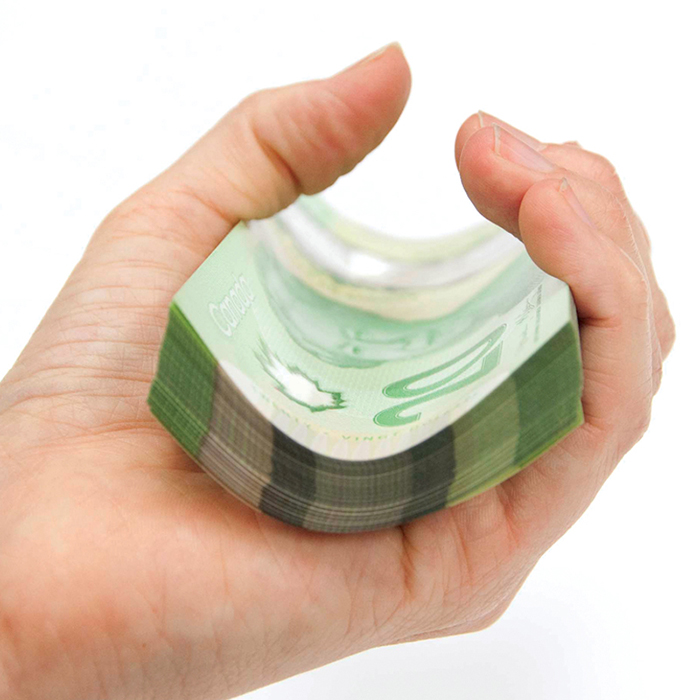

Courtesy of Bank of CanadaThe Bank of Canada’s new polymer $20 note.

Courtesy of Bank of CanadaThe Bank of Canada’s new polymer $20 note.Feel. Look. Flip. These are the Bank of Canada’s instructions for verifying its polymer banknotes. This month, a new $20 bill goes into circulation, the third instalment in the series launched last November. Take one in your hand. It feels different, the polymer smooth and creamy, the edges sharp. It’s green, as before, but now a transparent window transects the right side of the front. Queen Elizabeth II resides in her usual place, but her portrait has aged to reflect her years; she also gives her best Mona Lisa smile from the centre of the transparency. Flip the bill over. Gone are sculptor Bill Reid’s mythic Haida messengers, replaced by soaring stone towers and the equally mythic, if more Eurocentric, half-clad figures of Peace and Justice—part of a new sketch of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, which was unveiled in France during the summer of 1936.

Banknote design is a long, collaborative process. This redesign was announced in 2006, and followed by extensive consultation with law enforcement agencies, financial institutions, business owners, and the public. The resulting imagery draws on ideas presented by focus groups of “ordinary Canadians,” a tactic meant to defuse the minefield of how to represent our national identity. After the motifs were chosen and the designs settled, the bills went back to focus groups across the country. But too many opinions can be just as tricky as too few. The hundred was altered after some focus group participants flagged the scientist depicted as too “Asian” looking, perhaps reinforcing a stereotype. Later, the revelation that the Bank of Canada had redrawn the female figure with a more “neutral” ethnicity (read: white) only brought further accusations of racism.

Fake Out

Why counterfeit bills are so rare in the US

Kelsey Heinrichs

To the casual observer, today’s greenback remains deceptively similar to the original 1928 design, printed on a 75/25 percent blend of cotton and linen, but its old school appearance belies the stringent security measures that keep US counterfeiting rates among the lowest in the world: about five bogus bills for every million issued. The Bureau of Engraving and Printing produces 23.5 million notes daily, or the equivalent of $453 million, and monitors fresh sheets from the moment they arrive, wrapped in brown paper, at printing facilities in Washington, DC, and Fort Worth, Texas. The Secret Service also uses two extensive databases to track the location of every seized fake. Even so, in 2005 an estimated $450 billion of the $760 billion in circulation was held abroad and found its way to countries such as Peru and Colombia, where counterfeit American bills are far more prevalent.

—Andrew Nguyen

Focus groups for the $20 bill expressed different misgivings: many were hard pressed to recognize the Vimy memorial, and some even mistook it for the Twin Towers. Others found the half-nude figures “too pornographic.” But the most credible criticism, the one most likely to give us pause, saw the design as a thinly veiled attempt by the Conservative government to recast Canada in a more militaristic light.

