In 2004, Atif Rafay was sentenced to three consecutive life terms for the brutal 1994 murders of his parents and sister in Bellevue, Washington. Lacking physical evidence, the local police worked with the RCMP to obtain a confession in British Columbia from Rafay’s best friend and alleged co-conspirator. To get it, Canadian officers used the controversial “Mr. Big” scenario—illegal in the United States, where it is considered a form of entrapment—in which undercover agents pose as high-level crooks, then prompt a target to describe his involvement in a past crime as a way of gaining trust.

Rafay was an eighteen-year-old arts student at Cornell University at the time of the murders. He has always maintained his innocence.

This intense conviction of the existence of the self apart from culture is, as culture well knows, its noblest and most generous achievement.

Lionel Trilling

Once upon a time, I saw a documentary featuring black and white footage of Glenn Gould, shot soon after his first recording of The Goldberg Variations, in which he had taken such extraordinary liberties—excessive liberties, some thought—with Bach. Although by then in his mid-twenties, the pianist gave the impression of being still almost a boy, still very much the prodigy. Seated outdoors, he answered his interviewer reluctantly, as if unused to conversation. Shifting around in the chair awkwardly, as if also unaccustomed to furniture, he spoke in quick runs, punctuated with abrupt halts. But gradually enthusiasm overcame diffidence. As he warmed to his theme, he became himself: voluble, playful, precise. The nimble fingers danced his ideas for the camera; the face radiated happiness and confidence. “I’ve often thought that I would like to try my hand at being a prisoner,” he said later in the film. “I’ve never understood the preoccupation with freedom as it is reckoned in the Western world… to be incarcerated would be the perfect test of one’s inner mobility.”

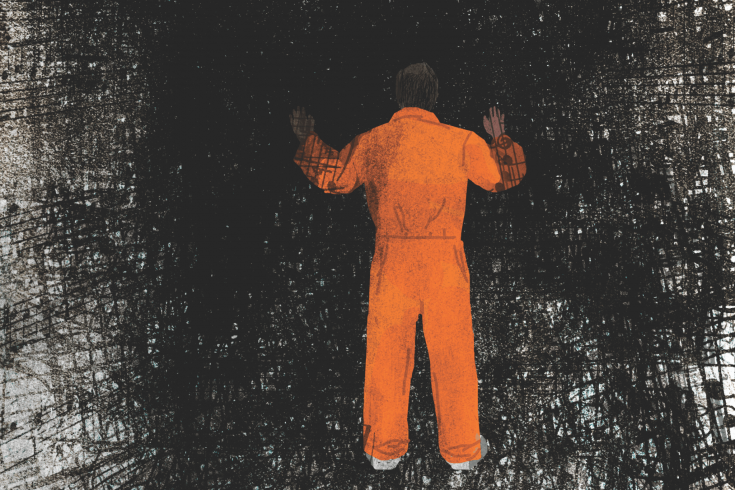

I had known Gould’s recordings and writings for more than a decade when I heard this declaration, but though I had been incarcerated for just as long I didn’t think I understood freedom. I felt, rather, that prison had left me bereft. If I had been changed, it was not for the better.

Perhaps Gould’s remarks were offhand, no more than callow bravado from a private genius. I should have liked to ask him what he intended with the phrase “inner mobility,” and I wonder whether he ever came to feel that he understood freedom. What remains vivid in my memory is his powerful sense of something as yet undisclosed to him of freedom, of something elusive but nevertheless essential to attain. His words reach at it. They are properly philosophical. They make a problem of freedom, so often taken for granted; and perhaps philosophy has no higher calling than to make us aware of what we take for granted, by drawing our attention to this something problematic about life that may constitute its very meaning.

