For 100 years, the Cut Knife Courier was the newspaper of record in Cut Knife, Saskatchewan. Every week, it reported on community news: 4-H club agricultural competitions, the RCMP police blotter, or notable events (the prime minister’s 2019 visit made the front page). When I visited Cut Knife in 2018, after my father retired there, I felt that I already knew it through my email subscription to the Courier.

A forty-five-minute drive west of the Battlefords, Cut Knife is a town of 600 where many of the larger issues Canada faces seem magnified: retired farmers, commuters from the Alberta oil patch, and newcomers from a range of countries share space with as many as five churches and the residents of three reserves. Cut Knife is politically and demographically divided, and it’s trying hard to work on its problems in the midst of economic uncertainty and cultural change. Perhaps because of this, the Courier’s most popular feature was a column written by a cat named Tuc. (“That cat,” my father once remarked, “is able to say things about politics and religion that people couldn’t.”)

When the paper folded, in September 2020, it wasn’t a surprise to anyone, but it was a blow. The Courier had often been lauded as a throwback—a community newspaper still alive in the age of media contraction. Ray and Andrea Stewart, both former horse racers and trainers from Alberta, had bought the paper in 2016. According to Ray, the Courier never made any money. Instead, it had always covered its expenses through a modest grant, over 600 print and email subscriptions, and advertising. But a 60 percent rise in printing costs, coupled with a drop in community advertising, brought it to a close. “When things got to a point where it was going to start costing us money,” he says, “we said, ‘No. It’s time.’”

