Each of us walks the world in camouflage. Each of us can be a mystery to ourselves, never mind other people. I’m sure I baffled my father just as he baffled me. He died more than two decades ago, and as the natural, necessary process of forgetting takes hold, any picture I draw of him becomes an exercise in self–portraiture. There are some things I can’t forget. But there’s much I struggle to remember. The work compels me to blend my own features with his.

Harry Abley had a range of identities. He was a son, a husband, a father, a devoted football fan, a migraine sufferer, a proud Canadian and a lifelong Englishman, a close friend of almost no one. At various moments, he worked as a medical–records clerk for Saskatoon City Hospital, a demonstrator of electronic organs at the Eaton’s department store in Sault Ste. Marie, and an assistant to the North American zone controller in the export branch of the Standard Motor Company in Coventry. (That was in the 1950s, when Britain still shipped cars across the Atlantic.) He had no affection for any of these jobs. He did them for the money.

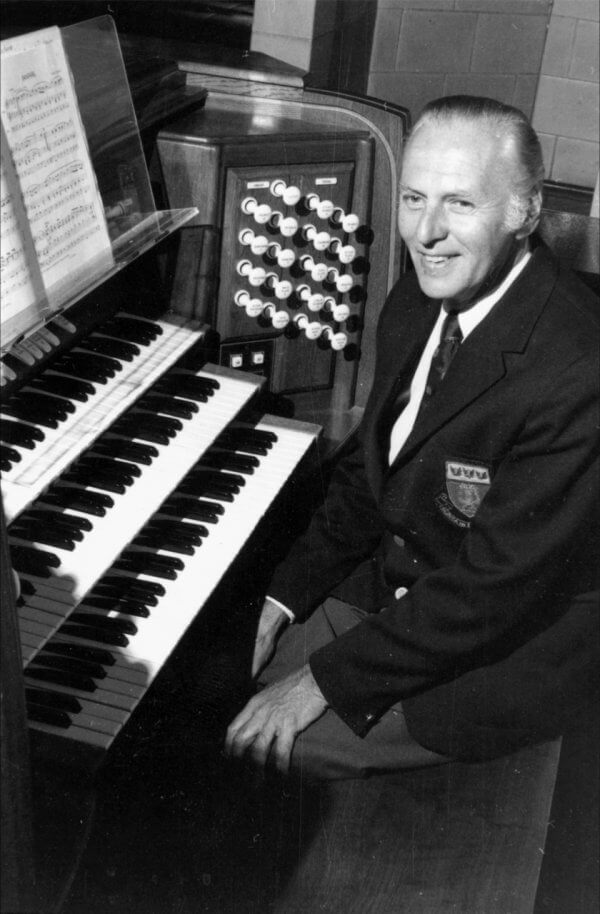

Above all, my father was a musician. He played, he conducted, he taught, he accompanied, he composed. When I was a boy, he would sometimes appear at the dining table with a pencil behind his right ear and an abstracted distracted look in his hazel–green eyes. After a few bites of food and a cursory exchange of words, he would excuse himself, return to the piano—the central item of furniture in each of his many homes—and play, over and over, some musical phrase. Just a few bars at a time, with tiny variations. Listening to him, short sighted as I was, I thought about how my optometrist would keep toying with the refractor’s glassy settings to arrive at a correct prescription. When a melody or chord had been fixed to my father’s satisfaction, and he had scribbled it down on the back of a used envelope or the previous Sunday’s church bulletin, he would resume his meal. My mother could be a stickler for proper manners and polite behaviour. But she tolerated these whims without complaint, knowing they were anything but whims. When my father was composing music—for choir, organ, solo voice, or piano, and occasionally, for other instruments too—he was happy, or something approaching it. Those were the good times, the times when nobody had to worry about his state of mind.

The piano took pride of place in his living room. He would never be at home without one. But the instrument of his life was always a walk, a bus ride, or a drive away: the pipe organ. My father had been learning the piano for four years when, as a boy of twelve, he started organ lessons. He fell in love; he remained in love. A small man with the habits of an introvert and the remnants of a boyhood stammer, he could sit down at the organ bench and fill a cavernous church with as much sound as an entire orchestra. In the Middle Ages, the organ had been nicknamed the “king of instruments,” and my father relished the phrase. He was a prince while performing. The feeling of power this gave him must have been exhilarating. It compensated, no doubt, for much else.