I have been a prisoner almost half my life, more than long enough to know that what finds voice in Gould’s words—more than a sentiment, less than an idea—is fairy tale. Is my interest a symptom of the wish to be convinced that incarceration (to the ordinary world an object of revulsion and derision, of horror and contempt) might possess some special worth? That kind of wishful thinking happens all the time in prison, and everyone usually encourages it. Sufferers wish to be reassured that they have had more from their suffering than damage, and so prisoners addle themselves with the hope that their prisons may do more for them than ruin their lives and limit their understanding. Naturally, the world at large finds this entirely endearing: such hope obviates any need to make the expectation plausible. Though I otherwise scoff at the substance of things hoped for, do I fasten to Gould’s valorization of incarceration with the self-serving fervour with which the poor and meek might cling to Christ’s blandishments? If I do not imagine inheriting heaven or earth, am I nevertheless flattered to think that I have tested inner mobility, and understood freedom?

I hope not. Even if I thought prison could deliver such understandings, I would have to count it among the sadder bargains imaginable. There are no colder comforts than knowing precisely all that one has missed and that is forever irrecoverable. But I do not harbour even these illusions about what actual incarceration brings; nor can I pretend it offers any illuminations that are not benighted. The proper attitude toward real prisons, these disgustingly efficient contraptions for turning men into ghosts, is the one Conrad’s narrator strikes in Chance. Marlow does not ever think to try his hand at prison. It is rather a thing that leaves him sick: “sick and scared.”

I do wish I could have an improper attitude. I wish I could talk of trying my hand at prison as if it were an especially enchanting pianoforte; I wish I could belong to the world that can. But I am not so free. I can never think of prison without being sick and scared.

Gould’s words interest me not despite their fairy tale quality, but precisely because of it—because they evoke a fairy tale I loved long before I knew of prisons, and love still, even in dismal rooms and worn-out clothing, after dumb drudgery and cold nights, through solitude and disappointment. I have always loved fairy tales, those of the brothers Grimm and those grimmer than any they told, and the fairy tale that underlies what Gould said that day is perhaps the greatest of them all: the loveliest, and the grimmest.

Its scheme is simple. There was once a soul in bliss. But bliss was lost, and the soul went unrecognized, even to itself. Only in and through tribulation and sorrow, on the wheel of fire at the summit of human experience, was the soul again acknowledged and recovered. The fairy tale tells us that we cannot grasp what we have until it has been lost, that only pain discovers the soul in its perfection. Only through suffering can human beings reach their ultimate potential; only by agony do they become who they are. Though I call it a fairy tale, the narrative forever verges on tragic myth: against the cliff Prometheus is bound and unbound, again and again.

The premise of this fairy tale is the idea of the durable spirit, that old and cherished faith in the indestructibility of the human soul. This belief was powerful enough to ensure that the medieval familiarity with the effects of torture is not discernible in the age’s representations of hell, in which the victims are imagined to remain lucid. As Erich Auerbach so movingly observes in Mimesis, the denizens of Dante’s Inferno are not consumed by their ghastly punishments, but become more fully the individuals they are and have been on earth. Their essential character can only be brought into ever-higher relief; eternal judgment perfects it. Though each soul is given being by God, its individuality belongs to itself and is inalterable in essence. These unique souls and their inevitable destinies, which are only figured here on earth, are fulfilled in the afterlife. In such a conception of self, only that which remains constant through carnage counts as real: the soul’s mobility is the true measure of its authenticity. So it was that the Inquisition’s torturers never feared to destroy those they tormented, for what mattered in their victims was beyond all destruction. God sends souls to suffering and damnation forever, but he thereby preserves them in their human uniqueness forever. They also serve who only stand and burn. And by its very irrevocability and the infinity of its torture, the prison of the Inferno becomes a setting against which the humanity of the damned stands out with a glory that eclipses mere divinity.

It took the Enlightenment to make this formidable story finally incredible, to recognize that human beings are not given to themselves at the moment of their conception nor on the day of their birth, but must be continually made to be: to acknowledge that the process is a construction and not a revelation. Man is not, as Rousseau thought, “born free”; a world is needed to liberate the human spirit. In one way, the idea was far from new. Epictetus had taught it emphatically: “Only the educated are free.” But it had been set aside in the era when Augustine could write of the “disease of curiosity,” and Lactantius could ask what blessing could be had from learning the source of the Nile or “some mad theory about the sky.”

