Days, strangle-Kyoto, Reform Harper hung from the ceiling as a Liberal piñata. Interim Liberal leader Bill Graham kicked it off on opening night, directing his geometrical rectitude—the squared body topped by a rectangular head—toward Harper. “I sit in the House, two sword lengths away from the prime minister, and there have been days when, if I had a sword….” Harper, he said, had betrayed history and democracy and those who had invested in income trusts.

Harper had been a surprise, seizing power with the appetite and some of the strategies of Huey Long. Who knew that this blue-eyed, corn-fed Christian child of the suburbs had it in him? He was, if nothing else, finally interesting. In May, a Strategic Counsel poll showed that 55 percent of Quebecers thought Harper was doing a “good job.” Only 6 percent felt he was doing a “poor job.” Through the summer and fall, Quebecers began their habitual drift back toward the Liberals. Still, Montreal was wide open, as the gangsters say.

“If you want to know what Harper is going to do next week,” Scott Brison noted in a practised campaign sound bite, “just look at what George Bush did last week.” If Bush made poor decisions as president, he made a virtue of decisiveness itself and reminded people regularly that at least they knew where he stood. For most of his tenure, this single attribute was seen as more valuable than wisdom, compassion, an ability to negotiate, or even a clear grasp of the issues. He made the tough decisions. This was the spin. That others had made Bush’s decisions wasn’t important; it was the image of a tough-talking Texan that sold them. Harper is the opposite: an ambitious architect and awkward shill.

Harper has two narratives: one is ideological; the other is designed to retain and expand power, to make the Conservatives what the Liberals had been—the natural governing party. The Liberals, who have held power for 80 of the last 110 years, lost seats in 1997 and 2004, and the government in 2006. They are vulnerable. Harper approached the election with the military energy of Sun Tzu (“In the practical art of war, the best thing of all is to take the enemy’s country whole and intact”). He usurped Liberal symbols, and in seducing David Emerson and appointing Liberal MP Wajid Khan as his special adviser on South Asia and the Middle East, Harper co-opted actual Liberals. He offered a few crude gifts, notably the 1-percent cut in the gst, an economically woolly idea, though one with broad, simplistic appeal. Like many politicians, he found a flexible place within the triangle formed by principle, pragmatism, and opportunism. When Harper was granted only a few minutes with the Chinese president, he declared that the cause of human rights had triumphed over the “almighty dollar.”

At the Palais des congrés, there was talk about the conservative id, the Reform heart that still beat below the Conservative surface. But after a year in office, Harper looks, if not entirely comfortable, then at least recognizable: a middle-aged man in khakis and a polo shirt, a little soft around the waist, a bit uncomfortable in groups, a church-going hockey fan. The Liberals are still hoping that Harper’s natural petulance will irk voters, that his fragile alliance will fray, that his evangelical roots will frighten, or that Maurice Vellacott will fall down on the floor of the House of Commons and speak in tongues. But Harper has developed the necessary cynicism to hold onto federal power. Perhaps his decisions have had Shakespearean consequences, the soul tortured by the actions of the man. Maybe Harper has spent nights rereading the Book of Matthew (“For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul? ”) and weeping tears of apostasy. But he is the equal of Jean Chrétien as a street fighter, which makes him dangerous and, on occasion, fascinating.

One of the most critical election issues, one upon which the Conservative and Liberal narratives will clash with the greatest noise, is the fundamental shape of the nation. Trudeau had wanted a strong federal government to prevent the country from becoming “a confederation of shopping centres.” Harper, in turn, described Trudeau’s federalism as “state corporatism” and has begun the process of decentralizing power, granting more money and autonomy to the provinces, re-sketching the lines of Confederation. In a 1994 speech, Harper said, “Whether Canada ends up as one national government or two national governments or several national governments or some other kind of arrangement is, quite frankly, secondary in my opinion.” If as a vote-getter the issue of national unity is the equivalent of a rotting fish sitting in the nation’s sock drawer, for Liberals, it must nevertheless become, once again, the Big Issue.

