Not long after he was elected prime minister in 1968, Pierre Trudeau invited two dozen of the country’s top artists to dinner. The occasion was no photo op; he wanted to hear their views on national identity. Canada had just celebrated its centennial, and the new leader was intensely aware of the ongoing need to hone a shared identity. Among the painters, musicians, and writers was architect Arthur Erickson, and this first meeting would mark the beginning of a long and influential friendship with the prime minister. As David Stouck recounts in a new biography, Arthur Erickson: An Architect’s Life, “The gesture of a politician turning to artists for advice seemed extraordinary, and Arthur’s meeting with Trudeau was one of instant rapport.”

Stouck confirms that Trudeau’s subsequent championing of Erickson was no accident. Rather, it was a sign of the times—an era, very different from our own, in which politics and the arts coexisted. The seeds had been planted in 1949, when the Massey Commission launched a two-year study on the state of the arts in Canada, concluding that government support could provide a bulwark against American assimilation. The first Massey Medals for Architecture, awarded in 1950, helped to redefine Canadian architecture as a cultural industry. No longer were architects perceived as mere contractors-cum-decorators; now they became nation builders. All of those interlocking cedar beams, sheets of glass, and reflecting pools seemed like a pretty good expression of the idea of Canada.

While Erickson was the only architect at Trudeau’s dinner, he was not the only architect helping to shape the country’s modern identity. Fellow Vancouverite Ron Thom was, as well as his contemporary, in many ways his architectural counterpart, designing beautiful enclaves while Erickson created beautiful expanses of space. Today, a few years after Erickson’s death and more than a quarter century after Thom’s, the two architects have once again achieved a national presence. Tributes to Thom are in the works, as two of his finest commissions, Massey College and Trent University, celebrate their fiftieth anniversaries. The publication of Stouck’s biography of Thom’s long-time rival is a karmic coincidence (the book was to have made its way into stores last year but was delayed when the publisher changed hands).

Erickson and thom were among the lucky architects who started their careers in the wave of postwar optimism. On the West Coast, land was plentiful and cheap, and young architects could experiment at will. Armed with talent and polished social skills, Erickson received residential commissions from clients who seemed not to mind the often-leaky results. His early partnership with Geoffrey Massey (the nephew of the first Canadian-born Governor General, Vincent Massey) evolved into a deep, symbiotic friendship and facilitated his idiosyncratic practice. Stouck conveys the essence of their collaboration in a single anecdote. During the construction of Simon Fraser University, in the early ’60s, it came to light that one of the concrete slabs was too thin to bear the weight required of it. “Geoff burned up the telephone lines, shouting at various contractors and suppliers to deal with the problem at once,” writes Stouck. “Simultaneously, Arthur was on another line trying to track down a certain kind of gold-scaled koi for a reflecting pool.”

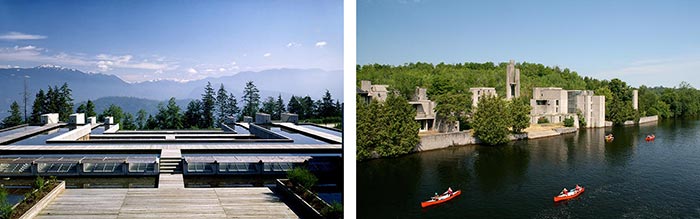

Simon Fraser was Erickson’s first major institutional project. Situated on Burnaby Mountain in suburban Vancouver, it reads as a sleekly modern quadrangle that crowns the mountaintop like a regional logo. In keeping with the age, it broke ground architecturally and programmatically, its science and humanities departments configured to foster a literal crossing of paths. The professor of biochemistry would rub shoulders with the professor of nineteenth-century poetry, perhaps gleaning an unexpected insight into nucleotides during an impromptu chat about anapests. The future, it seemed, belonged to interdisciplinary studies, and architects like Erickson were the social engineers who could make it happen.

