Darius had been away for a week when I started smelling gas in the kitchen of his parents’ house. We’d been staying there the past six months, tending to their new property while they took care of business in Iran. Once I checked that the burners were turned off, I asked him whether I should call the gas company. He told me to ignore it. The neighbours were building a new house, uglier somehow than the other McMansions lining Forest Hill, and Darius said the smell probably had something to do with their construction.

The next day, the smell of rotten eggs was stronger. I opened the back door of the house and went upstairs. The neighbours had recently installed scaffolding that looked directly onto the toilet. I’d placed a piece of cardboard over the window, but it kept falling down. Every time I peed, holding up the cardboard with one hand, I tried to ignore the sound of men’s voices murmuring on the other side of the wall, the scraping of trowel against mortar.

Shouldn’t the smell be gone by now?

Darius didn’t reply. He was in Qazvin, visiting his father’s factories, which manufactured items related to the oil and gas industry: measuring devices, turbines, mouldings for giant train wheels. Taking care of the house felt like a test, one that would determine our future, somehow still tentative after two years together. I didn’t text again, not wanting him to think I couldn’t be trusted with this simple task.

I called the gas company, but the recorded message said to call the emergency line if I smelled gas. I googled natural gas poisoning, side effects of which included dizziness, headache, nausea, and fatigue, all of which I’d attributed to the ordinary malaise of unemployment after grad school.

The man on the emergency line sounded bored, and when I explained I had smelled gas, he asked how old I was. I couldn’t be alone in the house with the technician if I was under eighteen. I was thirty, but my voice often adopted a girlish lilt when speaking to authority figures.

A worker arrived within half an hour and asked if my parents were home.

“It’s just me,” I said, tripping over his workboots as I directed him to the possible culprits: the stove and fireplaces, the outside barbecue, the heater for the pool. I wanted to explain this was my in-laws’ house, that none of this luxury belonged to me.

He traced a wand-like device along the cracks and crevices, the machine beeping every so often. Finally, he followed me into the boiler room in the basement, running his wand along the water heaters, where it emitted a series of beeps in quick succession and discovered a tiny leak in the hose that connected the gas to the water heater. He would have to turn off the gas and I’d have to call a contractor to come and replace the hose.

“Can’t you just fix it?” I asked.

“I don’t have the tools for that.” He went outside to turn off the gas valve and gave me a yellow sheet to show to the contractor.

When I called Darius, complaining that now I couldn’t even take a hot shower, he asked why I hadn’t waited for him to come back and deal with it.

“I didn’t want the house to explode on my watch.”

“A small amount of leaking is normal,” he said. “Did you forget my dad works in the gas industry? It’s perfectly safe.”

I went upstairs, using the last of the hot water to bathe. When I got out, I didn’t drain the tub but left it for later, something my mother had always done. There was never enough hot water for our family of six, so she left her bathwater for me. I had no one to save the bathwater for, and when I came upstairs that night, the water had become lukewarm. I went to sleep without draining the tub.

The contractor couldn’t come until late the next afternoon, even after I explained the urgency of the situation. It was cold in the house without the heat, and I layered a hoodie over a turtleneck.

Darius told me to go outside and turn the gas back on myself. Since it was such a minor leak, he didn’t think the gas company had locked the meter. I resented how Darius always flouted the rules. He was often ticketed for parking at the supermarket before riding the subway to work, saving himself a fifteen-minute walk through the ravine. He’d even gone to traffic court to dispute the charges until the traffic cops revealed they had photographed every infraction.

Go take a picture and I’ll tell you what to do, Darius wrote.

The construction workers were on the scaffolding and I didn’t want them to see me sneaking around. I waited until they were on a break—eating sandwiches wrapped in foil in their trucks parked along the street—and peered around the corner. The owner was perched on the edge of the scaffolding, scrolling on his phone. I stepped forward tentatively, a blue plastic tarp crinkling underfoot. He looked up, giving me a nod. I photographed the gas meter at the side of the house before scurrying back inside.

It doesn’t look locked, Darius said. He told me to turn the valve and see what happened, but I was too afraid of gas leaking out. Through the front window, I watched the workers returning from their breaks, flicking cigarette butts into our yard.