As a teenager, Sunday after Sunday, I heard him play and watched him conduct. Pipe organs are like no other musical instrument: listeners in an audience or congregation rarely see the performer at work. The organist sits at a semienclosed console—a term that refers to the keyboards, pedals, and draw knobs or “stops” on either side of the musician—usually hidden behind a pillar or screen or placed high up in a gallery at the back of a church. There, my father would use both hands to play the keyboards and both feet to play the pedal board. On rare occasions, he might push in a stop with an elbow. The mental discipline required to play a difficult piece for organ is matched only by the physical coordination. The resulting waves of sound emerge from metal or wooden pipes attached to a wall, some distance from the console. To a casual listener in the pews, organ music is born independent of the performer.

When my father was conducting a choir, he might climb down from the organ bench and stand in the central aisle. Now the visible focus of attention, he would make no sound himself; instead, he would use his hands and arms to shape the sounds produced by other people. In style, his conducting was precise and undemonstrative. He disliked conductors who flung their arms around, and he admired Sir Thomas Beecham, the founder of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London, for his ability to direct musicians with a single finger. The robes my father wore in church lent him a certain stature; they emphasized the critical role he believed music should hold in worship.

His profession sent the calendar topsy–turvy. He held choir practices and gave private music lessons on weeknights and Saturdays; the office hours other people kept were a time for him to practise the organ, learn new pieces, and plan the music for services to come. Sunday was the height of his week, its morning worship the climax and justification of the six preceding days. And, to my father, what justified a service was its music. At lunch afterwards, he would seldom mention the sermon—while the priest or minister was holding forth in the pulpit, my father liked to shut his eyes and allow his mind to wander—but he welcomed comments about the prelude, the hymns, the psalm, the anthem, the improvisations, the postlude.

Music showed him a way to God. I suppose it would be an exaggeration to say that for him, music was God; perhaps, though, his God was a heavenly version of Johann Sebastian Bach, a divine artist able to create structures of such transparent beauty and intricate complexity that the cosmos would ring out in harmony. In each of their homes, my mother placed a crucifix on the living–room wall, and my father hung a portrait of Bach on the wall above his desk. Music ruled his life.

It did not rule mine, and therefore, his was a life I could not fully enter. I never took an organ lesson; maybe he was waiting for me to ask, or maybe I was waiting for him. More likely, he needed to maintain a private space away from the demands of his family, just as I needed to create an imaginative world in which my parents would not be dominant. An organ, any organ, no matter how shrill its tone or limited its range, would give him the space he craved. Not every organ held stops that allowed my father to speak with both the voix céleste and the vox humana. Yet he was a master at coaxing beauty out of unlikely vessels, making even the weakest instrument sound sweet or strong. To his wife and child, the language he lived and breathed was a foreign tongue: the language of a distant nation. The language of organists.

The pipe organ has an odd, schizophrenic reputation. It’s easy to have no opinion about the viola or the bassoon; it’s harder to have no opinion about the organ. The noise it makes can be painfully loud—no other musical instrument, without an amplifier, emits so much sound. And, in the realm of popular culture, the organ belongs to Dracula. In a low–budget horror movie from 1960, World of the Vampires, an aristocrat raises the undead by the scary music he conjures from a pipe organ made of human skulls and bones. He flees when he hears a cheerful tune, performed on the piano by the virtuous hero. Sesame Street has a purple–faced Muppet named Count von Count, doubtless a Transylvanian, who plays a pipe organ while counting up to the number of the day. The villain of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast: The Enchanted Christmas is Maestro Forte, a pipe organ with an English accent; he schemes to prevent the Beast from falling in love with Belle. On a more grown–up level, the splendid overture in the movie version of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Phantom of the Opera begins with the sound of a full–voiced pipe organ, whose ferocious arpeggios and pedal melodies smash the quiet and introduce the themes of anger, frustration, and pain that afflict the tormented antihero.

“The organ,” Alex Ross once wrote in The New Yorker, “is an enormous machine on which any idiot can make an impressive noise.” Persuading it to make good music is a trickier proposition. The instrument has, Ross noted, “a diabolical appeal: one touch of a button can unleash mayhem.” Diabolical: a revealing choice of word. Yet despite its affinity with demons, vampires, and monsters, the pipe organ also behaves as the musical voice of Christianity.

