“Let it wash over you,” the man says. “Like body surfing, let the waves take you. Don’t try to touch bottom, and you won’t hit the rocks.” A burly guy with a voice like timber, Nigel Spencer is sitting at my kitchen table, talking into my tape recorder, addressing my despair. Weeks into this article about one of Canada’s most celebrated writers, a woman whose name is spoken with reverence in literary circles, whose books inspire a steady flow of commentary, and I still can’t get past the first page of her latest novel. Is it possible Marie-Claire Blais could be—as great minds have proclaimed—a genius, and also be unreadable? Or is it me?

Spencer’s translation of Naissance de Rebecca à l’ère des tourments will be published by House of Anansi Press this fall as Rébecca, Born in the Maelstrom,Blais’s twentieth novel and the fourth in an ambitious series launched a decade ago with Soifs (meaning “thirstings,” translated by Sheila Fischman as These Festive Nights). A vast fresco involving some 100 characters, the series has received dithyrambic reviews: “The Divine Comedy of our time,” proclaimed Le Devoir. The Globe and Mail opted for “a modernist masterpiece,” and a prominent French critic drew parallels between Blais and Virginia Woolf.

Both Soifs and Rebecca won Governor General’s Awards for French-language fiction, adding to the very long list of prizes and honours bestowed over the past fifty years on a demure Catholic school dropout who was twenty when her first novel, La belle bête, caused a literary sensation in 1959. Published a few months later in English as Mad Shadows, this slim Gothic twist on the idea of the Beauty and the Beast was hailed—and reviled—as a critique of Catholic Church–dominated society, an exposé of mind-body bifurcation resulting from religious orthodoxy. Many of the main themes of Quiet Revolutionary literature soon to be born were present: absent father, suffocating family, the creative soul struggling and failing to be free. If, half a century later, La belle bête fits more surely on the shelf with Edgar Allan Poe than in the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, it remains a reliable introduction to the vast Blaisian oeuvre that followed, in addition to the novels a slew of plays, books of poetry, diaries, and essays. Still, a strikingly original tale told with confidence and verve, though what it means is hard to say. “Meaning? ” Blais’s long-time friend and publisher Barry Callaghan barks when I raise the subject. “Please remember what Susan Sontag said: be careful talking about meaning in literature. It’s always one step away from sociology, the lowest form of measurement.” Over the years, Callaghan’s small press, Exile Editions, has faithfully kept Blais’s early works in print even as she drifted into the prestige category for mainstream publishers. Although sales of her books range from modest to minuscule, there is no doubt in Callaghan’s mind that Marie-Claire Blais is one of Canada’s pre-eminent talents.

“A writer totally in touch with her voice, at the top of her game,” he insists. “She’s a supreme stylist. A writer like no other writer this country has produced. She will be remembered for the total authenticity of her vision.” That she isn’t in everybody’s bedside reading pile in either official language Callaghan puts down to the creeping “domestication” of literature. “People don’t read Marie-Claire because she’s too tough, too good.”

“She’s a monument,” says her Quebec publisher, Jean Bernier, of Éditions du Boréal. Nobody dares criticize her. As I make my way through the Quebec literati, people who know and revere her work, I find few except reviewers who’ve read the recent novels. Despite a brisk academic interest, Anansi expects to sell no more than 1,500 to 2,000 of Rébecca across North America. “She’s one of those writers who’s almost canonical,” says the Toronto firm’s publisher, Lynn Henry. “There’s a prestige involved in publishing her. We’re very aware of her status. I wish she could be a bestseller, but she isn’t.”

When I ask about her own experience reading Rébecca (which she also edited), Henry pauses. “You do have to let yourself go. It’s not a book you can pick up and put down. At the end, I wept, for a combination of reasons, I guess—the effort of reading and the reward. She presents the largest imaginable sense of humanity, a sublime vision of how the world works. There aren’t many writers working at that level.”

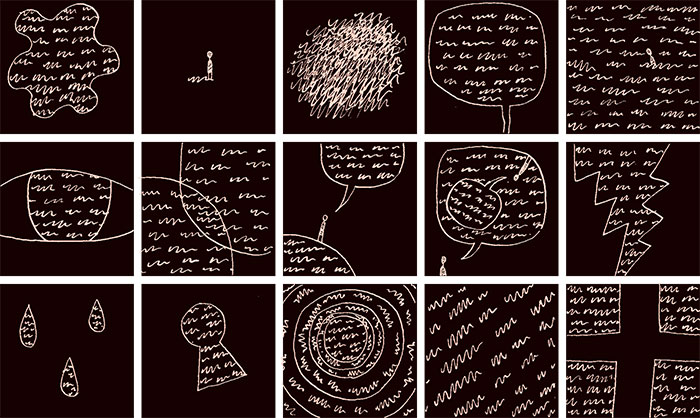

I pick up the second volume in the series, Thunder and Light, translated by Spencer. The first sentence of the first page starts two-thirds of the way down with a large capital P, three columns deep, a design concept surely meant to draw the reader in visually. “Polly brushed her head against Carlos’s feet, their soles pink and curved in rubber sandals, for these were her refuge from danger, flailing the air and sand on the beach that was damp from ocean and salt…” By the time the sentence ends—four pages, ten characters and several storylines later—I’ve figured out that Polly is a dog and the words mainly concern what is happening inside various minds, being thoughts and situations that have been going on for a while now, time being far from linear. The setting is a voluptuous Gulf island, although sometimes it’s somewhere else. The consciousness of the novel is splintered. I soon get lost, annoyed, stop reading. On the second attempt, I nod off.

