Picture her life, starting in the Depression. My mother is born in the 1930s to a working-class immigrant family living in Toronto. Her father is a foreman at Casselman’s Wiping Cloths Company, and the couple has three children: two cherished boys and one perhaps not-as-cherished girl. Her name? Diane Hutchings. Not worth a middle name.

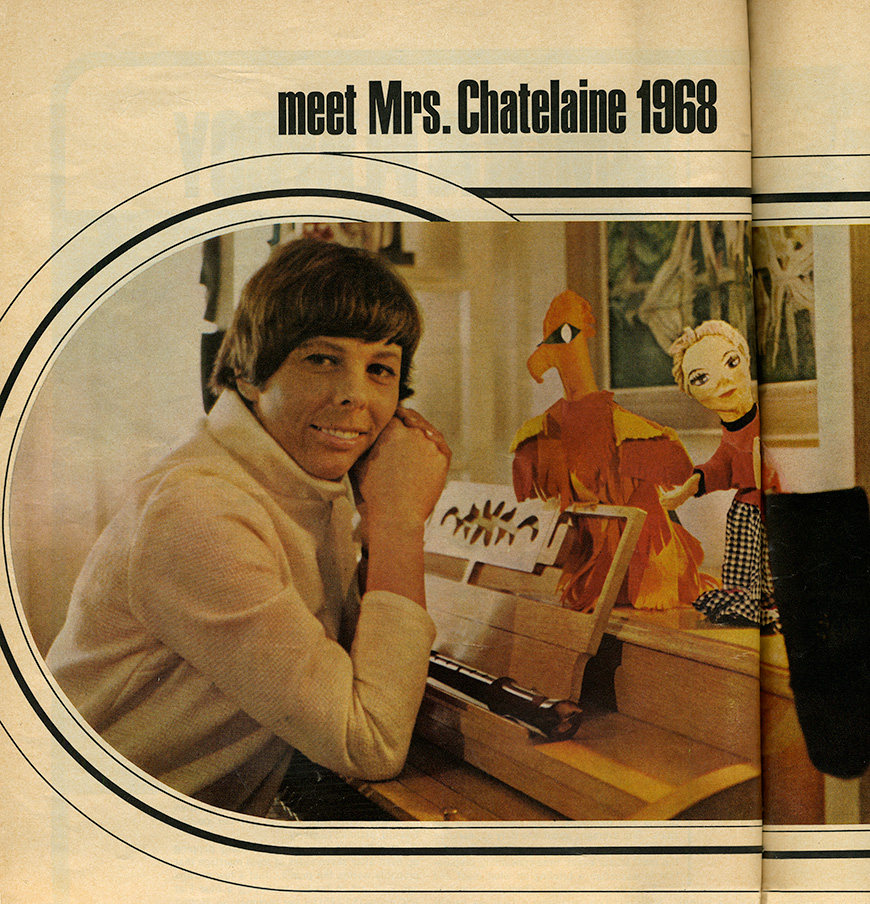

Diane gets her high school diploma, teacher’s certificate, marriage certificate. But, in the early 1960s, marriage leaves her isolated in a Richmond Hill bungalow. She lacks confidence, but she’s a natural creative. She paints, presses flowers, and pens poems—and she teaches her students to be creatives too. A few years later, in 1968, she would win the Mrs. Chatelaine title, an award bestowed by the women’s magazine on the best Canadian homemakers. That would give her a dishwasher and a fleeting belief in herself.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