Only with the renascence of science did humanity begin to be consciously seen once again as something not natural, but artificial: now a product of society and tradition, an existential creation rather than a mystical essence. Not for nothing does Hans-Georg Gadamer call Bildung—the formation of the self and the attainment of humanity through culture—“perhaps the greatest idea of the eighteenth century.” The consciousness of freedom is acknowledged to be not immanent, but something that develops; for Hegel, its progress is the history of the world. What had been regarded previously as no more than the refinement of inborn traits is reimagined in this tradition as becoming human, as acquiring an ungiven self through work upon the self: everything that may be subsumed under the rubric of liberal education, education that makes free human beings, liberi.

Liberty thus acquires a new, radical sense: no longer is it merely licence, or the gratification of essential inner impulses. No longer is it just absence of constraint. Instead, nature itself is seen as potentially a fetter, and autonomy becomes a special power of the human summoned forth by culture for the realization of authentic freedom. The man of reason is free precisely insofar as he has become sovereign over himself. Having internalized the demands of tradition, and having disciplined himself to maintain control over the dictates of appetite and impulse, the cultured human being is conceived as having both emancipated and mastered himself by the labours of learning, which prove to be the very toils of freedom.

It is only fitting in this context that “toil” should mean “snare” as well as “work,” for it will readily be admitted that this process of becoming free is quite the opposite of freedom as animals—or savages—might understand it; or our contemporaries, for everything is done to deny the toil of culture necessary to make human beings free in the authentic, modern sense, the one founded in autonomy. So we reach the idea of prison as a test of the spirit, as in days past earthly life was only a test, and perhaps one of the reasons many Americans do not shrink from inflicting life sentences in prison is that so many of the religious imagine the earth to be merely a prison anyway. It is as an irony that we should understand the concurrence of the modern prison’s emergence with the Enlightenment’s new consciousness of freedom.

Gould would not have been thinking of this history on that day. For him, prison was an abstraction; he was thinking of his music, the purest of delights, the greatest, the most humanizing. He was imagining solitude and piano, scores and recording equipment, a more perfect communion with that hereafter he reached only in ecstasis: he was conceiving of his life simplified to the essential activity of his being.

The thought of suffering seems not to have entered into his understanding of prison. It was for him more an emblem of forcible restriction, and therefore of concentration and intensification, under which the truth of freedom might emerge. This idea of prison has not wanted for distinguished proponents. Nietzsche wrote, “The highest type of free man should be sought where the highest resistance is constantly overcome: five steps from tyranny, close to the threshold of the danger of servitude.” Before he was incarcerated, Oscar Wilde, ten years Nietzsche’s junior, had written, “After all, even in prison a man can be quite free. His soul can be free. His personality can be untroubled. He can be at peace.” He would reach a different conclusion once there.

The thought of suffering would not have created a serious objection for either of them. The aspirational ethic that unites their thinking wilfully embraces pain. The abiding theme of the great tragic fairy tales Wilde wrote is the transcendental value of agony, on the model of the Passion of Christ. It was, indeed, from Wilde that I first learned the special poignance of the meaning of suffering, listening to my mother read from The Happy Prince and Other Tales and A House of Pomegranates—though I want to assert that it must have spoken to something inside me already, just as I want to imagine it speaks to what is human in us always.

A romantic notion, at once glorious and seductive: perhaps what truly matters in us is proven in a crucible; what we ought to become can only be attained in extremis. No one emphasized the idea so much, or so eloquently, as Nietzsche did:

To those human beings in whom I have a stake, I wish suffering, being forsaken, sickness, maltreatment, humiliation—I wish that they should not remain unfamiliar with profound self-contempt, the torture of self-mistrust, and the misery of the vanquished: I have no pity for them because I wish them the only thing which can prove today whether one is worth anything or not—that one endures.

And again: “Only great pain is the ultimate liberator of the spirit… that long, slow pain in which we are burned with green wood, as it were—pain which takes its time.” Nietzsche and Wilde received what they asked for, so far as pain and misery are concerned—not more, though it may seem so, for the excess is essential to agony. Only that which goes beyond what can be imagined or thought bearable, that which continues when it is no longer endurable, constitutes the true passion of suffering.