What if the heater explodes?

It doesn’t work that way, he replied.

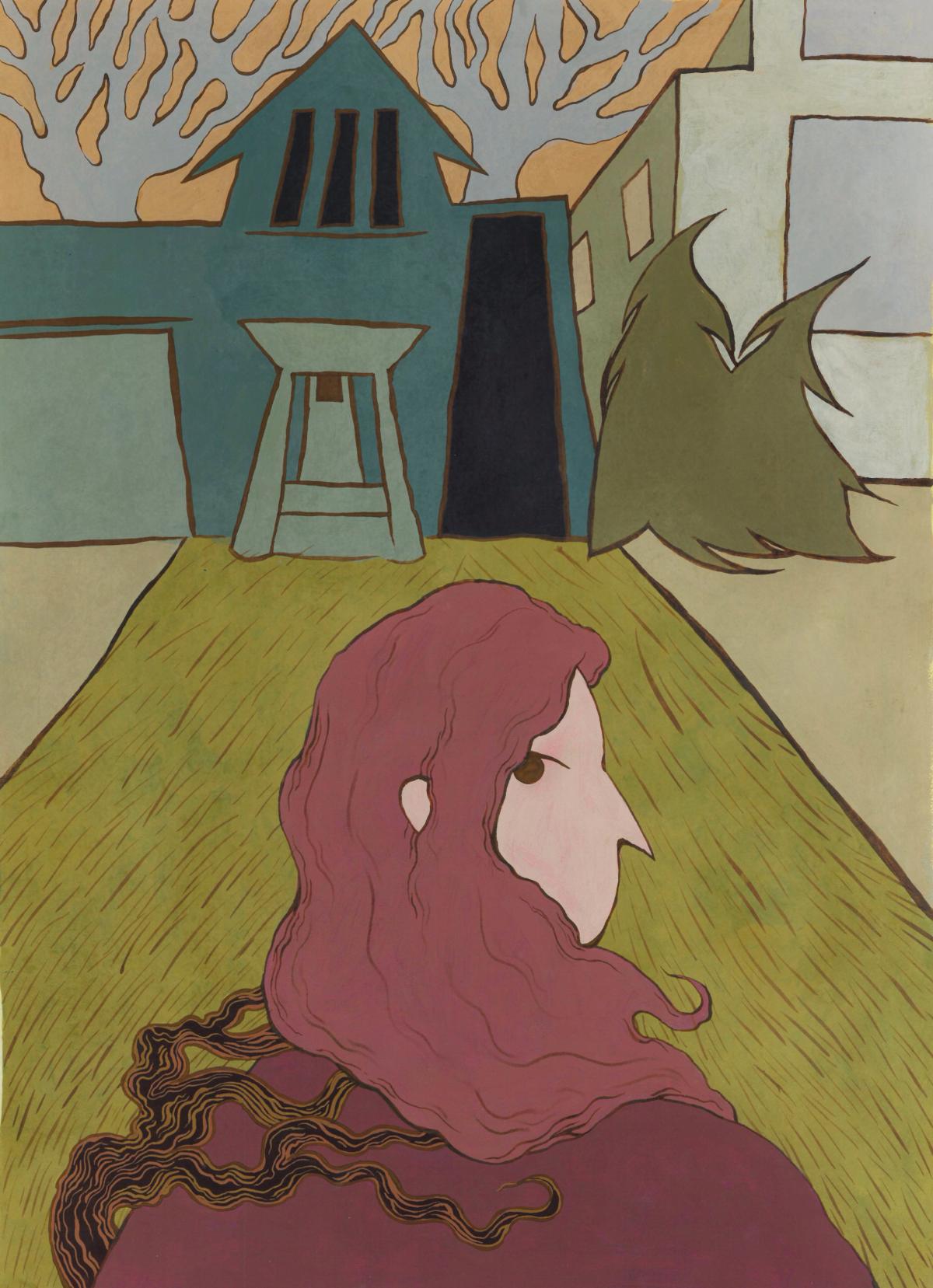

Something in me resisted doing this simple thing. Darius often lamented my rigidity, but I knew it more as fear, an inability to step into the unknown. Even something as simple as opening the curtains each morning and closing them each night—a task my mother never neglected—felt overwhelming. Most of the time I left the house dark all day or kept the curtains open for days on end.