It belts out Protestant hymns; it accompanies the Catholic Mass. It provides a soundtrack for baptisms, weddings, funerals, and countless Sunday mornings—a large percentage of the organ repertoire is played before and after services. The link between churches and organs is an ancient one: in 812, a delegation from Byzantium presented a pipe organ to Charlemagne, the holy Roman emperor, and the instrument found a new home in a church in the imperial capital. When a local woman heard this organ’s graceful tones, she died in a fit of joy. Or so the story goes.

To many listeners, even today, organ music is redolent of piety. This sentiment annoyed my father. Even if a composer was personally devout— Bach being the foremost example—my father saw no reason why a prelude or toccata, a fantasia or fugue should be heard as conveying any particular doctrine. Great music needs no external justification, he thought; it speaks to the aspirations of the soul, not the instructions of the pulpit.

“A pipe organ can approximate the voice of God,” Ross observed. “But it also happily evokes a fairground calliope. It is one of humanity’s grander creations, and also one of its more durable technologies.” My father played hundreds of organs over his long career, lending the skill of his limbs and mind to fairground and Creator alike. He performed on Wurlitzers and other theatre organs that were mighty enough to make the cinemas of the 1930s echo with the force of music. He played on small electronic organs not with delight but with a professional determination to make them sound as good as possible. And he gave recitals in churches all the way from British Columbia to East Berlin. Each of these instruments had a different range of sound—specificationis the technical term—depending on the quantity, size, and tone of its pipes, the number of its manuals, and the ways in which the manuals and pedals are linked to combinations of pipes. An organ’s sound is also affected by the acoustics of the building that houses it. The phrase “pull out all the stops” comes from the organ; it’s fortunate for listeners’ eardrums that organists never do this.

To describe the methods by which an organ transmits sound is to demand some fluency in a language bewildering to outsiders. One day, labouring to grasp the process, I looked through Modern Studies in Organ Tone, a book that lists the factors affecting the quality and power of a reed pipe. They include thickness of tongue, curve of tongue, shape of the shallot, length of orifice, shape of orifice of the shallot, area of boot hole, length of boot, material of tube, and bleeding the boot. The vocabulary alone—a dialogue between Eros and shoe making—was enough to defeat me. Beyond such tubes and orifices, though, the art of an organist is always one of creative adaptation. A flautist, a trumpeter, a violinist can carry her instrument around with her—Yo–Yo Ma once left his Stradivari cello in a New York taxi—but each pipe organ is immobile and unique. An arrangement of stops that produces reworks on one instrument may fizzle on another.

This has been so for hundreds of years—organs have a long and complicated history. Start with some basic pan pipes, add a box to rest them on, and build a sliding device to control the flow of wind into the pipes: already, you have a primitive version of the instrument my father so adored. The early organ, in truth, is a close relative of the bagpipes.

It seems almost like an admission of guilt. The two most hated instruments in Western music turn out to be cousins. Both of them are wind instruments; unlike pianos, they depend on a reliable supply of air. Once they have such a supply, they can produce a disturbing volume of sound. By the vagaries of history, bagpipes would be relegated to military bands, Scottish country dancing, and the fringes of Celtic folk music while pipe organs would settle down in churches. Yet organs had been hugely important in the development of European music. “What else simplified the scale and fixed it for ever as a single series of octaves?” asked the music historian Peter Williams. “What else gave us the keyboard, and therefore subsequent inventions like the piano? Probably gave us the very names of music’s notes?” For a time, as my father knew, organs had enjoyed high status in the secular realm. In a fourteenth–century Tuscan romance, a blind musician begins to play a portable organ while a thousand songbirds are warbling in the branches overhead. Awestruck, the birds fall silent. A nightingale pays tribute to his human rival by swooping down and perching just above the organist’s head. Then the birds sing even louder than before.

When I imagine my father now, I see him at the organ of the church where he served the longest: St. John’s Cathedral in Saskatoon. Whether he was deploying its trumpet and oboe, its flute and céleste, or any of its dozens of other stops, this organ had a singular purity of tone—in the right hands, that is. No nightingales found their way into the cathedral, although one year there were bats. The console at St. John’s is tucked away behind a pulpit and a stone screen, a few steps up from the long rows of pews. On a Sunday morning, my father would arrive early, changing from his street shoes into a pair he reserved for the organ, donning his blue, ankle–length cassock and a white surplice over top, and checking to see if there were any last–minute changes in the order of service. Then he would stride across the front of the church, stopping to give a cursory bow in the direction of the altar, before sitting down at the organ bench and arranging the sheets of music he would need over the next couple of hours.

