The Canmore Nordic Centre, 100 kilometres west of Calgary, was the site of the cross-country and biathlon events during the 1988 Calgary Winter Olympics, and it remains the base for both Canadian national teams. It’s also where Beckie Scott is based: she skis there and lives just down the hill with her husband and their two young children. Scott was the first Canadian to earn an Olympic medal in cross-country skiing, winning gold at the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Games—though it took two years of investigations and uncertainty before the two Russians who crossed the line ahead of her were stripped of their medals for doping.

Athletes around the world, competing and retired, have long admired Scott for standing up for fair play, both through her competitive record and her advocacy since retiring from competition. For these reasons, she was appointed to both the foundation board of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the athlete’s commission of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), in 2005 and 2006, and to WADA’s executive committee in 2012. She was also, until 2018, a member of WADA’s Compliance Review Committee, the oversight body that tracks compliance to the agency’s anti-doping code. Scott is a rarity, having succeeded at the highest levels of sport as both a competitor and a policy maker.

But, in many ways, these experiences, which ought to have been purely rewarding, have been compromised by doping and the bodies set up to stop it. “I have seen the dark side of sport,” Scott told me when we spoke at the Nordic Centre in late spring. “The corruption, the allegiances, and the power.” Over the last five years, details have been emerging about the Russian state-sponsored doping system that peaked at the 2014 Sochi Winter Games, where dirty urine was exchanged for clean urine through a “mouse hole” with lab techs on one side of the wall and Russian agents disguised as sewer engineers on the other. These revelations led to the closure of Russia’s national drug-testing laboratory, the suspension of its track federation, and the banning of Russia from the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, where its athletes were forced to compete as “Olympic athletes from Russia.”

Since 2016, Scott has become an increasingly vocal critic of WADA and the IOC as they sought to appease Russia, primarily by watering down the criteria for the country’s reentry into the international sporting community. This criticism did not go over well with the bureaucrats in either organization, and WADA members condemned Scott in ways that she has called bullying and that a recent report commissioned by the organization itself conceded “could be viewed as aggressive, harsh, or disrespectful.”

Scott’s tribulations demonstrate that fault for the crisis polarizing the anti-doping community rests just as much with those who don’t play fair as with those dedicated to upholding fair play—bodies such as WADA, which was created expressly to bring a unified voice to the fight against chemical cheating in sport.

In November 2019,WADA will celebrate the twentieth anniversary of its founding. A lot has happened in the world of anti-doping in those two decades—much of it good. The Athlete Biological Passport, first launched in 2002, is now a central tool for tracking what athletes put in their bodies. Another positive moment occurred when Interpol joined forces with WADA, in 2009, allowing for the criminal investigation of cheaters. But, in an age of escalating mistrust toward traditional touchstones (religion, business, politics), the idea of fair sporting contests holds a simple appeal in our complicated lives, a truth that ought to have cemented WADA’s relevance and credibility.

Instead, opinions about WADA held by a growing contingent of competitors and national anti-doping organizations now range from unease to outright scorn. Why did this happen? Who let it happen? And what does it all mean? At the precise moment we need it most, WADA appears to be abandoning the very people it was founded to defend: clean athletes.

In the summer of 1998, then IOC president Juan Antonio Samaranch was watching the Tour de France in his home in Lausanne, Switzerland. A scandal was unfolding in which Festina—then one of the world’s top cycling squads—was caught with a carload of blood-doping materials, evidence that led to the ultimate finding that the entire team was doping its riders through a supervised and regimented program. The sporting world was aghast, but not Samaranch. “This is ridiculous,” he said to his television. “Anything that doesn’t act against the athlete’s health, for me that’s not doping.” Samaranch, I was told, had become so wrapped up in what he was watching that he’d forgotten a journalist from Spanish newspaper El Mundo was in the room. Samaranch’s comments were picked up around the world: IOC leadership was recommending a permissive approach to performance- enhancing substances. Dick Pound, a Canadian lawyer, IOC doyen, and one-time Olympic swimmer, recounted this story in a phone interview from his Montreal office. “It was,” he says, “a shitstorm.”