Days later, I begin again with diligence and a pencil, underlining key bits of information, constructing a character chart on the inside cover, like the tool provided by Gabriel García Márquez’s publisher for readers approaching the labyrinth of One Hundred Years of Solitude. There are precedents for this kind of literature, reasons to persist. José Saramago’s Blindness, sparse punctuation a dizzying feeling of being blind. Gertrude Stein’s vertiginous thought stream. Ulysses, a single cacophonic day in Dublin telling all Joyce knew about the time and place of his birth. I make a mental note to dip into some of the other modernists whose works I have lugged around since university. Weeks go by. I realize I am not reading Marie-Claire Blais, and so decide to take a journalistic approach and hunt down the woman herself, to pry into the personal hoping for an entry into her daunting prose.

It’s an American story. Eldest of five children born in 1939 to a working-class family in a suburb of Quebec, educated by the nuns until she drops out at fifteen, moves into town, and rents a room, seeking quiet and time to focus on her writing, already an established passion. Feeds a feverish imagination by reading Rimbaud, the Surrealists, Lautréamont, Dostoevsky. Catches the attention of a modern-minded Dominican priest, Père Georges-Henri Lévesque, who is then vice president of the Canada Council. He secures publication of La belle bête and a year-long grant for her to write in Paris. Upon her return, she is discovered by American critic Edmund Wilson during his grand tour of literary Canada (Toronto and Montreal), and hailed as “a true ‘phenomenon’” in his now-legendary tome O Canada, An American’s Notes on Canadian Culture.

A fall day in 1962: Wilson, a critical titan in his late sixties, is visiting Montreal with his fourth wife, Elena. He summons the young author for a drink at the Ritz on Sherbrooke Street West. Living in student digs near McGill, Blais is caught off guard, throws on a baggy sweater, and is mortified to find a dignified couple whose attire perfectly matches the dark blue velvet wallpaper of a very English establishment. Wilson is surprised, too. In his diaries, he mentions that her photos had led him to expect “a big tall rather coarse-featured country girl.” Instead, he is delighted by “an attractive little woman with well-developed breasts but tiny hands and feet, a sharp nose, a very small mouth, and deep-thinking, gray-green eyes.” She has, he adds, “the good, quiet manners and the very pure French that I suppose she learned from the nuns.”

In her memory of the meeting, recorded in American Notebooks, Blais compares Wilson to the “powerful (and avuncular)” Winston Churchill, but reserves her lyrical attention for the “stunningly beautiful” Elena, noting her strong, irregular features; her high cheekbones that seem permanently flushed by cold; her smile, etc., etc.

A huge fan of La belle bête, Wilson had promoted the author for a Guggenheim Fellowship and offered an open invitation to visit his grandiose home in Wellfleet, on Cape Cod, at the time the hub of a lively artistic circle that included poets Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Hardwick, and novelists Mary McCarthy (Wilson’s ex-wife) and Philip Roth. The Ritz encounter, as they say, changed her life. She rented a basement apartment in Cambridge, and during a fiercely lonely first year, surrounded by a language she barely spoke, struggled through what many consider the best of her early novels: Une saison dans la vie d’Emmanuel.

The sixteenth child of an impoverished rural Quebec family, Emmanuel is born on a winter morning, handed over to his grandmother so his mother can return to work that day. A breathless, Dickensian plot, Günter Grass without the war, the story careens in and out of various characters’ heads, presaging Blais’s penchant for multiple points of view. Published in 1965, the novel won the Prix Médicis in France and was translated into thirteen languages. Wilson wrote a laudatory introduction to the American edition. The novel still seems audacious, presenting candid descriptions of adolescent sexuality in religious schools, and a central female character who ends up happily supporting her rural family by working at the village bordello.

With the exception of one extended return to Quebec in the late ’70s and several summer visits, Marie-Claire Blais has spent most of her writing life in the United States and France. Begun as a mind-broadening experience, her American sojourn soon turned personal. Through the Wilsons, she met Mary Meigs, a wealthy New England painter, and her partner, political activist Barbara Deming, both a good twenty years older, who shared a house in Wellfleet. One day, while Meigs and Blais were walking in the woods, a tree branch snapped back and hit Blais in the eye. Blinded and unable to work, she moved in with Meigs, who took care of her. At the time, Deming was in jail in Georgia for her involvement in a civil rights protest. Upon her return, the three lived in a ménage à trois for a while, until Deming withdrew. Meigs and Blais formed an enduring if rocky alliance, the details of which fuelled the novelist, prompting Meigs to write three fascinating volumes of autobiography, politely pointed efforts to set the record straight.