My father would set the pistons—buttons that control a prearranged set of stops, allowing for quick–fire changes of volume and tone. Then, with everything ready, he would begin the prelude—a stately work, often by Bach. My father avoided very quiet preludes; they were too easy for the congregation to talk over. Lengthy preludes would send me into a state of fidgeting anxiety in case the priest started the service before my father had finished playing. If the priest interrupted him in midflow, my father would be sure to take offence. He might get his revenge by an act of musical sabotage. For some years, the cathedral had a “family service” that required him to forsake the organ bench for a piano near the congregation and to play a few popular songs in the guise of hymns. I recall the crowd at a family service struggling to keep up with “Blowin’ in the Wind,” my father racing through the song at twice the normal pace, his complexion high, his eyes a gunmetal blank. I was mortified—for my father, for my mother, for myself, for Bob Dylan. How many ears must one man have before he hears people cry?

My father’s sporadic problems with the clergy had ancient precedents. From early in the Christian era, organs have been a target of moralists. Saint Jerome, a Bible translator and supposed lion tamer, gave a fellow believer some firm advice on how to raise a daughter: “Let her be deaf to the sound of the organ.” In the Renaissance, Erasmus was equally severe: “Men leave their work and go to church to listen to worse noises than were ever heard in Greek or Roman theatre. Money has to be raised to buy organs and train boys to squeal.” The backlash against these noises grew even stronger with the Puritans, under whose influence England and Switzerland saw the systematic destruction of organs. In the 1560s, organs were ripped off the walls of English churches and their pipes melted down to make pewter dishes. A century later, in the city of Exeter, soldiers tore out the organs and, it is said, “taking two or three hundred pipes with them in a most scornful and contemptuous manner, went up and down the streets piping with them; and meeting with some of the choristers of the church . . . scoffingly told them, ‘Boys, we have spoiled your trade, you must go and sing hot pudding pies.’”

Luckily, most of my father’s preludes would finish without any clerical interruption. In the ensuing silence, he would improvise quietly on the theme of his prelude, avoiding the booming pedals and using modest string or woodwind stops, the music curling and twining and stopping at a moment’s notice. Then the priest would appear, announcing the first hymn. My father would start to play at a healthy volume, to set a tone of confident praise and encourage the congregation to sing; he would alter the volume of the ensuing verses by using a different set of stops for each, until, eventually, the hymn reached a rousing end.

Such was the natural order of events in my boyhood, Sunday after Sunday, year after year. Each season in the liturgical round brought its own music—Bach’s choral prelude “Wachet Auf,” for instance, is invariably played during Advent, the weeks leading up to Christmas. Yet my father hated to repeat himself. He always liked to try out new works, both for choir and organ, and no two of his recitals had exactly the same lineup of pieces.

Unlike organists who dazzle by means of superficial effects, my father gave close attention to the structure, the inner voices, of each work. A fantasia, for instance, would set out a composer’s main themes and develop them with a rich, owing grace. A fugue would bring in other voices, their interweaving lines taking the music in new directions before tension was resolved in harmony at the end. My father never reached perfection—what artist does?—but he always strived for it. Music, to him, was an act of reverence and homage. Whereas sermons were disposable commodities, Bach was as essential as bread. Music could be prayer; music could be revelation; music could improve the world.

I found an expression of this faith in a slip of paper that I came across after his death. Among the piles of letters, musical scores, concert programs, and church bulletins I discovered a typed quotation from the Hungarian composer Zoltán Kodály. It was, I suppose, Kodály’s credo, and I believe it was my father’s too: “It is the bounden duty of the talented to cultivate their talent to the highest degree, to be of as much use as possible to their fellow men. For every person’s worth is measured by how much he can help and serve his fellow men. Real art is one of the most powerful forces in the rise of mankind, and he who renders art accessible to as many people as possible is a benefactor of humanity.”

My father might have hesitated to resort to such grandiose words. But Kodály’s faith was one that spoke to him. It transformed what might appear like self–absorption into a gift, an act of service. He tried to maintain this faith to the end of his life, sometimes against heavy odds.

From the book The Organist: Fugues, Fatherhood, and a Fragile Mind by Mark Abley, copyright © 2019. Reprinted by permission of University of Regina Press.