I am standing with my husband on the curb of Military Road, in a thick fog that has crept over the cliffs of Cuckolds Cove and tumbled over Signal Hill and St. John’s Harbour, past the boarded-up Bargain, Bargain, Bargain store on Water Street, and the old Newfoundland Telephone building, with its busted-out windows, on Duckworth Street. The fog is wending its way inland, circling our knees and eventually spreading toward the overpass. Beyond that point, the fog obliterates the stunted trees, the ponds, and the giant, lichen-mottled boulders of the barrens. It’s a week before Christmas, and we’re waiting, with other gathering spectators, for the mummers’ parade to come around the corner.

Everywhere you go these days, people are talking about Danny Williams’ abrupt departure from the office of premier and what it means for the province. A certain kind of economic growth has followed the thriving oil industry, and the signing of an agreement for hydroelectric development of the Lower Churchill River, a drawn-out negotiation that ended with a profitable arrangement for Newfoundland, unlike with the much-lamented Upper Churchill, given away for a song by Joey Smallwood in the late 1960s.

The oil boom has changed circumstances dramatically, bringing an unprecedented spike in property values. Expats in places like Fort McMurray, who found themselves priced out of the Alberta housing market five to ten years ago, are now buying retirement homes back in Newfoundland. Meanwhile, rent in downtown St. John’s has soared, making it difficult for single parents, students, and other low-income tenants to find adequate housing. Kathy Dunderdale, the interim premier, is determined to thaw Newfoundland’s notoriously icy relations with Ottawa, a conflict that came to a head during a battle over transfer payments in 2004 that culminated in Williams removing the Canadian flag from all public buildings. The dispute was settled and, for the first time since Confederation, Newfoundland became a have province. But it’s a fickle status that seems to be a matter of interpretation rather than a summation of the facts. Months later, we were demoted back to a have-not. One of the most witty and succinct statements on our economic positioning was a neon sign created by visual artist and CBC Radio broadcaster Angela Antle, which read “Have Not,” with the “Not” blinking on and off.

My husband, Steve Crocker, a sociology professor at Memorial University in St. John’s, says this economic growth is deceptive: “Rural Newfoundland is still in decline. Schools are amalgamating, services are deteriorating, and the population has been forced to suspend their way of life to go west, as part of a new kind of global shift work.” Indeed, Newfoundlanders are still commuting cross-country to find employment. Many of the Super Elite passengers on Air Canada flights out of Newfoundland are oil workers on their way to Alberta, wearing baseball caps and lumber jackets, with thousands of air miles under their belts. But the Newfoundland of migrant labour and abandoned rural communities is not the Newfoundland that introduces the entertainment programs on the movie screens of these same flights.

The new tourism ads created while Williams was premier offer an “official” version of the place. They rely on two kinds of shots: One is the omniscient aerial views that speed over churning seas and time-lapsed clouds fluttering shadows over the water, then zoom vertiginously toward austere cliff faces, untouched mountains, and fjords. The other is more human in scale: children running in meadows and through clotheslines of brightly coloured laundry, aged fiddlers leaning against freshly painted clapboard. The effect suggests a tourist hurtling from a hectic, harried existence to a slower, more authentic way of being, toward a past that has been perfectly preserved. It’s a gussied-up, coy St. John’s, and a rural Newfoundland that’s self-aware, saturated with unnatural colour. It’s a branded Newfoundland and Labrador, quaint and pleasantly out of sync. There is a virginal innocence, full of grandeur, unsullied by modernity, a past devoid of the shame of poverty or peeling paint. The ads promise more than a beautiful landscape; they promise something felt, a way of life.

And by “way of life,” I mean turns of phrase—my darling, my love, my ducky—vegetable gardens and caved-in root cellars, the glass in the windows of abandoned houses around the bay that has rippled with age, so the world wavers when you glance through it. I mean the reverse bargaining while reaching an agreement over, say, the price of a cord of wood. (Would you give me that for $100? You can have it for nothing. Would you considering taking eighty for it? I wouldn’t consider a penny more than seventy-five.) By the time I was seventeen and graduating from high school, these gestures were already disappearing. The mummers’ parade represents an orchestrated effort to ensure that something of those gestures—particular, vital, and ephemeral—is preserved, even as they alter and morph with each iteration.

Waiting for the mummers to emerge from the fog, I recall an afternoon recently spent in an old converted swimming pool change room that still smelled of chlorine. I was there with my son and a crowd of children, parents, and folklorists who were creating hobby horses for this same parade.