Arthur Meighen, the articulate, unloved Conservative prime minister after World War I, concluded that Canada’s problem was essentially “spiritual,” the problem of “getting all our people to see that we have not a collection of unrelated sections.” Yet ninety years later, we appear to have a collection of unrelated sections. The Conservative narrative accepts this and lays out a program of efficient administration rather than a binding story. Harper’s five priorities (child care, hospital waiting lists, government accountability, tax relief, and strengthening the justice system) are pragmatic chores, concrete and measurable. His budget priorities are to lower taxes, pay down the debt, and appeal to the nation’s wallet. The Liberals, by contrast, are selling a larger picture, one that is abstract and less measurable. “The great function of political leadership,” Ignatieff said, “is to make people feel that great visceral feeling in your gut that we are a great people.” Dion said, “Above all, we need a Canada more united than ever.” The Liberals engage ancient metaphysical challenges: unity and citizenship. But is there still an audience for the Big Idea? Or is the country content to devolve into regional blocs, and conceivably, in the coming decades, into a handful of city states? The view that Canada is “a community of communities,” as Joe Clark modestly opined, will be tested in the next election. One reason for the Liberals’ dominance in federal politics is the successful marketing of a binding dream, but as the country evolves it isn’t clear that it wants or needs to dream.

A nation, Ignatieff has written, is an imagined community. In the aftermath of the election, Canada will be reimagined in ways it hasn’t been for more than a generation. When Ignatieff declared that Quebec was a nation, it raised the spectre of constitutional talks and sank the hearts of millions. Perhaps it was apathy as much as antipathy that was at play, the threat of climbing back into constitutional waters as appealing as putting on a wet bathing suit on a cold day. Bloc Québécois leader Gilles Duceppe took the opportunity to say that Quebec would be an independent country by 2015.

Harper’s statement that “the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada” (with the qualifier “united” suppling the escape clause the country seems to need) gave him an aura of decisiveness, and launched the familiar semantic parade. A Bloc MP brought three dictionaries—two French, one English—into the House and read out the definitions of “nation” with a discouraging sense of urgency. British Columbia Premier Gordon Campbell argued for nation status for First Nations, and pundits pointed out that the Quebec National Assembly had recognized eleven separate aboriginal groups as “nations,” bringing the provincial total to twelve, with grumpy Montreal Anglos lining up to be thirteenth. A few days after the convention, Ed Stelmach, a former farmer of Ukrainian extraction, now the unlikely premier of Alberta, started muttering about nation status for his province. The country’s narrative, which in recent years has slouched toward the Seinfeldian—if not about nothing, then about free health care, tolerance, and the promise of tax relief—presents fresh challenges.

In Montreal, an anticipated storm front arrived from Alberta, and it was suddenly cold. Amid the detritus of the recent Liberal legacy and Harper’s deft democratic vandalism could be felt the ghost of John A. Macdonald. In 1864, while hammering out the terms of Confederation, Macdonald argued eloquently for a strong central government and was found later that evening drunk in his room, wearing a nightshirt, a rug thrown around his shoulders as he recited Hamlet in front of a mirror. A few years later, he observed the new country’s disarray (as well as his own) and noted, “We are all miserable sinners.”

By Thursday night at the Liberal convention, the delegates had abandoned the soft sell—“Hi, Michael wanted me to ask you if there is anything you want to talk about, any questions you might have”—for a harder line: “Do you want to beat Harper? ” After forty-eight hours of heartfelt platitudes, self-congratulation, and repeated calls for unity, weary delegates retreated to the salons of their respective candidates.

Dion’s party was at the Hotel Place d’Armes, where 150 people had wedged themselves into a meeting room off the lobby. It had the atmosphere of a small-town wedding. Dion had raised the least amount of money among the front-runners, and his campaign was a clever, earnest shoestring operation. There was one free drink per person, and a woman marked every hand with a red felt pen to ensure no one got two. The deal with Kennedy was coming together: the fourth-place finisher would support the third. Dion’s campaign organizer for Ontario said some of Ignatieff’s ex officios were going to Dion after the first ballot. She said the Ignatieff people were drifting. Forty percent of the delegates still hadn’t committed to a second choice. Dion arrived to cheers and announced that their chances were good. “What do you think about that?” he asked, his schoolboy face beaming.

