Alain Pilon

Alain Pilon Kate O’Connor

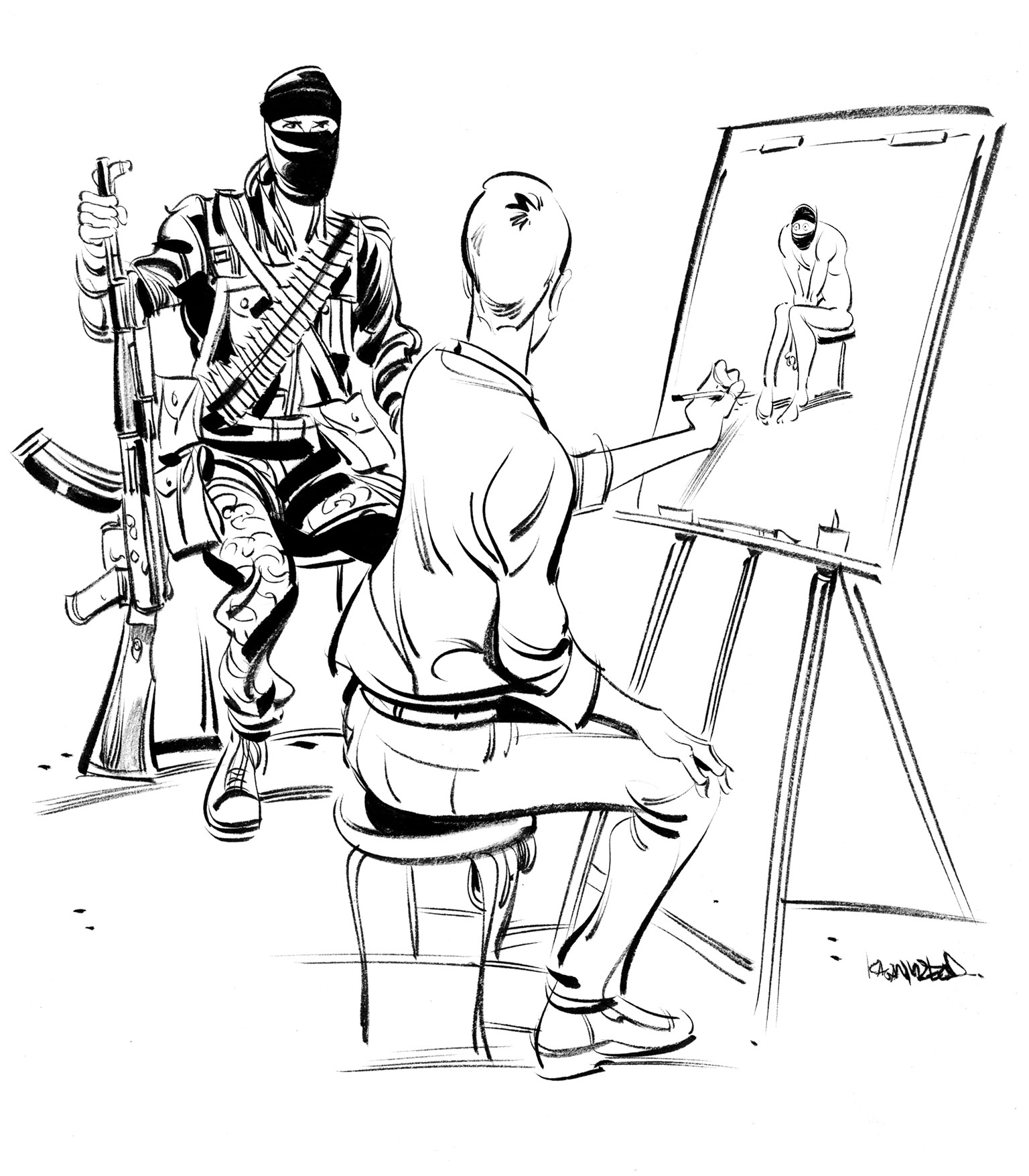

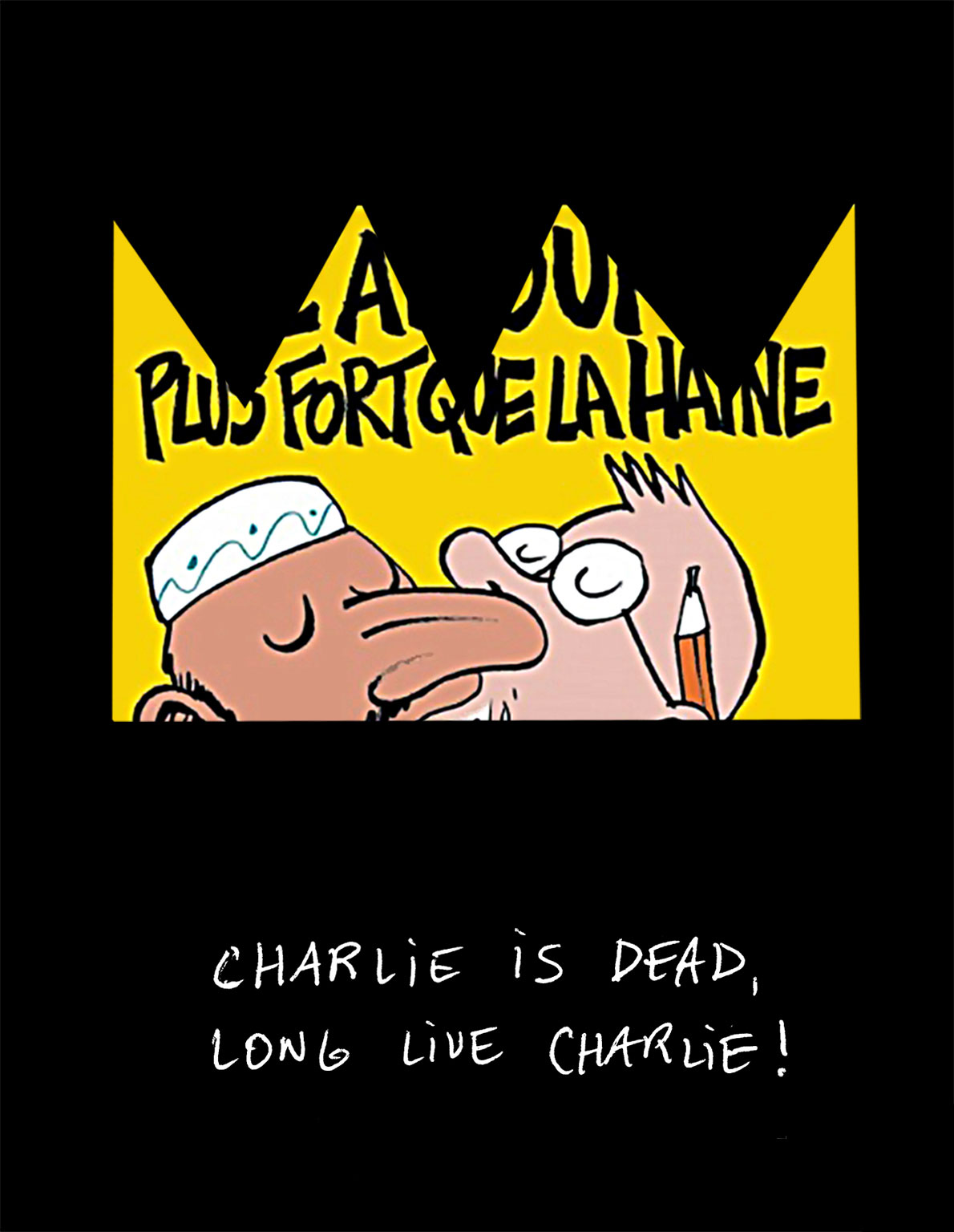

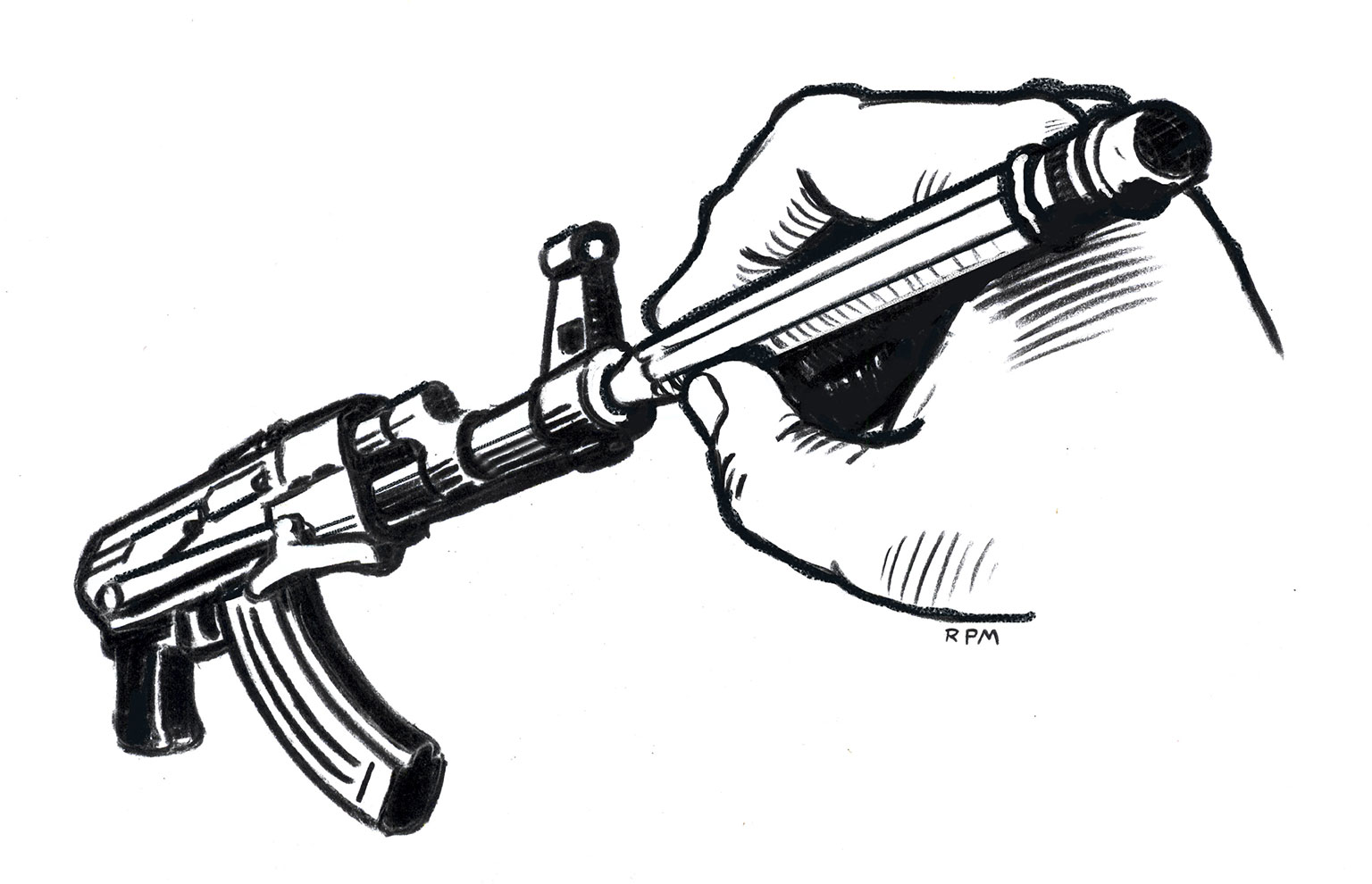

