This year marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Northrop Frye, the world-renowned literary critic, essayist, and editor who accumulated over thirty honorary doctorates and more awards than Meryl Streep. He spent his career at the University of Toronto, where I studied English literature many years later. I took graduate seminars with his former students, who kept office hours in the aptly named Northrop Frye Hall. I struggled through Anatomy of Criticism and wrote papers on The Bush Garden. I heard the anecdotes and came to understand his influence on the department, on the university, on the field. But when I think about the centennial of Frye’s birth, I do not think about archetypal criticism or William Blake. I think of Fort York in downtown Toronto.

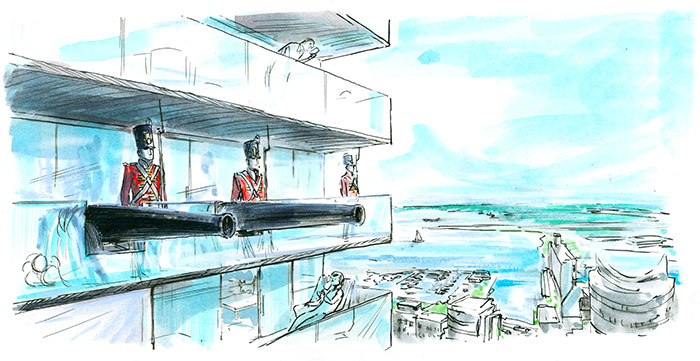

Perhaps it is because I have been spending a lot of time at Fort York, arguably the symbolic epicentre of the ongoing War of 1812 celebrations. Usually, I walk there from my office or condo, but a couple of weeks ago I took a taxi. When you drive to Fort York, you approach the nineteenth-century garrison from the west, passing under the Gardiner Expressway onto a gravel parking lot not far from the shores of Lake Ontario. You see the historic earthworks, the cast iron cannons, the Union Jacks. But overshadowing it all, you see CityPlace, a gleaming residential development with twenty skyscrapers and counting, towering in the east.

For me, the coexistence of these disparate spaces—separated temporally and physically by two centuries and the north–south artery of Bathurst Street—embodies the interconnectedness and originality of Frye’s most provocative ideas about Canadian culture. On the west side of Bathurst, you have the “garrison mentality,” the notoriously divisive concept he developed early in his career. On the east side, you have the “condominium mentality,” an aphoristic phrase he coined near the end of his life. And this juxtaposition, of the country’s colonial past and its high-rise future, feels uncomfortably poetic.

Born in Sherbrooke, Quebec, and raised in Moncton, New Brunswick, Northrop Frye is said to have defined the twentieth-century Canadian imagination. Trained at Victoria College at the University of Toronto and Merton College, University of Oxford, he established his reputation in literary studies with Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake (1947); but it was his ambitious Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays (1957) that made him world famous. Not primarily a Canadianist, he was nonetheless an expert on his country’s literary and cultural history.

He developed his expertise through decades of “field work”: reviews and essays on contemporary fiction, drama, painting, and, especially, poetry. In assessing A. J. M. Smith’s The Book of Canadian Poetry: A Critical and Historical Anthology (1943), for example, he observed, “The colonial position of Canada is therefore a frostbite at the roots of the Canadian imagination, and it produces a disease for which I think the best name is prudery.” In his annual University of Toronto Quarterly Letters in Canada essay for 1952, he identified our most distinctive cultural feature as “some feeling for the immense searching distance, with the lines of communication extended to the absolute limit, which is a primary geographical fact about Canada and has no real counterpart elsewhere.”

He addressed the effects of that searching distance again in the concluding essay he wrote for Carl F. Klinck’s anthology Literary History of Canada (1965). There, he used the phrase “garrison mentality” to characterize early Canadian literature: “communities that provide all that their members have in the way of distinctively human values, and that are compelled to feel a great respect for the law and order that holds them together, yet confronted with a huge, unthinking, menacing, and formidable physical setting—such communities are bound to develop what we may provisionally call a garrison mentality.” Paralyzed by the sublimity of nature and vaguely defined hostilities, settlers huddled together in isolated communities carved from the wilderness. “A garrison,” Frye explained, “is a closely knit and beleaguered society, and its moral and social values are unquestionable.”

The conclusion was hugely influential, and has been hailed as a “cultural icon” and “one of the classics of our criticism.” Following its publication, other writers explored its larger implications, most notably Frye’s student Margaret Atwood, who published Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature in 1972. Some, of course, rejected the phrase and the ideas behind it. But whether or not you subscribed, it was virtually impossible to discuss Canadian literature in the latter half of the twentieth century without engaging the garrison mentality on some level.

Years later, in the fall of 1989, Frye delivered a speech at the Canadian Embassy in Washington, DC. Speaking in architect Arthur Erickson’s new chancery, the storied professor explained that he had intended the garrison mentality to “describe the psychological effects in Canada of the Anglo-French wars, fear of Indian attacks, and protection against an implacably indifferent nature, with its cycle of intense heat, intense cold, and the coming of spring along with the black flies.” Critics, however, had “over-exposed” his phrase, and “like other over-exposed images [it] has got blurred and fuzzy, its specific historical context being usually ignored.”

