If and when Orillia becomes “Toronto’s Banff”—as its most ambitious civic boosters hope—local historians may well trace its transformation to a small, unprepossessing cube of a building tucked away in a neighborhood that, like not a few in this small city of abandoned factories, has seen better days.

The cube belongs to Charles Pachter, known to many Canadians as the artist who created those full-scale moose sculptures that proliferated from coast to coast a decade ago. His best-known works hang in the Portrait Gallery of Canada, Parliament, 24 Sussex, the Canadian Embassy in Washington—and, since last year, in this building he’s dubbed Moose Factory of Orillia (a.k.a. MOFO). Pachter is perfectly at home exchanging air kisses at chic Toronto gala fundraisers. So what’s he doing setting up shop on the northern tip of Lake Simcoe?

“There are thousands of fancy summer cottages around these parts—but the people who own them often treat this historic town as flyover country,” Pachter says as he serves me legendary Wilkie’s butter tarts at MOFO. “I used to just speed through on my way to my summer studio on Lake Simcoe. Most of the time we’d show up here to buy food and go to the Goodwill.”

But over the course of all those shopping trips, Pachter started making friends in Orillia. He became involved in local charity drives, and donated his paintings to help raise funds for the refurbished Orillia Museum of Art & History in the heart of town. As a seasoned real-estate entrepreneur who’d been repurposing derelict properties in Toronto for decades, Pachter began thinking about Orillia’s potential. He started studying the local housing market. And when he found an old car repair shop he liked on a little-known slice of Western Avenue right downtown, he bought it for a song. (The same goes for everything inside. “See that couch over there? ” Pachter asks me. “Thirty dollars at Goodwill. It said sixty on the price tag, but they gave it to me for half-price because it was seniors’ day.”)

I’ve come to visit Pachter’s new studio because he’s a great Canadian artist—a man who walks that fine line between creatively reinterpreting iconic national images and satirizing them with affectionate mischief (see, for example, his 1972 painting, Noblesse Oblige, featuring the Queen riding a moose). But there’s a larger story here, too: Pachter is hardly the only Torontonian who’s become exasperated with the city’s traffic and exorbitantly expensive real estate. (The average price of a detached family home in Toronto is now about $700,000). In coming years, as more and more Hogtown knowledge workers gain the ability to telecommute from anywhere, they increasingly will flee to outlying Golden Horseshoe communities such as Barrie, Caledon, Collingwood, Hamilton, Peterborough, and Guelph. Charlie Pachter is doing his best to make sure Orillia gets its fair share of the action.

As with many towns in this part of Ontario, Orillia once was a hub for assembly and manufacturing jobs. Some of those operations still remain. But the largest local employer now is Casino Rama. The town’s waterfront (spanning two lakes, Couchiching and Simcoe) attracts boaters and tourists in the summer, and there is some skiing in nearby Moonstone and Mount St. Louis. Yet much of the Toronto money that trundles into the region every summer weekend in upscale SUVs funnels south into Lake Simcoe, north into the Muskoka lakes, west toward Collingwood and Thornbury, and east into Kawartha Lakes. Orillia is betwixt and between.

As Pachter tours me around town in his minivan, he points out sites connected to the city’s famous sons and daughters: Stephen Leacock, Gordon Lightfoot, Glenn Gould, Group of Seven painter Franklin Carmichael, sculptor Elizabeth Wyn Wood. It’s a gritty city that successful people usually leave in order to further their careers. Aside from a few gilded pockets, there’s a distressed quality to it. Not quite a teardown overall, but definitely a fixer-upper.