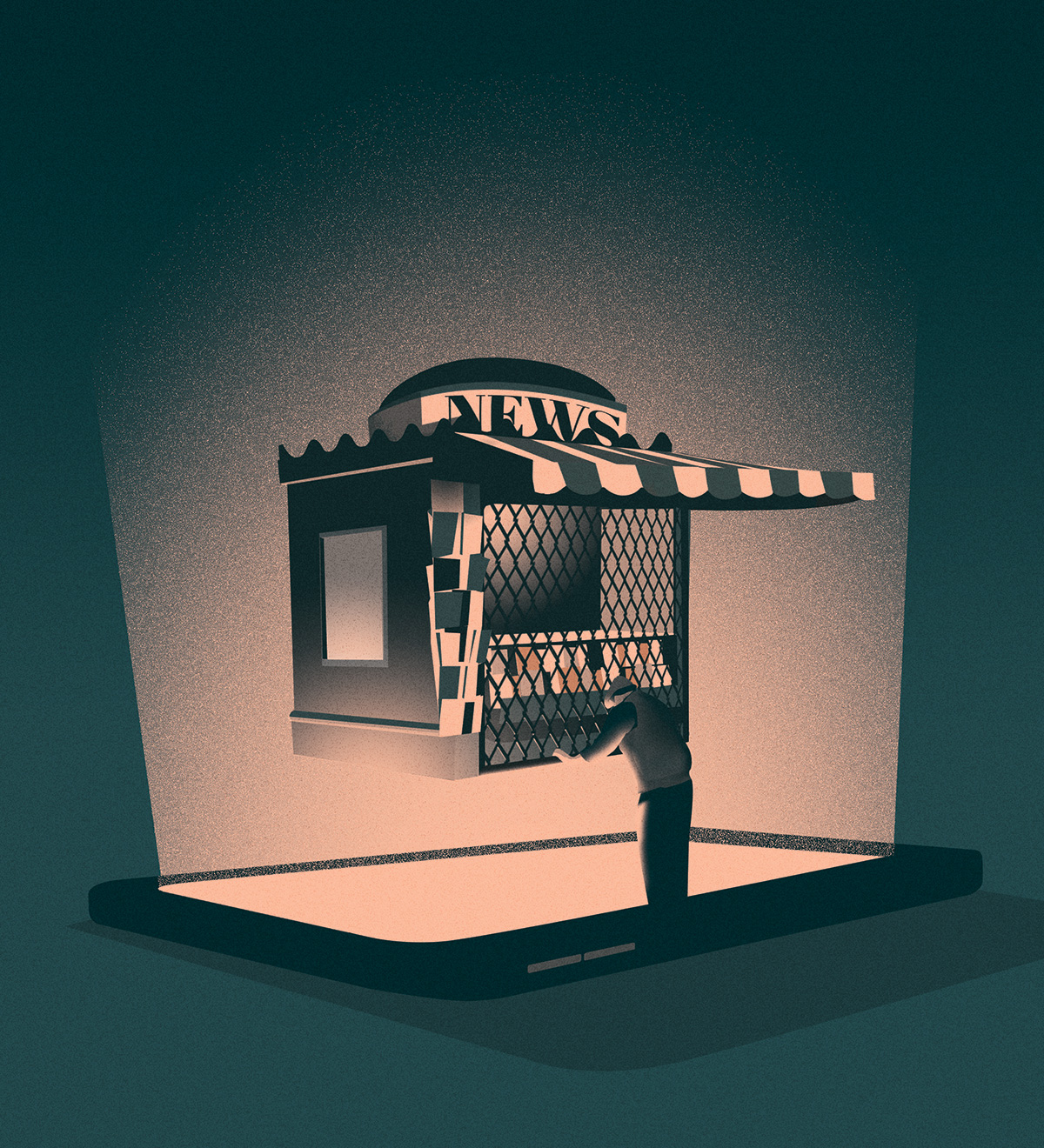

What happened to the Courier is an acutely local example of what has happened in communities across Canada, exacerbated by COVID-19. According to 2020 research, nearly fifty newspapers and upward of 2,000 journalism jobs were lost in the first six weeks of the pandemic alone. Daniel Bernhard, then executive director of the media advocacy group Friends of Canadian Broadcasting, referred to COVID-19 as the media’s “mass extinction” event. As a declining number of people get their news from a traditional print newspaper, one could argue it was a change whose time had come. Here’s a more existential question: What’s going to replace the Courier? It would be great to point to a hot new digital outlet started by North Battleford millennials. It’s more likely that Cut Knife will join the growing number of Canadian communities without any local news coverage. The town’s only media presence is now its new Facebook page.

The Stewarts say there’s no question that the community would have been better served throughout the pandemic if the Courier or something like it were publishing. “Tuc could have said, ‘Go and get your vaccination,’” says Andrea. Many of this town’s older residents don’t use social media, which is where information about vaccine appointments has often been shared. Others continue to doubt the safety and efficacy of vaccination. My father posted a selfie of himself getting a Pfizer shot on Facebook. “I hope this can show other people it might be OK,” he explained. That’s what now counts as journalism if you live in an area without local media coverage.

Platforms like Google and Facebook have transformed the way we consume and share news, but the digital revolution hasn’t yet revealed an equivalent breakthrough in the way the media makes money. This is a paradoxical reality at a time of unprecedented innovation. What about podcasts and digital start-ups and TikTok? What about the reader-funded membership models favoured by independent media websites? Aren’t subscription-based newsletter platforms like Substack the next big thing?

Articles, panels, and think tank reports on the media’s demise abound—along with accusations that the media is too rich, too old, and lacking diversity. In an effort to move beyond the grim headlines, I contacted the heads of influential outlets to ask what is succeeding. What do they know that everyone’s overlooking? “It’s time to stop mourning what’s been lost,” I wrote to them. “What could—and should—the industry look like in the next five to ten years?” I hoped to put together a “good news” report about the industry’s future. What I heard back was sobering.

Friends with jobs in “functioning” industries, like law and real estate, often ask me why my business is so screwed. Here’s what I usually say: the 2008/09 subprime mortgage crash and subsequent recession led to a diminished demand for consumer goods, taking down with it the advertising industry on which many of this country’s best-known media brands, including CTV, Global, and Postmedia, were built. A former women’s magazine editor recalls, “One month, we had a normal book size—20 or 130 pages. The next month, our book size was down to eighty pages. The advertising just dropped overnight.”

