After my boyfriend, Gabriele, and I arrive at the two-track village of Ortona, we walk to La Fontana Dell’Amicizia, “the Fountain of Friendship,” in the Piazza degli Eroi Canadesi—“the Place of the Canadian Heroes.” Shaped like a maple leaf, the fountain spurts water lit in the colours of both the Canadian and Italian flags, which also billow behind us. A large black granite marker next to the fountain reads, “Canada and Italy: war brought us together, and peace made us friends.”

I burst into tears. Gabriele pulls me into a hug. Across the way are cafes patronized by aging nonni who sit in the sun with their drinks.

You could say this is a homecoming for Gabriele, as his family comes from Pescara, the next town. In many ways, it is a homecoming for me too, even though I’ve never been here and I’m not Italian.

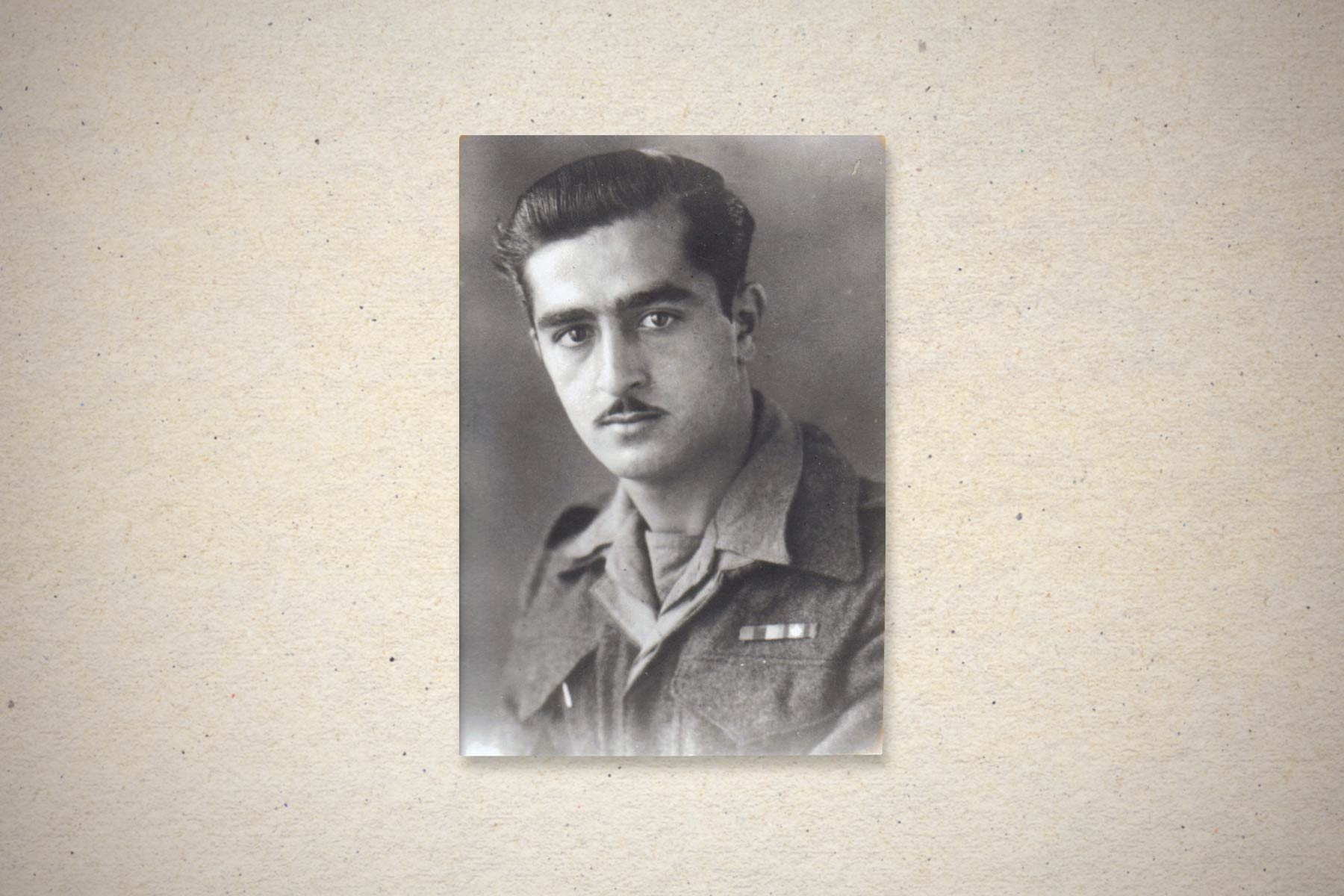

We are here because my jido—my grandfather—was an infantryman during the Second World War. He was among the Canadian troops sent to Ortona in December 1943 to take back the town from the occupying Nazis. I have read everything I can about the Battle of Ortona. I know that, after six days of fighting, the German paratroopers retreated under the cover of night. The Canadians considered themselves victorious, though they suffered hundreds of casualties and most of Ortona had been destroyed.

While Jido was one of the lucky few who managed to make it home after the war, he was not without scars. The Battle of Ortona left him deaf in one ear; shrapnel was permanently embedded in his back. He also had post-traumatic stress disorder. I’m told that, for decades after the war, whenever a car backfired or the sky produced a thunderclap, he would dive under the table. He died in 1982, at the age of fifty-nine, from leukemia and a heart attack. I was a baby then and have no memory of him, but there are pictures of us together. In some of them, he’s holding or tickling me.

For most of my life, stories abounded of Jido as a man with a devilish sense of humour, as a doting husband, and as a loving father. But he never spoke about his war service, and even my sito, my grandmother, couldn’t tell me anything about that period of his life. Though I always wondered about the enigmatic veteran in my family, the Second World War seemed abstract, something that had happened a million years ago on the other side of the planet.

When my sito passed away, in 2016, I inherited all of Jido’s things that she had meticulously preserved: his war medals, his dog tags—barely legible—and his service records. Running my fingers over original telegrams and marconigrams sent to my great-grandmother, informing her Jido was missing in action on two different occasions, suddenly made the war more immediate, more tangible. It was something I could hold and feel between my fingers.