Samaranch called a board meeting. The organization had never taken a particularly structured approach to doping in the past and typically handled doping matters by letting either individual countries or individual sporting federations rule on them (as in the case of the Canada-led Dubin Inquiry, which dealt with the furor after sprinter Ben Johnson tested positive for anabolic steroids at the 1988 Seoul Olympics). The best way to save the IOC’s credibility on doping, Pound suggested, was an international, independent organization that could police an aggressive anti-doping policy: those who cheat don’t play. Samaranch gave his blessing and, in February 1999, deputized Pound to gather major players from sport administration, government, athlete groups, coaching, and even the pharmaceutical industry in one room, in Lausanne. After everyone agreed to Pound’s opening suggestion about creating a shared agency across all fields, there was a problem. Governments complained that they were not being given as much power in the proposed organization as sporting bodies were. Pound called a timeout to consult with Samaranch. He then went back and told the governments that he was going to give them what they wanted: 50 percent of the voting rights. Of course, that meant paying half the cost of the new organization. They couldn’t argue. WADA was formally created in November.

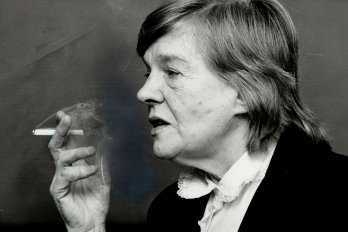

It took nearly four years for WADA to develop what it calls “the code”—the first universal set of anti-doping rules, which outlines violations, testing protocols, analysis methodology, sanctions, appeal processes, and much more. (The agency also publishes a list of prohibited substances and blood-doping methods.) In March 2003, in Copenhagen, Pound chaired the conference to finalize the code, painstakingly leading the same throng of players and parties through it, clause by clause. At the end, Pound told the group that it was decision time. “If you’ve been to these international meetings,” he told me, “quite often, the way voting occurs is that everybody applauds. But I said to myself, ‘No, no fucking way.’ I mean, you’ve got cycling that doesn’t want it, you’ve got soccer that doesn’t want it, and so I said, ‘Is there anybody in this room who does not think we should go ahead with this code?’ I looked cycling in the eyes, looked soccer in the eyes. They all blinked, and I said, ‘Okay, in that case, it’s unanimous!’”

With the world’s only globally agreed-upon anti-doping standards in place, WADA established its head office in Montreal. These were the days of Lance Armstrong (whose seven consecutive Tour de France wins would ultimately be wiped off the record books after his cheating was exposed), Barry Bonds (the baseball home-run king who, due to his doping, still has not been admitted to the Hall of Fame), the Bay Area Laboratory Co-operative (which supplied pharmaceuticals to athletes far and wide), and Marion Jones (the Olympic track-and-field champion who confessed to doping after being caught). WADA was the new sheriff in town, and its presence did away with the patchwork system of poorly enforced and often confusing anti-doping policies, in which different sports had different lists of outlawed substances—a landscape Pound has called “anarchy.”

Governments aligned their domestic policies with the code, thus harmonizing the rules governing anti-doping in all sports and all countries so that every athlete in the world could be held to the same standard. The number of drug tests being carried out increased substantially. As further pressure, WADA made code compliance mandatory for sports in the Olympic program, and the IOC decided to accept Olympic bids only from governments that ratified the code. Pound raised WADA’s profile most noticeably through his spat with Armstrong, in which he publicly stated his belief, long before there was hard evidence, that Armstrong had been doping—a claim Armstrong took considerable objection to, calling Pound “a recidivist violator of ethical standards.” Pound’s reply? “Cheating is cheating.” (Today, Pound says he was “pleased to see Lance had found a thesaurus.”)

All in all, it was a good time for WADA, not least because, in an age when clean sport was under threat from money and drugs, the agency gave the world a reference point for fighting the good fight.