Around this time, social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter encouraged users to share links to articles and videos. News went online, usually without paywalls. The same tech companies also started to scoop up digital advertising revenue with powerful algorithms. Today, we take the stickiness of targeted advertising for granted (even if it’s a little uncanny: search for men’s underpants once and underpants ads will dog you on the web forever). But the ability to track our data is of serious value to advertisers. In Canada, Facebook and Google now receive more than 80 percent of all online advertising.

The media is also partly to blame. It lost faith in journalism and tried to compete with an internet awash in cat videos, listicles, and misinformation. Threatened by social media’s ability to glue younger people to their phones as well as competition from online publications like Vice and BuzzFeed, traditional publishers began to post content online without charging for it. (The rationale circa 2012 was: don’t get left behind; bloggers are stealing your audience and can create content faster than you.) The revenue growth print publishers had been promised never materialized. Digital ads—the kind you see as website banners—garner mere pennies even if thousands of people see them. It’s no surprise that many high-profile outlets, like CTV News and the Toronto Star, have struggled financially. (The CBC, the country’s largest media outlet, is effectively publicly funded, and a handful of privately owned outlets, like the Globe and Mail, don’t report their performance publicly.) A small number of independent journalistic nonprofits break even, including The Walrus thanks in great part to our donors. I suspect that a larger number of outlets are hovering around the margins of sustainability, like a failing restaurant whose owners keep throwing money at it, hoping it will turn around one day. After all, everyone thinks the food is great.

Talk to Facebook and Google and they’ll tell you that all they did was build a better advertising model. Why reach only the number of viewers or readers defined by a traditional media outlet’s audience when you can run ads targeted to each person on the internet? Digital ads reach more-relevant customers, and they reach many more of them. Even if the top four platforms were forced to redirect their digital ad revenue back to traditional media, their advertising clients would likely resist.

The handful of print outlets that have managed to turn a profit through online subscriptions and other revenue—like the New York Times, The New Yorker, and the Washington Post—shows that, if you build a product that people value enough, you don’t necessarily need advertising to survive; digital customers will follow. The problem for most media outlets in this country and elsewhere is that they aren’t the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal—brands that draw big, international audiences, the Veuve Clicquots and Audis of news gathering. I’m aware of no comparable success stories in Canada. (While it’s unlikely to get many readers outside of Quebec, Le Devoir was unique in charging online readers early in the game, and it has maintained stability through a mix of subscriptions, donations, and traditional ad revenue.) According to the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, only 13 percent of Canadians pay for online news in the form of subscriptions or paywalls, and more than a quarter of those paying subscribers support international publications.

It’s possible to argue that the industry is not necessarily failing but is instead in market correction as old businesses that can’t evolve, like television networks and newspapers, die out. Dwayne Winseck, a professor at Carleton University’s school of journalism and communication, thinks we overlook the effect of market concentration: through a series of mergers and acquisitions, Canada has ended up with mega-outlets instead of the hundreds of independently owned local, regional, and national outlets that used to make up the country’s media landscape. “CanWest utterly destroyed what had been the Southam newspaper chain. They completely gutted it,” he says, referring to the 2001 takeover of Conrad Black’s money-losing Canadian media empire. The business sections of the 2000s were filled with reports of printing companies (Quebecor) buying up the chains they used to distribute (Sun Media) or newspapers (the Globe and Mail) joining forces with networks (Bell Globemedia). When one of these big companies sinks, it drags an ecosystem of little players down with it.

“The decimation of journalism unfolded over a quarter century, and nobody did boo,” says Winseck. “Instead of looking in the mirror and at their own complicity, the media is pointing fingers at Google and Facebook. And that’s just crazy.” Legacy media companies, in other words, have become the carriage maker who, after the invention of the automobile, stands around crying, “But we made very good carriages!” The industry’s failure to make money is the industry’s failure. The media, after all, is a business, and it has been since newsies tried to outsell one another by shouting out their papers’ headlines to passersby. No one owes us an audience, paying or otherwise.