So in De Profundis—the long, agonized letter he wrote from his cell in Reading Gaol between January and March 1897, ostensibly to Lord Alfred Douglas—Wilde says that suffering is not a mystery but a revelation, in which what “one had felt dimly through instinct, about art, is intellectually and emotionally realized with perfect clearness of vision and absolute intensity of apprehension.” He claims that “sorrow, being the supreme emotion of which man is capable, is at once the type and test of all great art.” What he does not write is that when he had initially been allowed nothing to read or to write with in Reading, there had been no exaltations: only broken pleas to the warders for books and pen and paper, and warnings of approaching insanity. What he could not have known is that after De Profundis was finished, he would come out of prison a broken man and die three and a half years later, never having written more than mere earnests of anything of importance again. Nietzsche, for his part, had already collapsed in tears in Turin in 1889, never regaining lucidity. Both died in 1900: Nietzsche at the end of August and Wilde at the end of November.

In our time, some chide Nietzsche for taking things too personally and too seriously: William H. Gass supposes in Harper’s that Nietzsche’s final books evince his “frayed mind,” and that his amor fati is “acceptance driven like a truck toward a checkpoint.” For others, Wilde’s death seems something of a relief: “Anyone who has read through De Profundis… would not wish for more from his pen,” opines G. W. Bowersock in The New York Review of Books. I, for one, cannot find it within me to presume that they knew not what they had won with their long agonies. Devoted without sanctimony—with irony, levity, and wit instead—to their individual ends, they intimate a world apart from the sphere of their sorrow; and their wretched and desolate ends stand not as refutations, but as the aptest measure of the value of what they sought.

One should not be too hard on the comfortable, though they tend to be hard on the uncomfortable. They have, perhaps, simply no eyes for what the latter seek to disclose. This above all may make sufferers reticent: the conviction that theirs is a world of experience that others cannot know, nor imagine by any act of will. Even Dostoevsky, so skilled in depths of anguish, slipped. In the course of the serialized novel derived from his time in prison, keenly entitled The House of the Dead, he described, with incredulous indignation, the heedless good humour and cheerful mien of a young parricide who had been in prison a decade. Dostoevsky based his account upon an actual prisoner whom he had come to know. When he received word, before the novel was finished, that the man whom he had characterized in scathing terms in the book had in fact been innocent, he found himself, for once, at a loss for words; he found that he could write nothing to enlarge upon such a thing. The fact, he wrote, was too enormous; it spoke for itself.

Nietzsche, I think, would have recognized what Dostoevsky had failed to notice: a “certain ostentatious courage of taste which takes suffering casually and resists everything sad and profound.” I have personal reasons for finding this minor episode of literary history moving: it resembles my own. Still, pain isn’t strictly proportional to enormity of injustice. To be more sinned against than sinning is likely, on balance, a relief. But self-recrimination is misery for the innocent and the guilty alike; regret is stubborn salt to wounds, even without the hangman’s metaphysics, in Nietzsche’s words, of free will. A friend of mine, before his own suicide, once wished me to die swiftly, and I have no doubt, none whatsoever, of his goodwill.

The world no longer believes in suffering, in the pathos of numinous meaning. That tremendous haut relief of tragic illumination, which even at a remove calls out for mountains or at least stone fit for monument, has no place in the market economy or the bureaucracy of the modern state. The ecstasy of agony is now clichéd: everyone has heard—though not from Nietzsche, surely—that what does not kill them makes them stronger, and “No pain, no gain” is the mantra of fitness buffs and corporate raiders alike. But we know the lessons of psychology. Harlow’s monkeys rarely recover from their deprivations; they bury their heads and scream and scream. So much that is precious is also fragile, and only ashes emerge from some crucibles.

