This article is also available to read in Cree.

“Tansi, today we are going through some random phrases,” Julia Ouellette says to the camera. She holds up slips of paper with English words while repeating the Cree translations quickly and then slowly. “tantahtwaw,” she says, holding a paper that says “how many,” emphasizing each syllable. “tantahtwaw. Repeat after me.”

Ouellette, a grandmother from Makwa Sahgaiehcan First Nation in Saskatchewan, posts Cree-language videos regularly on TikTok, where she has more than 16,800 followers. The videos are casual, with a simple formula: Ouellette, in glasses, with her hair tied back, offers viewers a few Cree words or phrases to practise aloud. In both languages, her voice has the distinct quality of a Cree speaker: rich and resonant, her “r”s and “l”s—consonants not found in Cree—are especially pronounced when she speaks English. A former language teacher at Big Island Lake Cree Nation in Saskatchewan, she started posting videos on TikTok in 2020 that included such COVID-era phrases as “wash your hands” (kasichiche) and “get away” (awas), along with more cheerful ones, like “Merry Christmas” (miyo-manitowi-kîsikanisi). Ouellette never writes out the Cree words or phrases, instead instructing the viewer to repeat what they hear.

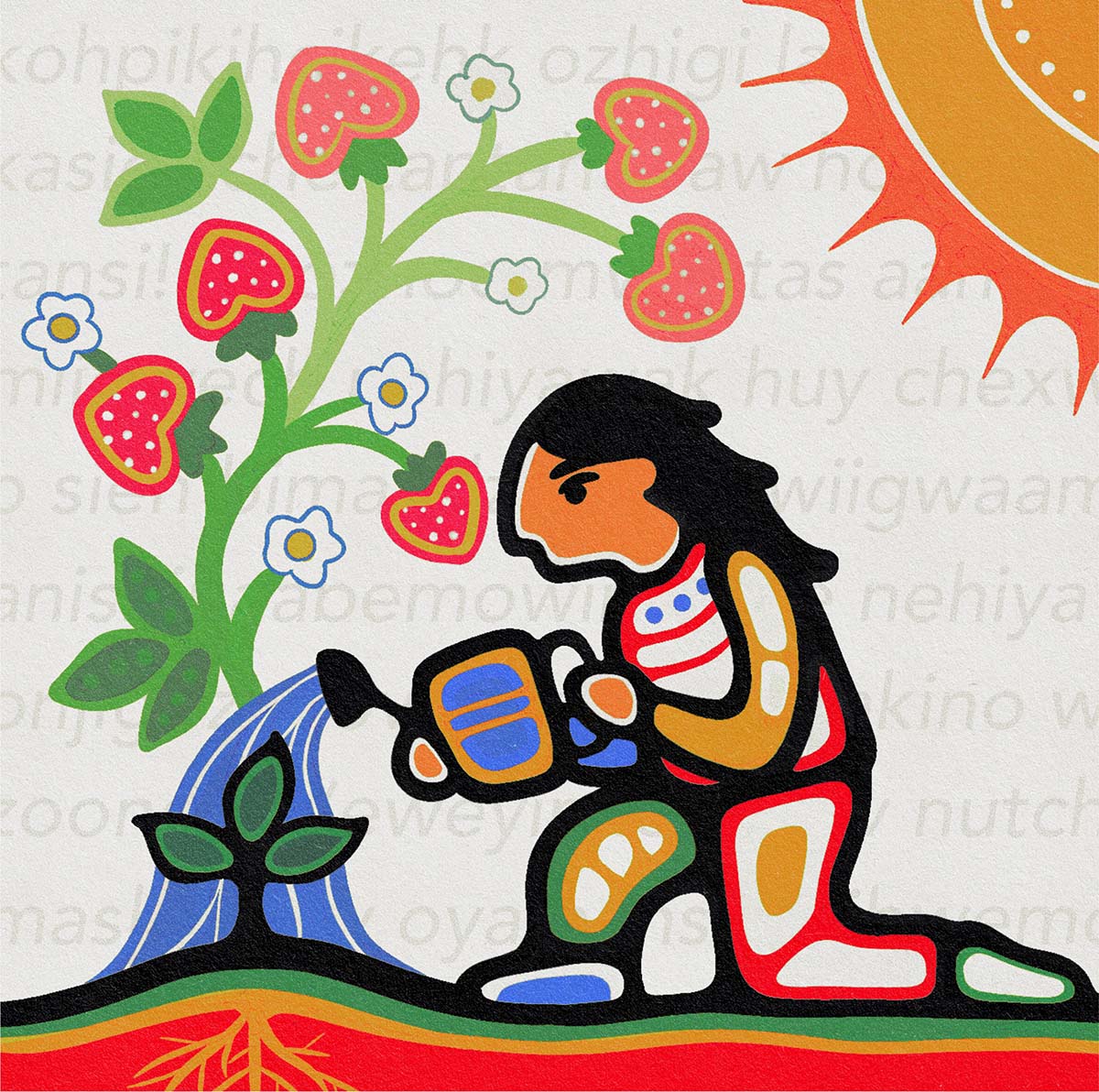

Ouellette is part of a growing community of Indigenous-language speakers using social media as a teaching tool. James Vukelich Kaagegaabaw, a descendant of Turtle Mountain, shares an Ojibwe word regularly with his 135,000 Instagram followers. Jonathan Augustine, who goes by RezNeck Farmer on TikTok, shares Mi’kmaw lessons along with folksy videos about gardening. Zorga Qaunaq, under the username Tatiggat, posts on TikTok about daily life, beading, and Inuit culture, alongside how to properly pronounce words like “Inuit.”