The folk tradition of mummering dates back to England in the Middle Ages. In Newfoundland, the mummers’ play was passed along orally and became a kind of political provocation, satirizing the upper classes. In 1835, when Henry Winton, editor of the local Telegram newspaper, took a negative view of the island’s Catholics in an editorial, he was attacked by a group of masked men. Shortly after, the practice of mummering was outlawed. The plays enjoyed a brief but fiery resurgence in the 1970s, but a decade later they disappeared again, portending the decline that followed the cod moratorium of 1992, which drove a stake through the heart of Newfoundland culture as dramatically as the resettlement programs of the early ’60s did. Without the cod fishery, many outport communities were abandoned. Unemployed fishermen went into retraining programs, or left to find work on the mainland.

Dale Jarvis, a folklorist and the province’s intangible cultural heritage development officer (a title that sounds straight out of an Italo Calvino novel), is one of the instigators behind this latest revival of mummering, and he helped organize the hobby horse workshop. I asked him what the position entails. “I’m an agent provocateur for traditional culture,” he replied. His office works to revitalize aspects of traditional Newfoundland culture that may be under threat.

Ryan Davis, the coordinator of the mummers’ parade, had examined a vintage hobby horse in the Memorial University Folklore and Language Archive, and used it as a model to create something easily producible for the workshop; the original was made of wood and quite heavy. He copied a template of the horse’s head onto sheets of packing cardboard. All over the room, children were bending and folding on the dotted line, slotting flaps, and aiming glue guns. There were bins of fabric and scraps of fur, buckets of wooden jaws, and galvanized nails for the horses’ teeth. The effort reminded me of how quickly the secrets of craftsmanship can disappear. I thought of the many arcane and exacting kinds of knowledge that had once been passed down, from generation to generation, so effortlessly. It seemed Newfoundlanders were born knowing how to build a boat, or fillet a fish with a few economical flicks of the wrist, dance the goat, play the fiddle, or produce a recitation. And I thought about how all of that can be lost within a generation—my parents’ or my own.

“Tradition is always in a state of evolution,” Jarvis said. “Intangible cultural heritage is constantly being reinvented in small communities, giving an old tradition like mummering new meaning and new life.”

My son, Theo Crocker, who is eleven, gave our hobby horse fur ears, a bright red tongue, and giant, startling eyes. He hid under an orange and white checked picnic cloth we had tacked to the horse’s head, so all that showed of him was his sneakers. The horse’s head turned slowly in one direction, then the other. It took in the room and snorted. It clumped forward, pawing the ground with its hoof/sneaker, head swinging menacingly. It nudged my shoulder. Then the jaw crashed shut a few centimetres from my nose. The proper response to such an attack is to thrust a glass of whisky or Purity Syrup under the folds of the picnic cloth and wait for a hand to reappear with an empty glass. All I had was a cup of Tim Hortons coffee.

If these customs and artifacts of the past are ever undergoing reinvention, where does one look, I wondered, when trying to pin down what a place means, or how to describe it at any given point in history? Perhaps the most defining characteristic of life in Newfoundland has been the need to leave coupled with the desire to stay. The habit of travelling to and from the island goes all the way back to the Vikings; settlement was discouraged in Newfoundland until the nineteenth century, and fishermen were expected to leave after the summer catch and return the following spring.

There’s something intrinsically at odds with the excitement and flux of a culture steeped in cosmopolitan travel, rich with the influences of people who come from away, that stands in direct contrast to the notion of the Newfoundland, frozen in time, depicted in the tourism ads. The downtown St. John’s of my youth was a port city full of fishing vessels from Portugal, Russia, Japan, and France, and there were always fishermen off the boats roaming the streets. I remember seeing a group of Russian sailors in the old Arcade store, looking for lingerie to purchase for girlfriends back home. It was an odd sight: groups of burly men digging into big bins, up to their armpits in feminine undergarments, examining the bras they pulled out with mild bafflement. My mother, Elizabeth Moore, says she remembers the Portuguese sailors putting their faces to the windows of downtown houses so they could see the televisions inside: “They were called the White Fleet, because they’d come through the Narrows with the white sails at full mast.” I can also recall the Portuguese sailors playing soccer on the harbourfront, how agile they were, the ball bouncing off their heads, hips, and knees.

The most pressing questions, it seems to me, when thinking about Newfoundland identity, have always been: who arrives, who leaves, and who is altered just by passing through? And, most important, how do all those stories fold together to make a place?