Two blocks away, a crowd of several hundred waited for Ignatieff in the ersatz streetscape of the long, nine-storey atrium of the InterContinental Hotel. This was the hippest-looking crowd, youthful, dressed darkly, laughing brightly, drinking wine as a band played on stage. Ignatieff descended a stone staircase, narrow-shouldered, well-tailored, his natural stoop in check, shaking hands as he moved toward the stage. “What you feel is momentum,” he told his delegates. “What you feel is confidence. And what you feel… is happening. The momentum is with us. But you have a job to do. You have to get out of the tent. Get out. Get out. Don’t stay with the true believers. You’ve got a job to do. You’ve got to go out there and talk to all of them. To those who support Bob. To those who support Stéphane. To those who support Gerard, and you’ve got to persuade them that this is their chance to beat Stephen Harper. C’est nous. C’est nous! You can go to them and say we’re in the same family of faith, the same family of hope, and you can tell them that there is one candidate who can take them over the top!” It was a military speech, delivered by a general who was hampered by a cold and who was aware that his numerical advantage was fragile. Others were massing against him, but on this night he looked like a man of action.

In the bars afterwards the young delegates mingled and tried to dissuade one another from their various positions. They floated through the night on a wave of free drinks, remembered under-graduate rhetoric—“Politics is organized corruption, live with it”—and free condoms. When the morning came, not much had shifted.

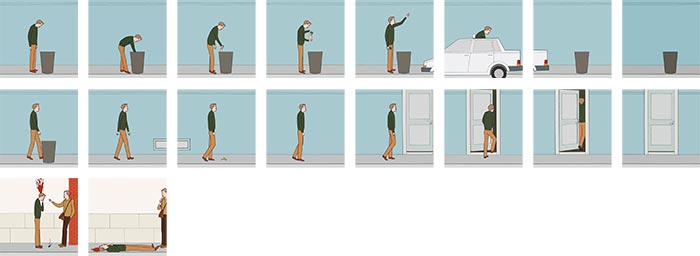

Friday was the first ballot, and Ignatieff ’s people took early control of the north foyer, a thousand strong, their placards pumping, wearing red Ignatieff scarves and T-shirts with Michael’s face repeated in Warholian colour washes. Three hours later the other, smaller armies moved onto the abandoned plain, chanting and marching (“Kennedy, Canada, Kennedy, Canada!”). Scott Brison’s surprisingly large group chanted, “We want Scott!” a cry that was co-opted by Kennedy’s people, who responded, “We want Scott!” Dion’s people took the high ground, marching up the escalators and descending the wide staircase in a continuous circle of red T-shirts. It went on for ninety minutes while they waited for the ballot-room doors to open, a rhythmic pulse where all the chants finally blended and it was difficult to move.

The speeches began, with each candidate retailing his or her vision for the New Liberalism. Had there been Surtitles, as at the opera, that showed the subtext of every speech, they might have shown that Martha Hall Findlay was positioning herself for a run at a federal seat and a possible cabinet post, that Volpe and Dryden had miscalculated, that Kennedy was positioning himself as the next leader, that Rae was offering cabinet positions to Brison and Dion if they came over.

Stéphane Dion began his speech by invoking Laurier and reciting his own commitment to public service, though he knew, as every circuit preacher knows, that God brings them into the tent but the devil is where the money is. Three minutes into his speech, he told the delegates, “Something is wrong… Canada has a prime minister who thinks that the United States is not only our ally, but also our model…. We have a prime minister who thinks that child care is delivered through the mailbox… a prime minister who tore up our climate-change plan.” Dion outlined Harper’s flaws to great applause but was careful not to linger. “To win,” he cautioned, “we must offer our own project to Canadians.”