We are no doubt better off without the prisons that tamed Wilde. But something may be said for the dignity of tragedy once granted to sufferers by the conviction that suffering discloses something worth more than the entire ordinary world. There is another kind of suffering in the prisons of today, quite different from the agony of which Wilde made such profound use. The romance that could survive in Reading Gaol fares ill in the prefabricated architecture of the modern prison. These concrete and razor wire prisons are in their own way less kind than even the bricks of Reading Gaol. Gould could have tried to content himself by humming Bach partitas, but he would have found it difficult through the thumps and screeches of death metal or rap, through yelling and heinous laughter and television. Instead of desolate affliction openly acknowledged and torture murderously inflicted, the better prisons of today put up an ugly parody of life. Under the inhuman rubric of “corrections” and in the robotic “positive programming” jargon of today, the prisoner is enlisted in gainless employment, in banality and triviality, in the perpetual effort at a modicum of physical comfort. Here there is no crucifixion, but endless Stations of the Way: the steps that must be willingly taken, the knowledge that each volitional step is a movement toward a dismal and mean end. As torturers know all too well, the victim’s feeling of complicity with the pain makes the suffering greater. So it is that the knowledge of my own collaboration in the days of my ordinary prison life, in the rituals repeated and the trifling pursuit of utter inconsequence, makes the awful nullity of the existence worse. Longing, futility, repetition: how uncanny the Greeks were in their psychology of suffering when they imagined the punishments of Sisyphus and Tantalus.

The overcrowded prisons of today immerse the prisoner in a foul-mouthed world pervaded by an underlying bestiality of spirit, a world without ordinary freedom and with no sense of any other. Hell is other people, Sartre reported; prison is filled with them. The person forced into prison is plunged into the strife of pompous thugs with corrupt images and inane slogans inscribed on their bodies like graffiti on the dirty wall of a dilapidated lavatory. The stereotype of prisoners as monstrous, grotesque predators tells much more about the mentality of the public than about the reality of the prisoners, but that phantasmagoric image is still closer to epitome than to caricature of the prison subculture itself, which is a toxic distillation of the degraded mass culture from which it springs.

Perversely, it is for the worst that prison is hardly a punishment. These inmates are in their element. Actual violence is honoured. Savagery secures a conscious respect. The coarsest racial tribalism, fundamentalist religion, misogyny, philistinism, junk food, the kitsch cult of sports: all dominate in a hermetic environment that works to make it all seem perfectly natural, as though to induce prisoners and guards alike to forget that anything else exists, could exist, or has ever existed on earth. Nothing remains uncorrupted: Christianity, which once served to chisel out refined human beings, here churns out the crude and the coarse. What inspired Fear and Trembling and Bach is reduced to hokum, bestsellers, and banjo music—if not far worse.

Individual prisoners, of course, may not conform to any of this, but the contagion of prison air is irresistible; even resilient individuals acknowledge its hegemony. And so any life must be a conscientious struggle, an existence of inner exile and alienation, with pantomimes of feigned interest, suppressions of boredom, and expressions of profane pieties. Everything that demands careful development—sensitivity, tact, discernment, incisiveness—dulls in desuetude in prison. Such oddities as curiosity, subtlety, grace, and intelligence, which have little enough place in the world at large, here on noisy days can seem mere fantasies, or at best childhood dreams that cannot quite be recalled. But what prison life impresses on me perhaps most terribly is not just frangibility of soul, but unlively contempt for what remains: the diminishing expectations, the compromise of aspiration, as each unrecoverable day goes by, accumulating memories that are the stuff of nightmare.

I loathe prisoners, of course, but this means I loathe myself, for I am one, damaged and declining also. If I hold on to my contempt and self-loathing because they keep me in touch with some iota of what I should still yearn for and might have become in a different, challenging, various life, I know how ridiculous that nostalgia is. Under these fluorescent lights, quiet repose—whether scholarly, musical, or otherwise—has the cast of desperate escapism and risible amour propre. No lover given over to reveries of his beloved, condemned to caress her features in fading photographs, could be less fit than a prisoner to distinguish between liberation and escapism. In this sense, prison serves as an apt metaphor for both freedom and determinism—an emblem of their consubstantial uselessness; for prison teaches above all that the future will have no cure for the past, and life no end but the tomb.