But, if the media is a business, then a more fruitful way to assess it might be to look at it through the lens of the market in which it operates. Right now, the industry exists in a limbo where many of the old models are dying before the new ones have become profitable. It’s not clear whose responsibility it should be to save these institutions. The government? The platforms that undermined them in the first place? Or the consumers who have never fully paid for content but who stand to lose the most if the media goes away?

In recent years, governments of different countries, including Canada, have looked at regulating Big Tech platforms in an effort to shore up ailing media industries. These platforms, specifically those that use the work of creators to drive their algorithms, are sometimes collectively referred to as GAFA (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple). There are many elements to the proposed regulation. While efforts to address disinformation and online hate have received a lot of attention—ideas that recirculated in the wake of the documents whistleblower Frances Haugen released, dubbed the Facebook Papers—the aspect of this discussion most directly related to the media’s financial survival is revenue. In 2021, Australia passed legislation that would require GAFAs to compensate media outlets when users post links to their content—the social media equivalent, perhaps, of paying someone to reprint an article under copyright law.

Similar legislation was included in the Liberal government’s recent election platform, to be completed in its first 100 days. Over the summer, the office of the minister of Canadian heritage solicited input from forty-six stakeholders on how the regulation of GAFAs might affect their businesses and which platforms and media organizations should qualify for the regime. It also sought opinions on two different models for what form said regulation could take: individual arrangements, brokered by the government, to be negotiated on a per-outlet, per-platform basis; or a standardized contribution from every platform, to be allocated to an independent pool and dispensed to outlets in a manner yet to be determined.

The difficulty of trying to align the needs of organizations and platforms as varied as Bell Media, the Globe and Mail, the Canadian Association of Black Journalists, and Reddit was encapsulated in the report’s findings, which mention “polarized responses” to the revenue-sharing ideas. “There is a difference of views in terms of what would be the best model,” agreed then minister of Canadian heritage Steven Guilbeault when I asked him about the disparity between different types of media organizations (broadcast, print, digital, think tanks), old and new platforms, and large and small voices. “Everyone agrees that the status quo is untenable,” he maintained. “Some people would say we prefer a versus b, but everybody says, ‘You have to do something.’ You may not end up doing what we would have preferred. It’s better than nothing.”

Since the presidency of Donald Trump, it’s become common to talk about the relationship between the media and democracy. “Without a healthy media sector, we cannot have a healthy democracy,” said Guilbeault. “Whenever authoritarian or dictatorial governments want to take control of a country, to quash opinion, the first thing they go after is media. We’ve seen it happen.” This is what media scholars often call a “public good” problem. In other words, the media is so crucial to the state of democracy that we must protect it even if it isn’t economically viable. Similar collective decisions have had to be made in the past with respect to funding for street lighting and public libraries—things without which, we agree, our quality of life would be dimmed. There are challenges, however, to thinking of media as a utility, like electricity. The product on offer from power companies the world over is the same, but no one kind of media is like any other. For the purposes of this debate, should the National Observer, Canadaland, and Rebel News be treated the same way?

Canadians, despite having grown up with the omniscience of the publicly funded CBC, are relatively tetchy about the notion of government intervention in media. Last June, the Department of Canadian Heritage tabled Bill C-10, proposed legislation aimed at the intellectual-property obligations of streaming networks like YouTube, Spotify, and Netflix, which operate in Canada but are not subject to Canadian content regulations. Sparking a challenge from mostly conservative critics about the risks to free speech and the complications of federal meddling, the bill was struck down in the Senate.