That an architect even registered on the collective consciousness is the envy of modern-day practitioners, whose work on even the most important institutions is so often marginalized and anonymous. Back then, however, top-tier architects marched in lockstep with other social activists, enacting change rather than reacting to it. Erickson created a panoply of instant cultural landmarks, among them the Smith House, Simon Fraser, the Law Courts, and the Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver; the University of Lethbridge in Alberta; Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto; and a cache of sleek buildings in California. He liked to dissolve barriers, designing adjacent rooms as continuous open spaces, and using expanses of clear glass, even in the Law Court offices. Stouck’s description of his epic and highly entertaining personal history, from his intellectual camaraderie with Trudeau to his extravagant Los Angeles soirées (he liked parties, especially big ones), shows how his life and work fuelled each other. In his work, you can read his life: Erickson as thinker, traveller, bon vivant, social climber, groundbreaker.

In the ’60s, his sexual orientation was not only potentially scandalous; under Canadian law, homosexuality was still a crime. According to Stouck, the fact that Trudeau, Erickson’s close friend, decriminalized homosexuality might have been no coincidence, although he stickhandles around the precise nature of their friendship, long the subject of backroom chatter. “Arthur was aware of the rumour that Pierre was gay and that this had made the former prime minister, Lester Pearson, uneasy about his successor,” writes Stouck. “The close friendship between prime minister and architect fed the public perception that the prime minister needed a wife.” Stouck suggests that Trudeau’s abrupt marriage to the young Margaret Sinclair was intended, at least partly, to quell the rumours. Erickson contented himself with a commission to redecorate the prime minister’s office, and, years later, to design the Canadian chancery in Washington, DC, despite howls of outrage from politicians and fellow architects.

The cronyism infuriated many in the Canadian design community, and their anger was only exacerbated by Erickson’s by now notorious extravagance. The most famous architect in Canada began to experience trouble procuring work. Stouck reports that in the early ’80s, after Erickson lost the bid to design Canada Place, Vancouver’s federally funded waterfront convention centre, he wrote to Trudeau asking him to intervene—but this time, the prime minister stayed out of it. “Friends and associates were beginning to feel that Arthur had made something like a Faustian bargain,” writes Stouck, “selling himself to get the chancery [in Washington], with everything afterwards turning to ashes.”

Meanwhile, the interdisciplinary mash-up at Simon Fraser had not turned out the way its creators had envisioned. Instead, by the late ’60s the university had become a hotbed of social dissent. As Stouck tells it, “SFU was dubbed the Berkeley of the north. The campus seethed with unrest. The question arose: what role did the architecture play in this upheaval? ” When Shell Canada decided to build a service station on the campus, students led a protest that, as Stouck reports, put a spotlight on the architecture; first, because corporate Canada was made to feel unwelcome on this beautiful and precisely designed campus; and second, because Erickson’s huge open quadrangle had made it easier for disaffected students to meet, mingle, and rise up. Traditionalists pointed to the architecture with derision, although Erickson took this as a sign that it worked.

As construction of Simon Fraser got under way, another new and idealistic university on the other side of the country was admitting its first students. Trent University, on the outskirts of Peterborough, Ontario, was the creation of Ron Thom, Erickson’s former colleague at the sizable Vancouver firm that became Thompson, Berwick & Pratt. He, too, was famous and touted as the great Canadian architect, although in their work and personal lives the two could hardly have been more different. The sometimes rumpled, hard-drinking Thom projected an equally strong but strikingly different charisma: if Erickson was architecture’s William Wordsworth, Thom was its Dylan Thomas. Unlike Erickson, Thom rarely travelled and was more inclined to hang out with his art school chums and lesser-known clients than with celebrities. In contrast to Erickson’s philosophic rationalizing, Thom would feel his way around a design scheme, using intuition to guide him. They became known respectively as the thinker and the feeler, or, as their one-time boss Ned Pratt put it, Erickson was “neck up,” Thom “neck down.”

Thom had trained at the Vancouver School of Art, and inclined more to the persona of introspective artist. His West Coast houses were given not to dance floors but to dens: cloistered dwellings with sloping ceilings that sometimes grazed the heads of their occupants. He, too, created an array of cultural landmarks, but his were inward looking: Massey College in Toronto; the Shaw Festival Theatre in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario; the Toronto Zoo. His thick, fortress-like walls and steeply pitched ceilings cosset their inhabitants: in a Ron Thom building, you feel protected from the outside world.

