The pages had been folded inside a no. 10 envelope and left on the porch of my childhood home. There was no return address or sender: just my name, written across the envelope with a ballpoint pen. It was July 4, 2015. I was visiting home, in Victoria, for the second time since moving to England. I unfolded the contents, my eyes darting to the name at the bottom of the page. It was signed by our neighbour Lynne.

Lynne had lived up the hill for as long as I could remember. Or, rather, she lived across the road and up a steep driveway. I had always felt warmly toward her and her husband, Hans, the only man on our block, aside from my father, to wear a beret. I didn’t know the couple well, though they were part of what my dad had called, with wry affection, “the voisinage,” a rotation of neighbours who hosted unpretentious dinner parties.

I started reading Lynne’s note, expecting to find an invitation or reminder—something ordinary.

I am writing to pass on a couple pages of writing from a friend of mine who was murdered in the Yukon in 1992, it began. To the extent that my attention had been open to the house around me, noting the people and ambient sounds, all my focus now funnelled to what I was reading.

Her name was Krystal Senyk.

Krystal had been best friends with a woman named Colleen, the letter explained. Colleen’s husband, Ronald Bax, was a wilderness guide, sculptor, gun aficionado, and father to their two sons. He was also controlling, jealous, and unstable, the letter continued.

When Colleen decided to leave her husband, Krystal offered her and the boys her support. Ron had resented Krystal for years—he perceived her as a rival of sorts. By February 1992, his rage was getting more pointed and direct. Based on his intimidations, Krystal was starting to fear for her life. She reported his behaviour to the police, but her requests for help resulted in no action.

On the night of March 1, Krystal returned to her cabin in Carcross. Ron was waiting and shot her in the doorway to her house. When she didn’t show up for work the next day, her colleagues called the police. Between Krystal’s murder and the discovery of her body twelve hours later, Ronald Bax disappeared.

To this day, he has never been found.

My neighbour Lynne had worked with Krystal at the federal land claims office in Whitehorse. In the days following the murder, a colleague discovered some personal writing on Krystal’s work computer. Lynne didn’t know why, but the colleague printed the pages and gave them to her. That summer of 2015, while cleaning her home office, Lynne had unearthed them again.

I am handing them to you, in case you find them at all useful in your writing, she wrote in her note to me. I know this is quite presumptuous, but your name kept popping into my head.

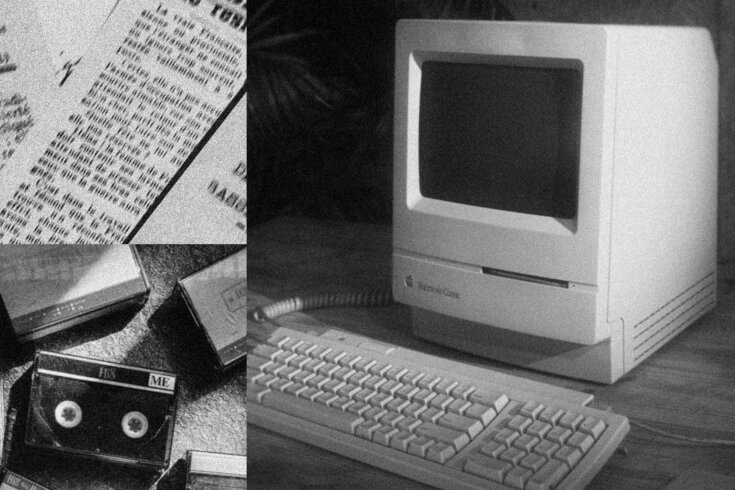

There were only two pages, stapled together in the left-hand corner. At the top of the first page, Lynne had printed “KRYSTAL” in capital letters, underlined twice. Below her name, the years of her life: 1962–1992. Next to it, the following annotation: Krystal Senyk murdered on March 1, 1992 by Ronald Bax in Carcross, YT. Today, the pages are thirty years old: faintly yellowed, the text typed in 12-point Courier.

I am the collective gathering of all my experiences. My behaviours and beliefs have evolved throughout countless ages and have currently choosen to manifest themselves in the human form present on this earth, in this time. You see, i am part of a continuum. A linkages of lives each unique unto itself but forming a complete picture of the essense of the life it was and currently is.