WADA’s next president, John Fahey, was an Australian politician whose tenure, from 2008 to 2013, passed with relatively little controversy and generally positive growth. WADA’s code was gaining respect and recognition. Its budget—half from governments, half from sports bodies—was increasing. Athletes, Scott among them, were becoming more involved. In 2014, Scottish sports diplomat Craig Reedie took over from Fahey. This raised red flags in some quarters because Reedie was a long-time IOC executive committee member (a vice-president, in fact) and did not resign from that position when he took over WADA.

It was about a year after Reedie started the job that a bomb landed on his desk. The German public broadcaster ARD aired a documentary, in December 2014, alleging that Russia was doping its track-and-field athletes and that even Moscow’s main anti-doping laboratory was cooking up ways to beat the system. WADA asked Pound to conduct an independent report on the allegations. Pound delivered his report on November 9, 2015, stating that he found the whistle-blowers credible. WADA then suspended Russia’s Anti- doping Agency (RUSADA), declaring it noncompliant. On the strength of the evidence Pound uncovered, the council of the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), the organization that runs the world’s track-and-field events, effectively banned Russian athletes from its sanctioned events. The ban has remained in place even as recently as the IAAF World Championships in September 2019.

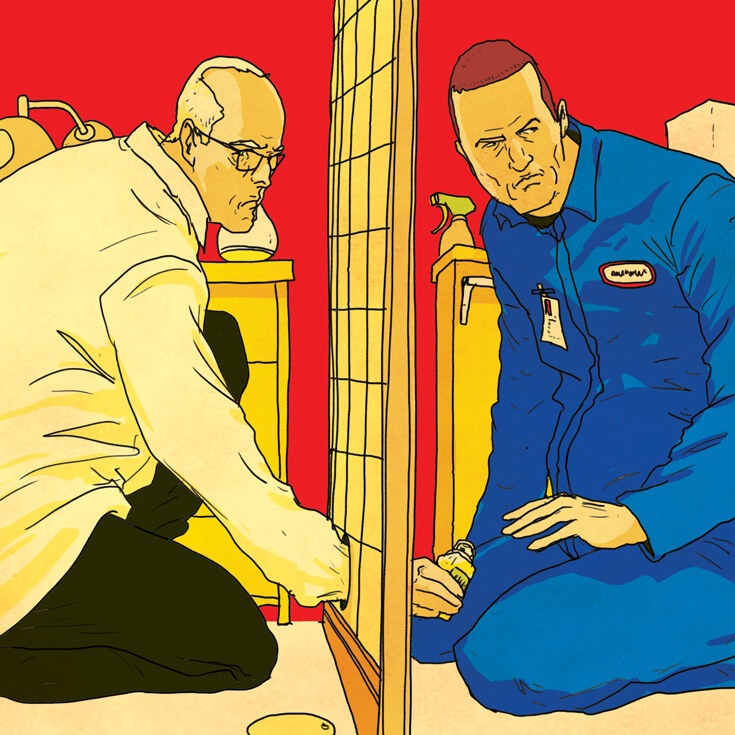

The day after Pound released his report, the head of the Moscow lab, Grigory Rodchenkov, resigned. Matters intensified when Vyacheslav Sinev, chair of RUSADA’s executive board, and Nikita Kamaev, its former executive director, died abruptly and mysteriously in February 2016. Four months later, the New York Times, working with Rodchenkov as a source, published the first of three major articles that deepened the ARD allegations by claiming that Russia had been engaging in doping for years. WADA reacted to these stories—as well as a 60 Minutes interview with Rodchenkov—by engaging Richard McLaren, a respected Canadian sports-law professor, to investigate Rodchenkov’s claims. With the 2016 Rio Olympics fast approaching (meaning Russia’s status as a participant was at stake), McLaren produced a nearly 100-page report in just fifty-seven days. On July 18, 2016, he went to a podium to tell the world what he’d found.