In July 2021, The Logic CEO and editor-in-chief David Skok wrote an eloquent editorial in response to announcements that Facebook and Google had both signed licensing and / or promotion agreements with Canadian publishers—which many took to be preemptive contracts in advance of the Liberals’ proposed legislation. “This is not simply private-market players paying fair-market value in exchange for products,” he wrote. “It’s private companies using their trillion-dollar market caps and immense bargaining power to steamroll an entire sector in pursuit of their own self-interest.” In other words, can we trust the Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star—which both signed on with Google News Showcase, a licensing program that will promote stories to help boost paid subscriptions—to cover news of regulation and the GAFAs reliably? Will their deals be sweeter than those of small outlets with less bargaining power? Transparency concerns were also raised about the Australian model, in which the government may have overseen the contracts but the terms of the agreements between media outlets and GAFAs were not made public. (To avoid making payments, Facebook initially declared it would make its services unavailable to Australians.)

To be honest, I’m not that worried about objectivity in professional journalism: media has always been funded by someone, whether a beauty brand or an automaker—it just hasn’t been the customer. (The Walrus, not included in any of the aforementioned deals, has partnered with Facebook to produce The Walrus Talks and other events. There is no relationship between Facebook and our editorial content.) My worry is different: Is it enough money? If those payments covered 10 to 20 percent of the cost of journalism, which is analogous to what advertising might bring in for many outlets these days, it’s still not a lot to run a company.

In his 2019 book, The Tangled Garden, Richard Stursberg, who has helped lead Telefilm and English services at the CBC, compared the depth of Canada’s investment in news with what we spend on film and television—which we fund via tax credits—and found it wanting. For years, the government has subsidized Canadian cultural products to protect them from the US market’s dominance. Should our media receive the same protection from Silicon Valley–based tech companies? “To provide news with the same level of support as entertainment,” he wrote, “would cost the federal treasury about $430 million per year, $200 million for the papers, $30 million for magazines . . . and $200 million for TV news.” In 2018, the federal government allotted $45 million in tax credits to the news industry. New legislation in June 2021 enables “qualified organizations” to claim up to 25 percent of their labour costs in tax credits—currently, 156 outlets meet the designation. Stursberg’s proposed $780 million in tax credits (just over half of the $1.5 billion allocated to media in France, which has double Canada’s population) would be a net increase to news organizations.

I recently asked Stursberg if his views had changed in light of Canada’s movement toward requiring GAFAs to negotiate payments to media outlets, and he held true to his thinking: he prefers the grand gesture. “Why wouldn’t we treat news the same way we treat cooking shows?” he asked. “Surely news is as important to us, as a country, as drama or kids’ shows or comedies.”

Every player in the current ecosystem seems to envision a benign funder somewhere else picking up the tab.

“These are emergency measures. This is not a long-term plan,” admitted Guilbeault about his department’s recent proposals, which include a controversial $595 million to create jobs at select news organizations (critics alleged that too much went to legacy media outlets within the traditional print news industry), set to end in 2023. “I really think we have to figure out, together, how to ensure the sustainability and viability of the media sector.” When Guilbeault was appointed minister of environment and climate change in a cabinet shuffle this past fall, he was replaced by Pablo Rodriguez, who had previously held the role of heritage minister from 2018 to 2019. The government’s challenge is essentially to solve Canadian journalism’s wicked problem: Do we save what’s being lost or invest in what’s new?

As the editor of one of the country’s very few independent nonprofit publications, my primary frustration is with the lack of innovation in this country. Canadian journalism schools are pumping thousands of graduates annually into a market with dwindling employment opportunities. Some of these young journalists launch startups in different regions to bridge the gap between citizen journalist, blogger, and corporate media. But who is supporting them? There are no government programs designed to further the kinds of small-business development from which journalistic innovation is likely to emerge. To be effective, journalists need infrastructure: server space, website domains, software licences, contributor’s fees, image rights, a design identity, and sometimes lawyer’s fees. All that is before they can even pay themselves or anyone else a salary.

Facebook and Google both offer training and financial support to select media organizations. Facebook’s Journalism Project Accelerator Program and Google News Showcase provide fledgling newsrooms with crash courses in membership growth and audience engagement—skills crucial to building and retaining readerships. (The Walrus was recently accepted into the latest version of one of these programs, the Meta Journalism Project’s Canada Reader Revenue Accelerator, to begin in February 2022.) But their grants, which can range from $50,000 to $135, 000, function more like top-ups to existing budgets than like investment capital. Gone are the venture capitalist investors of the 2010s—perhaps because they sense that media’s a bad bet.