Still, I never got the chance to ask Jido all the questions brewing in my head: What did he see? How many people did he kill? How many friends did he lose? What did the battle rip from him? It took the racist comments of a national icon to propel me to dive deeper into those questions.

In 2019, Don Cherry, former co-host of Coach’s Corner, infamously derided new Canadian immigrants for neglecting to wear the poppy during Remembrance Day. Denigrating new Canadians as using the country for its “milk and honey,” Cherry used the term “you people,” a racist dog whistle, during a national broadcast.

I tweeted at Cherry, telling him about Jido, who was one of the few Arabs in the Canadian army at the time. My family is Syrian and Lebanese, having emigrated to Montreal over 120 years ago, and I wanted to prove that non-white immigrants had also fought to defend this country. My post garnered enough traction on social media that it caught the attention of news outlets. I was invited to speak about Jido on CTV News Network and CJAD 800. But even as I was interviewed on television and radio programs about how proud I was of having a war hero in my family, I didn’t know what that truly entailed.

Cherry was eventually fired for his comments. But given the widespread racism in the Canadian Armed Forces, coupled with the ongoing anti-Arab and anti-immigrant rhetoric in our culture, I felt I had to honour Jido—to walk in his footsteps and bear witness to what the war took from him.

When you’re missing integral pieces of the puzzle, there’s little choice but to do the work yourself to fill in the blanks. Being in Ortona, surrounded by green olive orchards and the remnants of bombed-out cathedrals, I could feel the pieces of Jido he had left behind.

Jido’s father, Michael Zarbatany, fled Damascus in 1906 with his Lebanese wife, Mary Attabe, and was the priest at one of the oldest Syrian Orthodox parishes in Canada, St. Nicholas Antiochian Orthodox Church, which still stands to this day, in Montreal. Michael was also a justice of the peace and started the first Arabic-language newspaper in Canada, called Ash-Shehab, “the Brilliant Star.”

As I went through Sito’s records, I found myself tickled by the idea that Jido, by contrast, was a bit of a rebel. His report cards from 1939 show him antagonizing his teachers by smoking tobacco while at school and eternally arriving late for class. “This is ridiculous!” one report card screams. That year, when the Nazis invaded Poland and war was declared, Jido lied about his age—he was only sixteen—and volunteered to join the Canadian Armed Forces. He was placed with the Loyal Edmonton Regiment and shipped off to London, then North Africa, before he fought his way through Italy. By the time he engaged the Nazis in Ortona, Jido was twenty years old. Many in his band of brothers were barely eighteen. His letters home had no mention of what he was seeing in Italy, just pleas to his mother not to worry about him.