McLaren stated unequivocally that one of the world’s largest sporting powers had been revealed to have cheated regularly, in virtually all Olympic sports, for all athletes, in every major event, through a chain of command that led to the Russian minister of sport, who likely reported directly to Vladimir Putin. The serial cheating included, he said, the extraordinarily brazen urine-swapping caper at the 2014 Sochi Winter Games. It was incontrovertible, concluded McLaren, that “Russian officials knew that Russian athletes competing at Sochi used doping substances.”

WADA, to its credit, did not soft-pedal the findings. Reedie released a statement recommending that the IOC and the International Paralympic Committee decline entries for every Russian athlete at Rio 2016, that all Russian officials be denied access to the Rio Games and other international competitions, that RUSADA continue to be deemed noncompliant, and that the Moscow lab’s accreditation process be halted. Russia’s conduct, Reedie wrote, “shows a total disregard for the international community” and involved a “modus operandi of serious manipulation,” including state oversight. “WADA,” he added, “is calling on the Sports Movement to impose the strongest possible measures to protect clean sport for Rio 2016 and beyond.”

The release of that statement was WADA’s high-water mark of ethical leadership. It also marked the start of the disintegrating relationship between Beckie Scott and the organization she thought stood for fair play above all else.

WADA’s blunt statement and the authority of the McLaren report made it seem that the IOC’s only credible move would be to ban Russia from Rio 2016. What happened next was the turning point in WADA’s arc.

After WADA called for Russia to be banned, IOC president Thomas Bach turned black into white and blamed WADA for not doing its job properly. At an IOC session, just before the Rio Games, Bach trampled all over the agency. “Recent developments have shown that we need a full review of the WADA anti-doping system,” Bach said. “The IOC is calling for a more robust and efficient anti-doping system. This requires clear responsibilities, more transparency, more independence, and better worldwide harmonization.” He said the “nuclear option” of banning Russia was unacceptable and added that the result of such a move would be “death and devastation.” Other IOC board and committee members accused WADA of sullying its own reputation and of attacking the “Olympic family.”

Astonished journalists’ reports went out around the world. The Times of London called Bach’s attack “cowardly.” The German paper Bild ran a photo of Bach and Putin with the caption, “Putin’s Poodle.” “Far more damaging for Bach and the IOC’s reputation,” reported Olympic-news website Inside the Games, were “the jubilant reactions in Russia” after it escaped banishment from the Rio Games.

In the weeks following the IOC’s decision, Reedie was quoted by multiple outlets expressing his disappointment. During the fray, there was perhaps a moment for him to challenge the IOC and push harder for the ban, but he remained silent, a signal to many that he was serving the IOC first and WADA second. Reedie remained on the IOC executive and was elected to another term as WADA president later that year. In response to the question of why he didn’t resign from his role with the IOC when he took over WADA, a spokesperson from WADA pointed out to me that Reedie’s situation was analogous to that of Pound, who held executive positions with both organizations when he founded the agency.

“We predicted it back in May of 2013,” Travis Tygart told me in a phone interview. Tygart is head of the US Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) and the man who brought down Lance Armstrong. The “it” he referred to was the tension that emerged from Reedie’s appointment as WADA president. “We said then that WADA would drive all their good work in the past right off a cliff.” And today, said Tygart, we can see the results. “Athletes have lost confidence in WADA, and WADA has been shaken to the core because of its conflicted governance, which reacted very suspiciously to the largest-scale state-sponsored doping the world has ever seen. WADA has unfortunately become just a lapdog of the IOC.”

“The big question,” Pound said to me, “is how could somebody who does care about sport, faced with the evidence of what the Russians were doing, not respond with a much more severe sanction?” If the IOC had truly wanted to bring about what Pound calls “conduct change” (meaning an end to doping), banning Russia from Rio would certainly have achieved it. “By the way,” he added, “one person you should talk to about all this is Beckie Scott.”