There is perhaps one kind of freedom that prison can make you understand as no other experience can. To grasp the indifference of the universe is one thing; to understand the open malevolence of an entire society of human beings is quite another. In the segregation cell, you are confronted with the terrible confluence of both. The world is narrowed to a single dirty room. However many times you are moved, the room is always the same; only the dirt is different. The days are the same as well, and they operate on the same, repeated plan. The food comes in on a tray, the tray goes out. The brief gleam of our lives between dark eternities seems not glimmer but dingy waste. The self and the spirit, you come to realize, do not exist deep within, but extend far beyond you; they exist only through the connection with all of that with which you share an interest. In utter desolation all becomes idle, and even if you know you will get out with some life still left to live, even if you think it will be soon, you feel an irresistible awareness of the senselessness that life is, alone. Even self-mastery can come to seem futile. Become a stoic if you like, and practise resignation, practise your indifference to all that happens; the system continues as before. Hope is irrelevant; only the perpetual loss of the present moment is real, absolute, permanent.

For a long time, I would try to live out in as much detail as possible my memory of days long past and far removed: in Pakistan, sun-bathed reveries on a warm couch, playing with kittens, a precocious first dinner date in a Japanese restaurant. But ineluctably, the memories came to seem indistinguishable from imagination. Once every connection with your past life falls away, you are left with only your presence in the dirty room. There is one relief: nothing is expected of you, you have no responsibilities, you are at ultimate and absolute liberty. But it is the liberty of a man immured in an indifferent mausoleum, awaiting his own extinction.

I cannot say that the isolation cell is the only way to attain even this unhallowed understanding of freedom. As an adolescent, I had already formed an idea of its peril, in the condition of error: alone in a room, checking my incorrect mathematics answer again and again, unable to detect any mistake, and yet seeing my error immediately once it was pointed out to me. Without my father to correct me, I thought, I might have forever remained in error. There is a moment, moreover, in Kafka’s last novel, The Castle, that captures the very emptiness of freedom taken to extremity. The protagonist accomplishes his escape from others, only to find himself estranged in his victory:

It seemed to K. as if at last these people had broken off all relations with him, and as if now in reality he were freer than he had ever been, and at liberty to wait in this place, usually forbidden to him, as long as he desired, and had won a freedom such as hardly anybody else had ever succeeded in winning, and as if nobody could dare to touch him or drive him away, or even speak to him; but—this conviction was at least equally strong—as if at the same time there was nothing more senseless, nothing more hopeless, than this freedom, this waiting, this inviolability.

I read these words in segregation—with recognition. I laughed. In prison as in no other human affliction is there so fundamental and sustained a rupture of human solidarity, so seamless a sense of enmity.

The hell of other people can reach delirious extremes even in segregation. Perhaps especially in segregation. Bad neighbours are nuisances in ordinary life, but the prisoner in a neighbouring cell is never more than a few feet away, and if he is insane, as is often enough the case, life quickly becomes maniacal. A deranged Vietnam vet (if his ravings may be relied upon) once ranted next door to me in an intensive management unit for weeks on end, before being released directly into the free world. Another prisoner, Somali Ali (as he called himself), the first neighbour I had in the King County Jail, was hardly more than a boy, but already long gone. He took me for a liar when I told him I’d been imprisoned six years already, because his head was filled with tales of brutality of incarceration inevident on me. Then he launched into a practised and deafening tirade—“I’m a mothafuckin’ savage, I’m built for this shit”—that went on for days, and which I had to endure without even the mild amelioration of earplugs, which were banned in the jail. He alternated beating upon the wall with emitting scraping sounds that, he assured me, were from the crafting of a shank for the moment when we might come into contact. At one point, he tried to pour liquid through a crack in the wall, before I sealed it with toothpaste and newspaper. Eventually, he attacked a prisoner who was cutting his hair, and they took him elsewhere. A year later, he was shot to death in the prison yard at Walla Walla when he wouldn’t end his assault on another prisoner. By sheer coincidence, my attorney at the time had once been his; it transpired that Ali had been brought to America from Somalia for sexual exploitation by an American soldier. He had been shunted through Washington State’s foster system and its juvenile prisons before being graduated to the adult variety.

To talk of freedom and spirit is obscene here; the lesson impressed upon me most forcefully is how utterly our ears render us the prisoners of others. The eye’s lid has no counterpart in the ear. Not even the best earplugs will do for hearing what we do for vision whenever we, mercifully, shut our eyes.