I found myself searching for an explanation—as if Krystal herself could tell me, through these words, what had happened to her. Her sentences felt, instead, like the opening of a well. Her voice had a rawness about it: fresh, instant, unmediated, as though composed in one chain of thought. Yet the writing was dense. At first, I found it impenetrable.

I read the pages two or three times. Then I folded the papers, very carefully, back into their envelope. I sensed that I couldn’t shift my attention to Krystal’s story until I could devote my whole, unbroken focus. Over the next three years, I would reread the contents of the envelope, removing the pages with equal care—less to avoid crumpling and more because I perceived in them something very dear: a call, a seed, an urgency. So dear it immobilized me.

In that time, I googled. While the murder had attracted local media frenzy in the 1990s, little of the case could be found online by 2015, aside from the RCMP’s wanted advisory for Ronald Bax. I also discovered one or two articles that had been digitally archived: the first, published the day after Krystal’s death, on the front page of the Whitehorse Star. “Woman Is Shot,” the headline announces. “RCMP Hunt for Murder Suspect.”

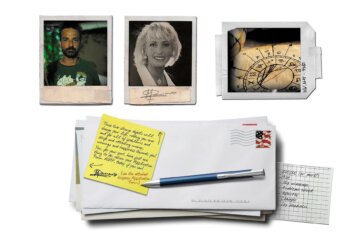

Online, two images sit side by side. First: Krystal at her desk, before an ordered jumble of papers and a coil notebook, pen in hand, buttoned V-neck cardigan with a scarf tucked into the collar, hair curling around her ears, mouth flat. A lightness in her gaze suggests the camera shuttered between smiles or a roll of the eyes as she waited for the photographer (a colleague, I imagine) to finish. Behind Krystal, three photos hang on the wall, maybe images she snapped herself. Two appear to be night scenes, one with a burst of luminosity I can’t decipher from this distance, though it’s moon like. On the shelves, there are two potted plants and a puppet slumping against a stack of papers.

The other photo is of Ronald Bax: his eyes so resinous you can’t discern his pupils. His chin is clean shaven, but he has a blond moustache, thicker than the hair on his head, which appears thin or thinning. I note the mole on the left side of his throat. The Whitehorse Star describes Bax as five feet nine inches, though the RCMP lists him as five seven. I can see that he is good looking.

In the early days of writing this book, when I googled “Krystal Senyk,” the search engine returned more images of Bax. When Krystal did appear, her image was often yoked to his: a tiny injustice I would register as I took a screenshot and cropped him out of the frame.

The website I didn’t stumble upon, because it didn’t exist yet, would belong to former journalist Myles Dolphin: www.whathappenedtoronbax.com. On July 4, 2018, three years to the day that my neighbour introduced me to Krystal, Myles reached out to me over Instagram. He’d seen a tweet I wrote to a reporter who had written one of the few recent articles about the murder. The reporter had quoted from an interview with Krystal’s mother, Vera Campbell. I had wanted to know if any further interviews existed. This reporter no longer worked at the Whitehorse Star, and the paper didn’t have a forwarding address for him, but I learned that Myles had also interviewed Krystal’s mother while he worked at Yukon News in Whitehorse. He’d had this story “to the side of his desk” since 2015, like I had. His website, which he’d launched the month before contacting me in 2018, is an impressive collage of all the research he has collected on the case and which we would continue to gather as a team.

When Myles spoke to Krystal’s mother in 2016, Krystal had been dead for twenty-four years. In that time, Vera had been updated less frequently by police. Krystal’s father, Philip, had regularly checked in with the investigation, but Vera’s interactions with police had been less cordial. In her own words, nothing was good enough for her back then. She was too angry. “The fight would start,” she said, “and they’d argue with me, and I’d argue with them. We never got along, so they stayed away from me.”

Vera and Philip had separated when Krystal was a child, and they weren’t on speaking terms. When it came to the investigation, Vera was out of the loop. By the time she spoke with Myles in 2016, it had been years since the story had last been in the media. Yet she felt certain that Bax was still out there.

“After all this time, something’s gotta be done. Because he’s there,” Vera said. “You can’t just turn it aside because it’s not kosher.” She stressed that Myles could call her any time. “If I’m here to answer the phone, it doesn’t matter. Any time, in the middle of the night, if you get a whim or a thought, you want to talk about it, you can call. I’m so happy that you’re going to do something.”