I’ll just wait for the contractor, I wrote back.

The stink of garbage followed me around Forest Hill, but it wasn’t garbage day. I thought I was smelling the trash that teams of construction workers scattered on the street, or porta-potties with names like Black Tie Toilets and The Jackpot. I stopped to photograph one porta-potty bearing a cartoon illustration of a leprechaun with a pot of gold on the lawn of one McMansion. A black SUV was idling in its driveway, and the side of the vehicle displayed a pair of angel wings, the logo of a private security firm. I had seen similar SUVs circling the neighbourhood, and I wondered if my presence drew their suspicion.

I walked through the ravine to the hardware store for flower seeds. I’d recently come across a photo of the marigolds my mother had planted in our backyard. I had visions of planting flower beds of bright yellow and orange marigolds like she had, but first I had to weed the plot of dirt at the end of the driveway. Every other house hired landscapers for their perfectly trimmed hedges and mowed lawns, but Darius refused to pay for something we could do ourselves. He suggested weeding would give me a nice break from applying for jobs, a way to make his parents’ house feel more like my own.

When I examined the display of seeds at the hardware store, I realized it was too early in the season to plant marigolds. The seeds should be planted after last frost, and it wasn’t yet April. I could plant them indoors and then move the seedlings outside, but I doubted my ability to keep anything alive in the dark house.

I googled the hardiest flowers—coneflowers and hostas—and selected a handful of wildflower variety packs, unsure how many I would need for the small strip of dirt.

On the walk back through the ravine, my fantasy drifted from a colourful summer oasis to a useful plot of native wildflowers. When all the other flowers in the neighbourhood were dying, mine would still be attracting butterflies and bees. I started sweating as I climbed the hill back to the house, and passed landscapers, joggers, and nannies with baby strollers.

At the top of the hill, a roofer yelled something down to his co-worker. My father had worked as a roofer and so had my grandfather. I averted eye contact, keeping my gaze fixed on the sidewalk and, when it abruptly cut off, the brick street leading to the house.

Digging out the flower beds was more challenging than I had anticipated. It felt productive to pull out the dead weeds, but the soil underneath was densely packed together. As I dug deeper, I realized the flower beds had once held a row of hedges, just like the ones at the back of the house. The previous owners must have removed the hedges, but they’d failed to dig out the system of roots underneath.

I retrieved a pair of gardening gloves, a trowel, and a rusted pair of clippers from the shed. Just as I was setting up my tools, the contractor called to say he couldn’t come until the next day. I reminded him of the urgency of the situation—I had no heat or hot water—and he told me he’d arrange to send someone out first thing the next morning.

I took my annoyance out on the garden and spent most of the afternoon digging out the dirt and pulling on the thick roots, which grew intricately together. I used the garden shears to sever one thick branch, revealing a green core—the hedges were still alive, leeching nutrients from the soil. It would be difficult for any wildflowers to grow atop the remains of the hedges; I needed to pull out the remaining roots before I could plant anything new.

My hands soon became sore, and I could feel blisters forming. Finally, I pulled out one thick network of roots, unearthing all matter of beetles, earthworms, and centipedes. Below this lay a system of smaller roots like fine lace, knitted into the dirt. As I pulled out this bundle of dirt and matter, the tiny roots tore like threads of hair.

Some sort of spider had woven a web underneath the dirt, I realized. I was pulling apart the threads of a massive web, and I feared coming across the exoskeleton of the creature that had woven it. I froze, scanning the dirt for the movement of tiny legs. A dark ball of something scurried across the dirt, its legs moving too quickly for me to discern its shape or size.

Frantically, I began shovelling the dirt back on top of the web, first with my trowel, and then by hand. I dragged the bag of topsoil out of the shed and covered the network of roots with the fresh black dirt. Then I patted it down, sprinkled the dirt with water from the hose, and scattered the wildflower seeds overtop.

