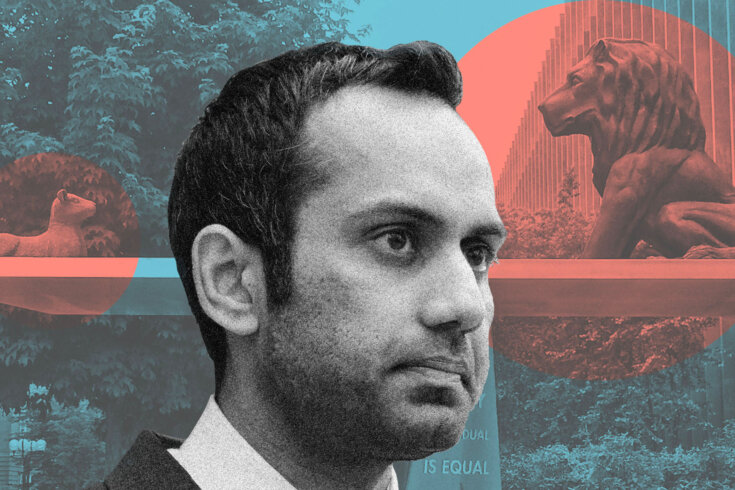

On April 21, a jury found Umar Zameer not guilty of murder in the death of a Toronto police officer. The horrific accident that occurred on July 2, 2021, and the policing and prosecutorial breakdown that continued until Zameer’s acquittal nearly three years later, should never have happened.

Given the maelstrom surrounding the conclusion to this highly emotional trial, Toronto Police Service chief Myron Demkiw has initiated a “full internal review” of the many things that appear to have gone awry in the case. While the history of cops investigating cops has not been inspirational, it’s an opportune time to lay out the major questions that must be addressed.

First, policing practices. Close to midnight on Canada Day, TPS detective-constable Jeffrey Northrup and his partner, then detective-constable Lisa Forbes, were responding to reports of a stabbing in the vicinity. They were in plain clothes. Police officers assigned to work out of uniform do not generally respond to emergency calls. Their main purpose is to blend in for surveillance and undercover purposes.

The officers had a description of the suspect: Brown, heavy set, with a long beard and big hair. Of these identifiers, Zameer presented only one: he was Brown. Nevertheless, the plain-clothes officers approached Zameer’s vehicle in an underground parking garage, indicating he turn off the engine and exit. His pregnant wife and toddler were inside with him.

Panicked that he was being ambushed by criminals who he says were shouting and banging on his vehicle, Zameer attempted to drive away. With his front path blocked by an unmarked police van with tinted windows, Zameer reversed and conducted a series of manoeuvres to escape. In the process, Northrup was struck, run over, and killed.

The police should never have impeded Zameer from driving away that evening. Over the course of the trial, Forbes admitted that there had been no legal basis for an arrest or detention: Zameer did not closely match the description of the suspect and, without any such reasonable suspicion or cause, was not compelled to stay on the scene to answer any police questions. Beyond arguments regarding civil liberties, there is a high risk that a citizen would fail to recognize an advancing, shouting figure in ordinary clothes as a police officer. In the circumstances, it would have been far safer to rely on underground video surveillance records and note Zameer’s licence plate and then follow up for any potential investigation.

The remedy requires a focus on two separate issues. First, the continuing failure of TPS questioning tactics. The botched Zameer detention comes on the heels of decades of street-check—or “carding”—controversies, where the TPS (and other police services) have been criticized for stopping and questioning citizens, particularly people of colour, who are not suspected of specific crimes. Legal experts have been clear such practices violate Charter protections against arbitrary and unlawful use of police power. It would seem from Zameer’s case that repeated civilian oversight and court direction have had little impact on TPS conduct.

Second is the question whether it is safe for officers without highly identifiable uniforms and protective police gear to respond to urgent calls. Over the course of the trial, Zameer was clear he mistook the police officers as assailants. In a society where hate crimes are on the rise—with the vehicular murder of a Muslim family by a self-proclaimed white supremacist in London, Ontario, just weeks before the Zameer tragedy—the risk of panicked misidentification of plain-clothes police is high.

From there, the Ontario Provincial Police, which will conduct the review, must proceed down darker paths, involving the allegedly inaccurate testimony given by officers on the scene of Northrup’s death. Forbes, along with two others in plain clothes who arrived during the incident, testified that Northrup was standing in the pathway of Zameer’s vehicle with his hands outstretched when he was run over. This testimony was not only contradicted by security camera footage, but experts in accident reconstruction—called by both the defence and the Crown—also concluded that Northrup fell after being side-swiped by the reversing vehicle and was then run over, likely unseen, when the vehicle advanced.