Edmund Wilson’s early book Axel’s Castle had solidified his association with modernism, but his patience with experimentation didn’t last. By the time he met Marie-Claire Blais, he wanted fiction that reflected the times and incited readers to take up arms. He scorned Blais’s experiments, advising her to read Walter de la Mare. Physical love between women, he lectured, was like “a glove made for the left hand worn on the right.” In her diaries, she agonized over whether she could continue to respect a man who did not adore Kafka.

The mentor-acolyte relationship stalled on aesthetic grounds, but it failed elsewhere, too. Wilson harboured a protective passion for Meigs. He was furious when “the little bitch” fell in love with a French author (believed to be Irène Monesi), and convinced Meigs to sell her Cape Cod property and move with them to Brittany. He warned Meigs to nail down her fortune and keep a close eye on the spendthrift Canadian. (Of the three books to result from that drama, Meigs’ memoir, The Medusa Head, is the most interesting.)

Since the ’80s, Marie-Claire Blais has lived in Key West, the geographical if not the spiritual setting of her magnum opus. A social animal who keeps up many friendships in far corners, she dragged her friend Michel Tremblay down for a visit in the early ’90s. He ended up buying a house there, although they travel in different worlds. Tremblay brings friends from Quebec; Blais is ensconced in the local nightlife and arts scene.

The lush coastal landscape of Key West is sensuously evoked in Soifs and the novels that follow. I finally found my way into that symphonic universe, where water metaphors dominate, the prose style an ocean of worlds with many plot tributaries, nothing solid, nowhere to touch bottom. Yet in many ways, the community presented evokes the one first encountered by a high-strung young provincial who was thrust up against the New England intelligentsia of the ’60s. Political activism versus art is the central conflict facing the main characters, some of whom are based on people Blais has identified from her life. Far from Emmanuel’s squalour, theirs is an often-festive occasion teeming with ideas, theories, observations, descriptions—the heady dinner table conversation of erudite, creative people.

On one of her visits to Montreal, Marie-Claire Blais chooses the time and place to meet. It is late afternoon in the grandiose, ultra-trendy Sofitel Hotel bar on Sherbrooke Street West. A tiny woman with thick, dark hair threatening to hide her face, she is perched on the edge of her chair. She has ordered a glass of Chardonnay and will swallow less than an ounce while we talk, her voice so soft I’m sure the tape recorder will be useless, her gaze so intense I’ll be unable to read my scribbled notes.

“Personally, I don’t like suffering. I prefer serenity. I am not at all a dark person; in fact, I love it when friends drag me away from writing and out to a bar, although sometimes I write in bars, too. It’s just that so many of my friends seem to have an aptitude for suffering. You know, Sylvia Plath—really, it could happen to anyone. The world is a terrible place, but we have the tools to change. We have just to wake up. Yes, Obama, but I would really have loved to see Clinton. It’s good to know she’s still there.”

At the end, she writes her phone number in my notebook and insists on paying for the drinks, the first time in my experience as a journalist this has happened. She is, as those who admire her say, generous, friendly, easy to like, and at the same time utterly mysterious, obviously composed. A cheerful emissary for all she has written. I could imagine her cutting loose in a karaoke bar, Robert Charlebois or Lynda Lemay. Yet there is something of the nun in her demeanour, a body filled with otherworldly thoughts.

“Marie-Claire writes from her own need,” says Michel Tremblay. “She writes for herself.” Poet and translator Émile Martel, president of pen Quebec, says it’s true not many people read her, “but they buy her books. That’s half the battle,” he quips. An army of academics and critics has effectively canonized Blais in her lifetime: some eighty theses written on her work, plus a thick bibliography of books and articles; honours, prizes, literary jury duty, frequent appearances and readings. A cult, says Martel. For three consecutive years, PEN Quebec voted to put her name forward when the Swedish committee came asking for their advice on Nobel candidates.

My eighth grade teacher gave our class a brief and highly effective course in speed reading, a series of techniques, how to skim a page, hang on to the beginnings and endings of paragraphs, scan for key phrases, and squeeze meaning out of prose without having to mouth each successive word. This skill proved extremely useful around exam time. Its value has endured into researching magazine articles and reading books for review, but proved a huge liability in the face of the extraordinary literary achievement that is Soifs and the two connected volumes leading to Rébecca, Born in the Maelstrom.

There is only one way to read the latter novels of Marie-Claire Blais. Slowly. One word, one phrase at a time, and then the next. Preferably in a quiet place where there is no phone and no deadline. Ideally, in two or three long stretches, when you can fall asleep and then begin again in the morning, until the absence of punctuation finally becomes an absence of noise. The ends of disconnected threads begin to reappear. Familiar names pop up, voices, like conversations overheard on a journey. Once it all starts to make sense, you feel utterly grateful and deeply connected, in tune with humanity, mesmerized, ready to go on and on. These are truly books of our time, if, maddeningly, perhaps sadly, not for our time.