He outlined his environmental plan and stressed national unity. His delivery was efficient but without drama, and he was cut off before the end of his speech, denied the rousing finish. In Academy Awards style, music swelled, giving him the signal, and he moved to bring it home, but his microphones cut out, and there was that earnest face, with a look of anger and betrayal blown up on the giant screens, his lips moving, the sound of an anonymous orchestra playing.

Seated in front of him was Jean Chrétien, the purest politician the country has produced in three decades, an instinctive fighter who had delivered three majorities and who looked, in the unflattering, changeable light of the convention room, darkly reptilian, his limbic self revealed as he watched his creation onstage. He had plucked Dion from academia to use him as an attack dog for unity. Dion was not a natural politician, and ten years later he still isn’t. He is the antithesis of Chrétien, a shy, rigorous thinker. A reporter asked Chrétien what a good leader was. “A good leader,” answered the pragmatist, “is one who wins elections.”

Bob Rae was the closest to Chrétien in terms of presenting a purely political campaign. His most thorough policy document had only arrived that day, the first concrete glimpse of what he would do after eight months of campaigning. He eschewed the lectern and wandered the stage with a hand-held microphone, a life coach telling us of his troubles and how he overcame them. Liberal ideas were easy to find, he told us; his colleagues had good ideas, there were ideas on the Internet, the Google Liberalism approach. What was needed was a politician, an experienced leader who could implement them. He was politics.

After Rae came Ignatieff ’s patrician speech, polished, safe though with a bit of fire, the most prime ministerial, and, in the homely hearts of the assembled, the most presumptuous. He was a divisive force in a still-divided party and he tried to bring everyone together tonight. “Tous ensemble!” he repeated. “Tous ensemble!” He outlined his Canada and its specific greatness. Ken Dryden had already given the crowd the grassroots Canada that he had seen while driving across the country, staying in people’s guest rooms, and visiting folk festivals and methadone clinics. Scott Brison sketched the Canada of Big Dreams, Dion the country as environmental world leader. Everywhere there was a sense of scope and grandeur. In a Maclean’s article a month earlier, Ignatieff had described Canadians as “less than the sum of our parts,” perhaps the fairest assessment, but not one for this night.

On Canada Day, as the Liberal leadership candidates were flipping hamburgers and smiling wilfully at picnics and barbecues across the country, I was standing with sixty or so people in the shallow water of Mary Lake, north of Toronto. Lumpy and pale, we stood with our children and their inflatable toys, squinting across the water. There was a microphone set up on the dock beside the public beach, and a local politician said a few words about the greatness of the nation and then introduced federal Health Minister Tony Clement, who owns a cottage nearby. Clement was on a swing through Muskoka that day, spreading good cheer, and this was his first stop. He reiterated our greatness to a few cheers and then walked among us, handing out small flags. I doubt that a dozen people recognized him. He went back to the microphone and said goodbye and waved. “Thanks for the 1 percent!” a sunburned man yelled, clutching his flag.

Canada is more easily defined in literary than political terms, an act of faith and imagination that is separated by familiar forces (language, geography, ethnicity) and bound by tolerance. The few sustaining mythologies are diluted through successive generations and through the general lack of interest from immigrants. The Dominion Institute, founded in 1997 to address “the erosion of a common memory and civic identity in Canada,” provides disheartening statistics on how little knowledge is shared. Only 5 percent of Canadians surveyed could name the 1873 Pacific Scandal as the event that brought down Macdonald’s first government, and more than a quarter identified US general Douglas MacArthur as a Canadian war hero. Do we know who we are? Is the country a collection of short stories or is it an epic novel?

“As a cultural ideal,” Ignatieff wrote in Blood and Belonging, “nationalism is the claim that while men and women have many identities, it is the nation that provides them with their primary form of belonging.” Oddly, non-white immigrants arrive in Canada with a greater sense of belonging than whites, but that sense diminishes in the second generation, while the white immigrant’s sense of attachment increases. This suggests that multiculturalism remains more successful as an idea than a reality. A recent poll showed that second-generation immigrants felt less attached to Canada than their parents do.