In what is now called Canada, there are hundreds of Indigenous communities and more than seventy Indigenous languages. Each language has been imperilled by colonization and Canada’s legacy of forcible assimilation. In residential schools, children who arrived knowing only their mother tongue were often beaten for speaking it until they learned English or French. Many survivors lost fluency in their language; they also lost the ability to communicate with their parents and Elders and the opportunity to pass language down to their children.

A few Indigenous languages spoken in Canada are robust and stable—including Inuktut, Cree, and Anishinaabemowin, each of which comprises several dialects—but many have only a handful of elderly speakers left. Even though UNESCO today considers three quarters of Indigenous languages as endangered, even though some languages have dwindled to just a handful of fluent speakers, there is tremendous reason for optimism.

The author and artist Eden Fineday writes that the Cree word “awâsis” is commonly translated as “child,” but what it really means is “a sacred gift on loan from Creation, for you to raise on behalf of Creation.” Each word carries thousands of years of history and meaning, beyond simple translation. Linguists use the term “language family,” which evokes the way the connections and relationships between distinct languages can be mapped like a genealogy; in this way, they are our ancestors and, if we carry them forward, our descendants. If a language disappears, an entire world is lost too.

For decades, an alarm has been sounding about endangered languages. In 1992, American linguist Michael Krauss published “The World’s Languages in Crisis,” which anthropologist Wade Davis declared “one of the most disturbing scientific papers ever published.” In the paper was an oft-cited dire prediction: as many as 90 percent could eventually disappear. “Many linguistic field workers have had, and will continue to have, the experience of bearing witness to the loss, for all time, of a language and of the cultural products which the language served to express for the intellectual nourishment of its speakers,” Krauss wrote. But, more recently, there have been bright lights. Squamish, or Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Sníchim, had only ten fluent speakers left in 2010. Since then, there has emerged an adult immersion program, a Language Nest for infants and toddlers, and an Instagram account that posts Sḵwx̱wú7mesh-language lessons. Today, there are more than a hundred speakers.

Never before have Indigenous nations and communities had so many tools for revitalizing their languages. Nuxalk, a Salishan language spoken in Bella Coola, on the central coast of British Columbia, is spoken fluently by only a few. But children are learning Nuxalk at an independent school run by the Nuxalk Nation. Since 2014, the local radio station has hosted Nuxalk programming, and in June, it released the first ever studio album of Nuxalk music. FirstVoices, an online Indigenous-language platform, offers stories, songs, and word games in Nuxalk and an app that allows one to text, email, and use social media in the Nuxalk alphabet.

Apps and social media remove one of the main barriers for many aspiring speakers: proximity. It’s hard to learn your language if you don’t live on your homeland, and while figures vary widely by region, according to the 2021 Government of Canada census, First Nations people who live on reserve are about four times more likely to know an Indigenous language than those off reserve. Living in Vancouver, I rarely hear Cree spoken in my daily life. I have Cree dictionaries, books, vocabulary sheets, and a word-of-the-day calendar—and for a long time, I thought if I just looked at the words long enough, the rest would come.

Cree is Ouellette’s first language, spoken at home by her mother and grandmother, and she learned to speak the way all babies do: by listening, then practising, the sounds gradually cohering into association. When she started out as an education assistant in Makwa Sahgaiehcan, she copied the previous instructor’s writing-focused methods. She would tell students how to say a word, then ask them to colour the word on their vocabulary sheets. Then one day, she called out a hello to a student by the canteen: tansi! The student responded by counting to three and saying that was all she knew. “And I thought—Oh my god, is this what I’m doing to these students?” Ouellette says. They could identify words, write an answer to a question, but not respond in conversation. From that point on, she forbade paper or pen. Instead, she taught orally, developing the method she still uses on TikTok: flash cards, repetition, emphasizing consistency and practice, and mastering one word at a time. “When we were born, we learned how to speak before we could write,” she notes. We might say “mama” hundreds of times before we pick up another word.

Any unfamiliar language is intimidating in its written form. The anxiety about mispronouncing a word aloud seems nearly universal, particularly in English, one of the most unruly and unpredictable languages that’s rife with confusing words like “epitome,” “inchoate,” and “Wednesday.” When people complain that an Indigenous word or name is too difficult for them to say, what they mean is that it’s unfamiliar. The reason we look at the written words “daughter” and “laughter” and know they’re pronounced very differently is not that they’re easier or more logical but that we’ve heard them pronounced many times. The problem is not the writing but the lack of speaking; the solution is to practise. Repeat after me.