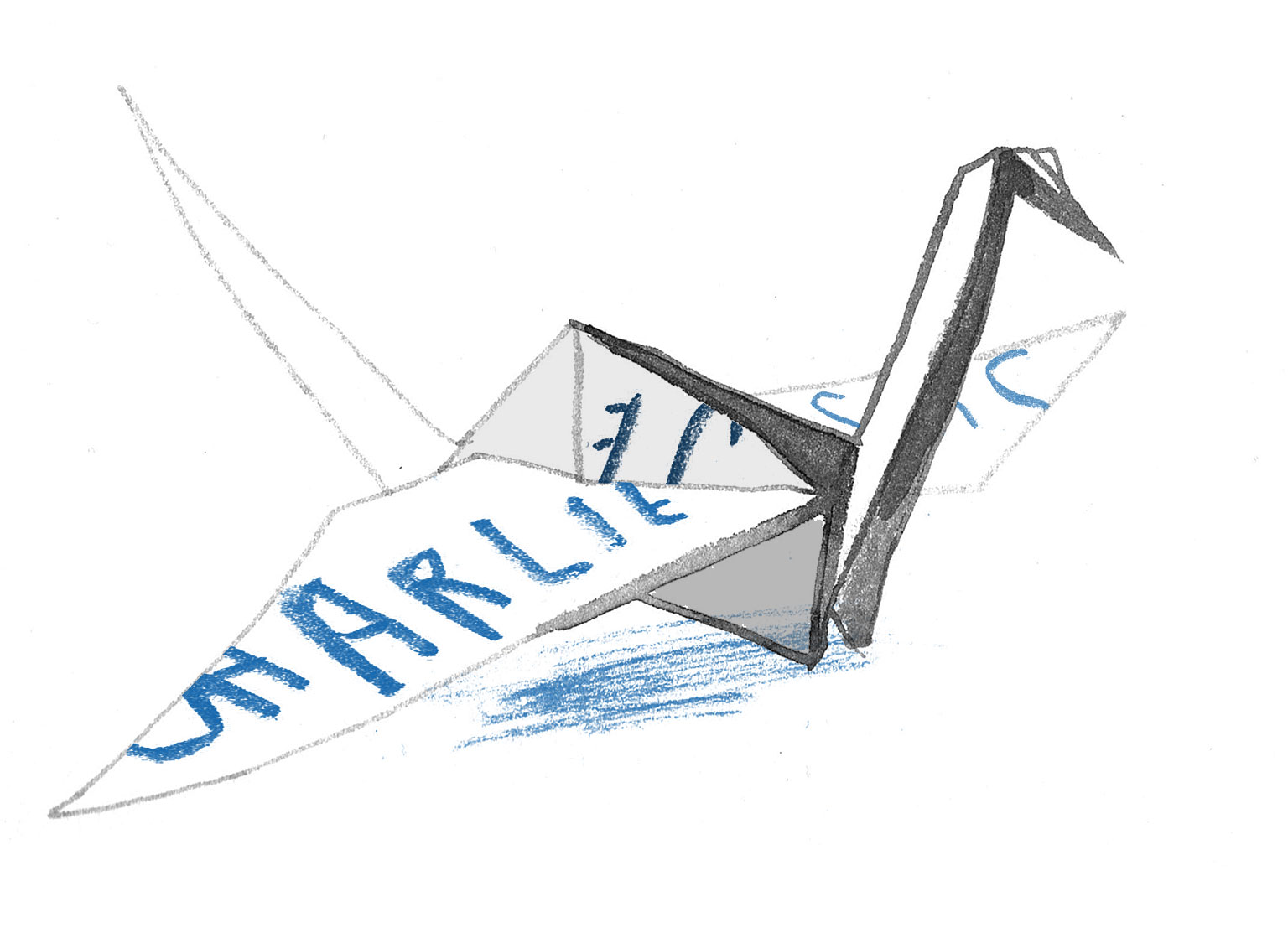

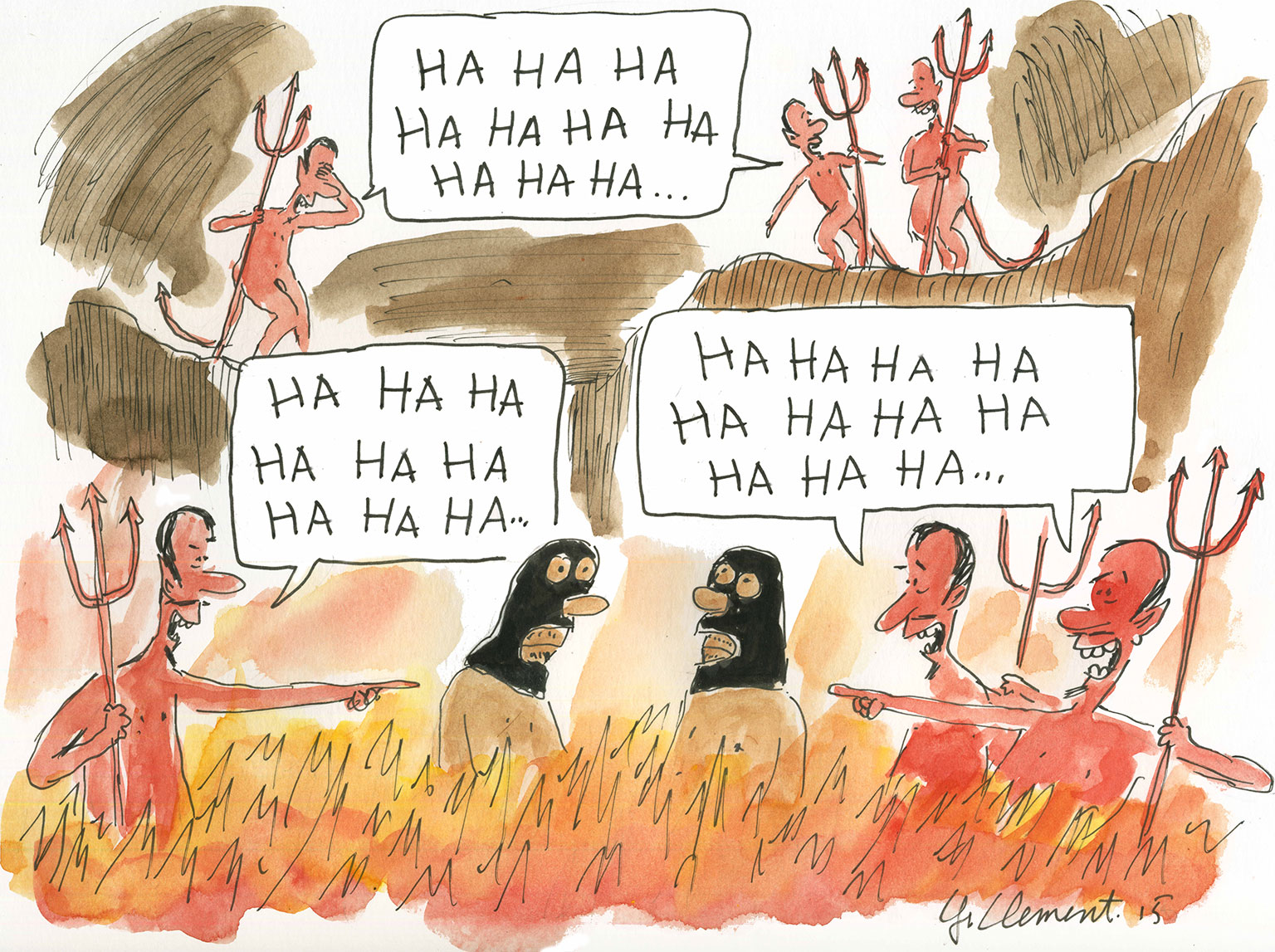

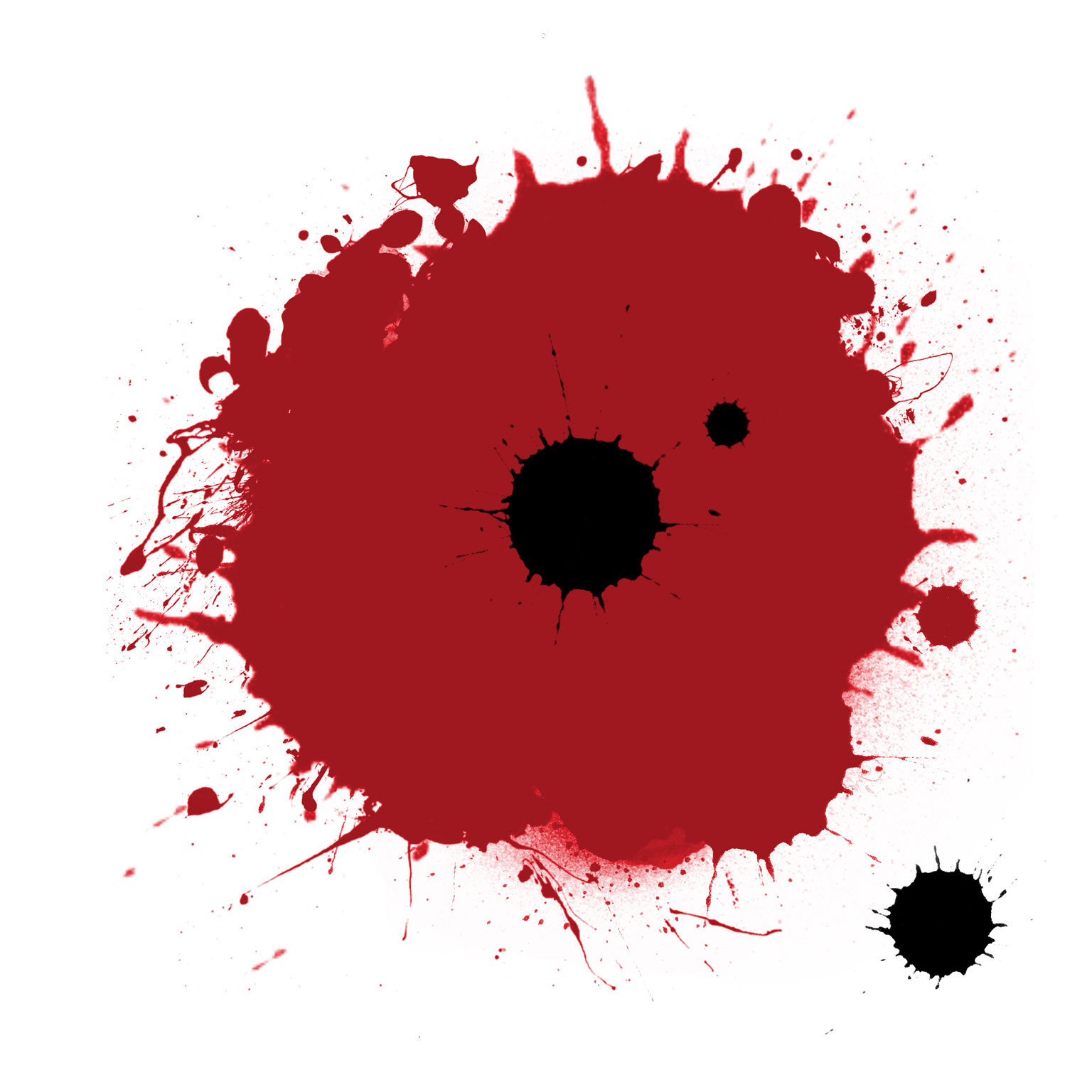

Kate O’ConnorI was asked to produce a cartoon for The Walrus in response to the Charlie Hebdo shootings. After perusing the Internet for references, a certain type of image bubbled to the surface: I have seen many cartoons featuring bearded and turbaned men of colour, as well as masked paramilitary soldiers in Middle Eastern garb. These characters emerge as catch-all punchlines, or universal foils, produced in solidarity with Charlie. It’s as though we want to tell a tenth of the world’s population—and every guerrilla, militia man, and freedom fighter who has ever lived—that we’re not going to take anymore of their crap.

