The other night, I found myself hotboxing a bathroom with my high-school friends. Looking through the haze at greasy-haired teenagers in dirty socks, I suddenly realized something was askew: I’m not in high school. I’m a grown-up with a daughter. Then, something else hit me—I wasn’t wearing my mask. I searched fruitlessly, choking on the fear that I’d been puff-puff-passing with several chapped-lipped youths. The panic was visceral; I felt physically ill. That sentiment remained even after I woke up and realized that it had all been a dream.

According to Deirdre Barrett, assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and author of Pandemic Dreams, I’m not alone with my nighttime scaries. In fact, our collective nocturnal journeys are now steeped in our daily anxieties and insecurities about COVID-19, and maskless dreams like the one I experienced have recently become the most common theme. “The ‘Oops, I don’t have my mask on’ dream has replaced the ‘Oops, I’m out in public and I’m naked’ dream,” Barrett explains.

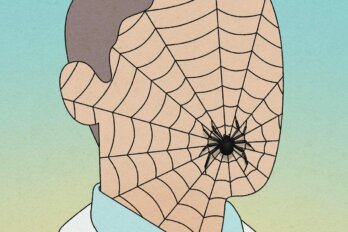

Barrett has been tracking the dreams of over 3,700 English-speaking adults, mostly from North America, France, and Italy, via an online study that began in March 2020. Early on, she tells me, our dream themes were straightforward: visions about getting COVID-19 and not being able to access medical treatment were frequent. So, too, were more symbolic, Hitchcockian scenes that saw the invisible illness morph into terrifying bug attacks. From swarms of bees to black gnats, armies of cockroaches to masses of wriggling worms, bugs were everywhere. “I think it’s partly that dreams look for a visual image, because ‘getting a bug’ means we’re coming down with a virus,” Barrett says. “But also, a swarm of insects being lots of little things that could harm or kill you is a very good metaphor for the virus particles.” Little by little, our minds warped our experiences with waking life, turning our dreams into funhouse-mirror versions of our anxieties.

One need only look at social media for evidence of our nightly terrors. The Twitter account @CovidDreams auto-retweets pandemic dream stories posted by thousands of strangers around the globe united in one shared experience: our unconscious minds are messing with us. As for why our dreams are extra bizarre lately, it’s not exactly the pandemic that’s to blame but our processing of it. “It really has to do with the internal experience of this whole situation,” says McGill psychiatry postdoctoral fellow Elizaveta Solomonova, who has been surveying pandemic dreams in two different studies since April 2020. “We found that, the more people are concerned about the pandemic, the more they report having nightmares and pandemic-themed dreams.” As we trudge through the third wave and vaccination rates continue to increase, will we finally be able to get a good night’s sleep?

When lockdowns and sheltering in place started in North America, Barrett noticed a pattern: those living alone reported extreme dreams about being cut off from the world. People went to bed and found themselves in prison, thrown in solitary confinement. They were sent to space and abandoned on another planet. On the flip side, people locked down in close proximity with families or roommates were attacked by crowding and claustrophobia. “There were multiple dreams where the whole neighbourhood has moved into [the dreamer’s] house,” Barrett explains. “One woman couldn’t walk through her house because there were so many cots set up, and another one was trying to use her toilet and she couldn’t close the bathroom door because everyone’s stuff was jammed in the doorway.” These people were likely experiencing “aloneliness,” where they craved, but could not get, time to themselves.

For many of us, the world has changed more in the past year than at any other time in our lives. Multiple lockdowns, physical distancing, and isolation have all created a strange new reality. Even those of us lucky enough to stay physically healthy have been affected mentally. Way back at the beginning, when Italy was in the midst of its first lockdown, researchers there analyzed the dreams of people confined and found that they were experiencing nightmares and parasomnias common in those with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Not only have our dreams become more delphic but we’re also waking up to tell the tales. An ongoing study from Lyon Neuroscience Research Centre reports that people are recalling their dreams 35 percent more, and memories of them are at least 15 percent more negative than in prepandemic times. There are different theories as to why this is the case. One explanation is that being home affords people a bounty of time to sleep, and increased REM sleep means more dreams. I wouldn’t know—I wake up at least once a night to settle my toddler, who’s also an early riser. When I do remember my dreams, though, they’re almost always laced with dread. As it turns out, my all-over-the-place sleep patterns may be to blame.

“There are basically three patterns in which sleep changed during lockdown,” Solomonova says. People are either spending more time sleeping, spending less time sleeping, or delaying bedtime—meaning going to bed later and waking up later than before. “The ‘extended time in bed’ people are doing the best, but the other two modifications are associated with mental health problems,” she says.

I’m in the less-time-sleeping camp, and not just because my kid wakes up. My days are full of child care, work, laundry, and cooking. By the time my daughter goes to sleep, I know I should soon do the same, but I also want to make the most of my night by reading, watching shows, and scrolling aimlessly through social media. Naturally, there’s a name for my behaviour: it’s “revenge bedtime procrastination,” a phenomenon where people stay up later than they want to, sacrificing sleep to indulge in the free time that they missed out on during the day. But you can’t get revenge on a day gone by, so, sadly, I’m only getting revenge on myself.

