I’ve never met Garnet Rogers. For all I know, he’s a very nice man; like his late brother, Stan, he sure can sing. But ten years ago, he nearly killed me at Ottawa’s tulip festival, and I’ve wondered ever since whether certain musicians shouldn’t issue statements at the beginning of their concerts: Warning: This performance contains vocals, lyrics, keys, and chords that may induce debilitating sorrow in some listeners. Listener discretion is advised.

I don’t remember the actual song, only the abject melancholy that flooded through me upon hearing Rogers’ spare guitar and soulful baritone waft over the crowd of happy, paint-faced children, batik peddlers, and poutine eaters wandering amid the waving tulips. No one else seemed particularly bothered by the dissonance between song and scene, but all I wanted to do was escape down to the riverbank and weep.

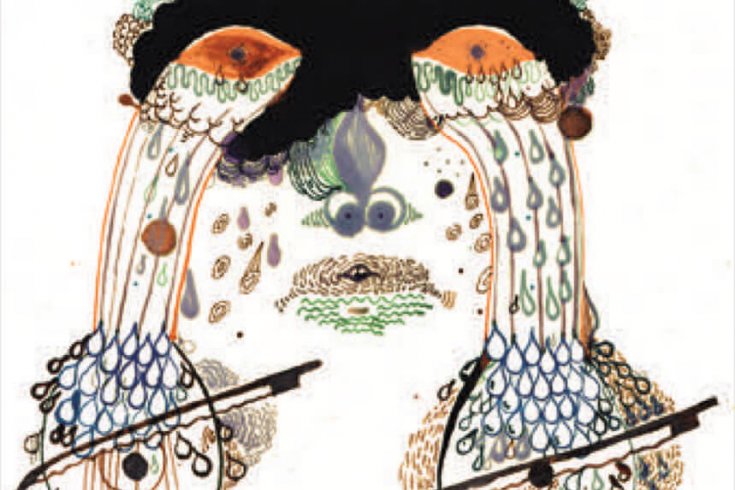

It wasn’t the first, nor last, time a piece of randomly encountered music would ambush me, and amplify my sadness, almost unbearably. Once, it was the mournful saw of violins accompanying a video at the Canadian Museum of Civilization about early logging. Or it could be a Rufus Wainwright song sneaking up on me from the car radio. I soon became hypervigilant at recognizing that first down spiral of mood, and adept at the quick lunge for the off button. Music, once a comfort and a source of pleasure, had become a minefield.

Sensitivity to sad music was just one troublesome symptom of what was eventually diagnosed as clinical depression. It was only after many months of taking citalopram—a common drug in the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (ssri) category—that I realized the sad-music thing wasn’t happening to me anymore. Puttering in the kitchen one morning with the radio on, the sound of a violin stopped me—“Field of Stars,” by violinist Oliver Schroer, a song recorded during his walk along Spain’s ancient pilgrim trail, the Camino de Santiago. Schroer’s wailing fiddle, echoing through an old stone chapel, did make me sit down and let the tears come to my eyes—but they were the cathartic, opening kind.

Soon I stopped fearing music, maudlin TV commercials, and Animal Planet programs about cruelty to chimpanzees. I was still able to feel sadness, but I was not so overwhelmed by the emotion. And I became curious; exactly what was going on in my brain to make me so vulnerable to music in the first place—and why was a pill able to change all that?

Antidepressants, we know, affect the activity of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, and hormones such as oxytocin, all of which are involved in the experience of pleasure. These are the hormones that become seriously impaired when a person is depressed. But what is the specific link—if it exists—between mood and musical expression? Searching for answers, I turned first to the neuroscience of music, a thriving field of research that has spawned two current bestsellers—Oliver Sacks’ Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain, a collection of strange tales about the human relationship to music, and Daniel Levitin’s This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession, which details recent neurological findings. Among them: what’s happening in the brain when music uplifts us; why bits of music can lodge in the brain (the dreaded “earworm” or “tune cootie”); and theories of how and why music—in all its pitches, tempos, keys, and rhythms—has played an integral role in the evolution of the human species.