After the debacle of the Rio Olympics and Paralympics—during which the IOC banned no Russian athletes, but the IAAF and the International Paralympic Committee banned all Russian athletes—Beckie Scott found herself sitting in various WADA boardrooms, along with the rest of the Compliance Review Committee (CRC), trying to figure out how to square the circle of Russian cheating and IOC equivocation.

By the fall of 2017, RUSADA, Russia’s anti-doping agency, remained suspended, preventing the country from competing in international competitions and from hosting major sporting events. It was clear, to Scott and others on the CRC, that the IOC was pressuring WADA’s executive to find a way out of the crisis, in what Scott had called the “save Russia” movement. There are differing opinions as to why. They range from Bach’s close friendship with Putin to allegations that some IOC members wanted to avoid endangering business interests in Russia to the reality that Russia is one of the few remaining countries likely to keep bidding on future Olympics. Whatever it was, it put WADA at odds with the IOC.

Many inside the organization continued to advocate for a continued suspension of RUSADA, but others with stronger IOC connections advocated for lesser punishment. Ultimately, the CRC, with Scott’s support, put forward a Roadmap to Compliance Russia would have to follow in order to regain accreditation for its anti-doping authority. Among these criteria was that Russian authorities had to give WADA access to the urine samples from the Moscow lab tied to the Sochi cheating. Russia also had to accept, in full, the McLaren report.

To no one’s surprise, Russian authorities strongly objected to the way McLaren’s report linked the doping crimes to the Russian state apparatus. So the IOC commissioned its own report. Samuel Schmid, a Swiss member of the IOC ethics commission, delivered his version of events to the IOC executive on December 2, 2017. It was a virtual retelling of McLaren’s findings of rampant Russian cheating. There was, however, one crucial difference—the only difference that counted. Where McLaren’s report had labelled the Russian doping program “state-sponsored,” Schmid concluded that he could not find any evidence “confirming the support or the knowledge of this system by the highest State authority.” In other words, don’t blame Putin.

Because it did not contradict McLaren’s primary findings, Schmid’s report made it impossible for the IOC to avoid levelling sanctions against Russia without losing face. On December 5, 2017, it banned the country from the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics. But it was only later we would learn that in the months that followed the Pyeongchang games, WADA negotiated with Russia to substitute the Schmid report for the McLaren report in its Roadmap criteria, effectively appeasing Russia’s dislike of McLaren’s implications.

When I spoke with WADA director general Olivier Niggli about it, he told me that the Schmid report’s use of the term “institutionalized doping” instead of “state doping” was significant for Russia. “One actually means that the head of the country would be involved, as opposed to, yes, there was some part of the administration that might have been involved.” RUSADA and the Russian Ministry of Sport were therefore more prepared to accept the Schmid report.

The full implications of that substitution wouldn’t become evident until September 20, 2018, at a meeting in Seychelles, when WADA debated reinstating RUSADA. The problem was that Russia had now accepted the Schmid report but had yet to meet the other important criterion laid out in the Roadmap: access to the lab. According to the minutes of that meeting, Beckie Scott said that she had heard from athletes around the world and that they had spoken, almost as if with one voice: deny Russia reinstatement. “I urge you to make a decision based on who your constituents are, who you are serving and who you are accountable to,” she said, “because I do believe this is a defining moment for WADA.”

Her message was ignored. The meeting became even more heated when Scott expressed frustration at how the WADA Athlete Committee, created to champion clean athletes, was under constant scrutiny from the IOC, which, at every turn, seemed to impede the committee’s aims. Some members called her integrity into question, suggesting she was grandstanding for her own issues. Her attitude was called “victimistic,” and she was told that athletes, while playing an important role, needed to know “their place.” Ultimately, the CRC disregarded her counsel—according to Scott she was actually laughed at—and recommended reinstatement for RUSADA on the condition that Russia allow WADA access to the Moscow lab by the end of 2018. The executive swiftly ratified it. WADA released a statement later that day announcing the decision, though its executive likely sensed how the reinstatement would be received. In the press release, Reedie wrote, “WADA understands that this decision will not please everybody.”