There is an innate need to belong, to attach oneself to something. The global consumerism that optimists felt would eventually displace nationalism—an idea that reached its apogee in Thomas Friedman’s Golden Arches theory that no two countries with a McDonald’s had ever gone to war—has proved incorrect. Tribalism isn’t easily supplanted by common economic interests, and it remains a stubborn, visceral force.

In 1968 Trudeau wrote, “By a historical accident, Canada has found itself approximately seventy-five years ahead of the rest of the world in the formation of a multi-national state and I happen to believe that the hope of mankind lies in multinationalism.” Though multinationalism, like globalization, can erode national identity, Canada is staring at the middle game of pluralism. And what is the endgame? There is a danger that the combination of regional alienation and the lack of attachment that immigrants feel will turn the country into a vast abstraction, a cross between a larger, less lucrative version of Hong Kong and John Lennon’s “Imagine,” a postmodern experiment rather than the world’s most successful multinational state.

The idea of national greatness is a common political theme, whether it’s Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, Mao’s Great Leap Forward, or Bush’s tenuous empire. Canada’s greatness lies in its potential—as an exemplar of a working multinational state; as an enviable, global model of diversity; and, more pragmatically, as the owner of increasingly coveted resources. The country continues to stumble toward greatness, aided by the relative failure of other nations to deal with multinationalism.

All societies have fears about breaking down because all societies eventually do break down. What kills them, ultimately, is a lack of meaning. The search for meaning has been long and hard-won, and it isn’t encouraging that 140 years into official nationhood, a Member of Parliament is reading aloud the definition of “nation” in both official languages with a sense of genuine purpose. With a sovereigntist party in the House of Commons, Canada is faced, daily, with the means to its end.

The civic nationalism that is Canada’s—bound by laws and shared rights rather than ethnicity—nevertheless has themes that resonate through much of the population. According to recent figures from the David Suzuki Foundation, 90 percent of Canadians said, “It is very important for national identity that Canada be a leader on world environmental issues.” There is the perception among Canadians that the country is an environmental leader, yet in a ranking of thirty industrialized nations Canada sat twenty-eighth, ahead of only Belgium and the United States. Other rankings are equally dismal. In terms of per-capita carbon dioxide emissions, Canada produces 19.05 tonnes per year, compared with France’s 6.8 and the UK’s 9.5. Along with the US and Australia, Canada is the environmental equivalent of a soccer thug. Its 33 million people consume as much energy as the continent of Africa with its 900 million. “You think of yourselves as a liberal and enlightened people,” scolded British writer George Monbiot in his book Heat: How to Stop the Planet Burning, “but you could scarcely do more to destroy the biosphere if you tried.”

Last spring and winter were the warmest since Environment Canada began tracking mean annual temperatures. Nonetheless, Harper has cancelled Kyoto Protocol initiatives and cut funding to climate-change programs by 80 percent. Alberta, Harper’s political base, is the country’s largest producer of hydrocarbons, and the oil sands are one of the most concentrated sources of global pollution. It was left to Environment Minister Rona Ambrose to explain the government’s isolationist position, and she stayed on message with the tenacity of the early Ronald Reagan; she was vilified by the left for incompetence and by the Liberals for idiocy. In the House, and in tentative trips abroad, she had an air of the sacrificial, like the first to go in a horror film.

The environmental policy outlined by Dion addressed the country’s perception of itself as an environmental leader (“Canada on the podium of the sustainable economy”), while Harper, with his attenuated and cleverly named Clean Air Act, went with what Canada is: the Energy Nation.

It was the second ballot that would tell where the movement would start. The delegates walked in tight circles and talked on their cellphones. They worked on the enemy, pointing out glaring weaknesses—character, electability, language—questioning whether they were truly Liberals.

Finally the results: Ignatieff up little more than two percentage points, a disappointment; Rae up four points, Dion narrowly ahead of Kennedy. Then Kennedy went to Dion, a surprise. He could have stayed for the third ballot and perhaps edged Dion out, but suddenly it was a three-way race with a new set of unanticipated equations.