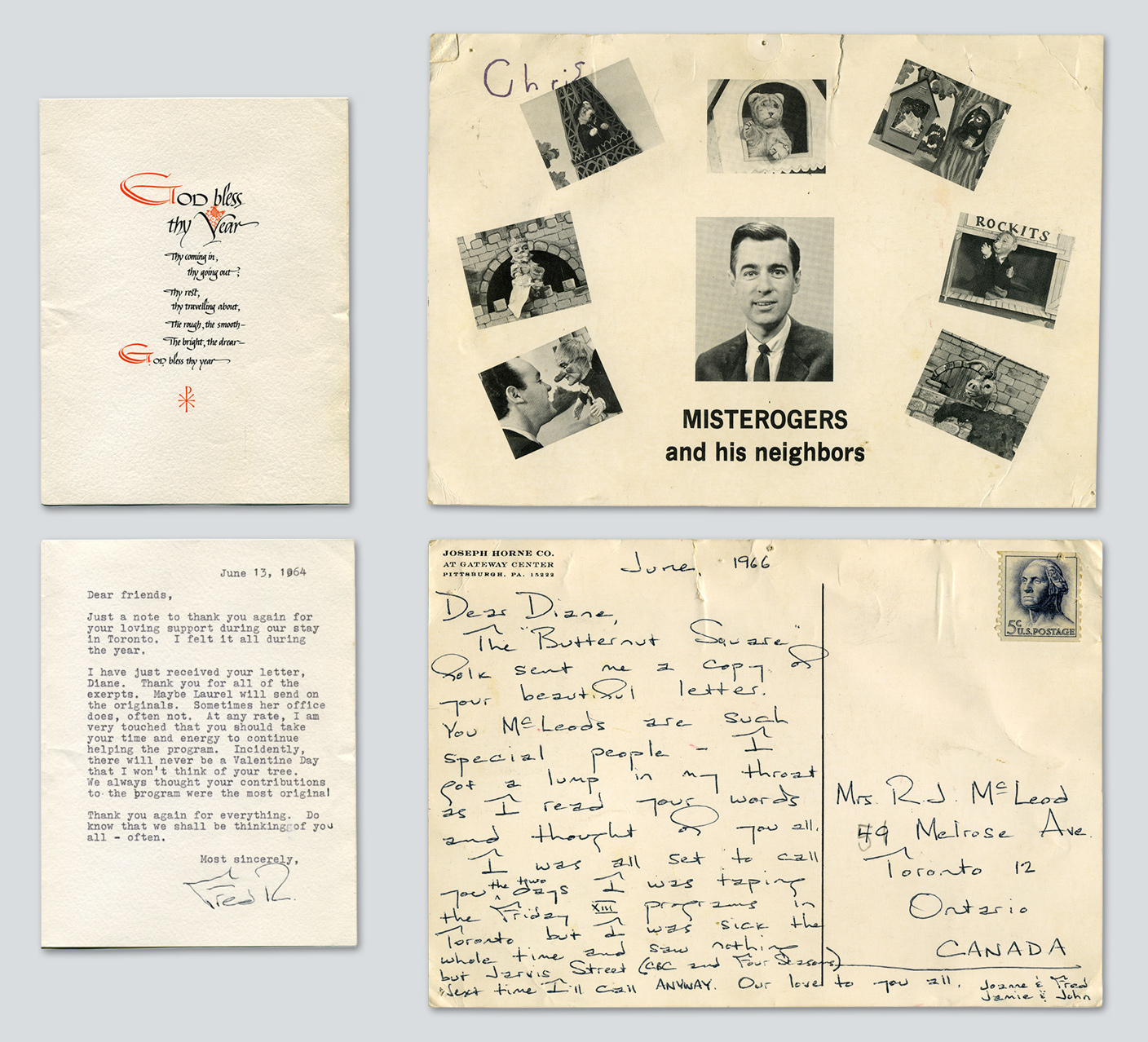

In 1963, Mum, my young siblings, and I sit at the table with paper and crayons, watching the CBC—and that’s when we encounter Fred Rogers. The network invited the young American, who had worked on a local children’s show in Pittsburgh, to create a new kids program in Canada. Mum describes the segment, featuring Mister Rogers and his land of make-believe, as different from anything she’d seen. “Fred was so quick to pick up on how bad things could become good things for children, no matter what challenges they faced. It was a message I needed to hear too.” Then, one day, the show’s not there. She writes to the CBC and gives the broadcaster hell.