For decades, Gander International Airport served as a convenient refuelling stopover for transatlantic flights. Over time, advances in fuel capacity for jets and airplanes made the international airport redundant, though its unique location became relevant again when thirty-nine planes seeking refuge during 9/11 were grounded there. But back in 1990, it was still used regularly for a fuel stop. That was the year Elena Popova and Luben Boykov, along with thousands of others, defected from Bulgaria. I visit the couple at their home in Torbay to talk about why they chose to settle in Newfoundland. “It was a decision we made for our daughter,” Boykov says.

Popova has just had an exhibit at The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery. The works are giant mixed media pieces, full of colour and kinetic energy. The lines are scrawled, scribbled, gouged, and slashed; the images spark and crack open with light. These are not landscapes, but they evoke the forces of nature: the ocean, wind, and sun. Heat, friction, regeneration, sexual electricity, and tumult are all present. Despite the uncompromised abstraction, there is something of the Newfoundland landscape in them.

The couple’s home is a renovated saltbox. But the word “renovated” doesn’t quite cover it—the original house has been wholly subsumed. I can’t help but see it as a metaphor for their journey, the way distinct cultures can create hybrids that are neither one nor the other, but something entirely new. Here traditional, vernacular Newfoundland architecture meets a bold Bulgarian sensibility. When I ask the couple where the saltbox ends and the rest of the house begins, Boykov tells me, “Elena likes to say we added a coat to the button that was already here.”

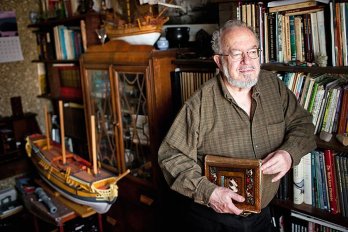

There is a large studio, with walls made almost entirely of glass. One of Boykov’s sculptures, a life-sized figure wrapped in lace, as though mummified, swoops down from the ceiling like an angel or a ghost. The figure has a toy heart that blinks on and off with a bright red light. The dollar store trinket is an ironic reference to something darker: fragility or mortality. The antique lace that wraps the figure is an unexpectedly delicate, feminine material for a man who has built an environmentally friendly foundry to create public sculptures, including commissioned memorials in bronze that capture epic moments of Newfoundland history. Boykov has become a kind of storyteller, working in a medium that is permanent and three-dimensional. The story that brought the family here is just as dramatic.

In early 1990, in communist Bulgaria, the couple, whose daughter Ana was then two years old, heard rumours that some of the planes flying to Cuba for vacations stopped in Canada along the way. “And some of them did not,” Boykov says. “When we got on the plane, we had no way of knowing where we were going. They certainly didn’t tell us.”

They informed their parents and a handful of close friends about their plans to defect, and in February Boykov purchased three tickets for Cuba. After a long, suspenseful flight, the family felt the plane begin its descent. “We looked out the window and saw snow on the ground—that’s how we knew we were in Canada,” Boykov says. Once the plane touched down, they tried to make their way to the front, but they were blocked by members of the crew and told they were betraying the ideals of the communist regime. Boykov punched his way through until he made it to the hatch. When he looked back, he saw that Popova was fighting off a crew member who was struggling to tear their child from her arms. Boykov turned to help her, but she finally managed to break free.

“Once we were out of the plane, we ran,” she says. “There was a Canadian flag at the end of the tarmac, blowing in the breeze, and it was the sweetest sight.” After a brief delay, another two-thirds of the passengers also defected and left the plane en masse.

“Everyone likes to hear the story in the plane,” Popova says. “They like to hear about my bruised arm, how they tried to take my child. I don’t like that story. It’s not an important moment for me.” The best moment for her was the taxi ride to the hotel in a Chevy Caprice: “A great big car, and a little Newfoundland man behind the wheel with a moustache and a big smile. I couldn’t speak English, but I loved the smile,” she says. “The car was sliding through the snow. I can still hear the noise the tires made. And there was Newfoundland fiddle music on the radio.”

Three thousand Bulgarians defected that winter; only thirty or so have stayed in Newfoundland. I ask the couple why they remained. “We were short twenty bucks,” Boykov says, laughing. “There was a subsidized rate at that time for immigrants to travel to Quebec. It was $200. But we were short by twenty bucks.”