“As I understood it,” Frye continued, “a garrison brings social activity into an intense if constricted focus, but its military and other priorities tend to obliterate the creative impulse.” Conditions changed throughout the nineteenth century, yet the garrison mentality remained “psychologically in the rural and small-town phase of Canadian life, with its heavy pressures of moral and conventional anxieties.” For the majority of late twentieth-century Canadians, “one of the most highly urbanized people in the world,” the garrison mentality, “which was social but not creative,” had been replaced by “the condominium mentality, which is neither social nor creative, and which forces the cultural energies of the country into forming a kind of counter-environment.”

While critics have contested the concept of a garrison mentality, Frye’s notion of a condominium mentality has drawn surprisingly little attention. But whenever I approach Fort York from the west and see CityPlace in the east, it’s clear that the two ideas are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, they inform each other and suggest that Frye anticipated the type of twenty-first-century lifestyle that I, and thousands of other Canadians, now lead.

We tend to forget that condos, to say nothing of the high-rise developments that have come to dominate the country’s urban skylines, are a rather new form of property ownership. The word “condominium”—derived from the Latin words con (“together with”) and dominium (“right of ownership”)—emerged in the early eighteenth century, but the modern definition of “a building or complex of buildings containing a number of individually owned apartments or houses” only came about in the 1960s. In North America, the condominium as a legal form of ownership was established in the United States in 1961. British Columbia’s Strata Titles Act, passed five years later, paved the way for the ownership model here; within a decade, condominiums were a legal form of property throughout the country. When Frye critiqued “the anti-cultural environment [of] introverted big-city living,” condos had only existed in Canada for twenty-three years. Twenty-three years later, more Canadians than ever own or live in one.

Condos have been praised for their socially and environmentally transformative potential, as a legal construct that creates citizens with private, financial stakes in the well-being of their communities. Through the subdivision of horizontal and vertical space, they democratize property ownership, counteract urban sprawl, and reduce pressures on the environment.

Canadians are especially fond of them. Consider Metro Vancouver, in which 31 percent of owner households are condominiums. In Vancouver proper, which aspires to be the world’s greenest city, that figure is even higher, at 37 percent. (Three decades ago, fewer than 10 percent of the region’s residents owned a condo.) In the Greater Toronto Area, an urban centre with more high-rise condominium construction than anywhere else in North America, more than 21 percent of homeowners live in condominiums. These figures do not account for the substantial number of condo dwellers who rent. All in all, some 11 percent of Canadians called a condo home in 2006. We won’t have relevant data from the 2011 census until September, but it doesn’t take a statistician to tell us that the number is now much, much higher.

But for all their transformative potential, environmental benefits, and economic stimulus, condos have their detractors. Critics have long maintained that they are mechanisms of exclusion, gentrification, and middle-class affectation. Large- and mid-scale developments often demolish low- and moderate-cost rental housing and displace commercial and retail tenants, creating functionally gated communities in their place. Researchers have pointed out that many buyers view their purchase as a stepping stone to freehold home ownership, thus complicating the assumption that owners feel invested in their communities. And anecdotal evidence from developers and real estate brokers suggests that foreign investors—particularly those from Europe, Asia, and the Middle East—make up a large percentage of condo owners in Canada, essentially functioning as absentee landlords with financial but not cultural stakes in a community’s well-being.

Still, let’s put all of that aside and pretend that our condo market will continue to thrive, that we’ll avoid a US-style housing bubble, that newly constructed condominium developments will remain desirable places to live in the decades to come, and that predications of ghettoization will come to naught. Even if we assume all of that to be true (a big assumption), our collective condominium mentality should nonetheless give us pause.

Areviewer once described Frye as a critic who had “the courage to confront the present without distaste, the past without nostalgia, and the future without fear.” Frye himself dryly remarked that he entered areas “thickly sown with emotional minefields.” But while he was a prescient thinker, it seems unlikely that he could have imagined a minefield quite like CityPlace, to say nothing of countless other developments across the country (Vancouver’s Yaletown comes to mind).

Built on a sizable portion of CN’s former railway lands, CityPlace is the last phase of a fifty-year redevelopment effort that has included the construction of the CN Tower, the Metro Toronto Convention Centre, and the Air Canada Centre. When completed, the eighteen-hectare project will encompass at least 11,000 units, divided among twenty-three shining towers. Developer Concord Adex, part of the Vancouver-based Concord Pacific Group, has allocated just under 50 percent of the site to parkland, boasting that CityPlace will have “more green space than any other neighbourhood in downtown Toronto.”