My clothes were covered in dirt and I was sweating from physical exertion. When I stepped back, the driveway was covered with splatters of topsoil. It looked like a dog had dug up the yard, a mess beside the neighbour’s immaculate Zen garden. I messaged Darius that the weeding was too much work to do on my own.

Just do your best, he replied. I’m not expecting magic.

I went upstairs to clean up, but the bathwater I’d saved from the night before had gone cold. My fingers were aching from pulling on the hedge roots, and I yearned for the comfort of a long bath. I turned on the water tap, and was surprised when hot water—not just warm—poured out. The water tank must have kept its reservoir heated.

I ran myself a shallow bath, conserving the hot water that remained, and lowered my body in the tub, gently washing my hands, revealing a line of red blisters where I’d pulled on the roots. The blisters stung as I washed them. This time, I drained the water, cloudy with detritus, wiping the dirt out of the tub with a paper towel.

I woke to the doorbell shortly after 8 a.m. I hadn’t set an alarm and I dressed quickly in sweatpants, my hair a mess, and ran downstairs, opening the door to a college-aged contractor wearing a baseball cap and Adidas track pants.

I showed him the yellow sheet that the gas company had issued me, and explained what had happened: I thought I’d smelled gas, and called the gas company. They’d found a leak and turned off the gas, which is why I’d called him to come fix it.

“Are you the homeowner?” the guy asked, peering behind me.

“My boyfriend is,” I said, realizing too late that letting a strange man into the house might be unsafe. “He’s at work.”

The contractor nodded and I led him down to the boiler room. I wondered if I should ask for his ID, but I didn’t want to offend him.

“They do a pressure test?” the guy asked.

“I’m not sure,” I said. “But he found a leak.”

I showed him the yellow pipe connecting the gas pipe to the water tank where the gas guy’s wand had started beeping.

“We’d have to do a pressure test,” the contractor said. “But even if we find the leak, we won’t be able to fix it.”

“But that’s why I called you,” I said. “I explained all of this to the person on the phone.”

The contractor showed me a tag affixed to the water heater with a zip tie.

“This is a rental tank,” he said. “Because you’re renting the water heater from the city, we can’t legally touch it.”

He traced his hand along the yellow hose, which looked rusted and worn.

“This is us,” he said, tapping the metal gas pipe leading from outside. “And this is them. We can’t touch anything past this line.”

“You can’t just fix the hose?” I asked. “I think it just needs to be replaced.”

“You’ll have to call the city and have one of their guys come out.”

The contractor left, but not before charging me $110 for the house call. I called Darius to complain, and he told me I should have just turned the gas back on as he’d told me to do in the first place.

“Do you want me to call the neighbours to do it?” Darius asked. “Anyone who works in construction does this sort of thing every day.”

“The gas company made it sound serious.”

“Do you know how my dad checks for gas leaks?” Darius asked. “With a match.”

“I’m not going to wave a match around,” I said.

“You can also use soap bubbles. It’s actually quite fascinating.”

I called the number on the tag attached to the water heater, but they had no appointments until Monday, even after I explained the yellow tag and the cold house. I felt myself beginning to despair, unravelled by bureaucracy. I wanted to take another bath, but needed to conserve the water. For dinner, I made myself a salad with the random assortment of vegetables in the fridge: raw cauliflower and celery, pickled beets, boiled potatoes, iceberg lettuce, black olives, whole grain Dijon mustard, mayonnaise.

It was a similar meal to the one Darius had made me after my mother died. My father had called to say what happened, and then I’d called Darius, who left work to meet me at my apartment. I’d hyperventilated down Bloor Street, sobbing uncontrollably until we reached his sublet on Palmerston. There, I’d collapsed on the pink velour sofa and he’d made me this disgusting food, as inedible now as it had been then.

The next morning, I woke to the sound of someone sobbing. I rushed downstairs without my glasses, expecting to find a blurry outline of Darius weeping on the floor. I worried that there had been an accident at the factory, and he’d needed to come home early from his trip.

But when I came downstairs, no one was there. Nothing had happened and no one was crying. I dressed and watered the garden plot, pressing my thumb over the nozzle so the dirt wouldn’t spray everywhere. I returned the hose to the side of the house, which faced a stone and half-timbered cottage where an older couple lived.

