Ezra Levant rolls up in his silver 2003 Acura MDX at a deserted gas station in Calgary’s south end, ten minutes late for our meeting. After months of trying, the only time he has available to connect is Sunday night at 10:30, for the first leg of a twice-weekly commute to Toronto to film his Sun TV current affairs show, The Source. He greets me warmly, opening the passenger window to lean over and shake my hand. His casual khaki shorts, yellow golf shirt, and tousled salt and pepper hair are oddly offset by brown dress shoes and socks. “Jeff Nield, what’s it been? Thirty years? ”

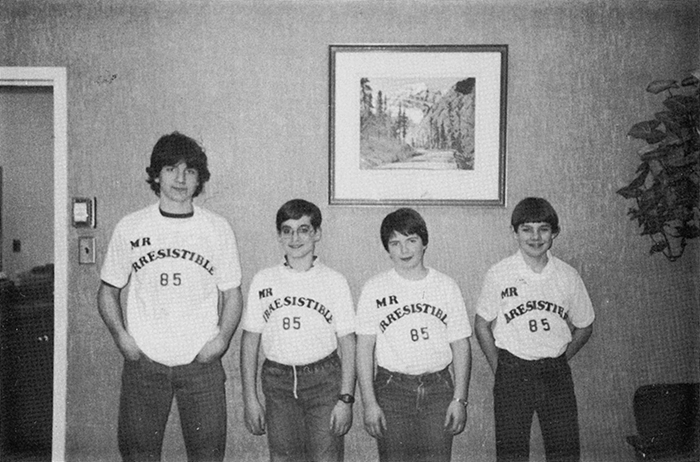

Long before he became Canada’s answer to Glenn Beck, he was a self-proclaimed mouthy kid growing up in a tony rural suburb of Calgary. I met him in 1982 at Springbank Junior High, where he says he learned that his gift of gab could help him get ahead. I ask him if he remembers the time in grade eight when he competed for the title of Mr. Irresistible. “I guess that was my first campaign,” he says. The goal was to get girls to hand over the paper hearts they were allotted for the contest. It probably wasn’t Ezra’s oversized wire-rimmed glasses or his T-shirt tucked in to the elastic waist-band of his jeans that won the ladies’ hearts; he really wanted to win, so he used what he had to make that happen: “I politicked.”

Seeing Red

Savvy Democrats don’t talk about tax relief

Kelsey Heinrichs

By the time President George W. Bush delivered his acceptance speech at the 2004 Republican National Convention in New York, the catchphrase “tax relief” had entered the vernacular. He spoke of the “energy and innovative spirit of America’s workers,” and of having “unleashed that energy with the largest tax relief in a generation.” Such rhetoric taps in to our unconscious and the frames embedded within, according to George Lakoff, a linguistics professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and a respected—if polarizing—figure in both the ivory tower and party politics. “For there to be relief,” he explains in his 2004 book, Don’t Think of an Elephant!, “there must be an affliction, an afflicted party, and a reliever who removes the affliction and is therefore a hero.” Democrats who speak of tax relief implicitly agree to the debate on their opponents’ terms, he adds, losing ground before the argument has even begun.

—Julien Russell Brunet

Casually cruising down the six-lane Deerfoot Trail en route to the airport, he is still politicking. While more subdued in person than on the air, he takes control of the conversation to rail against “radical” imams, race-based quotas, and “Astroturf” environmental organizations. He calls himself a libertarian, “basically someone who believes in freedom,” though he admits to more mainstream conservative leanings when it comes to social issues and foreign affairs: “It’s tough to be a pure libertarian, because reality has a way of messing with that beautiful theory.”

He claims to have acquired his love of freedom in Springbank, living “among cowboys and Indians.” While there was certainly a sprinkling of students from ranches and reserves, my recollection is that most of us were the sons and daughters of doctors, academics, executives, lawyers, and the like. He tells me that both his sets of great-grandparents were European immigrants–cum–homesteaders. From those humble beginnings, his mother, Leslie, earned four university degrees; and his father, Marvin, became a radiologist. “And here I am a troublemaker,” he deadpans.

He clearly relishes the role, beginning every episode of The Source with a rant, applying a heavy dose of moral certitude to his chosen topic of the day. He is also a frequent contributor to the Sun chain of newspapers, makes appearances at high-profile right-wing events, and has graced bestseller lists. He has written six books so far, from Fight Kyoto and Ethical Oil to this year’s The Enemy Within: Terror, Lies and the Whitewashing of Omar Khadr, in which he likens his subject to Paul Bernardo. Such hyperbole tends to attract attention, and not always of the positive variety. “You know, I’m gonna keep my family life private,” he says, when asked what school his two young children attend. “Just for security reasons.”

He doesn’t keep in touch with many people from his Springbank days, “beyond Facebook updates.” After he graduated from junior high in 1986, his intellectually ambitious family enrolled him at Western Canada High School, a prestigious institution inside Calgary’s city limits. There, he took up formal debating, and continued with it at the University of Calgary. He would win gold at the Inter-Collegiate Business Competition four years in a row, the first two while teamed up with Calgary’s current (and left-leaning) mayor, Naheed Nenshi.

“Their debates were less about content and more about style,” says Robert Schulz, a professor with the university’s Haskayne School of Business. As Levant’s debate coach and mentor, Schulz remembers a hard-working student with little ego, a polite young man whose skills were honed in the family home. “The best debaters are born around the dinner table,” says Schulz. He is, of course, proud of Levant’s success, but also betrays some regret about what his star pupil has become: “I don’t know whether that’s Ezra, or if that’s what other people who are paid expect him to do.”

Levant parks his Acura in the airport lot, grabs his overnight bag, and invites me to walk him through the electronic check-in to security. He talks the entire time, not letting silence gain any sort of foothold. Perhaps he’s using an old debate tactic designed to buy time until he finds the precise phrase he needs to get his point across. Schulz calls this “squeezing the words,” a trademark of many great speakers, he says, including Martin Luther King. At a Tim Hortons strategically located outside the gate, he thanks me for my time and shuffles off. His wall of noise has been satisfying, in a way. My old schoolmate has found the perfect niche. “Mouthy guys tend to like freedom of speech,” he had quipped earlier, “because they believe in settling things through verbal quarrels, not fisticuffs.”

This appeared in the November 2012 issue.