When Rae got bumped off the next ballot there was a dark rumour that he would declare for Ignatieff, that the months of polite hostilities between the two would be forgiven, that the old roommates would unite. This unlikely but dramatically tantalizing scenario hovered for fifteen minutes, as the cameras followed Rae’s movements through the crowd. Would he go to Ignatieff or to Dion? In the end, he sat down beside a man in a turban and chatted comfortably, as if he were at a cocktail party, a man of words. It was down to Ignatieff’s smooth, forceful Liberalism and Dion’s green tutorial.

Toronto MP John Godfrey walked by, declaring for Dion. “The environment,” he said, shrugging. Former Ontario premier David Peterson, who had backed Ignatieff, stared at the wreckage of the third ballot. “We’ve lost,” he said.

What happened in the heads of the delegates who chose the leader on the final ballot? Was it momentum? The environment? A backlash among the delegates who couldn’t recognize themselves in Ignatieff? He had raised Quebec and Israel, two topics that divided opinion, good news for an intellectual, but less so for a politician. Perhaps he should have stayed with his original statements, not waffled. Now he looked, once more, like a man of words. The camera stayed on him, searching for cracks in his facade while waiting for prime time before announcing the results, which were foregone. Dion was unglamorous but familiar. There were a hundred men at the Palais who looked like him, wearing practical shoes and glasses and warm fleece vests. The delegates—veterans of 1968, the retired, the young, the ideologues, the single-issue bores, religious lobbyists, groupies, and academics—herded toward Dion.

After the last ballot but before any announcement, Jean Chrétien addressed the crowd. To watch Chrétien is to see the essence of Liberalism, that mixture of voodoo and instinct and machinery that carried them for more than a decade. Consider his gifts: linguistically eclectic, intellectually indifferent, politically astute, a mixture of the sinister and the avuncular. Yet when he spoke, he roused his people. “Harper was watching earlier. Maybe he is still watching. Stephen, Stephen—can I call you Steve, like George W.? ” His appeal is difficult to define. Perhaps voters accepted his sweet, fraudulent mythology, le p’tit gar de Shawinigan, or maybe it was the grudging respect accorded survivors. Or the unknowable alchemy that is the successful politician.

Ignatieff was gracious in defeat and Dion conciliatory, if uninspiring, in victory. Renewal had been one of the great buzzwords of the convention, a buzzword at every convention, where the contrary notions of change and tradition are trumpeted in arbitrary rhetoric. In the end, a Liberal compromise: both change and renewal in the form of a ten-year veteran of the government, but one who wasn’t associated with the establishment. The old order, the remnants of the machines that had delivered Chrétien and Martin, and the machines that had wanted to deliver Ignatieff or Rae were effectively gone. Dion came in with few obligations, the people’s choice.

Who else was at the convention? The ndp were there, Olivia Chow circulating, sociable and elegant. The Conservatives were there, observing and distributing buttons, one of which read “Go for Bob—Go for Broke,” a reference to Rae’s economic record as premier of Ontario, an uncharacteristic flash of wit. Notably absent were the Americans, weary veterans of federal politics, Margaret Dumont to Canada’s Marx Brothers, who have attended past conventions as a cultural threat, occasionally as a military entity, and always as the economic bully waiting outside in the parking lot. Macdonald had had to deal with them on the issue of protective tariffs in the 1878 election. Laurier was still dealing with free trade in the 1911 election and lost because of his support of it (unwisely characterizing it as a “commercial union”). Free trade has polarized Liberals and Conservatives since Confederation, with each party periodically changing sides. Even Mulroney, the modern champion, was against it as late as 1983. In 1957, Diefenbaker thundered that Canada was in danger of becoming “a virtual forty-ninth economic state in the American union.” Dief was elected, in part, because of the anti-American sentiment in the country, but once in power he quickly signed the North American Air Defense agreement, putting the country’s air security under joint Canadian-American control and offending the electorate. After being elected, Harper expanded norad’s role, though without the protest that Dief encountered. There has been a fundamental shift in the anti-American narrative. There is periodic protest, but it is muted.