Levitin is a psychology professor who runs the Laboratory for Music Perception, Cognition, and Expertise at McGill University. Before becoming a psychologist, he was a session musician, sound engineer, and record producer for the likes of Stevie Wonder and Blue Öyster Cult. When I call him on the phone, he sits down at the piano in his Montreal home and plays a riff of trilling high notes, followed by a slow series of notes lower down the scale. It makes the obvious point, that what we think of as sad music tends to be quieter, lower, and slower, with longer duration in tones and a darker timbre than “happy” music. But why one person listening to such music would recognize, but not necessarily feel, the emotion of sadness, while another is consumed by it remains a difficult question to answer. “The relationship between art, creativity, and mental illness is not easily reduced to brain parts,” Levitin admits. “There’s a messiness to emotions, [and] I’m not sure I’m willing to say that it’s a disorder—that someone who is deeply moved by music needs to take a pill.”

He goes on to quote a conversation he recently had with Joni Mitchell. “I said I’d had a difficult period with some colleagues and had found it hard to control my emotions, to which she said, ‘Why the hell would you want to do that? ’ For an artist like Joni, the whole point is to be completely in touch with the volatility of emotions.” Stevie Wonder once told him that “he often couldn’t finish a take, because he’d be on the verge of tears. I don’t think that’s a bad thing.” Artists offer consolation, Levitin says. “It’s like you’ve been cut off from your emotions, and suddenly there’s another person feeling what you want to feel. They’re on the cliff edge with you, and, more than that, they’ve taken their despair and turned it into a beautiful piece of art. It’s inspiring.”

In Musicophilia, neurologist Sacks praises music’s ability to restore pleasure and feeling to those numbed by grief, and recounts how, after the death of a beloved aunt, he couldn’t mourn, until he attended a concert and heard The Lamentations of Jeremiah, by an obscure contemporary of Bach named Jan Dismas Zelenka. “My emotions, frozen for weeks, were flowing once again.” After the death of his mother, he walked around New York, “lifeless as a zombie,” until he heard strains of Schubert from an open basement window. “I wanted to linger…Schubert, and only Schubert, I felt, was life.”

If Sacks were to visit the International Laboratory for Brain, Music, and Sound Research in Montreal, he would make an ideal subject for research undertaken by neuropsychologist Robert Zatorre and his McGill associate Anne Blood. In 2000, they performed positron emission tomography (pet) scans on ten McGill students trained in music as they listened to pieces they had chosen, and to which they had previously had “an intensely pleasurable emotional response,” including the all-important “chills.” Selections included the Intermezzo from Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in D Minor, and Barber’s Adagio for Strings. Blood and Zatorre found that the greater the chills, the more they observed changes in heart rate and respiration, and the more blood flowed into brain regions believed to be involved in reward and motivation, emotion and arousal—the same pleasure centres stimulated by food, sex, and addictive drugs. “Music, although it is abstract, still seems to activate the same neural pathways,” says Zatorre.

The question, of course, is why. For Zatorre and many other neuroscientists, what goes on in the brain’s substrates is linked to the very essence of human evolution. “An animal needs something to tell it how to survive, and the way the brain reacts to music seems to be akin to the way it reacts to all the things that are important to survival.”

That argument is taken further by Canadian-born musicologist David Huron, now head of the Cognitive and Systematic Musicology Laboratory at Ohio State University, and author of Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. Interviewed over the phone, with a purring cat on his lap (“I’m getting a nice rush of oxytocin here”), Huron is exuberant as he describes his research, which included an experiment he conducted as a professor at the University of Waterloo. He was studying the effect sad or happy music might have on the perception of a group of Psychology 101 students, who had been told that the experiment had a different goal entirely: to study changes in their heart rates. Half the students listened to “happy” music—a selection of bluegrass tunes. (Huron calls it the Steve Martin effect: “It’s hard to play sad music on a banjo,” he says, for musicological reasons that have been dissected at great length, but which seem to boil down to the fact that banjos “plink,” while more resonant instruments such as the guitar go “dnng.”) For the sad-music group, researchers selected tracks from Brian Eno’s Apollo: Atmospheres & Soundtracks. Each group listened to the music for fifteen minutes. Then a researcher interviewed the students, asking them, among other things, to estimate how well they would do in their final grades.