Of all the denominations, the twenty is our most iconic, accounting for more than half of the banknotes in circulation. It’s the one you tuck into your niece’s birthday card, hand over to the babysitter, or slap down on the bar to settle your tab. As the most common bill, it is also among the most influential images of Canadian identity.

When the Bank of Canada was established in 1934, a few years after the signing of the Statute of Westminster, it became the sole entity entrusted with issuing Canadian currency. The next year, it printed its first banknotes separately in French and English, using raised ink, fine line patterns, and green dots (the next edition would be bilingual). They featured portraits of royals and former Canadian prime ministers on the front, and allegories of industrial, agricultural, and commercial growth on the back. Canada was not only trying to establish an independent economic footing; it was navigating a new relationship with Mother England. Those bills presented one of the earliest opportunities for cultivating a national identity.

The twenty’s design has maintained several constants over the years, Queen Elizabeth being one of them (with the exception of the 1937 series, which featured King George VI on each denomination). The first twenty was printed in rose ink and carried a portrait of a very young and very cute Princess Elizabeth on the front; an allegory of agriculture graced the reverse. In the 1954 series, that symbolic scene gave way to a more realistically rendered vista of Canada, the rugged Laurentian Mountains. This subtle shift represented Canada as empty, and free from troublesome histories that might include Metis and Native tribes.

The 1960s, leading up to the centennial celebrations in 1967, served as a forge for Canadian identity. The Maple Leaf flag, that quintessential national symbol, was adopted after much debate in 1965 and has been sewn on to backpacks the world over ever since. In 1969, the Scenes of Canada banknote series moved away from the Crown, with the Queen’s visage replaced by portraits of Canadian prime minsters on all bills but one, the twenty; and a new series of scenic vignettes introduced for the reverse. These landscapes were increasingly industrialized and inhabited, reflecting the economic prosperity and independence of the postwar years. Only the twenty retained a romanticized version of the rugged Canadian landscape, in its bucolic view of Moraine Lake in Banff National Park.

By the 1980s, counterfeiting had become a growing concern. The Bank of Canada responded by launching the Birds of Canada series in 1986, incorporating a square metallic patch as an optical security device to combat forgery. This twenty featured the loon, an icon that would become irrevocably associated with our currency when the Royal Canadian Mint launched the loonie in 1987. But rapid advances in colour copier technology made the bills increasingly easier to replicate, and once again the Bank of Canada found itself on the losing side of the war against counterfeiting.

The Canadian Journey series, issued between 2001 and 2006, is the one we are most familiar with today. As well as incorporating multiple anti-forgery technologies, it depicts Canadian cultural achievements, including homages to peacekeepers, hockey, and the arts. The iconography is sophisticated yet accessible, a nuanced expression of Canadian identity that avoids any politically divisive imagery, which is the best-case scenario when it comes to currency design. But the design was short lived. Forgers soon found a way to reproduce the state-of-the-art banknotes, and by 2004 counterfeit bills in circulation reached an all-time high of 470 parts per million (around 20 is considered more acceptable). Another solution was needed.

The polymer series is built around the idea of innovation, and both the iconography and the use of technologically advanced materials are intended to reinforce this theme. The hundred and the fifty, already in circulation, honour medical innovation and “arctic research and protection of northern communities”; the forthcoming ten and five will portray a train (to celebrate what was once the longest railway ever built) and space exploration, respectively. Placed in this company, the Vimy memorial falls woefully out of context. True, the battles at Vimy Ridge were a coming of age for Canada’s identity, but this replica fails to convey the associated pride and sacrifice; it lacks visual resonance.

The shift from peacekeeping imagery, as seen on the Canadian Journey $10 bill, to combat could be read as a signal change in the government’s views of Canada as a global military force, but I’m not convinced. The iconography of the Vimy memorial does nothing to rebrand Canada as a “warrior nation,” and the stoic stone structure commands remembrance and respect rather than glorification.

National symbols are difficult to manufacture. It took some hard-nosed political wrangling to get the Maple Leaf flag passed in Parliament, and even then it wasn’t a given that the design would resonate. As evidenced by the recent kerfuffle over the image on the hundred, design by committee rarely succeeds. The twenty is one of the few pieces of Canadian heritage we handle on a daily basis, one of the last places where cultural identity can be easily built and disseminated. The new version misses an opportunity to inspire. It looks back instead of forward, which is a shame, considering that the polymer banknotes are expected to last more than twice as long as the paper ones.

This appeared in the November 2012 issue.