Earlier this year, an ambitious new outlet called The Breach was announced with testimonials from public figures like David Suzuki and Naomi Klein. The digital newsroom has better graphic design than most of Canada’s legacy outlets and an impressive commitment to publishing news, in-depth investigations, videos, and podcasts, including “the stories the traditional media is afraid to cover.” By my estimate, producing a bare-bones multiplatform “micro-newsroom” like The Breach would cost something like $300,000 to $500,000 a year. Not many recent graduates have that kind of money, and not many are in a position to pitch potential investors on a venture that, if it’s lucky, will probably only break even.

Because that’s where we are at. Journalism is an incremental, slow-to-develop business where success means staying out of debt in an industry where most struggle to do that. It has always been common for outlets to launch to fanfare, run through their start-up funding, and fizzle out before finding a sustainable revenue model. (The digital record is no better than print’s, from the Toronto Standard, an online newspaper that ran from 2010 to 2015, to various divisions of Vice Media.) In recent years, venture capitalists and private investors have stepped up to take over ailing media outlets only to step away when it became obvious that they were never going to scale up effectively. In early 2021, HuffPost Canada, which had operated in English since 2006, was abruptly shuttered after being acquired from Verizon Media by BuzzFeed.

The biggest success stories of the past few years, the outlets winning awards for their journalism and drawing in readers, are startups with focused offerings. Although their business models vary, all have matured past the premise of the internet’s early days—clicks at any cost, growth before everything. Xtra Magazine, a digital publication dedicated to LGBTQ2+ issues, grew out of Toronto’s print tabloid serving the Village and surrounding communities. Revenue from a dating app has helped it survive and grow. Now, more than 50 percent of its audience is outside Canada, and top stories range from deep dives on RuPaul’s Drag Race to how-to articles on talking to your kids about gay country singers.

The Local, on the other hand, is not trying to outgrow the Greater Toronto Area. Founded out of an innovation department at the University Health Network, it has a mandate to cover public health issues and to “impact” communities. The Local is funded by grants from seven community organizations, each worth at least $25,000. It also recently opened up to donations from readers. “Our bread and butter is hyperlocal,” says editor-in-chief Tai Huynh. However, the outlet’s influence is profound—throughout the pandemic, other publications scooped up its reporting on vaccine distribution, inequality, and front line workers in the GTA. “At this point,” says Huynh, “we want to do Toronto very well.”

The Narwhal, which has a mandate to publish environmental journalism, has seen astonishing growth for an outlet of its size. Founded in 2018 by two Vancouver Island journalists, the startup has grown its annual revenue fivefold, from $400,000 to just over $2 million, says editor-in-chief Emma Gilchrist. Now, with a staff of fifteen, The Narwhal has expanded to Ontario. The online publication received support from Facebook, which included it in an incubator program designed to help small newsrooms develop revenue-generating membership programs. The Narwhal is also a registered journalism organization, a new classification by the federal government that allows it to issue tax receipts to donors and receive grants from charitable foundations. (So far, there are only five such outlets in the country.) But its biggest success factor is converting readers to “members,” who contribute financially. Timely reporting on COVID-19 and in-depth coverage of relevant ongoing stories, like the Fairy Creek old-growth-logging protests, helped solicit increased donations from readers this year.

Now four years old, The Logic is the most venerable of Canada’s new independent digital startups. When it launched, its proposition was almost shocking: a subscription-only news publication with an annual $300 fee (about the same as an annual subscription to the digital Globe and Mail). “Canada had not reached the point where paying for news was in the public consciousness,” says Skok of his decision to fully paywall The Logic from the beginning. (In 2019, The Logic announced $1.8 million in subsequent investment from a handful of funders including Postmedia, a venture capitalist, and unnamed angel investors.) Because of the cost, many journalists can’t afford to read The Logic’s scoops; its audience is made up of the kinds of tech and financial analysts for whom the cost of membership is about the same as a Bay Street lunch.