I’ve read about intergenerational trauma, the idea that our ancestors’ pain can be passed down. Looking around Ortona, bullet holes still peppering the bricks, I can feel something in my bones, haunting me. As Gabriele and I move through the village, visiting the Santa Maria di Constantinopoli cathedral where the Canadians held Christmas dinner during the battle in 1943, I have the strange sense that I’ve already been here—as if memories are being transmitted to me. I imagine men clinking their standard-issue tin cups, filled with beer and local wine. The scrape of cutlery against dishes. The smell of pork with applesauce, boiled cauliflower, mashed potatoes with gravy, and mince pies for dessert. I imagine the snap of a Christmas cracker, the paper crown placed atop a soldier’s head, and the low humming of “Silent Night.”

Right as we pass the Price of Peace statue, which depicts a Canadian soldier hovering over a wounded comrade, we hear music from a solo trumpet—a somber and solemn tune, not unlike “The Last Post”—playing through an open window overlooking the steep ridge that drops down to the water.

At the visitor’s centre, the staff tell us that some of the men from Jido’s Loyal Edmonton Regiment lie buried in the Moro River Canadian War Cemetery, a few kilometres south of the village. We bike part of the way and then continue on foot, hiking up a winding back road and then cutting through a private olive orchard—the harvest in progress—to reach the cemetery. As we walk, I wonder if this was the site of one of the Germans’ famous ambushes. In his book Ortona: Canada’s Epic World War II Battle, military historian Mark Zuehlke describes how, at one point, the Germans emerged from their positions with hands raised in surrender. As Canadian soldiers walked out to meet them, he writes, “the Germans dropped to the ground, as if on command, and a machine gun emplaced behind them ripped into the Canadians.” Jido, did that happen here? I wonder. Did it happen to you?

There are 1,375 Canadian soldiers buried in the cemetery, and over fifty of the graves are of soldiers who were never identified. As we pass gravestone after gravestone, it strikes me that I’m able to visit their final resting place only because Jido isn’t buried here. Had he died in the battle, I wouldn’t exist.

It’s at this moment that I recall the story Sito loved to tell about meeting Jido after he had settled back into civilian life. It was 1947. She was sitting in a booth at a soda shop on Bélanger Street in Montreal with her girlfriends when in he walked. Upon their introduction, he pointed squarely at her and said, “You I’m going to sleep with.” She smacked him right across his face.

Holding his cheek, he barked, “What are you doing, you dumb broad? I’m paying you a compliment!”

“Those kinds of compliments I don’t need,” she retorted.

A year later, they were married.

I want to laugh at the brazen meet-cute, but the cemetery is quiet. We see no other visitors there. I wonder if those buried here have any visitors at all.

In this moment, I realize that, in my case, a large part of my remembrance involves this pilgrimage to a small village hovering on the Adriatic to confront Jido’s trauma, passed down through the blood, taking decades to be fully grasped. I can picture before me a twenty-year-old kid advancing through this town as his brothers in uniform vaporize next to him in a cloud of pink mist, an experience that forever changed his relationship with the world around him.

But another part—equal in size and loaded with just as much meaning—is remembering all aspects of Jido beyond his wartime service. Jido was his own person before the war—sometimes impish, often hard-headed, fiercely loyal to those he loved—and the war didn’t change that.

He travelled the world with Sito. When they had my mother, he raised her under his watchful eye, curiously enough allowing her to become a belly dancer but drawing the line at letting her see the Beatles live in concert. He lived to see his only daughter marry in the ’70s and to meet his two grandchildren in the ’80s—albeit only briefly before the war raging in his own veins caught up with him.

I can admire the man beyond the “war hero” moniker. When I was little, Remembrance Day ceremonies and commemorations were a chore—long school assemblies, reciting “In Flanders Fields” by heart, making poppies out of red cardstock. Now, Remembrance Day, for me, isn’t just about commemorating brave acts on the battlefield. It can also be about smiling about a life well lived, even when it isn’t pretty or something you would pin to your lapel.

On our last night in Ortona, Gabriele and I return to the Canada–Italy friendship fountain, which is arcing red and white lights through the streams of water. Grabbing a piece of chalk, I stand in the middle of the maple leaf and write:

“Victor Zarbatany was here, 1943.”