Like me, John-Paul Chalykoff wasn’t raised with his ancestral language. A member of Michipicoten First Nation, he grew up in the nearby town of Wawa, Ontario, where his parents and siblings spoke English at home instead of Anishinaabemowin, the Ojibwe language. But when he was ten or eleven, a trio of fluent speakers, including Howard Webkamigad, a language teacher at Algoma University in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, visited Michipicoten to offer the community a week-long language course. It was a spark for Chalykoff; he’s now thirty-seven and a professor of Anishinaabe studies at Algoma, the only university in Canada to offer an undergraduate degree in Anishinaabemowin.

Chalykoff’s approach to language learning is different from Ouellette’s, reflecting his acquisition later in life. As an adult, despite years of study and practice, he found himself stalled. Finally, an adult immersion program that combined conversation with grammar lessons shook something loose. Anishinaabemowin, like Cree and Inuktut, is a polysynthetic language, where a single complex word can represent the equivalent of an entire sentence in English (for example, “maajibiisaan” means “the rain is starting”). Understanding the mechanics of a language is more complicated. “I’ve seen a lot of immersion programs where people are told to listen, and they could do that for years and still not fully grasp it,” he says. “But when you start seeing those key patterns, that’s when you begin to catch a little more each time.”

The barrier that Chalykoff works to overcome, in himself and his students, is fear. It’s the same fear that causes Canadians to flinch when they see a street renamed in an Indigenous language, the same one that causes even a familiar greeting like “tansi” to stick in my throat when I’m talking to an Elder. “Some of those Ojibwe [Elders] who were teaching, they could be pretty mean—and [some students] didn’t want anything to do with the language after, because they were made fun of for the way they spoke,” Chalykoff says. Getting things wrong is part of the journey, he adds, but encouragement is crucial.

So, too, is exposure. The past few years have seen a number of Indigenous-language film projects, including the 2021 Cree thriller Night Raiders, a Comanche-language dubbed version of the 2022 alien blockbuster Prey, and the 2000 animated movie Chicken Run dubbed into Mi’kmaw by a couple from Eskasoni, Nova Scotia. This August, Anishinaabemowin-dubbed Star Wars (Anangong Miigaading): A New Hope premiered. Chalykoff voiced Luke Skywalker’s uncle.

MANY ANTHROPOLOGISTS have studied and transcribed Indigenous languages, treating them as scholarly subjects or cultural curiosities—an approach distinctly for the benefit of academics, not the speakers themselves. Frank Siebert, a self-taught ethnographer, authored a dictionary of Penobscot after hiring the tribal nation’s speakers as his research assistants. When he died, this intellectual property eventually ended up at a non-profit society in Philadelphia, which now holds the copyright; Penobscot people must get institutional permission to access it. In the absence of conversation, a record of a language is a kind of obituary; we breathe life into languages by speaking them, no matter how rudimentary or tentative our efforts.

In 2019, the federal government passed the Indigenous Languages Act, promising to provide “adequate, sustainable and long-term funding for the reclamation, revitalization, maintenance and strengthening of Indigenous languages.” The act was in response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action, which stressed that these languages were fundamental, invaluable, and in urgent need of preservation, and which called for the appointment of a commissioner of Indigenous languages. A commissioner was appointed in 2021, and $333.7 million was committed over five years, directed to Indigenous governments and organizations for language programs. Three hundred and seventy-two communities received funding in 2020/21. This boost in support has bolstered the efforts of many nations to nurture new speakers, including Nuxalk and Squamish, whose language initiatives have received federal funding. In BC, the First Peoples’ Cultural Council reported a 20 percent increase in Indigenous language learners between 2018 and 2022.

The funding provided by the federal government for Indigenous languages is crucial, but dwindling. The 2024 budget allocated around a third less than in 2019. In a press release, the FPCC wrote, “Providing a comparison to the $225 million committed over five years for all the country’s Indigenous languages—the original languages of this land—is the $4.1 billion allocated by the Federal Government on-going and in prior budgets for official languages support.” For example, in May, the French immersion school in Iqaluit celebrated the completion of a $32.9 million upgrade, funded by the federal and territorial governments, to serve students from kindergarten through grade twelve. Though many more children in Iqaluit speak Inuktut, an official language of Nunavut, there is no Inuktut-language public school for them.

The situation underscores the fact that Canada does not yet see Indigenous languages as equally valuable. The effort to carry them forward is still propelled by speakers, who pass the language between one another like a baton. “I always tell my [university] students you’re going to experience culture shock—which feels weird to say, because you’re an Indigenous student learning your own language,” says Chalykoff. “Suddenly you’re feeling angry, or you want to cry. I think some come into it thinking that blood memory will kick in. And most of us wish it did, but it’s going to be hard work if you really want to get there.”

But the work itself is simple: one word at a time. “It’s never too late. As long as you have it in your heart that you want to learn your language, you can do it,” Ouellette says. “Just keep speaking it. Every day.” She ends her videos with “kisahkitinawaw” (I love you all), “miyo kisikansi” (have a good day), and “mwestas” (see you later). There is no “goodbye” in Cree.