It is rage rather than freedom that I have come to understand most in prison. I was always more disposed to laughter than to anger, and thought fury a brazen confession of moronic monstrosity. But fury is not so alien to me today. I sometimes wonder how the free might feel if they could know what feelings the prisons they have built can inspire in those forced to live in them. There is no respite from fury in prison. I now need only think of certain things, and hatred from tiny points engulfs the world. When I think of years spent lying awake from the cold, though there were piles of blankets ready; when I think of the years spent without a note of music, though forced to listen to vulgar conversations yelled from cell to cell in the night; when I think of the boorish bureaucrats manipulating the mechanisms of misery with their misspelled memos; when I think of the years without dental floss; when I think of these years wasted by the complacent and comfortable, by the ignorant and the indifferent; when I think of all this completely unnecessary cruelty and then of that world that can find it possible to be upset over desserts that do not turn out right at Christmas—then rage unfolds, and it is possible to wish to bring down the world in ruins.

And yet I despise this fury, too, because it is finally so petty and useless, so unworthy, so unfree; so much a prisoner’s emotion from which there is no escape, so much the very brand of bondage. Nevertheless, I feel this abhorrence must not be lost, for it is connected to the admiration of its opposite. To lose it entirely would be to have relinquished all expectations of a possible world governed by living ideas of care and beauty, and animated by the faith that the reach for the sublime, the evanescent voice of a violin in a void, even in prison, perhaps especially in prison, matters still.

Ishould be the first to concede that the abjection to which jail—a far worse place than prison—reduced me is tremendously funny. All in all, I am glad I can still find the recollection of the sheer erasure of human dignity so full of mirth, as I discovered in talking of the ordeal one recent morning with another prisoner who had been there at the same time I was, and for almost as long. From the remove of our very relative, entirely comparative safety, we could laugh, with the terribly energetic hilarity of relief, at the common, indelible memories. Memories of waking long before dawn from hunger pangs, in the purple half-light that glowered all night, only to await like dogs, with inane anticipation, the plastic trays bearing a breakfast consisting of a single egg, a single cup of porridge, three slices of “brown” bread, a half-pint of milk, and the junk I never ate—the margarine and packets of sugar and drink flavouring. Of the ravenous, animal hope that the oatmeal would be thick, followed by disappointment when it was as thin as saliva. Of yet how rapidly that disappointment would give way to greedy, animal satisfaction in scraping every drooling iota of gruel off the tray. Of grovelling with just the right mixture of effortful plaintiveness and amicability for an extra leftover sack lunch.

Memories of thanking departing prisoners for the foul gift of their used sheets, to be traded in on the weekly exchange so I might have two with which to ward off the cold. Of frantic desperation in trying to get the attention of the functionary who was sent, after months of prisoners’ complaints about the frigid cells in which we shivered, to take the temperature, but who officiously measured it—the face so bland, so warm—in the toasty, hot core of the building where the guards ate takeout and cackled. Of the obese, porcine body and stolid visage of the senior administrator with the ridiculous rank of major, who received without a trace of irony the solicitous words of a judge about the excellence of the facility and the difficulty of his constraints. Of spending the entire hour permitted outside the cell in the shower, to keep warm. Doing it all naturally, complaisantly, as though dignity were something that did not exist.

This may not seem quite entirely funny. The humour may be, to some, a touch elusive. The comedy comes from the droll reversal by which brutality assumes the mantle of righteousness precisely by the victory of its own insensibility, or rather, its imbecile sensibility. It abides in the constant ironic suppression of outrage in an environment in which the irony will never be perceived, and the constant acceptance of unacceptable cruelty that will never be recognized as such because it is established—it is the absolute entrenchment of evil among human beings too banal to recognize it as such. I can laugh at all this, until my stomach contorts into iron knots, in much the same way that I laughed uncontrollably one day after the recitation of an impeccably mannered young graduate student teaching sociology, who delivered in her well-constructed paragraphs, with the aptest expressions of face, voice, and word as cues of moral disapproval, an account of the plight of the mentally ill in Soviet asylums, held in cages and blasted with icy water from hoses as they protested incoherently. The laughter mixed relief at being removed from such futility and suffering, and a sense of power in having the capacity to perceive its abjection. Since I have a far happier conscience when laughing at cruelty directed at myself, I find my own memories even funnier—however much I might want to disapprove.