Justice Anne M. Molloy instructed the jurors to consider the possibility of collusion between the officers, noting the implausibility of all three officers being wrong in exactly the same way. Collusion can take many forms—from professional error all the way to criminal act. Without jumping to conclusions, any review of the Zameer case must follow the facts to determine if the police made procedural mistakes or outright lied.

The trial also established that a group of officers—including two who were on the scene, then another who arrived as Zameer was being arrested—wrote their notes about the incident at the same time, in the same room, roughly one month after Northrup’s death. Police guidelines dictate that police write up their notes independently, since inconsistencies in human memory are expected and need to be interrogated through a review of multiple sets of notes. Police officers are certainly not meant to engage in what Molloy disparagingly referred to at trial as a “note making party,” according to the Canadian Press. Left unanswered at trial was the question whether any collusion happened. Were there conversations about Zameer amongst the officers involved? Is there any evidence to suggest a willful misrepresentation of facts—which would take us into the realm of perjury?

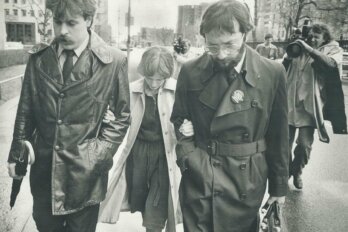

These are harsh questions. But they are necessary, based on the extensive reporting, notably by the Toronto Star and the CBC, of the prevalence of police officers lying in criminal proceedings. Most of this lying has had to do with police patching up procedural violations in their investigations, such as justifying illegal vehicle stops and searches. However, police perjury—“testilying,” as it is euphemistically known—has been committed to cover up excessive use of police force in both Canada and the United States. The 2008 case involving Jason Arkinstall stands out. Arkinstall was arrested by officers in Calgary and charged with obstructing, threatening, and assaulting a police officer. In court, bystander video showed that police had smacked an already handcuffed Arkinstall on the back of his head and thrown him head first with such force into a police van’s rear cage that his flailing legs almost hit the van roof. Prior to the video being revealed as evidence, one of the officers denied their actions and claimed that it “didn’t happen,” according to the Toronto Star.

The spectre of testilying implicates the Crown too. Crown prosecutors do not exist for the purposes of “nailing” the accused. Rather, they are there to serve as agents of justice. It is the responsibility of the Crown to push the police on any inconsistent evidence and to seek out any exculpatory evidence. And it is their responsibility to adjust their prosecution to new evidence as it emerges.

There are doubts whether the Crown met the standards of justice in Zameer’s case. It is now public knowledge that the judge at bail court in the fall of 2021, Justice Jill Copeland, was extremely unimpressed by what she described as the Crown’s “weak” murder case attached to an implausible motive. On multiple occasions at formal trial, Justice Molloy was frank—first with counsel and ultimately with the jury—that there was little to no evidence in support of first- or second-degree murder convictions.

As such, an investigation must probe whether the Crown’s office was pressured to proceed with a murder trial based on evidence that began as shaky and utterly fell apart with time.

That pressure may have been political. Statements made by Ontario premier Doug Ford, then Toronto mayor John Tory, and Brampton mayor Patrick Brown condemning Copeland’s decision to grant Zameer bail in 2021 all carried a heavy implication of presumed guilt. Tory and Brown have since issued more sober second thoughts, with Ford offering that he was working with “limited information” at the time. But Chief Demkiw’s vocal disappointment in the outcome of a trial also raises fears of police pressure on the Crown’s office. While Demkiw, too, has helpfully walked back his comments, it’s a reminder Crown prosecutors have well-established relationships with police—not only professional interdependencies but often friendships that extend beyond the office. It is for this reason that police deaths caused by civilians should in future be referred to independent prosecutors from outside the jurisdiction in question—mirroring the current policy for when police cause civilian deaths.

Systemic issues and human shortcomings have led to a tragic death and the three-year derailment of the life of an innocent person and his family. “You have my . . . deepest apologies for what you have been through,” Justice Molloy told Zameer following his exoneration. Beyond apologies, Zameer, police officers, their families, and Canadians deserve a thorough investigation and substantive reform of policing and prosecutorial policies to prevent a repeat of such tragedies.