The turning point was shown on the big screens of the Palais, the 1988 showdown where Liberal leader John Turner told Brian Mulroney that the Free Trade Agreement would reduce Canada to an American colony, and that once the economic levers were ceded, the political levers would follow. The electorate didn’t agree, or it didn’t care. Since then, and especially since 9/11, ties with the US have accelerated dramatically and include energy, security, the sharing of intelligence, regulatory harmonization, and commercial alliances. This increasingly deep integration hasn’t come about in big, debated gestures like nafta, but in smaller, less-publicized ways. The political covenant that has been in effect since the first elections in Upper Canada—protect us from the US—has largely dissolved.

The genial menace of America was replaced in Montreal by Howard Dean, former governor of Vermont and presidential hopeful, celebrated screamer, and now chairman of the Democratic National Committee, who delivered a keynote speech in which he told delegates that the Democrats and the Liberals shared principles and values. They also share a sense of purposelessness of late, and both are searching for a galvanizing idea. Dean spoke a little French to great applause.

Last year was one of record sales of Canadian companies: in the second quarter of 2006 alone, there were 480 deals worth a total of $86.1 billion. Some of this is the natural result of freer global trade and it is offset by the purchase of foreign companies by Canadian firms. But 2006 also saw the sale of iconic Canadian companies (Hudson’s Bay Company, Molson) and other significant names (Domtar, Dofasco, Vincor, Fairmont Hotels & Resorts, and Intrawest, owner of Whistler Blackcomb, site of the 2010 Olympic Winter Games), all of which passed with little comment.

The softwood deal gives Washington unprecedented control over Canada’s lumber industry and revealed the weakness of nafta, its impotence in the face of American will. Roughly half of Alberta’s oil industry is controlled by American interests, and under the terms of the Free Trade Agreement 60 percent of Canadian oil and gas has to be exported to the US, even in times of domestic shortages. It isn’t clear if water is covered by the Free Trade Agreement. Not since the seventeenth century have Canada’s resources been so coveted. Once more the world is coming to our shores, looking to get fat.

The political approach to this has been bifurcated: the private acknowledgement that there isn’t enough investment capital in the country to develop its resources, and that there is a net economic benefit to foreign investment/ownership, is combined with a sense of righteous indignation at election time. While foreign investment creates jobs, the best jobs—research and development, planning—are reserved for the head offices. At its growing number of branch plants, Canada supplies only labour and middle management. And there is the environmental impact of industry; the locals, as is so often the case in the Third World, are left to clean up the mess. There is less public concern now about the implications of foreign ownership, about continentalism, and closer ties to the US, and less need for manufactured government outrage. Whether this is due to a maturing of economic thinking or is the result of collective ennui isn’t clear. Perhaps novelist Yann Martel is right: Canada is essentially a hotel.

A week before the convention Stephen Harper became the unlikely protector of economic sovereignty, announcing a pending bill to limit foreign investment when it isn’t in the “national interest.” Finance Minister Jim Flaherty clarified: “For example, foreign investment by large, state-owned enterprises with non-commercial objectives and unclear corporate governance and reporting may not be beneficial to Canadians” (though the list of Canadian companies with unclear corporate governance and reporting is a long one). The policy was aimed squarely at China, though it had already been shut out of a deal to buy Noranda, and Falconbridge and Inco had recently been sold to Brazilian and Swiss companies respectively, leaving less to buy in the mining sector. The Chinese had also, surprisingly, pulled back from Alberta oil-sands negotiations (while retaining investments by Sinopec Group and China National Offshore Oil Corporation) and taken their business to Iran in the form of a $100-billion oil deal.

The Conservative announcement had little practical effect but held some political value. It curried favour with the US, which views China’s presence in the oil sands as a security issue, and Harper’s timing was exquisite. He ran a campaign alongside the leadership race, stealing pieces of the Liberals’ traditional agenda—human rights, raising the flag about foreign ownership, even multiculturalism—while offering recognizable Tory gifts such as less tax, less debt, less government.