I watched as a wrinkled hand reached out of the basement window. The hand was trying to put the window screen, which had fallen to the cement, back into place. I could have held the screen in place, but the hand achieved its task and pulled itself back inside the cottage.

In the ravine, a group of small children dressed in red vests and pointed hats were running back and forth with plastic buckets. They looked like elves and I resisted the impulse to photograph them. At the store, I bought crackers, hummus, carrots, and other items I could eat at room temperature. I lingered at the yogurt tubes and string cheese, the tubs of applesauce.

When I returned to the house, the neighbours were using a construction crane to move a pool over Darius’s house and into their backyard. I had to stay outside until the process was complete. The owner, giddy with excitement, squeezed a yellow hard hat tightly over my forehead. The pool had been precisely built to the yard’s specifications, he explained, which allowed him to simply slot it into place.

I sent Darius a selfie with the hard hat as well as a picture of the pool floating over his house. In response, he told me to take a video; what the neighbours were doing was illegal. They were supposed to get approval from the city, and he hadn’t signed anything.

I was taken aback by his sudden adherence to the law, but dutifully recorded the procedure. When it was finished, I left the hard hat on the curb and went inside with my groceries. As I unlocked the door, I saw another arm coming out of the older couple’s cottage, this time from the upstairs window, pulling back a curtain that had blown outside.

I thought of the spiderweb I had seen under the flower garden, the sound of someone weeping downstairs. I googled gas leak hallucination. One side effect was memory loss and confusion, but hallucinations were rare, and besides, the gas company had turned off the gas.

I didn’t tell Darius what I thought I had seen or heard.

The next day, the garden plot was covered in a layer of frost. The cold snap had killed my seeds, no matter how hardy. I had just enough time to buy more seeds before the city contractor arrived. I hurried through the ravine, failing to take in the beauty of the hoarfrost covering the branches, the crystals gleaming in the sun. On the way back, I reached the brick road that led to Darius’s block when I heard what sounded like a horse clopping.

I looked up to see a child dressed as a princess riding a miniature pony. A woman in overalls was leading her on a rope. The residents of a newly built home had converted their yard into a petting zoo for their child’s birthday, fencing off goats and llamas, a donkey, an array of fluffy white rabbits. I stood at the periphery of the petting zoo, discreetly taking a photo.

I looked up as one of the mothers smiled stiffly.

“Excuse me,” she said. “Are you photographing my child?”

I reddened, suddenly aware of the security guards idling in their SUV down the street, the group of parents surrounding the bouncy castle, sipping from reusable mugs.

“I was taking pictures of the animals,” I said.

“Are you sure about that?”

“You have to admit it’s a strange sight.”

“What’s so strange about a birthday party? I’m going to have to ask you to delete them.”

I began to walk away, embarrassed by the encounter.

“Do you even live in this neighbourhood?” she called out after me.

“Who cares if I do?” I called back. “You don’t own the street.”

“You’re lucky I’m not calling the police.”

I stopped and turned back. “Do you even have a permit for any of this? I’m sure the city has rules and regulations about setting up zoos on public property!”

The party guests were now staring at us. A braying goat sounded like a person wailing.

“Psycho,” the woman said, picking up a small blonde child with fairy wings.

I didn’t look back until I was at the house, walking the entire way as though a horse was at my heels and I would feel the hot air of its snout if I slowed down for a single moment. When I finally reached the orange dumpster marking the neighbour’s yard, I turned, but no one was following me. The street was completely quiet.

I entered through the back door and took a shower, turning the tap as cold as it would go. I held my breath and let the cold water fall over my face and nostrils, calming my breath and slowing my heart rate. It was a tactic I’d learned in the mindfulness class I’d taken after my mother died. I was reassured by how well it worked, as if underneath the layers of my anxiety, I was merely a panicked animal, ruled by instinct.

I dressed and made myself tea, reading the label as it steeped: skullcap is traditionally used as a mild sedative and to help relieve nervousness. The mail slot clattered and I jumped at the sound. I worried it was the woman leaving me a threatening note, a cease and desist she’d had her lawyer husband draw up. I found only letters from a wealth management company addressed to the previous owners. I put the letters in the trash.