Huron and his colleagues were gratified to find significant differences between the groups’ assessments of their likely academic performance. Those who had listened to the happy banjo music tended to overestimate their marks, while the Eno listeners were much more realistic. “It’s almost as though when people listen to sad music, it’s a way of grounding themselves,” Huron concludes.

Whatever effect music may have on us, it is a form of “drugs without the drugs,” says Huron, happily. In fact, in subsequent research into the sad/happy music question (one of his studies will soon appear in the Empirical Musicology Review), he has suggested clear links between our responses to instrumental music and human speech. He described a distinct progression in the emotional experiences of subjects who reported their feelings upon listening to sad music: first, an empathy akin to what they might feel hearing the voice of a loved one in pain; then a flood of associations in the “acoustic cues,” triggering memories involving the music (the proverbial “they’re playing our song” phenomenon); finally, rumination or “sad thoughts.”

Huron also sees an evolutionary link in his findings. When we respond to music with chills down the spine, for instance, we may be experiencing something akin to what a mother would feel hearing the cry of a lost child: we become hyperalert and focused, with adrenalin at the ready—whatever it takes to find and protect the child.

When music makes us cry, Huron points out, our tears are filled with the hormone prolactin, which is integral to the essential human bonding experience of breast feeding, and which women produce in greater quantities than men. This, along with the release of hormones such as dopamine and oxytocin, mimics the well-being we feel in the most intense moments of connection with others—nursing an infant, having sex, receiving praise. “It’s biology wrapping its arms around you and saying, ‘there there,’” he says. In an abstract for an article entitled “Why Do Listeners Enjoy Music That Makes Them Weep? ” Huron writes: “I suggest that the pleasure of musically induced weeping arises from cortical inhibition of the amygdala, and is linked to the release of the hormone prolactin…Weeping shares a deep kinship with laughter, frisson (‘chills’), and awe (‘gasping’)—responses that philosopher Edmund Burke called the ‘sublime emotions.’”

Of course, this paradoxical dynamic—seeking out a “sad” song in order to feel “happy” in the end—doesn’t work for the depressive. The tears may flow, the heart rate might change, but there’s no “there, there” there.

For research into the brains of the mood disordered, I had to turn from musicologists to the work of Richard Davidson, a professor of psychology and psychiatry who runs the Laboratory for Affective Neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Davidson is known for his research into the brain’s plasticity—its ability to change and to heal. He and his colleagues have found that the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus (all parts of the brain that respond to music) in depressed people show clear differences from those in normal subjects. And one result might be, in one of my favourite phrases ever, “context-inappropriate emotional responding”—tears at a tulip festival, for example. But his research also represents good news: brains can change, for the better, through many therapies, including antidepressants.

Most of us, depressed or not, have had the experience of being profoundly moved by a piece of music when we hear a particular sequence of notes, played in a particular way, at a particular time in our lives. In the normally functioning brain (as opposed to the depressed brain), sad music may actually perform the function of restoring our happiness—or at least our emotional equilibrium. Sad music, as Huron suggests, may ground us. This may explain why anyone can go online and find lengthy discussions among people who, far from avoiding Garnet Rogers and Rufus Wainwright, actively seek, share, and revel in sad music.

“Can anyone recommend some pensive, melancholy, dirge-like chamber music for rainy days and blue moods? ” writes “Crotalus” on the website Ask Metafilter. “Thanks.” Among the many, wildly eclectic suggestions he received: Albinoni’s Adagio, Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten by Arvo Pärt, the album Early Music by Kronos Quartet, instrumentals on David Bowie’s album Low, and the soundtrack from the film Donnie Darko.

As for me, I’m not going out of my way to see Guy Maddin’s film The Saddest Music in the World, but Garnet Rogers, Rufus Wainwright, and a host of other favourites are once again welcome on my iPod. I’m grateful to have that restored as a listener—the strange human capacity to enjoy feeling sad.