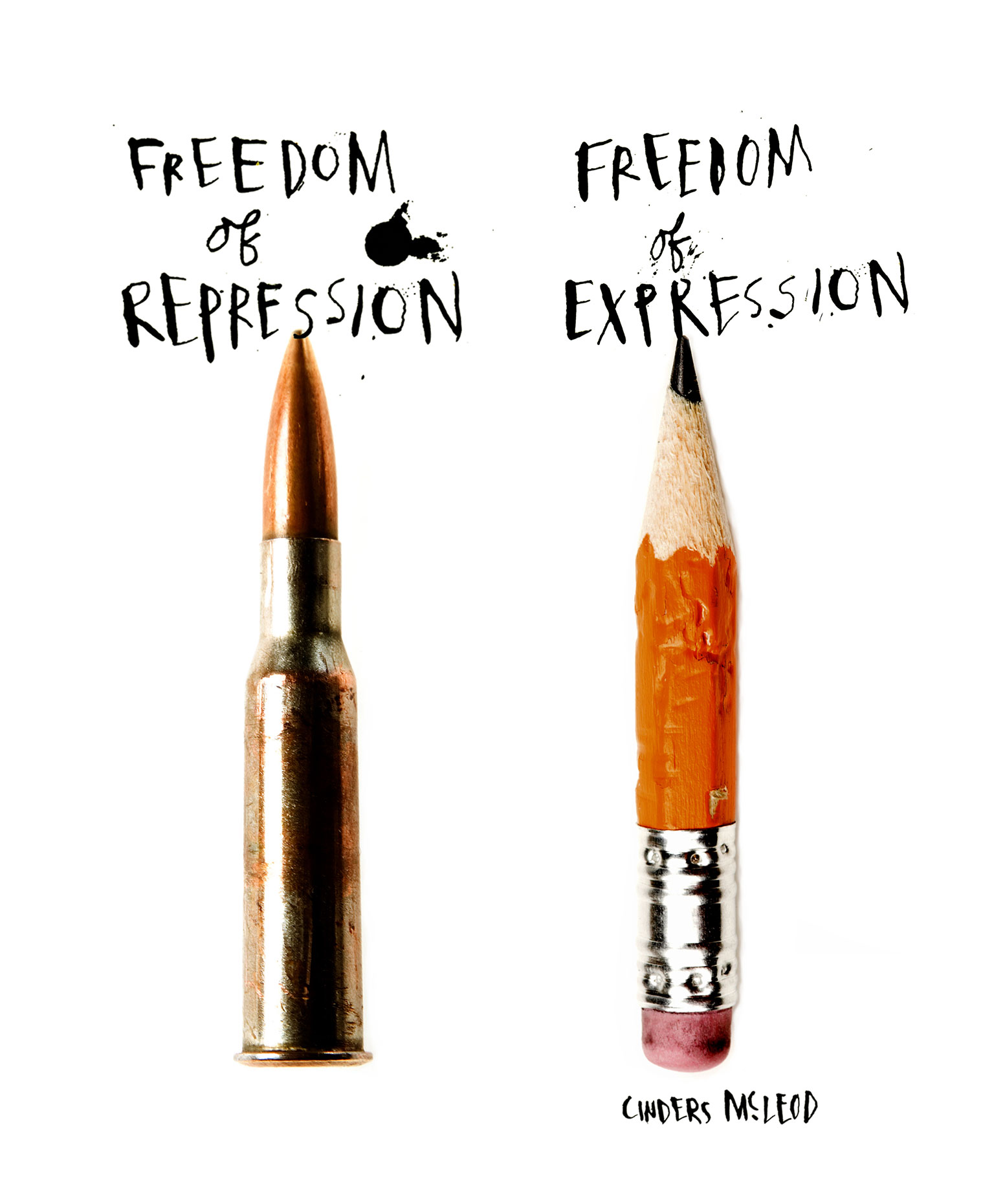

The problem with depicting a ethnographic enemy in cartoons, such as these black-clad meta-Arabs, is that the images end up having very little to do with free speech, what we have set out originally to defend. These cartoons end up functioning as the opposite: propaganda. You can see a similar aesthetic tool used in twentieth-century recruitment posters for our big wars, depicting the dehumanized and racially exaggerated “other” that the government will pay you to murder. Free speech is not about rallying cries against a vision of a foe. It is about including converging and uncomfortable narratives in the public discourse; it is about discussing all sides of an issue, including some that challenge our position of moral absolutism.