A veteran of the Toronto Star and the Boston Globe and a fellow at Harvard University’s Nieman Foundation for Journalism, Skok keeps in mind that the New York Times took 150 years to become the world’s most recognized news brand. “We want to be the Financial Times [of Canada],” he says. For now, he’s proud of having built The Logic into an outlet people recognize as an authority on business. “It’s not about reaching the most amount of people. It’s about reaching the right people.”

It would be easy to keep listing independent digital startups in this vein—“ones to watch” that are making their investors proud. But an industry cannot live by plucky new websites alone. According to MediaSmarts, a digital media literacy organization, 43 percent of Canadians ages eighteen to twenty-nine get their news from Facebook, and the next largest sources are TV (12 percent) and Twitter (10 percent). Most of the population isn’t served by, or looking for, this kind of media at all.

“The Walrus, iPolitics, National Observer—none of you even show up,” says Winseck, referring to the market share information his team collects through the Canadian Media Concentration Report. “Audience reach is less than 1 percent.” This means that a fraction of 1 percent of the population is consuming news from the kind of place you’re reading and I’m writing for right now. Accrual of readership is like watching the interest grow in your savings account. Most Canadians get their news from big outlets like the CBC, Postmedia, Torstar (publisher of the Toronto Star), and CTV—the same legacy outlets that continue to struggle.

Realistically, only a small percentage of the population is likely to financially support independent journalism. Nonetheless, that is the model behind Substack, one of a handful of newsletter platforms that promises to cut publishers and distributors from traditional journalism by delivering revenue directly to writers in exchange for a cut of their subscription fees.

Substack doesn’t think it’s the answer to mainstream media’s problems. “We’re not claiming that this model will work for all types of news, and we don’t think it should be the only model,” says the platform’s statement of purpose. Substack, which was started in 2017 by a Canadian named Chris Best, “is not necessarily the sign of a healthy media climate,” says Jen Gerson, who turned to the platform a year ago to co-found The Line, a conservative-leaning political newsletter, with journalist Matt Gurney (both have contributed to The Walrus).

Because I’d heard some Substackers say they found the task of reporting, editing, art direction, and social media promotion all-consuming (gratifying news to anyone running a professional newsroom), I asked Gerson, previously one of the country’s most active freelance journalists, how she was finding the workload. “If you treat it like a part-time job, it works,” she said. The Line has 8,500 paying and nonpaying subscribers, who receive newsletters three to four times a week. “We will probably be close to making a full-time salary in a year or so.” (Which, for a nascent business founded in a dying industry, sounds impressive.)

Most of the people on Substack will reach audiences because they’re already successful journalists or brands; last year, Substack reportedly offered high-profile writers $250,000 (US) advances to populate the platform. Their success is exhilarating. But the Substack model faces the same challenges as all journalism everywhere: to build a reputation requires time, resources, and skills inaccessible to most amateurs. Newsletters also tend to emulate the kind of quippy op-ed writing that abounds on the internet already. Investigative journalism, on the other hand, is one of the most trusted and valuable forms of media, but it’s also one of the slowest and most expensive to produce.

What emerges is that every player in the current ecosystem—journalist, consumer, platform—seems to envision a benign funder somewhere else picking up the tab. No one has developed a price for journalism that a critical mass of customers is willing to pay.

Reliable media, like nutritious food, should not become a luxury product. But, in some ways, it already has. According to a 2020 Ipsos report, 70 percent of Canadians “strongly” or “mostly” agree that they will consume only news they can access for free. If trends continue, the future of media will probably be very big and / or very niche: well-known brands like the Globe and Mail and the CBC on one side, a number of independents or specialized outlets on the other. At worst, high-quality journalism will be available only to people who can pay for it.