A more substantial reason for their staying had to do with a commission for a sculpture Boykov received two years after they arrived, an offer to create a memorial in the town of St. Lawrence. The sculpture, with its $100,000 fee, would celebrate the bravery of the men of St. Lawrence who risked their lives to save the drowning soldiers from two sinking naval vessels that ran aground in a powerful storm during the Second World War. That sculpture was the beginning of the family’s commitment to the place and a way of life. “Newfoundlanders trusted me, an outsider, to tell their stories,” Boykov says. “It is a remarkable thing.”

If Boykov and Popova are an example of those who come from away and enrich Newfoundland with fresh aesthetic insights, Stephen Lewis represents the Newfoundlander who has looked for training on the mainland and returned, bringing with him a fresh breeze of entrepreneurship. Lewis is co-owner, along with his wife, Emily Sopkowe, of the small business success story that is the Georgetown Bakery in St. John’s. He invited me to come at six o’clock in the morning to see how the bakery operates.

It was cold and dark when I set out through the streets of downtown. The closed sign was hanging in the window, but when I tried the door it opened, and a tiny bell on the door frame tinkled. Lewis was already at work with two other bakers in the small kitchen. Clouds of flour floated in the air, along with the sweet smell of baking bread. I asked him how he decided to become a baker.

After earning a degree in philosophy and making a failed attempt at farming, he became interested in baking when a friend in Montreal taught him how to make a loaf of bread in his own kitchen. He then embarked on a six-year apprenticeship in a variety of bakeries around the city. In 2002, he and Sopkowe decided to return to Newfoundland with their first child and open a business of their own, but they immediately faced what Lewis calls a steep learning curve.

“By the time we were ready to open, we were out of money,” he says. “We’d spent everything on setting up, and our credit cards were maxed out. We had just one bag of flour, but we decided to take a trial run.” The bakery sold out over the course of that first morning. With the profits, he bought another bag of flour that afternoon. Their business doubled on a daily basis for the first few months of production, with Lewis working all night, six nights a week, to keep up with the demand.

“Flour power, Steve,” says Gary Cogswell, one of the bakers working alongside him, who came to Newfoundland from Port Hawkesbury, Cape Breton. “I’ve been here fourteen years. I consider myself a Newfoundlander.” I ask him what brought him to St. John’s. “The ferry,” he says, “and now I’m rolling in dough.”

The Georgetown Bakery is crowded most mornings. Its success can be attributed as much to Lewis’s demeanour as to the Montreal-style bagels. Lewis has a gruff, no-nonsense warmth and integrity that characterize the simplicity of the bakery’s interior: a plain wooden counter and shelves for the bread, a few toys and newspapers on the window bench, a fresh pot of coffee. Customers often find themselves pressed against each other, shoulder to shoulder in the sweet-smelling heat, the cash register hammering on without pause.

“Big-city neighbourhoods have local bakeries,” Lewis says. “It’s a part of the modern urban experience. People here want to experience that.” He deliberately keeps prices low, to attract people from the neighbourhood, but customers drive from all over the city for his bread, arriving in time to get it fresh from the oven.

Lewis and his wife, who is originally from northern Manitoba, via Ontario, have had two more children since they returned to Newfoundland; and besides taking care of the business end of the bakery, Sopkowe has renovated their heritage home. The couple plans to stay for a while. I ask Lewis why he came home. “The main reason was Emily. She had come for a visit and decided that St. John’s was where it was at. I said, ‘Well, you’ll get no argument from me.’”

While people like Lewis and Sopkowe returned to Newfoundland to be near family and the vibrant artistic community, many of the province’s writers, artists, actors, and academics leave to seek wider audiences, or to explore new influences. Author Wayne Johnston has said that he can only write about Newfoundland when he is living away from the island. He, along with writers Michael Winter and Kathleen Winter, artist David Blackwood, and comedians Rick Mercer and Cathy Jones—to name just a few—have created some of the most vivid and lasting depictions of Newfoundland culture, all from the distance of the mainland.

I had arranged to meet Rick Rennie, a researcher with the Workers Compensation Board of Manitoba, for a drink while I was on a reading tour in Manitoba, but we had missed each other. Instead, we caught up on the phone.

“I grew up in Little St. Lawrence,” he says. “Men could basically do one of three things: there was the mine, you could go into the fishery, or you could go away for work.” He holds a doctorate in history from Memorial University and has written extensively about labour. His 2008 book, The Dirt, is a damning critique of industrial disease, and the corporate neglect that led to the deaths of some 200 miners in St. Lawrence. Like others before him, he left home for employment opportunities, and moved to Winnipeg eight years ago with his wife, Ingrid Botting, who is from there.