As for why my daughter is waking up at night, her own pandemic dreams could be at fault. Even in normal times, children tend to have and remember more dreams and nightmares than adults do. The pandemic seems to have only enhanced this disparity. Since children may be feeling pandemic anxiety acutely, their dreams could become vivid representations of their intense emotions.

Our dreams can also reflect our deepest fears. As Solomonova says, “Whatever we’re afraid of or avoiding in our waking life is probably going to make a vicious comeback in our dreams.” Many of Barrett’s respondents reported dreams about home-schooling—but these didn’t come from students. “Those were all from mothers,” she says. “Absolutely all.” One woman dreamed about failing her son’s math class; another received a message from her ten-year-old’s school that the entire class was being sent to her house—she would have to home-school them all for the rest of the pandemic.

It’s no surprise that mothers are having nightmares about home-schooling. Women—marginalized women most severely—have borne the brunt of the pandemic’s aftershocks, becoming mentally, physically, and emotionally run-down in our roles as caretakers, partners, teachers, and workers. Many of us have been forced to leave the workforce altogether due to insecure employment, layoffs, or to accommodate the demands of our new realities. The United Nations Population Fund also reports that, during lockdown, women are at greater risk of domestic violence.

The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, in Toronto, has been conducting an ongoing national survey that tracks pandemic mental health and substance use. It has found that the mental health gender gap, forged early in the pandemic, has been reinforced, and women report higher levels of anxiety and loneliness. Parents with children under eighteen are also feeling more depressed than those without.

Unsurprisingly, Barrett has found similar results: women have suffered a greater increase in depression and anxiety compared to men, and their anger and sadness is showing up more at night. Solomonova agrees that women have typically experienced more anxiety-based dreams and nightmares. “Dreams extract meanings from new lived experiences,” she says. In other words, our sleeping minds could be attempting to parse the exhausting situations we now find ourselves in, especially if our waking minds don’t have time or space to engage.

Sigmund Freud once called dreams “the ‘royal road’ to the unconscious.” Perhaps this pertains not just to the individual but to the collective as well. Both Barrett’s and Solomonova’s surveys have confirmed that our sleeping lives reflect the societal inequities that existed long before the pandemic arrived. “A consistent finding across our studies is that people who were already not doing well are doing worse,” says Solomonova.

While most of us are more prone to scarier, odder dreams right now, hospital workers who have seen and treated COVID-19 patients have suffered the most. Barrett found that front line health care workers all experienced similar types of nightmares when case numbers were surging in their area. “When I first put the survey up,” she says, “I immediately got some Italian health care providers who were having what’s become the classic PTSD dream from health care workers. It was always some version of: there’s a patient dying of COVID and it’s my responsibility to save their life and I’m failing.”

Barrett tells me that, around April 2020, it looked like many New York City health care workers were having this kind of nightmare, and the same thing occurred several months later in Los Angeles. “It’s the normal course after a trauma that about 50 percent of these people will see those dreams diminish in frequency and intensity and pretty much disappear,” she says. But there are always people for whom those dreams don’t diminish. For them or anyone else having frequent, persistent nightmares about a situation for months or years after it ends, Barrett says she would “emphatically tell them to go to therapy.”

Relentless nightmares are rare, however, and most of us won’t require therapy to help our oneiric states. But anyone experiencing unwanted bad dreams may want to consider dream incubation, which both Barrett and Solomonova recommend as a way to disarm the negative at night. Solomonova describes dream incubation as “a process of setting an intention to dream about a specific theme.” It’s a technique that’s been around for thousands of years: ancient Greeks and Romans used to bring sick people to temples and have them pray to Asclepius, god of medicine, healing, and prophecy, in the hope that he would send them inspired dreams to inform their recoveries.

For us moderns, Barrett’s advice is simple. “Think about what you want to dream and pick out something that would be as happy, peaceful, and calming as possible.” You can be specific by setting an intention to dream about a certain person or memory, or you can take a broader approach, aiming to dream about a general place or theme. According to Barrett, people can even attempt to solve their waking problems by asking questions for their resting minds to answer. “It can be a more serious, involved question, like, ‘I want to have a dream that shows me a way to stop having these repetitive arguments with my spouse,’” she says. “You form the image of what you want to dream on, in your mind, and focus on it until you drift off.” She suggests putting photos or objects that represent your dream goals on your nightstand to look at before falling asleep.

As for where our dreams will go from here, Barrett is optimistic that, with more people getting vaccinated and the news and case numbers beginning to reflect hope in this part of the world instead of dismay, most of our dreams will soon become more optimistic. “Earlier in the pandemic, when someone would dream about happy times out with friends, they would very often remark that they woke up with the terrible realization that this isn’t going to happen in the foreseeable future,” she says. “That changed in early December, when everybody started having happier back-to-normal dreams. They would wake up and say that the dream cheered them up because it’s a depiction of things they’ll get to do fairly soon.”

That’s not to say we won’t have the odd anxiety-tinged COVID-19 dream as the pandemic winds down in the coming months. According to Barrett, these could soon turn into a more common variety of overnight experience—a past-tense mind mix-up, like the one where an adult sits down to write a high-school math test they forgot to study for. It might send you back to a stressful place, but it’s often easily forgotten upon waking. Once life as we used to know it resumes, if we do experience moments of maskless horror, solitary confinement, or a house full of needy strangers, we can wake up with a sigh of relief: after all, it was only a dream.