Everybody? How about nobody.

The worldwide response was scathing, immediate, and contemptuous. “WADA’s move to reinstate Russia’s anti-doping body is a farce,” wrote the Economist. If this is WADA’s response, ran a headline in the National Post, “Why Would Russia Hesitate about Cheating All Over Again?” Thirteen of the world’s most respected national anti-doping organizations—those of Australia, Austria, Canada, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, the UK, and the US—released a joint statement expressing shock that “WADA’s leading compliance body is recommending the reinstatement of a country that perpetrated the worst doping system ever seen in international sport.” Even WADA vice-president Linda Helleland said, “We failed the clean athletes of the world.” Beckie Scott released a statement saying that she was “profoundly disappointed” and that WADA had “dealt a devastating blow to clean sport.”

Just over two weeks later, on October 8, 2018, Scott sent a letter to Reedie and Niggli in which she outlined the “derisive and inappropriate” treatment she’d been subjected to at the Seychelles meeting. WADA responded with a perfunctory internal investigation, which Scott deemed invalid.

The agency now found itself pitted against the personification of what it had been created to defend. Scott pursued her athletic and policy career with such an exemplary record that she had come to symbolize everything clean sport was about: clear rules, tough questions, and transparency around punishing cheaters. WADA not only emptied these things of meaning—it also made her the antagonist. It hired an international legal firm, Covington, to conduct a second investigation. Scott and USADA chair Edwin Moses, who had also filed a harassment complaint against WADA, made it clear that they would not participate in the investigation due to a perceived conflict of interest: Covington had previously advised WADA on legal issues, specifically privacy and data protection. WADA dismissed these concerns. Covington claimed that it was never presented with evidence of a conflict and forged ahead with its investigation.

Meanwhile, WADA continued to draw savage criticism over its handling of the Russia affair. When Russia missed the Roadmap deadline to allow WADA investigators access to its lab, WADA gave Russia more time. The international community was again outraged. “It’s time for WADA to stop being played by the Russians and immediately declare them non-compliant,” said Tygart in a statement.

That did not happen. It wasn’t until January 17, 2019, that WADA announced they had “successfully retrieved” data from the lab. This was followed by another announcement, five months later, that WADA had gathered a further 2,262 samples. In simpler times, these actions would have been celebrated by clean athletes and their advocates around the globe. But skepticism toward WADA was so high that many questioned the value of the exercise simply because WADA was running it. When, in late September 2019, the agency announced that data from the lab samples appeared to have been tampered with—these being the very samples Russia had agreed to turn over in exchange for being reinstated—that skepticism was seen as warranted.

I met with Scott in Canmore, in early May, just as Covington was wrapping up its investigation. I asked her why any of it even mattered, why clean athletes deserved protection in an era when sport is so often equated with vast professional contracts, televised entertainment, and corrupt governance. “It matters,” she said, “because sport is one of the few things left in our world that holds the power for good. It really does transcend barriers. It really does unite. It really tells stories of human spirit.” And sure, she added, “you could just make the whole thing a contest to see who has the best pharmacist, but that doesn’t reflect what society in general ought to aspire to. We can say, ‘Let it be a free-for-all,’ but often the athletes are trapped, they’re manipulated, they’re used, like with the Russian situation. We have a moral obligation to look out for vulnerable people at a vulnerable time in their life, who are often young and easily influenced and may not always make the right decision or have perfect judgment.”

A week after Scott and I spoke at the Nordic Centre, the Covington report was made public. It exonerated WADA and the IOC, declaring Scott’s claims of “unprofessional behaviour” directed toward her unfounded. A few days later, an analysis of the report by the Sports Integrity Initiative, an independent online publication, concluded that “pressure was undoubtedly put on Scott by members of the Olympic Movement,” which was unhappy with the WADA athlete committee’s stance. The Initiative continued: “WADA has shown its true colours. It prioritises politics and the views of the IOC over the views of athletes.”