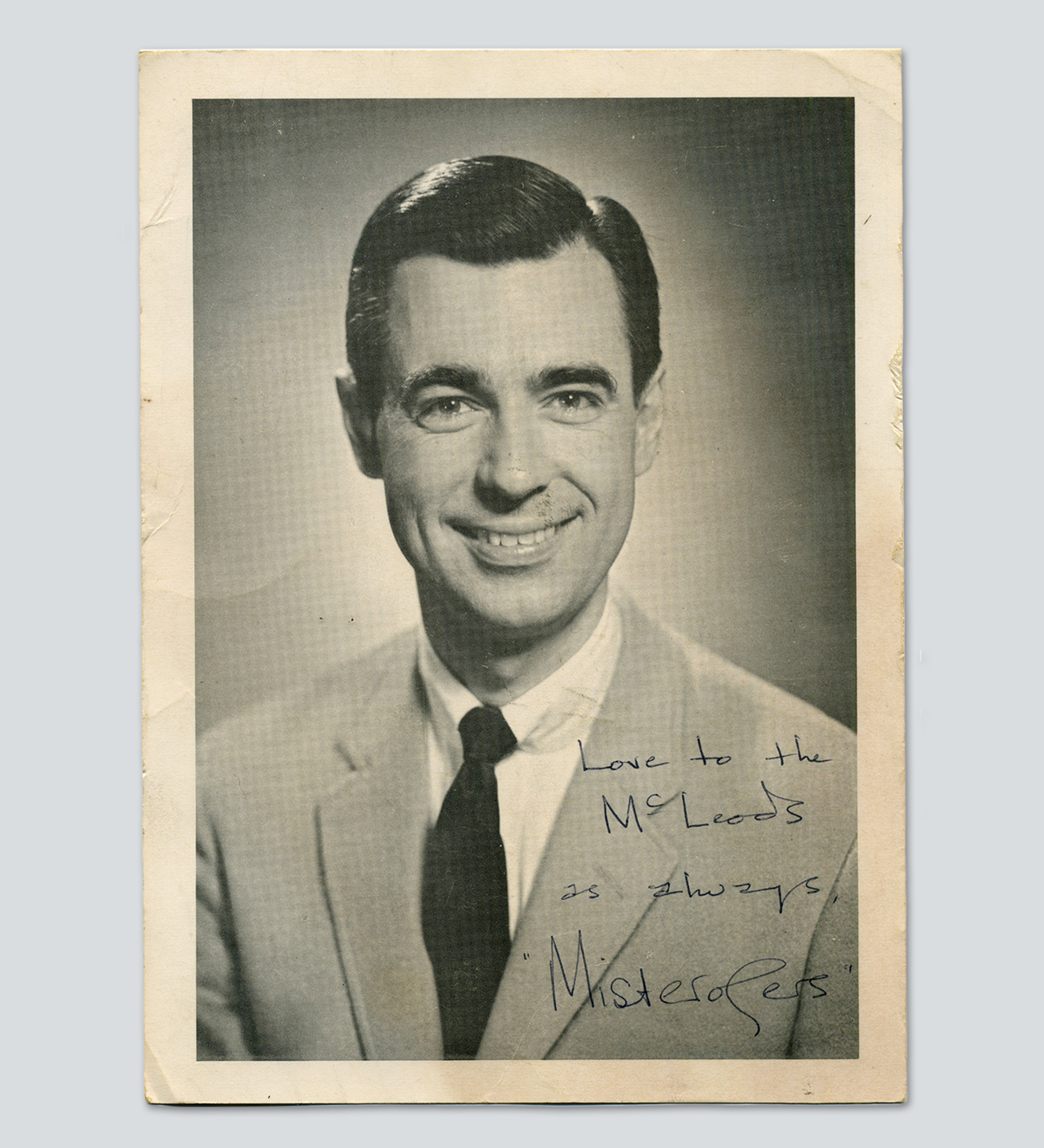

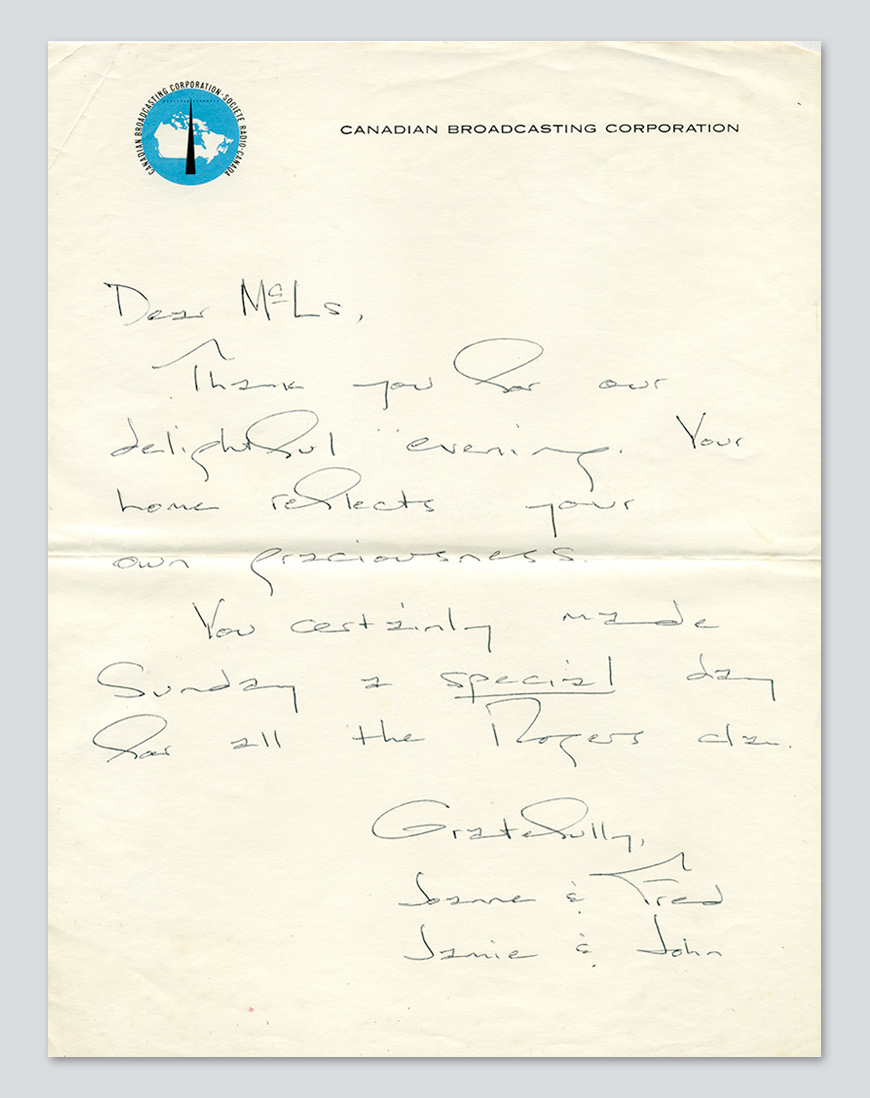

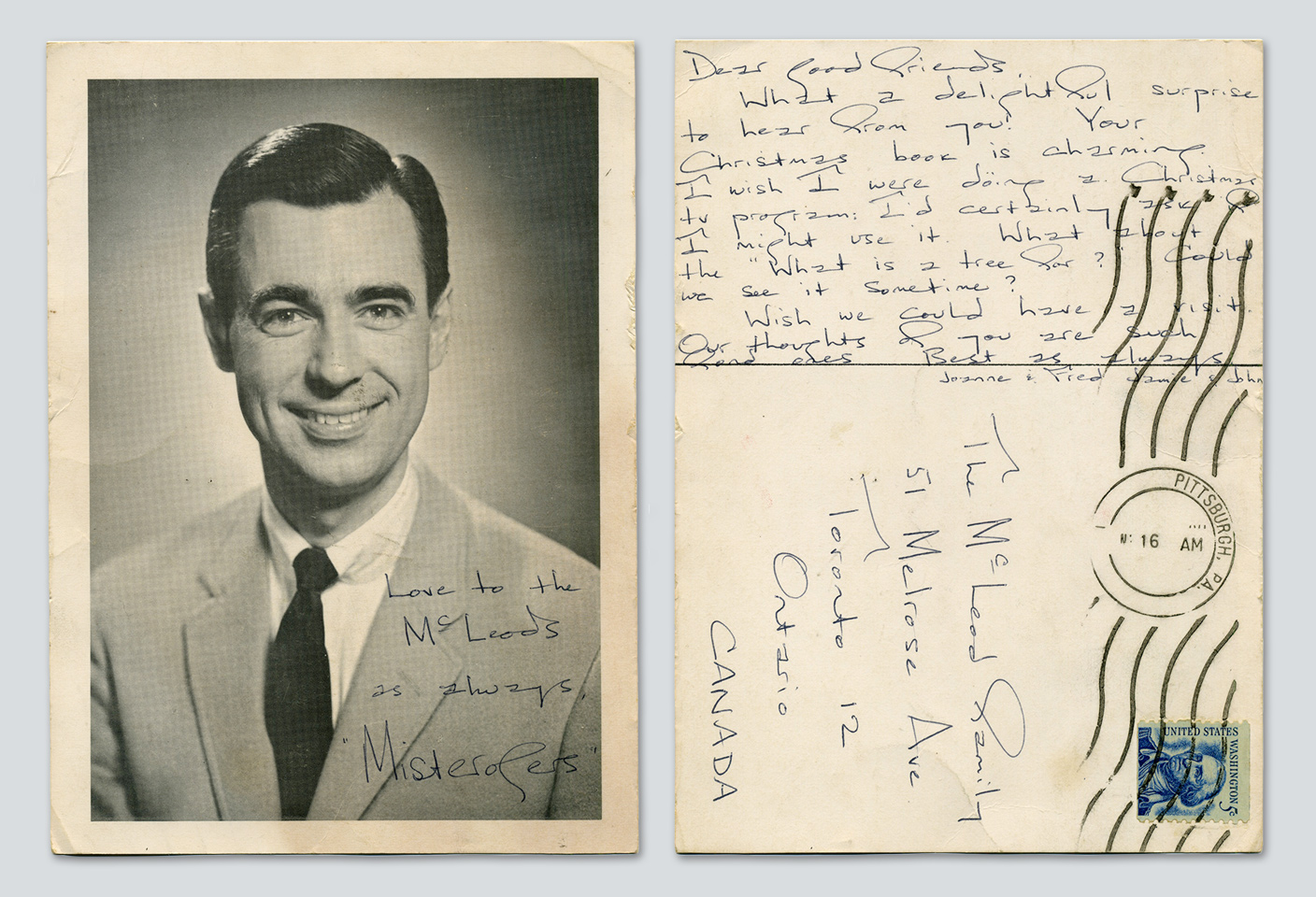

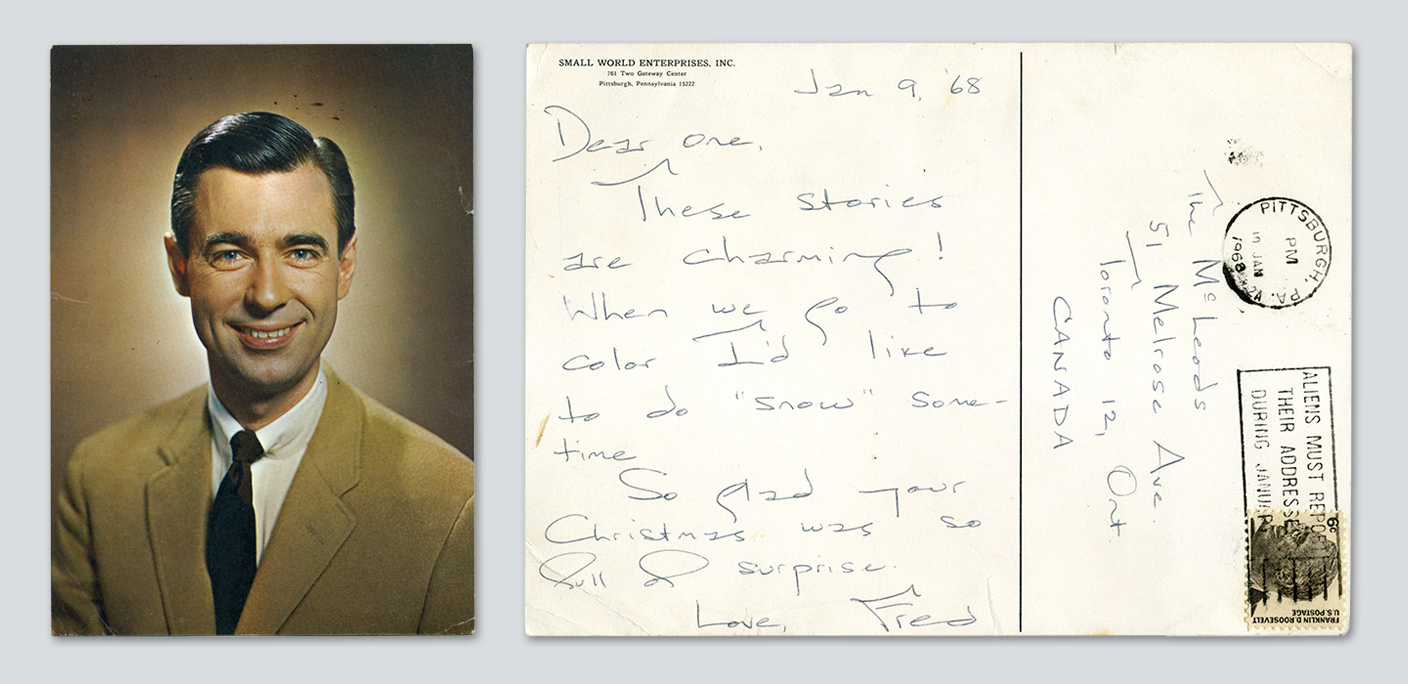

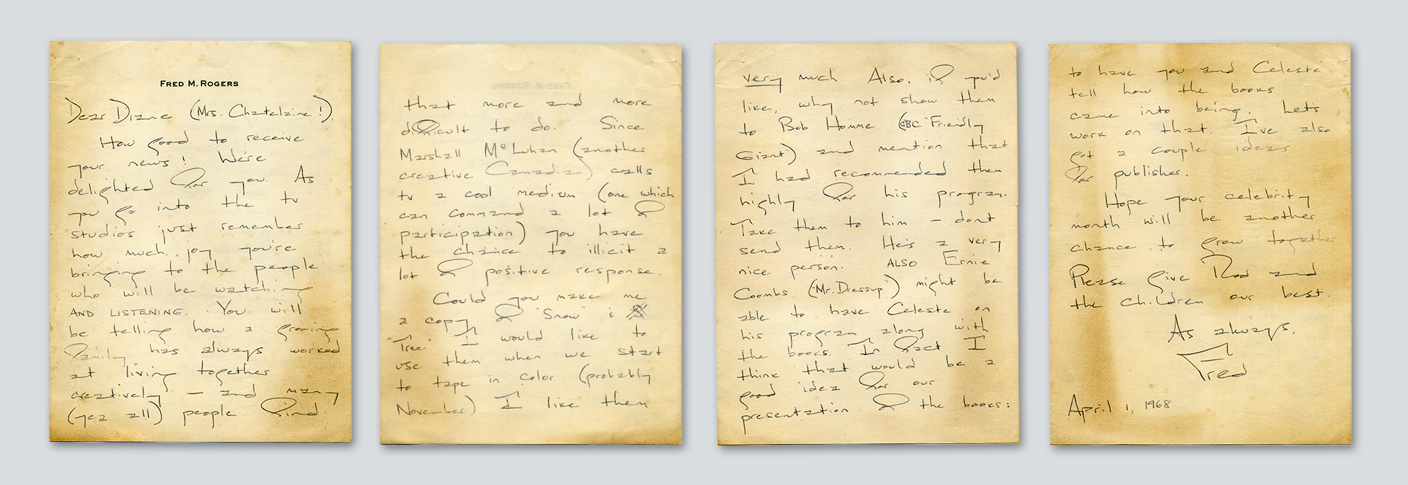

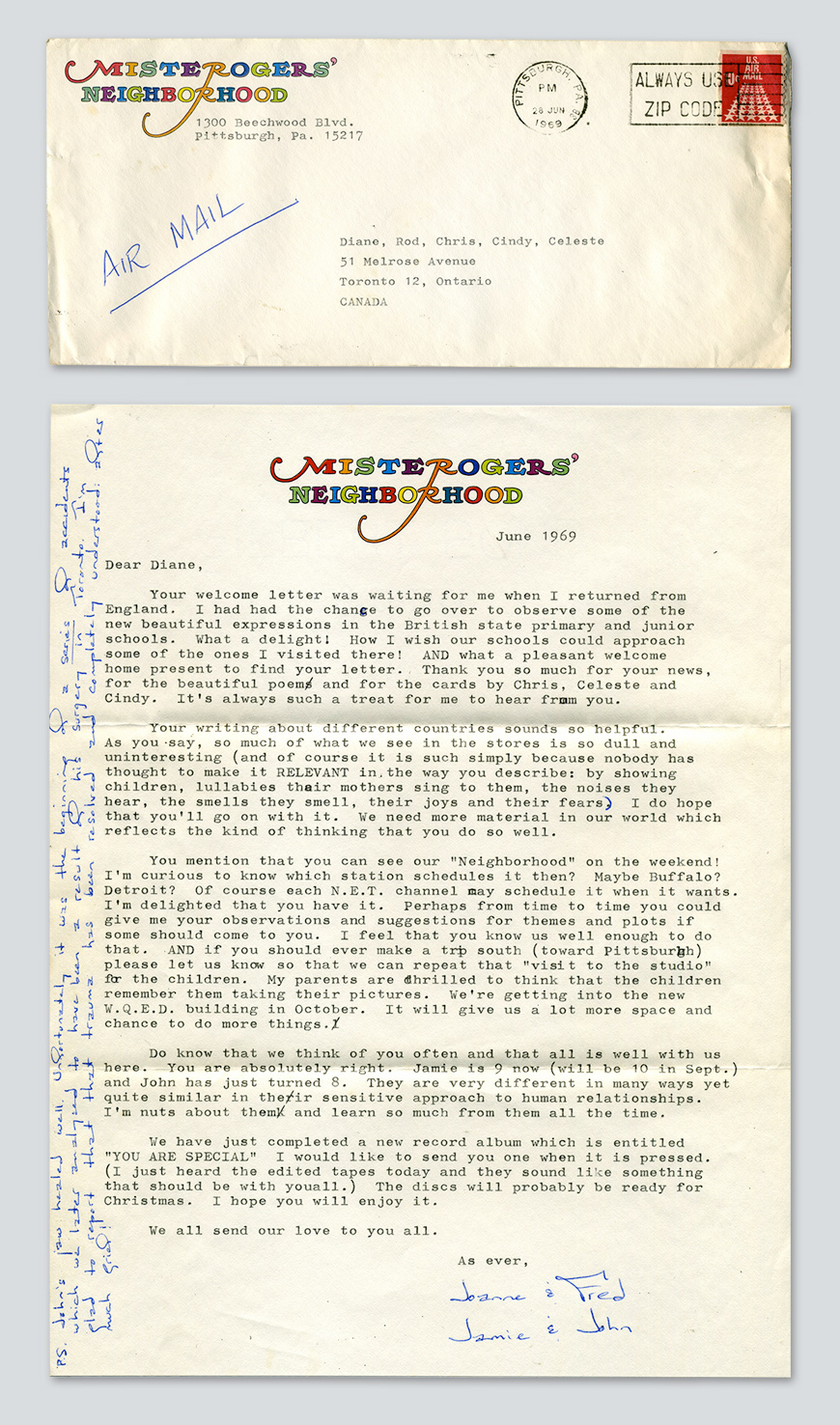

Mum remembers Rogers writing back: he’ll return after Christmas. And so begins years of correspondence and collaboration. Soon, he invites us all to his CBC set. Mum also shows him her unpublished children’s books: What’s a Tree For?, What’s the Snow For?, What’s a Friend For?, etc. In one letter, he asks for copies: “I would like to use them when we start to tape in color (probably November). I liked them very much. . . . I’ve also got a couple ideas for publishers.”