When I walk around CityPlace, what strikes me, beyond its scale, are the similarities to the historic garrison next door. First and foremost, it is largely self-contained and introverted; the majority of the site is bounded by Bathurst Street to the west, a rail corridor to the north, and the Gardiner Expressway to the south. Spadina Avenue, a pedestrian gauntlet, separates a smaller portion of the development to the east. The thoroughfares and train tracks function as modern fortifications and moats, offering residents protection from the hostilities of Toronto. The central green space, accentuated by an oversized canoe designed by Douglas Coupland, recalls a military parade ground, with neighbourhood hounds marshalled about by their dog walker sergeants. In the event of a siege, denizens are well equipped: they have a canteen (Sobeys), vaults (Royal Bank, TD Bank, CIBC), and numerous watering holes. In the event of inclement weather or bombardment, they can move from building to building without actually having to go outside. Even structures that house the development’s common amenities (the pool, the gym, the movie theatre) display a dash of military flair: chain mail curtains provide the right combination of privacy and intimidation. Surely, this is the type of development political scientist and housing critic Evan McKenzie had in mind in 1994 when he anticipated “a return to the ancient concept of city as fortress, in which society’s haves huddle to defend their lives and possessions against the have-nots outside the gates.”

Though much larger, CityPlace is not unlike my own condo three kilometres to the east, in the old garrison town of York. My two-year-old building—one of Frye’s counter-environments—does little to encourage residents to explore the larger community, to mingle and interact with outsiders. It doesn’t enforce prudery, but neither does it foster creativity. Designed by one of the city’s top architects, it’s not a terribly inspired structure (I can count a dozen others within a two-kilometre radius that look just like it). And that’s only the edifice; it gets worse inside.

Unlike a garrison, which Frye saw as a social unit, my building offers the illusion of community while cultivating insularity. We take the elevator to the lobby or the underground parking garage, fiddling with our iPhones instead of visiting with the person standing next to us. We post complaints about our neighbours’ barking dog on “community-building” Facebook pages, rather than knocking on their door and having an actual conversation. We threaten to call the cops when our neighbours enjoy their balconies, instead of joining them for a beer. We flip our units as soon as we can afford a better one in a better building, or as soon as our view is destroyed by a rival development down the street. We’re all alone with our high-speed Internet and embarrassment of social networks, as concrete walls mute the existence of our real neighbours.

On a recent trip to Buenos Aires, I noticed that high-rise condos there were different than ours in one key respect: they lack commercial and retail space at grade. If a Porteño wants a morning coffee, he is nudged into the larger community. Here, we complain on Facebook about there not being a Starbucks on our block and about having to walk an extra fifteen metres to the grocery store. A stroll through the neighbourhood can (and should) be a leisurely pursuit, a time to think, to imagine, and to cross paths with those who are different than us. But we forget this. If colonial settlers were afraid of the outdoors, we simply can’t be bothered to go outside or look up at it from our smart phones.

None of this is to suggest a rejection of condo living, or to say that I don’t feel at home in my building. It’s just that I can hear Frye mocking me and my text-messaging neighbours in that deadpan tone of his.

It would be difficult to overstate Northrop Frye’s influence on the study of Canadian culture, and literary studies around the world, just as it is difficult to review concisely his sizable body of work. But he offered a primer in 1962 when he delivered the second CBC Massey Lectures, published as The Educated Imagination in 1963. There, he emphasized the essential importance of education in literature and the arts, and he cautioned his listeners against an overly rapid rate of societal and cultural change: “In a society which changes rapidly, many things happen that frighten us or make us feel threatened. People who can do nothing but accept their social mythology can only try to huddle more closely together when they feel frightened or threatened, and in that situation their clichés turn hysterical.”

Our twenty-first-century mythology posits that condos are righteous, sexy and trendy, and good for the environment. (That’s what the billboards say and why I moved into one.) Challenging that mythology is not about whether we should build future developments or abandon them entirely; it is about how we take on condo living in a socially engaging and culturally imaginative way. Frye did not distrust change, but he did question our ability to judge accurately—to judge creatively—the effects of hurried change, especially when it seems like a given.

Before he died of a heart attack in 1991, Frye was interviewed by CBC broadcaster David Cayley. “The condominium is neither cultural nor social,” he maintained. “It is perhaps another, well, ‘threat’ is too strong a word, but it’s something one has to cope with.”

So, how are we coping? Like the garrisons of yesteryear, condos serve a purpose. For more and more of us, that purpose is increased density, walkable communities, simpler upkeep, smaller footprints, and democratized property ownership. But in terms of social integration and cultural creativity, the condo is still a beta concept, which we haven’t yet managed to fully troubleshoot.

When Frye derided Canada’s condominium mentality in 1989, I was seven years old and living on a farm. The only garrisons I knew were the ones I built out of Lego; I had never seen a condo. But when I read his speech now, I feel as if he’s speaking directly to me. I don’t think I’m coping with my own condominium mentality very well. I haven’t bothered to ask my neighbours how they’re coping with theirs.

This appeared in the May 2012 issue.