After Dion’s victory speech, delegates headed toward the exits of the Palais, dehydrated and hungry, relieved and confused. They weren’t leaving with their fists pumping, war cries ringing through the halls, thirsty for Tory blood. Perhaps there was already a slight twinge, a feeling they had made a strategic mistake, that they had voted their conscience rather than for victory. Was this the champion to slay the beast? Dion was unloved in Quebec and a hard sell in the West. As we lined up for takeout sushi in the bowels of the Palais, the cashier warned the assembled: “You have taken a big risk. A very big risk. Dion can’t win in Quebec. Jamais.”

In preparing for the election the two sides have begun to claw their way toward the middle. Forty years ago, Trudeau wrote that the main distinction between the conservative and the progressive is that “the progressive will tend to overestimate the people’s desire for justice, freedom and change, whereas the conservative will tend to err on the side of order, authority and continuity.” At the moment, the electorate appears to have a limited appetite for freedom or order (which it feels are reasonably assured) but it is ravenous for change and authority.

There is a Through the Looking Glass aspect to federal politics that goes something like this: The ndp borrows the occasional idea from the Green Party, but feels it is a marginal group (ndp Pat Martin said the Greens functioned primarily as “a big catch basin for wing nuts who would otherwise gravitate to our party”). The Liberals poach ideas from the ndp (former ndp head David Lewis was called the best policy chairman the Liberals ever had) and feel, in the words of Martha Hall Findlay, that they “have good ideas but are unable to implement them—just ask Bob [Rae].” The Conservatives have contempt for the Liberals, but strategically Harper can be a Liberal himself—his chemicals-management plan, built on a Liberal initiative, has the added benefit of stealing back the environment from Dion.

Canada isn’t the only country where the definitions of liberalism and conservatism are being refined, colliding in a slow-motion car crash. In Spain, the Socialist Party introduced radical social legislation but also embraced free-market economics and lowered income taxes by 6 percent. In Britain, Tony Blair used a combination of fiscal conservatism and Labour rhetoric to hold onto power for a decade, and now British Conservatives, who have learned from Blair, are championing bicycle paths and the environment. In the US, Bill Clinton was described as the best Republican president since Eisenhower. The Liberals have long been accused of campaigning from the left and governing from the right, and traditional lines continue to blur in the rush for the centre. The ndp is “tough on crime,” the Conservatives celebrate diversity, Ignatieff favours Canada’s continued military presence in Afghanistan.

The Liberals have Laurier and Mackenzie King and Chrétien as models for finding and holding the middle ground, while Harper has Mulroney and Diefenbaker. Mulroney’s massive majority is tainted by his scorched-earth legacy: leaving two seats and years of chaos. Diefenbaker trounced Lester Pearson but was undone by his inability to carry Quebec (in a moment of Shakespearean drama, Dief ’s political death was initiated by his then-protegé, Brian Mulroney). If Harper fails in the election, his model could be Arthur Meighen, a bright, arrogant man who was prime minister from 1920 to 1921, and then again for a few months in 1926, a leader who couldn’t have found the middle ground if it was nailed to his head. If Harper is successful, however, his energies will go toward securing that middle ground, then to testing its rightward borders, to make Liberalism irrelevant.

In the House on the Monday after the convention, the two Steves faced off, policy wonks, both a bit rigid, unhappy in crowds, but with each other happily combative. The Liberals tore into Harper’s Clean Air Act, and the Conservatives savaged Dion’s environmental record. In the new narrative, Harper will try to convince voters that Dion will deliver a green, expensive, and paralyzed Canada. Dion will try to convince them that under Harper Canada will become a version of Bush’s America, with its quietly eroding rights, its lack of government transparency, and its belief that poverty is God’s judgment.

In 1983, Gore Vidal, no fan of Richard Nixon, wrote, “We are Nixon; he is us.” The same may be true of Harper. He is awkward, shy, conniving, the physical embodiment of the suburban middle class. That he is using Alberta as a model, a wonderful, largely vision-free province that has recently been governed by the principles of a drunken lottery winner, isn’t necessarily cause for celebration. Dion is the new face of Liberalism; bespectacled, shy, with more steel than is first suspected. Harper will govern the country as he sees it: a colony to be efficiently administered. Dion will govern it as it exists in the Liberal imagination.