A few minutes later, the doorbell rang. I welcomed the arrival of the city contractor and launched into the gas leak saga with a manic fervour: a few days earlier I thought I had smelled a gas leak and called the emergency line. The gas company found a small leak in the water heater and turned off the gas valve. I called a contractor, who couldn’t fix the leak because the water heater was rented from the city. I now needed the city contractor to fix the gas leak so I could call the gas company and get the gas turned back on.

It seemed like an easy fix, replacing the rusted old hose with a shiny new one. But even after the city contractor finished working, he wouldn’t turn the gas back on. He explained I would have to call the gas company to come back and do a pressure test, ensuring that there were no other leaks, and he didn’t have the equipment to do the test.

“Can’t you just wave a match around?” I asked. “Or use soap bubbles?”

“Most leaks are inside the walls,” he said. “I couldn’t find them even if I tried.”

“I’ve been dealing with this for almost a week,” I said, my voice adopting that pathetic childish lilt. I showed him the yellow sheet the gas company had issued, but he was unmoved.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “There’s nothing I can do.”

I turned away so he wouldn’t see me crying, and he followed me upstairs, where he asked if I wanted to pay the invoice now or have it added to the monthly gas bill.

“Just add it to the bill.”

That night, I dreamed that a pool teetered over the house on a tall crane. I was inside the house when the pool fell. The pressure collapsed the roof, water flooding the bedrooms. The only way out was through the windows, but when the neighbours’ hands reached out of their windows, my arms were too short to reach theirs.

I woke to the sound of the doorbell. It was the neighbour asking if his guys could get into the backyard. They needed to access an electrical wiring panel.

“Sure,” I said. “That’s fine.”

I texted Darius, and he told me to keep an eye on them. I set up my laptop at the kitchen table as I scrolled through job listings, looking out every few minutes to see the workers setting up a ladder at the back of the yard and then climbing it.

The next time I looked out, one of the men was on the patio, holding a cigarette to the barbecue.

“Hey!” I called out the door.

“Sorry,” the guy said, turning off the barbecue. “I needed a light.”

“It’s not that,” I said, stepping outside. “I’ve been trying to get my gas turned back on all week.”

“Well, it’s working fine,” the guy said, taking a puff. “You’re sure they turned it off?”

“I thought so,” I said, suddenly doubting myself. “At least I think that’s what he said.”

“Did you try your stove?”

He stood at the door as I turned the dial, hearing the clicking of the pilot light before the burner lit up in a whir of blue flame. The guy picked up the yellow sheet from the table.

“Yellow just means there’s an issue you have to fix in the future,” he said. “Now if they red-tagged it, you’d have a real problem. Yellow’s not that serious.”

“I should have googled it,” I mumbled.

The guy went back outside and I called Darius on FaceTime. “I feel so stupid—the gas was on the entire time.”

“What do you mean?”

“The gas company never turned it off. I was gaslighting myself all week!”

“So you can shower now?”

“I could but the water heater’s still off.”

“So go downstairs and turn it on,” Darius said.

I lost service as I went down to the basement. I turned the lever that connected the gas pipe to the water heater. The next step was turning on the heater itself. I stared at the button, but something held me back.

I thought of how, when I was a child, our furnace often turned off in the night when it was minus thirty outside. My father worked the night shift and so it fell to my mother to wake at 6 a.m., go down to the basement, and turn the furnace back on. My mother had never been afraid of holding a match to the pilot light. I didn’t know what had made me so cowardly. There was a small rattling sound as I turned on the water heater, and a light came on. I exhaled, and ran upstairs.

I turned on the shower, the window fogging up as I undressed. I stepped into the chamber, where peals of water hitting the granite made the sound of a woman singing from a distant radio. I wondered whether something had malfunctioned in the neighbour’s house, if the electrical wiring had somehow broadcast music into ours. It took me a moment to realize the sound was coming from the showerhead itself, that the woman’s voice was being emitted from the pipes, music raining over my body.