So it was with Trent, where Champlain College, its flagship, was devised as a radically new kind of post-secondary institution: an all-in-one building where students could study in small catch-all rooms at the ends of residential hallways instead of being poured into grandiose amphitheatres. As at Simon Fraser, Trent’s design and programming were intended to foster the integration of the various fields of study. (Once again, the plan didn’t work out; its champion, founding president Thomas Symons, left his post in the early ’70s, and then years of massive shortages in government funding obliterated what remained of the original ideal.) Unlike Simon Fraser and Lethbridge Universities, which can be seen from kilometres away, Trent is barely visible, unless you make a point of seeking it out. As with a geode, the drama mostly transpires inside, with light seeping into cavernous rooms through high windows.

In 1960, both Thom and Erickson, along with two other architects, had been shortlisted to design Massey College, a graduate student residence and haven for scholars on the University of Toronto’s busy campus. According to Thom’s biographer, Douglas Shadbolt, Erickson would later say that “Ron copied my plan, i.e., the concept.” Erickson claimed that he and Thom had made a pact to show each other their initial entries, expecting them to be final. As it turned out, though, there was a second round, in which both architects submitted revised plans, and which Thom won with a brilliantly modern evocation of an Oxbridge college.

Erickson’s complaint, which Shadbolt’s biography Ron Thom: The Shaping of an Architect systematically dismantles, hints not only at their rivalry but at the uniqueness of the project. The project was bankrolled by the Massey Foundation, which was headed by Vincent Massey, and boasted three of his kin on its selection committee: son Lionel, who soon became a director of the Royal Ontario Museum; son Hart, a Toronto architect; and nephew Geoff, also an architect and Erickson’s future business partner. (Canada’s architectural community was, and still is, a village.) The design memorandum, which stressed the need for “intimacy” and “dignity, grace, beauty and warmth,” spoke to the introspection of the Canadian persona. On Thom’s copy, four of the five words are circled repeatedly in pencil. Dignity, grace, beauty, warmth: these are the qualities one finds in a haven, and havens were his thing. When Massey College opened in 1963, with Vincent Massey presiding, it was a defining moment for Thom and, no less, for Canadian architecture.

The lives and fortunes of Erickson and Thom nosedived at around the same time. Thom’s lifelong struggle with alcoholism grew more intense, and he was near bankruptcy when in 1986 he shut himself in his Toronto office, inebriated, and died at his desk. He was sixty-three. Erickson, meanwhile, won no significant commissions at Expo 86, even though it took place in his hometown. His reputation for profligacy, which Stouck largely attributes to the expensive tastes of Francisco Kripacz, his life partner, alarmed both his employees and his business partners. The upshot, writes Stouck, was that “Canada’s great architect—a handsome, elegant man who counted among his close friends Pierre Trudeau and Elizabeth Taylor—eventually became penniless.” Plagued by health and financial worries, Kripacz committed suicide in 2000, an event Stouck’s book recounts powerfully in Erickson’s own words. When Erickson himself died in 2009, Vancouver’s arts establishment thronged to his memorial service in Simon Fraser’s quadrangle.

However tragic their final years, Erickson and Thom remain the most celebrated architects in Canadian history. The University of British Columbia has launched a perennial Arthur Erickson lecture series; the Arthur Erickson Foundation plans to restore his Vancouver house and garden; and yet another book about Erickson, by Texas-based academic Michelangelo Sabatino, will be published in 2015. The Canada Council for the Arts’ Ronald J. Thom Award for Early Design Achievement is now in its fourteenth year; and the Toronto architecture firm Shim-Sutcliffe has for many years been refining, adjusting, and updating Massey College, helping it earn both the Prix du XXe siècle from the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada and the Ontario Association of Architects Landmark Award in 2013. All that, for two West Coast idealists who seduced the country’s leaders into believing that architecture could shape and define it—and they might have been right.

This appeared in the November 2013 issue.