Maggie Nelson’s book Jane, published in 2005, orbits the then unsolved murder of her aunt Jane in the 1960s. When Nelson wrote Jane, her aunt’s case had remained cold for thirty-five years. Krystal’s case has now been open for thirty. Most memories of her are older than I am. Perhaps every book about murder is an exercise in lateness, because our attention didn’t arrive soon enough. If it had, there would be no murder and no book—a preferable, if self-obviating, conclusion. This book and Krystal could not coexist, no more than Jane and Nelson’s aunt Jane.

In one of the first poems, titled “Figment,” Nelson’s grandfather asks of her book in progress:

What will it be, a figment

of your imagination?

In this question, he pinpoints the task, and the impossibility, of narrating a real-life story that lacks a real-life ending. How do you stitch together a person you can’t talk to—who died before you were born (or, in my case, when I was four)? How do you do justice to her or to the real-life trauma that has nothing, really, to do with you? It’s a funny phrase, “do justice,” like we might “do laundry” or “do the ironing.” The expression means to treat fairly, with full appreciation. Often it has nothing to do with justice. Except, in this case, it does.

Years earlier, at the end of my undergraduate degree, I volunteered at a women’s transition home in Victoria. I cleaned. I washed laundry. I sorted the clothing donations. I cared for the children when their moms needed to focus on other tasks. One day, I recognized a new resident who came in. We’d gone to high school together. It struck me then—the pervasiveness of intimate partner violence. How ordinary it was, if gobsmacking in its cruelty. I was trained not to acknowledge recognition when it happened. If you saw a former resident on the street, you didn’t stop and ask how they were. I respected why—it preserved privacy and safety. But there was something eerie about this pretending. How everything about intimate partner violence seemed to unfold in sealed, unspeakable quiet. When she entered the living room, we held each other’s gaze. She smiled uncertainly. Neither of us said a word about high school. Her daughter was two years old, and I busied myself with her care.

A decade later, I called this same transition home as I tried to support someone close to me. This person had confided in me for months, texting sometimes in the middle of the night when the abuse reached a flashpoint. I didn’t know what to do. I felt scared for her and useless. Again, the silence struck me. My friend didn’t want outside help, though I gave her the transition home’s number just in case. Not for the first time, I found myself in an underground system of women talking to other women, or women warning other women—never in public. Rarely trusting outside authorities to intervene. How many people were in this situation, keeping the violence wilfully, resignedly quiet?

When I read my neighbour’s letter in 2015, it churned something in me. Even when I had to focus on other tasks, Krystal’s story roosted in the corner of my consciousness, rustling its feathers now and then, spiriting me toward two impossible missions:

1. I wanted to find Krystal Senyk.

2. I wanted to find Ronald Bax.

Even though I recognized these goals as unattainable in a material sense, they consumed me. I have tried to reach Krystal. The fragments of her preserved in photos, video, newspapers, memory—I tried to gather them, to fix them in place. I was the same age as Krystal when she died, and that coincidence meant something to me. It felt urgent to understand what had happened to her, to “make sense” of her murder. And if her murder had no “sense” to it, I wanted to demonstrate the consequences of dismissing a person’s fear, of thinking this violence is private or none of our business. I wanted to make this violence our business.

And yes, I hoped to find Ronald Bax. I could say that I desired that resolution for Krystal’s family—and I do. Very much. But it has become more personal than that. For reasons I don’t fully comprehend, because I don’t experience them intellectually—I experience them in flushes of heat, gastric acid, and hives—I want to see Ronald Bax on trial.

In the summer of 2018, three years after I learned about Krystal’s murder and a month after I began collaborating with Myles, I visited home in Victoria again. I sat with Lynne, on her patio, which overlooks the house I grew up in. Lynne had found for me a mixtape that Krystal had given her in the early ’90s. Inside the case, Krystal had hand-painted a J-card with blue and iris smudges. She’d printed the title of each track in two columns, one for each side. On the tape’s adhesive label, which faced out through the plastic, she’d inscribed: I got a name. I later realized this was the title of the first track on the B-side, a Jim Croce song released in 1973. At that moment, however, I mistook the words for Krystal’s own title for the cassette. Written in her own hand thirty years ago, it felt like a dispatch from back then—a call.

Excerpted from I Got a Name by Eliza Robertson and Myles Dolphin. Copyright © 2023 Eliza Robertson. Published by Hamish Hamilton Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.