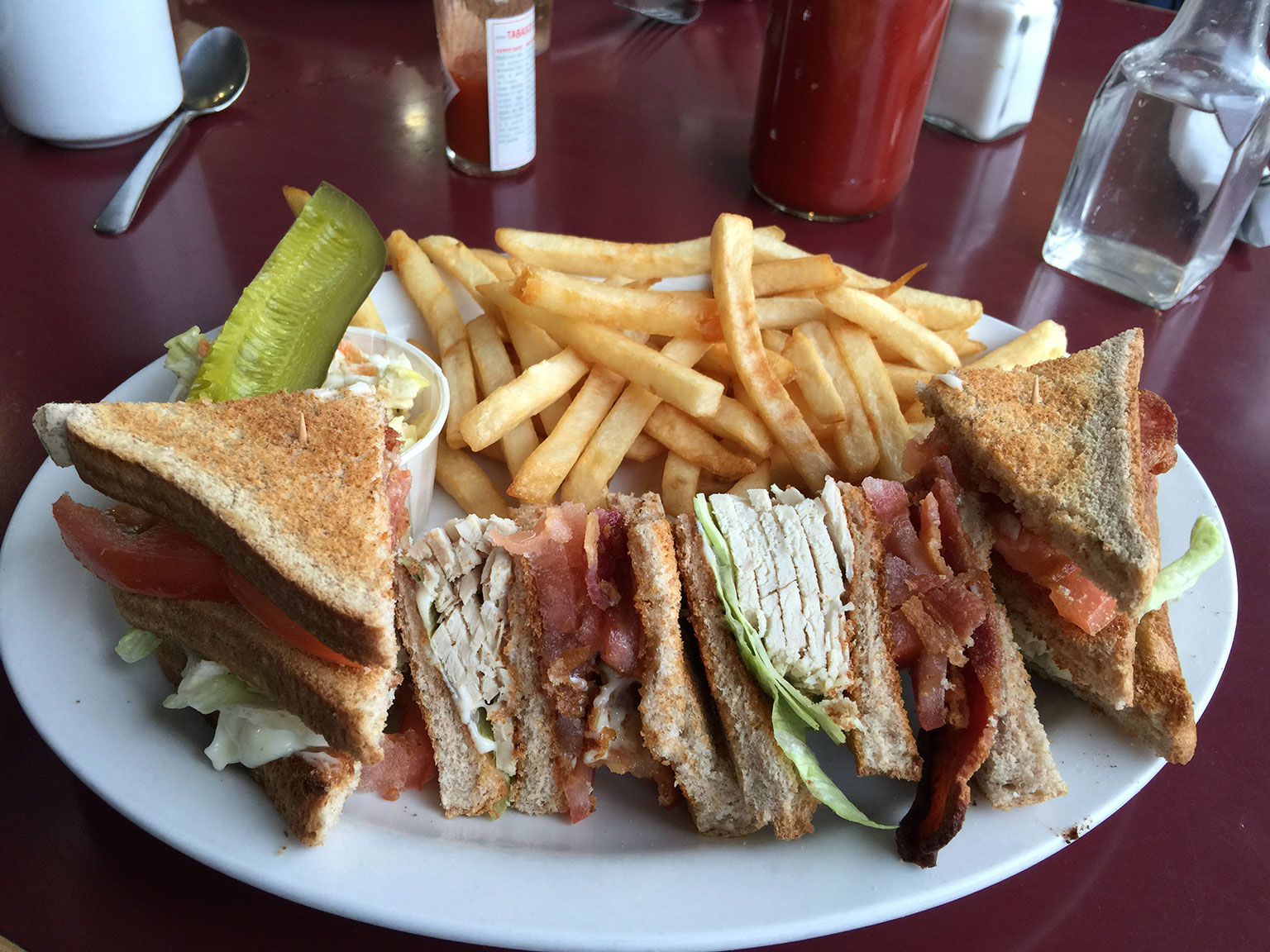

Nevertheless, Pachter is bullish. “You can buy a six-bedroom mansion here on a 250-foot-deep lot for $450,000, or a smaller house for $150,000,” he says over club sandwiches at a local diner called Rombo’s. “The local trades are highly skilled, honest, hard-working, and you can renovate a property for a fraction of what you’d pay in Toronto.

“Many of the handsome brick-and-wood buildings date from the mid- to late-nineteenth century, and are eminently salvageable,” he adds. “If you look at the architectural vocabulary, Orillia has the same vibe to it as, say, Woodstock, Port Hope, or [Niagara-on-the-Lake]. But there is still a leftover industrial feel to it. They haven’t found a replacement for the abandoned factories to draw people and money in. Culturally, their greatest success has been the Mariposa Folk Festival [which celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 2010].”

The creation of MOFO is one of the many small seeds of contemporary culture that could help Orillia sprout a new identity, and shed its gritty post-industrial stigma. But for that to happen, Pachter believes, it needs something bold and ambitious to turn the city into a cultural destination. His model, inspired by Alberta’s Banff Centre, is a world-class conference facility that—in his expansive vision—could become one of the largest arts and creativity incubators on the planet.

That vision is what brings us to the main attraction on our tour—a 300-acre cluster of over forty institutional buildings situated among rolling hills, meadows, and old growth forest, fronting 1,500 metres of pristine Orillia waterfront. Some of this picturesque jumble has been converted into office space and courts for the provincial government. But old-timers know the complex by its former identity: the Huronia Asylum for Idiots and Feeble-Minded (yes, that was its actual name), or, in shortened form, “the Asylum for Idiots.”

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, many of the province’s mentally challenged residents spent their entire lives on this campus, some ending up in unmarked graves after enduring years of abuse and neglect. The facility was closed in 2009 amid class-action abuse litigation, though by that time it had long since changed its name to the Ontario Hospital School, and then the Huronia Regional Centre.

“This place is haunted by the memories of wounded people,” Pachter says as we drive around the grounds. “We need to turn it into something new while acknowledging and honouring its past.” He envisions a centre for arts, culture, and digital technology—“a place where creative people from all fields would collaborate, connect, and create.”

We stop, at random, in front of a building set in the middle a picturesque field—a charming 1840s fieldstone farmhouse converted into a residence for institute staff.

“Imagine this place becoming a home for visiting artists-in-residence, or a tea house,” Pachter suggests. At other locations on campus, he points out likely spots for a music pavilion, a sculpture foundry, a botanical garden, rehearsal halls, studios, outdoor concert venues, art camps, and writers’ retreats.

As for the lakeside frontage, Pachter believes it easily could accommodate condominiums, inns, and conference centres. His imagination is boundless, and every turn in the road brings new ideas spilling forth. “The kitchens here used to produce 3,000 meals a day,” he gushes. “Why not a cooking school? A folk music hall of fame? Seniors residences? A film centre connected to TIFF? The potential is tremendous.”

Pachter’s proposed Banff-ification of the Huronia Regional Centre is something of a long shot. It would require enormous private-sector support from corporations that may not yet associate this part of south-central Ontario with high-tech incubation, not to mention the supporting partnership of the Ontario government (which currently owns it). Even then, the planning and construction likely would take several decades. Pachter, who is seventy-two, acknowledges that he probably won’t see it come to full fruition in his lifetime. But he has begun to enjoy this quintessentially Canadian small city, and he wants to do his part to put it on the radar of Toronto’s real-estate exiles.

Our last stop at Huronia is the waterfront, where a collection of abandoned wooden cottages dots the shore. This is where the “feeble-minded” residents would swim, and the staff would come to relax on weekends. There is a beached dock and rusted swings, as well as a wooden gazebo in somewhat decent shape. All of this is fenced off from the public—we are the only souls within shouting distance on one of Ontario’s most picturesque municipal lakefronts.

It is peaceful and unspoiled, but also somewhat sad. The wards of Huronia are long gone, and this city awaits something wonderful to take their place.