“People went away in my family ever since I can remember. There was a sense of adventure about it; they were having fun, a rite of passage.” He is one of thirteen siblings, all of whom but one sister left Newfoundland for work on the mainland. “In my family and on that part of the coast, many people migrated to the Boston States—that’s what Newfoundlanders called New England—part of a migration that began in the nineteenth century,” he says.

As a child, he remembers his family receiving care packages from distant cousins in the United States. “We called it the barrel,” he says. It was a custom for relatives living away to send second-hand clothes and little toys back home, though it probably wasn’t an economically feasible proposition, considering the postage. “There’s a photograph of ten of us, outside our house one day when the barrel arrived. There we are in our bell-bottoms and garishly coloured ties, decked out in all the new clothes. We were so proud of it, we put it all on and had to go outside the house to get our picture taken.”

Rennie still comes home, every summer, to see the old house where he grew up and to visit with siblings who also return. The community has become dormant since the mines closed. “There’s nothing going on in that place. But every year, something tugs us back there. We could get together somewhere else. We could have guaranteed two weeks of sunshine at an Ontario cottage if we wanted, but for some reason we tend to go back to Little St. Lawrence.” But he is careful to guard against an illusory romanticism about outport life.

“I am not one of those Newfoundlanders that pines to live in Newfoundland,” he says. “I love visiting my daughter and my friends in St. John’s, but I honestly never have a desire to stay. I have a nice life here in Manitoba. Our boys have grown up here and have family and friends here. Ingrid is happy and has a good career here. All of those things are very important.”

Like Little St. Lawrence, many rural communities have lost most of the working-age population; the old saltbox houses have decayed and settled into the earth. Graveyards in some communities have been all but devoured by the ground, the tombstones eroded by weather, the graves themselves sunken or entirely lost. Valuable coastal property has been purchased over the Internet by foreign investors. Yet in major centres across Canada, you don’t have to look far to discover a Newfoundland pub or find Newfoundlanders gathering for Jiggs’ dinner, returning from visits home with partridgeberry or bakeapple jam, or jars of moose or caribou.

“I have one brother who goes back to Newfoundland rarely, but he’s the one who talks about it the most,” Rennie says. “We call it the ‘time machine.’ It’s easier to maintain the illusion of a romantic Newfoundland if you don’t go there. If you think of it as a time rather than a place, it’s true that you can’t go home again.”

There have been some travellers who have changed Newfoundland by simply passing through. In the winter of 1942, two American naval vessels, the Truxtun and the Pollux, ran aground in a violent storm off the coast of St. Lawrence. The Truxtun began to sink, and the men were forced to jump overboard into a frigid, storm-tossed sea, and a spill of crude oil pouring from the damaged ship. The forty-six who made it to shore—of the 156 on board—were the only survivors, and had nearly frozen to death in the water. In a heroic effort, the people of St. Lawrence risked their own lives to perform a daring rescue.

One of the sailors who escaped the wreck was Lanier Phillips, an African American from Georgia and the only black man to survive the disaster. He was taken to a temporary first aid station, where the women of the community were nursing the survivors. He had passed out and woken up, naked, on a table, in the company of two white women who were washing the oil from his skin.

As the great-grandson of slaves and a black man who had grown up in the American South during the Jim Crow era, he was terrified to find himself naked in the presence of white women. Then he discovered that one of them, Mrs. Violet Pike, was trying to wash the pigment from his skin. She had never seen a black man before and had assumed the oil from the spill had seeped into his pores, and she was determined to get him clean.

Robert Chafe, a recent recipient of a Governor General’s Award for playwriting, depicts Phillips’ life in a powerful and harrowing new work called Oil and Water, produced by the Newfoundland theatre company Artistic Fraud and directed by Jillian Keiley. With uncanny grace and devastating simplicity, Chafe portrays the moment when Phillips wakes up, a scene full of baptismal symbolism: rebirth and innocence.

Phillips (Ryan Field) says, “That’s my natural colour.” Pike (Petrina Bromley) holds out his hand before her and stares at it for a brief moment, dumbfounded. Then she speaks with the quiet astonishment of discovery: “Is it? It’s beautiful. The colour of deep water—not tar at all. I sees myself, now that I’m looking.”

Chafe tells me he first became interested in the story of Phillips in 1996 when he saw a painting by Newfoundlander Grant Boland titled Incident at St. Lawrence. Over the years, the tale had gained the shimmering aura of an urban legend. And when Chafe began researching Phillips’ account of the journey, he saw in Pike something of his own grandmother’s story, and that of many Newfoundland women from her generation.