The IOC, for its part, will hear none of it. I spoke by phone with the IOC’s director general, Christophe de Kepper, in early May. I asked him how the IOC responded to the notion that WADA suffers from too much IOC interference, especially around the Russia affair. “I think it’s an unfair criticism,” he said. “The IOC has nothing to do with the Russian affair. It’s absolutely pointless to try to point fingers at some of the entities.”

If that was the case, then why were so many critical of the IOC? “You have to ask them,” he said. “It’s actually not very constructive, putting into doubt WADA’s governance by accusing some of its stakeholders and principally the IOC.”

The day after the release of the Covington report, I emailed Scott, and she told me that parts of the report “were complete fiction, and parts designed to portray me as the perpetrator” and that the entire affair was “brutal and utterly demoralizing.” She continued: “I don’t think I could have imagined that level of viciousness from them.”

Rob Koehler is the former deputy director general of WADA. After resigning, in August 2018, partly in protest over WADA’s handling of the Russia affair, Koehler founded an advocacy group, called Global Athlete, designed to give athletes a stronger voice in the fight against doping. WADA’s actions on the Scott file, Koehler told me, were “more shameful” than its Russia decision.

Outside the IOC palace, WADA’s many critics and even its allies remain divided about its future and utility. “People forget,” said Niggli, “that, without WADA, there would have been no Russian scandal, in that we paid for the investigations to take place, Pound’s and McLaren’s. We published them. We’ve been totally transparent.” McLaren, whose rigorous investigation advanced the Russia crisis into the realm of indisputable fact, reminded me that we should never forget that the formation of WADA was a tremendous achievement. “And it happened so quickly,” he said. “For it go from 1999 to 2004 and be fully operational is incredible. And its original goal of having a harmonized system to make sport cleaner and fairer remains laudable. Still, it needs a vigorous rethink.”

The man who started WADA also appears to have a sense of what’s needed. “Structurally, WADA is pretty well everything that we hoped it would be when we were putting it together,” said Pound. “But it’s hampered by weak leadership.” Tygart would not disagree but believes that, if WADA folds, “at least we’ll know what not to do next time around.”

The world needs WADA, or at least what WADA purports to stand for. Even its fiercest critics don’t dispute that. But many of those same people are wondering if WADA can be saved and whose hands would be clean enough to save it. Perhaps the only group that can now be trusted to overhaul WADA is the very group that WADA is struggling to protect—clean athletes. Which also happens to be the group the IOC takes for granted. Pound was quoted, in 2018, saying that the only thing that “scares IOC old farts” is the athletes themselves.

Koehler told me that some athletes’ unions are in early discussions to set up strike funds so that, should clean athletes decide no one is going to protect their rights and livelihood except themselves, they will have a financial cushion when they refuse to compete. Athleten Deutschland, for example, is a powerful new collective of German athletes formed as a result of the ongoing Russia debacle. Shortly after its creation, in 2017, Athleten Deutschland released a statement entitled, “Anti-Doping and Governance: Time for Athletes to Take Destiny into their Own Hands.” It outlined the athletes’ disappointment with the IOC and suggested that, if the IOC and WADA couldn’t get their acts together, perhaps it was time for those organizations to disband. They closed by saying, “We want no decision without the athlete!” And then, for their work and inspiration, they added thank-yous to Richard McLaren and Beckie Scott.

Scott’s term with WADA, which she vowed to see out, ends in January 2020. I asked her, in Canmore, if she could imagine one day returning to an official role in the world of sports policy and administration. She laughed ruefully. “I’m not naive about what exists out there and where sport may go eventually. It’s just difficult to see how real change will happen. Sport at its most fundamental should be a contest of best efforts with standards that should be universal. There should be rules everybody has to play by.” She paused and looked out the window, the hills full of mountain bikers enjoying the simple pleasure of athletic activity. “But I think, inherently, we know that’s not the case.”

November 13th, 2019: An earlier version of this story stated that Rob Koehler is an Olympic gold medallist. In fact, he is not. The Walrus regrets the error.