It’s a world where some people subscribe to the New York Times and other members of the Trust Project (a consortium of fact-based media organizations to which The Walrus belongs) and others think the cure for COVID-19 is a folk remedy they saw on Facebook. What may be gone are the TV stations, city newspapers, radio stations, and even generalist news websites launched in the internet’s first flush—those middle-tier outlets and the programs whose perspectives are not essential in the age of social media, aggregators, and streaming. Maybe that’s not as big a loss as it once was. Our very idea of “the media” is changing. A lot of the news I read on my iPhone is curated by Apple News editors. If audiences once treated outlets as authorities, we now follow news based on its relevance to our interests.

One of my initial questions was whether the government should invest deeply in the CBC—to restaff its bureaus with the reporters and photographers who have been lost to cuts. That would be the quickest way, to my mind, to reverse the tide of misinformation and distrust in media across the country and to bring back coverage to communities like Cut Knife. Many people dispute that consolidation at one outlet is the answer—even those who might have a vested interest in public broadcasting’s success. Jennifer McGuire, who, after eleven years, left her job as editor-in-chief of CBC News in 2020, just spent a year studying collaborative media models at the University of Oxford’s Reuters Institute. She says media outlets should find more ways of co-operating—in Canada, major news organizations already share photography and reporting during the Olympics and elections. One such program, called the Local Democracy Reporting Service, is underway through the BBC, which hires local reporters to cover stories picked by other journalists and shared on open-source networks.

What’s been clear all along is that the media is suffering from a collective-action problem: everyone who normally thinks of themselves as rivals should be working together. But, as we turn this thing around, the weight of the media’s future is significantly being carried by the reporters, photographers, and producers who got into the business because they wanted to make a difference. How insurmountable it feels to ask people to report the biggest issues of our time—war, racial inequality, disease—at salaries that no longer cover the cost of an apartment in Toronto or leave room for a life outside of work. Add in something like the COVID-19 pandemic and resilience is being pushed to the brink. I can’t promise young journalists the career this industry has given me.

I didn’t expect this to be a referendum on my career, but that’s what reporting a story on the future of media turned into. Senior media executives talked to me off the record or on background because they didn’t want their personal pessimism attached to their professional titles. Everyone who had left the media altogether said they were so glad to be out of this terrible business. Everyone also urged me to keep going for as long as I can manage. “It’s a vocation,” said Irene Gentle, until 2021 the editor-in-chief of the Toronto Star. “If there are moments where you lose it, struggle with your role in it, that’s normal. If you have that sense of vocation, you’ll generally come through the other side.”

For those of us who have chosen it, the job at hand is to steer an industry through a transition, one as significant for us as the invention of the automobile in its own day. We know that the benefits of our work may not be felt for years or generations. Making Big Tech pay the media for content, as the government hopes to do, is only the beginning. It will also take serious policy change and industry collaboration to turn around a situation that’s been deteriorating for decades. “If you step back and look at it,” says McGuire, “you’ve got everybody doing little things to solve a problem that is humongous.”

The O’Hagan Essay on Public Affairs is an annual research-based examination of the current economic, social, and political realities of Canada. Commissioned by the editorial staff at The Walrus, the essay is funded by Peter and Sarah O’Hagan in honour of Peter’s late father, Richard, and his considerable contributions to public life.

After this story appeared in print, The Walrus was accepted into the Meta Journalism Project’s Canada Reader Revenue Accelerator program. The piece has been updated to disclose this new partnership.

Correction December 14, 2021: An earlier version of this article described The Logic as being funded by an unnamed angel investor, among other funders. In fact, The Logic has a number of unnamed angel investors. The Walrus regrets the error.

Correction December 16, 2021: An earlier version of this article stated that readers of The Narwhal can declare the cost of news subscriptions on their taxes. In fact, while registered journalism organizations can apply to offer tax credits for digital subscriptions, The Narwhal does not offer subscriptions. The organization can, however, provide tax receipts to donors. The Walrus regrets the error.

Correction December 20, 2021: An earlier version of this article described MediaSmarts as being a youth literacy organization. In fact, MediaSmarts is a digital media literacy organization. The Walrus regrets the error.