“My grandmother Hazel Chafe had spent all her life, quite contentedly, in Petty Harbour, living what most people would call a sheltered existence. She would have been in her seventies when cable television arrived in Newfoundland. Like Violet Pike, her world was her community,” he says. “Sometimes people assume isolation of that sort leads to xenophobia or a fear of the new—but it is the kindness of these women that is so touching. Lanier Phillips talks about that moment as one of pure goodness and innocence, a moment of great humanity.”

In a powerful radio documentary produced in 2000 by Chris Brookes, Phillips says that not a single day goes by when he doesn’t think of the kind treatment he received in St. Lawrence: “They changed my entire philosophy of life.” Returning to the United States, he became a civil rights activist, fighting for desegregation and equal opportunity for blacks, particularly within the armed forces.

I ask Chafe what the story says about Newfoundland.

“I remember when I was nine or ten years old,” he says, “I saw the first battle I can remember about the seal hunt on the news. The portrayal of Newfoundlanders by the media and by Greenpeace was very negative. I remember the way people were speaking about us. For a long time here in Newfoundland, the Lanier Phillips story was viewed as a kind of Newfie joke. How could these Newfoundlanders not know there were black people in the world? It was only when Lanier came back decades later to say how a two-day experience here had changed his life that we saw the meaning of the story. That’s what moved me. This man encountered a Newfoundland that many Newfoundlanders know and love. He recontextualized the story—and not only for Newfoundlanders, but the world.”

Over the past decade, Newfoundland has seen an influx of immigrants from Sudan and other parts of Africa. My son has been close friends with a child from Liberia, the daughter of our back fence neighbour, since he was five. One day, she brought a child from Sudan over to our house to play, and I offered the kids grilled cheese sandwiches. The new child answered with an accent that I recognized right away as being from the east end of St. John’s: “No tanks, missus, I don’t want none of dat.” It was an accent more pronounced and perfect than my own, and I envied it.

It strikes me that the recontextualization of the story Chafe relates is very similar to the rescuing of tradition to which Dale Jarvis referred: They hold a mirror, or a hall of mirrors, to the culture in Newfoundland. They provide ways of seeing Newfoundland anew.

Standing on the sidewalk, waiting for the mummers’ parade, my husband and I talk about what Danny Williams has done with Newfoundland nationalism, a force behind much of this reconstitution of identity, especially as it occurred in the ’70s, and again now with the influx of oil wealth.

“Culturally, I think Williams represented an important turn in the oppositional character of Newfoundland culture,” Steve says. “During his reign, all the rhetoric of Newfoundland nationalism was made into a mainstream political science discourse. Now you could be a Republican and understand that to be a rather bland financial problem of transfer payments and constitutional law.”

He points out that Brian Peckford, who was premier in the ’80s, also made use of Newfoundland nationalism, but he recognized it as something outside the state that the state worked in the service of. He famously said, “One day, the sun will shine, and ‘have-not’ will be no more.” The “have-not” he invoked defined itself in opposition to established power.

“Danny measured progress in financial terms: royalty regimes, transfer payments,” Steve says. “Of course, all of that is hugely important, but only if the financial program is coupled to a wider social plan. The benefits of oil are unevenly distributed, so outside the overpass the consequences of Danny’s war mean less.”

I ask what he thinks of Williams’ wild popularity.

“It’s odd that people considered Williams a man of the people,” he says. “They loved him, but he was remote. He was fiery in press conferences, but you did not see him talking to people or taking up particular problems, or having Jiggs’ dinner or anything like that—which Brian Tobin, for instance, often did. He was not out in the streets. Maybe no one is now.”

Then a figure appears in the fog, a man in petticoats with a lace veil over his face. There is a galloping cavalcade of hobby horses, tattered blankets, wedding veils, and sou’westers. Men are wearing giant brassieres over their oil slicks; women are in lumber jackets, one or two with their faces blackened.

One mummer has a cardboard replica of the Matthew on his head; another has a clothesline propped on his shoulders, with underwear of all sorts swinging from it; gender is upturned in the typical mummer’s costume, everything masked and subversive, the world gone topsy-turvy. Someone is playing a bodhran, and the wild beat of it thrums through the soles of my boots. There’s a man wearing swimming goggles, a snorkel, and a frilly apron. Several people pass by with crocheted doilies pinned over their faces. They are dancing and twirling and banging ugly sticks, skipping and stamping and rough-housing in the streets.

This appeared in the May 2011 issue.