Iknow now, better than I should like, my bare requirements for a life recognizably human, perhaps recognizably mine: the seclusion of the single cell; the adequate food; the blessed if imperfect earplugs; the books, papers, and music; the tenuous strands of hope that ravage what they sustain. I know that prison is not a space for understanding freedom, but a place of creeping corruption. What I love nonetheless in Gould’s words is that they sound a tune to which our ears are unaccustomed—one that promises of perfections not yet imaginable, of freedoms as yet unconscious, even if they are not here. Life is problematic; something is missing; ardour is of it.

I am tempted to think that Gould came to comprehend why prison could not have given him the understanding he sought. The paradox of freedom through toil, in toil, is perhaps never more vivid and yet more consummately vindicated than in the performance of written music. The pianist is asked to train in sinew and nerve to reproduce with exactitude a score not of his own devising—to maintain fidelity to this text. Yet this feat is achieved not merely when the technical difficulty of the work is no longer an obstacle, but when the score is so thoroughly absorbed that it belongs completely to the performer. The performer then becomes an interpreter and comes at last to share in the inner texture of the relationship with that ineffable other with which the composer was engaged when composing the work. Just as we do not originate the language we speak, but nevertheless by learning it liberate our individual power of expression, so learning a piece of music does not make the pianist merely a slave to the composer. There is no question of struggling against the composer to express oneself. Rather, the very chains of the composition become the means for expression, and the space of freedom for the imagination.

Gould was the paragon of a creative interpreter, and in the years after his breakthrough record his playing continued to develop. His recordings eschewed wilful romantic extravagance without ever ceasing to be personal or poignant. In the essay he wrote early on to accompany his recording of the unsurpassable last three piano sonatas of Beethoven—Beethoven, who claimed that music is a higher revelation than all of wisdom and philosophy—he avoids hyperbole to emphasize instead their subtler charms and quieter satisfactions. Nabokov was impishly fond of puncturing clichés about the opposing cultures of science and art (both, in his view, philistine) by extolling the passion of pure science and the precision of poetry; the best of Gould’s recordings annihilate any sense of contradiction. In these interpretations, analytic clarity and absolute control become inextricable from and indispensable to originality of expression and imaginative freedom. Nothing is merely wayward; nothing is for effect. He serves the composition, and it serves him in a beautiful equipoise.

A quarter century after that first celebrated recording, Gould was moved to record The Goldberg Variations again. He could not have known that it would be his final record. In one of his last interviews, he explained his dissatisfaction with what he now considered the faults of his earlier interpretation. “The purpose of art is not the release of a momentary ejection of adrenaline,” he finally averred, “but is, rather, the gradual, lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity.” A state of wonder and serenity—nothing is so far removed from prison’s unhallowed halls.

And yet prison is not, after all, without its cruel, special illuminations. Reverence, that rarest of virtues, peeks out from time to time. If the hanged man on the gallows holds the entire world in balance, so does the prisoner have a free view. Sisyphus is indeed of most interest precisely at the moment of leisure, in repose before the toil begins anew. In the silent moments of darkness, after the lights go out, when a gleam lights a page or headphones resound, nowhere so much as in prison do the pejorative connotations of the term “escapism” lose their point—if not, perhaps, all their sting. The work of art is more than luxury or decoration in prison; it can become the substance of life itself. Here, in the very pit of crude fatuity and dull compulsion, those works of human frailty, those arts that were once the privilege of liber—the free, the rich, and the mostly happy—assume an overwhelming and astonishing significance for the wretched, as if their inmost savour and secret, the elusive quality of their perfection, had been hidden away undisclosed, awaiting this only too human need.

I must imagine it some consolation still—only not happily, nor, happily, ever after.

This appeared in the April 2011 issue.