I didn’t know about the letters until I visited Mum in her retirement-home apartment this February and she mentioned she couldn’t find them. I remembered the studio visits, but I didn’t know that they’d continued to keep in touch.

I searched her closet and, in a box marked “keepers,” found some survivors. A few weeks after that, the pandemic took hold and I could no longer visit. Most of our prepandemic phone calls had relied on me carrying the conversation with good news, but now there wasn’t much to share. Instead, I crafted questions about her friendship with Mister Rogers before our calls, then methodically asked them until she tired. There were some lonely days for her in lockdown. But I’d hear a change in her voice whenever I mentioned Rogers. He was the man who had recognized her, and her daughter wanted to know that story.

When I asked if she had taken the suggestion, I got a story for an answer. “Ernie was on a show called Butternut Square. And I asked my pupils to write him a letter about what they liked best, and they wrote they loved the part where he dressed up. So I sent Ernie all their letters telling him that. And then his own show airs and it’s called Mr. Dressup.” The program went on to become one of Canada’s most beloved children’s shows. Maybe Mum had something to do with that.

“How good to receive your news!” Rogers wrote when she won Mrs. Chatelaine. “We’re delighted for you. As you go into the tv studios just remember how much joy you’re bringing to the people who will be watching AND LISTENING. You will be telling how a growing family has always worked at living together creatively. . . . Since Marshall McLuhan (another creative Canadian) calls tv a cool medium (one which can command a lot of participation) you have the chance to illicit [sic] a lot of positive response.”

The day after we first read Rogers’s letters, I took Mum to see A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, the 2019 film about Rogers. There’s a moment when Tom Hanks asks us to think about the people who helped us become who we are. I looked at Mum. She was crying. She always gets teary when she tells a story about someone believing in someone else. The Group of Seven painter Lawren Harris’s belief in Emily Carr, before she became a famous artist herself, is Mum’s favourite in this genre. Later, I asked her if Rogers was the Harris to her Carr. “I never thought of it like that before, but yes, I believe he was.” Mister Rogers’s love and land of make-believe live on.