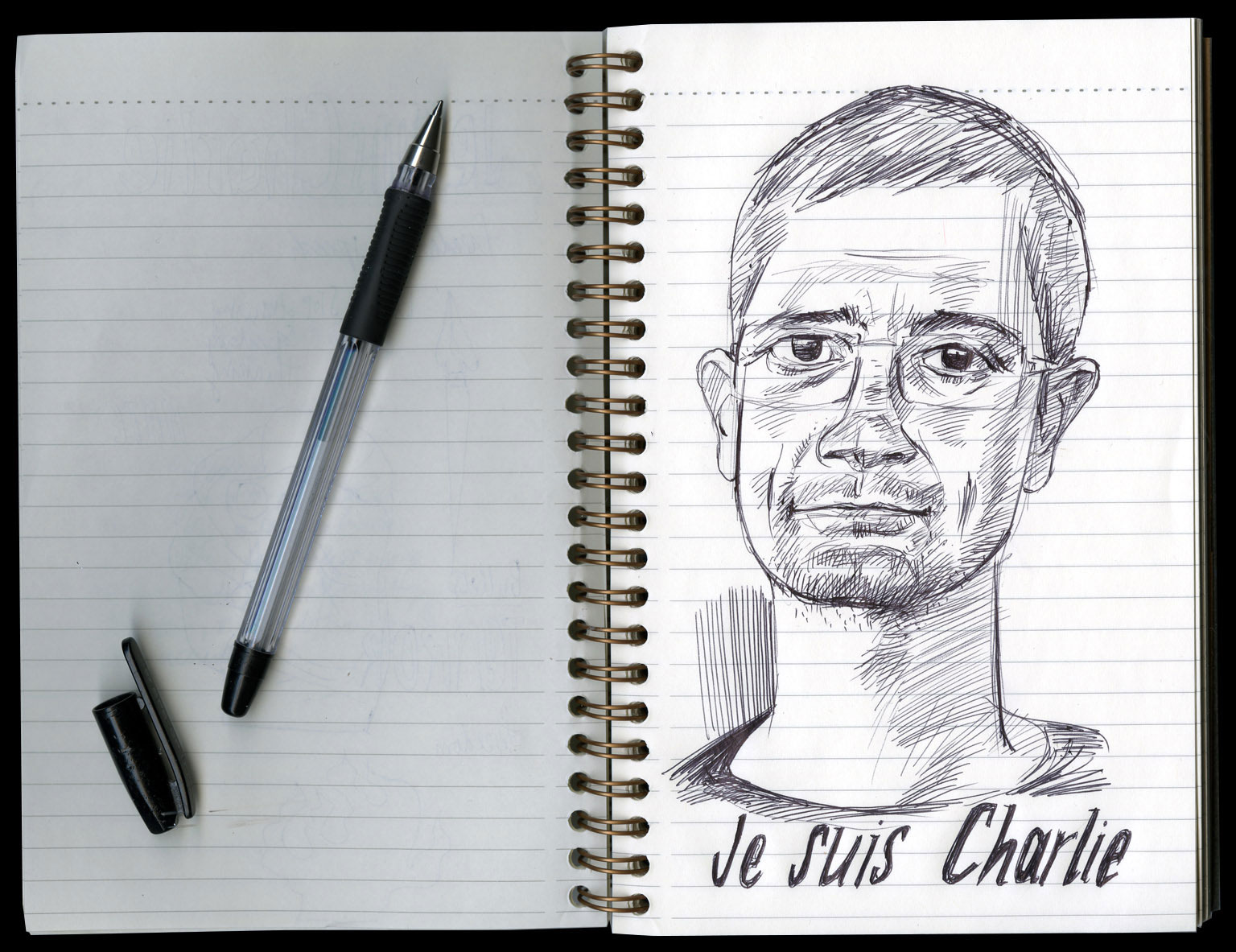

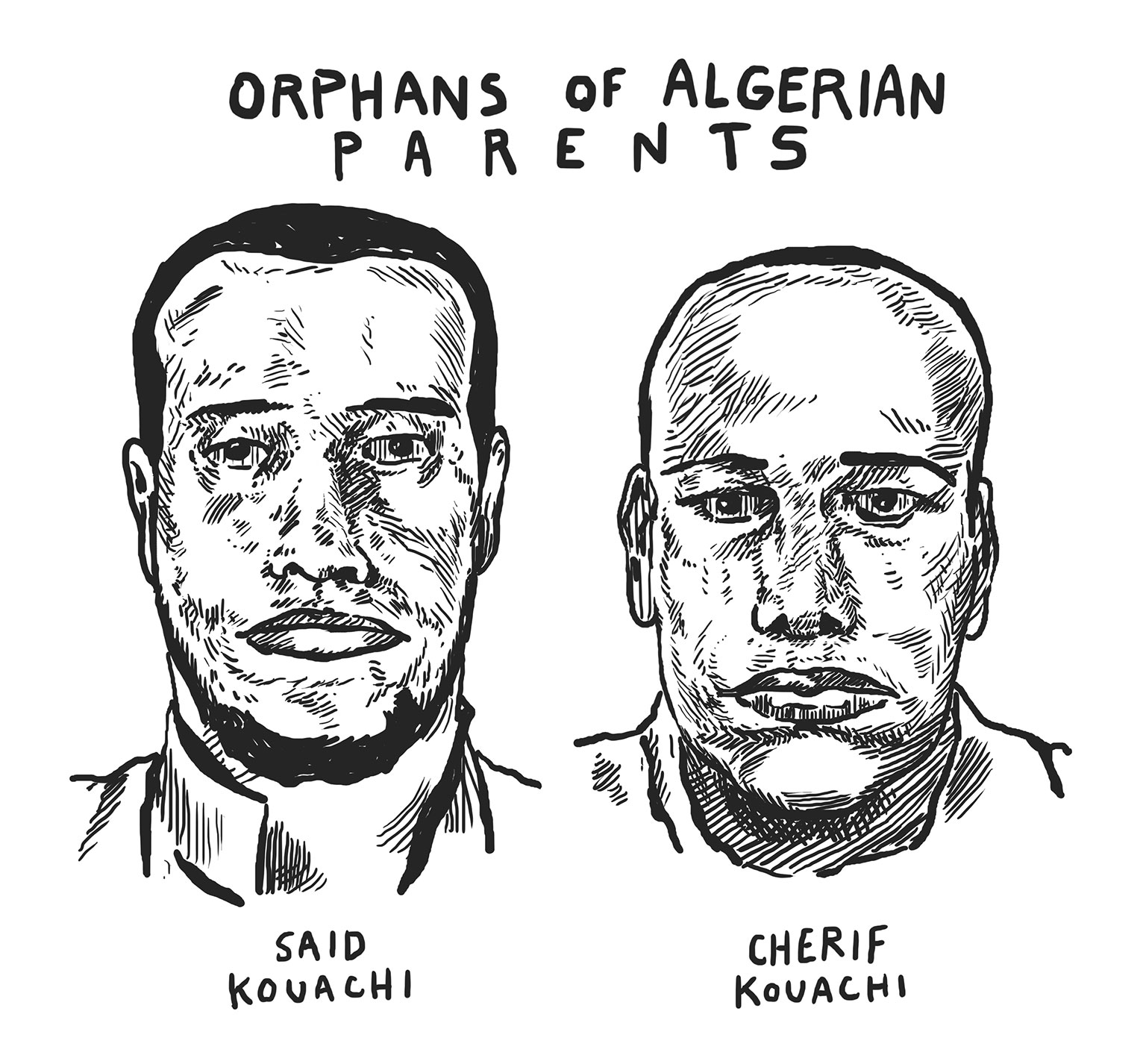

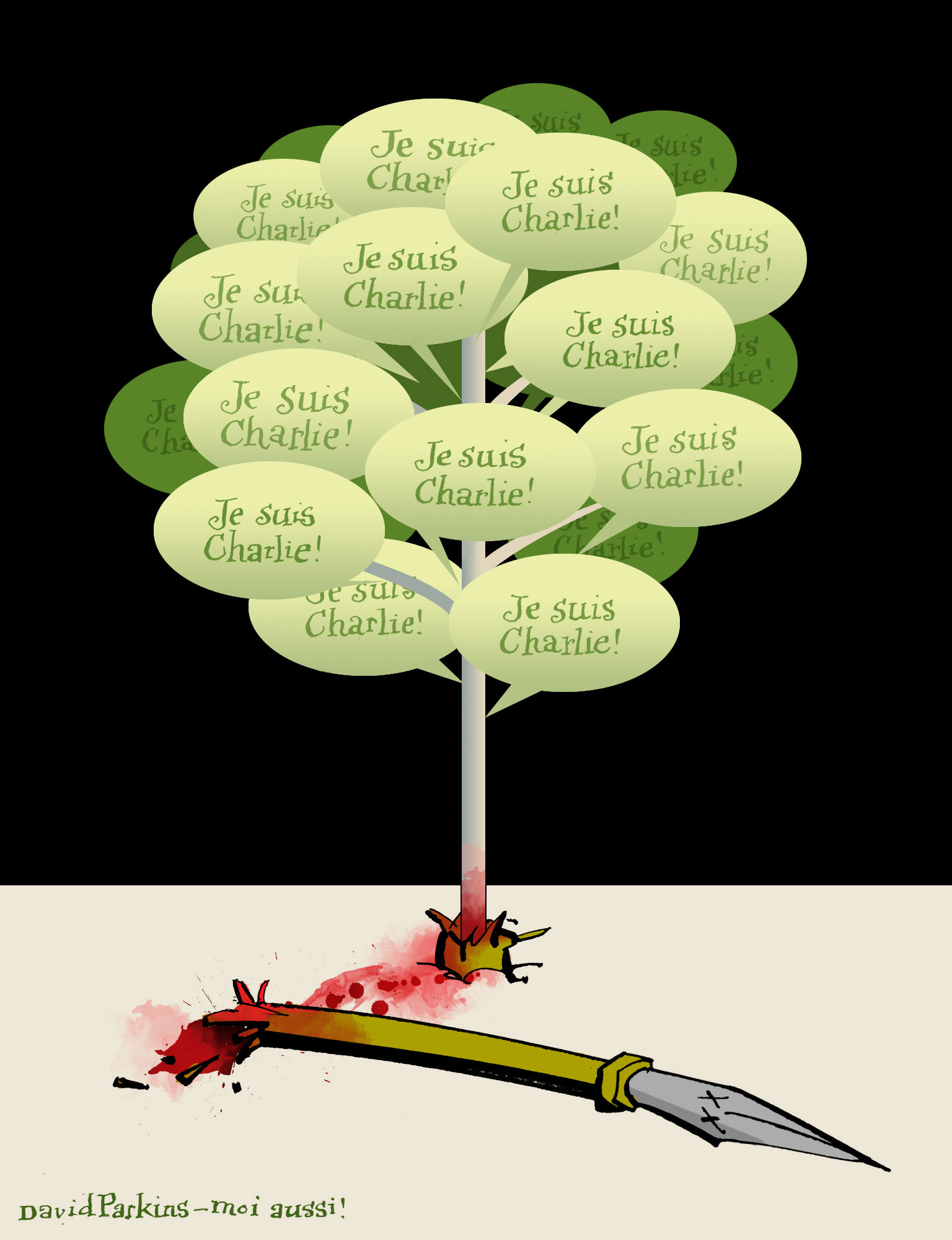

The search for meaning in tragedy is very human. We want this attack to be symbolic of terrorists hating our freedom of speech, but it did not occur in a vacuum. The attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo—like a cartoon of the prophet Muhammad—is symbolic. The two suspected gunmen I have drawn here—Said and Cherif Kouachi—come from a historical context. The reduction of these human beings to caricatures (of ISIS, of al Qaeda) serves to narrow our freedom to think about that historical context. These brothers hail from one of the most marginalized and systematically oppressed groups in French society. A group that has been relegated to live in ghettos without representation—visual or democratic. To reduce the attack to a symbol of evil versus freedom is to narrow our eyes to just barely discern the shape of what we want to understand. This was not an example of international terrorism, but the acts of oppressed French citizens whose family history includes military occupation, racism, and colonization.

I’d like to publicly acknowledge the constant help given to me by my wife, Marie-Josée Parent, in conceiving of this drawing. Her wisdom and sensitivity to the lives of others is a constant reminder and encouragement to me to think before I act.

—Ben Clarkson

Gary Clement

Gary Clement Dushan Milic

Dushan Milic