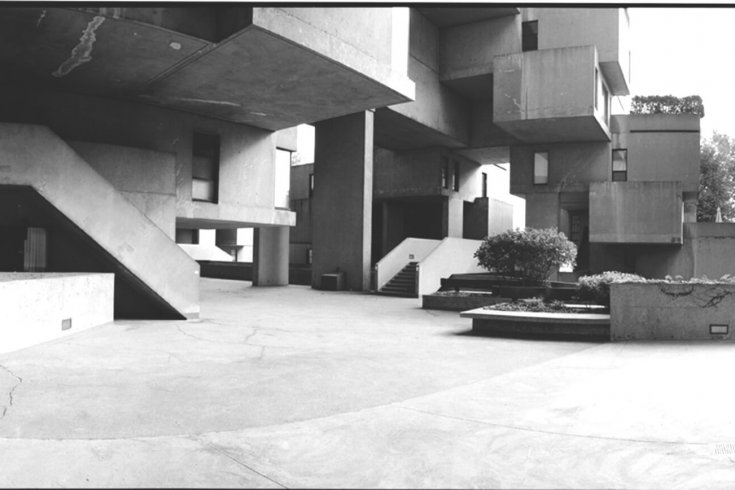

If you drive past Montreal’s industrial waterfront to 2600 Avenue Pierre-Dupuy, you’ll confront one of the most fantastic experiments in twentieth-century architecture. At Habitat 67, raw concrete catwalks and cantilevered blocks hover above, overlapping and interlocking; forms jut and recede in and out of your visual field like a cubist painting come to life. But Habitat was never touted to be something as trivial as mere art: this ten-storey apartment complex once promised an architectural revolution that would bring housing to everyone. Its resounding failure on that count says less about the structure, though, than it does about our collective self-delusion.

Built as the crown jewel of Expo 67, Habitat was Canada’s first truly ideological government-sponsored architecture. Erected on an artificial peninsula extending from the island of Montreal, it was launched as a manifesto for universal, affordable urban housing. At that time, four decades ago, Canadians foresaw a technology-driven future of endless prosperity and social harmony. Civil engineers served as social engineers, constructing a huge new infrastructure of highways, subways, and skyscrapers to ensure this collective happiness. In a giddy full-page ad in its flagship publication, Maclean’s, Maclean-Hunter proclaimed, “The next 100 years in Canada,” wherein cities would explode into “vast megalopolitan clusters of 25 to 50 million people,” with a universal two-day workweek, free local transportation, no pollution, and a pleasant monoclimate supplied by a huge transparent plastic membrane overhead.

In our own millennium, when “Modernism” denotes the rarefied taste of stylish bon vivants, it’s hard to imagine its original socialist goals. But the pioneers of Modernism—Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Adolf Loos, et al.—saw the movement as the salvation of the housing-starved underclass. The Modernists’ most naive conceit was that they thought they could design social equality into existence. Le Corbusier’s famous Marseilles Unité d’Habitation apartment complex was built in the hopeful aftermath of World War II, but by the 1960s was derided as a bleak, monotonous warehouse. Habitat, our own answer to the Unité, seemed as if it would be different. As futuristic as a dna model yet evocative of a Mediterranean villa, it looked like the perfect space age home. And it fit in perfectly with Expo’s faith in technology for creating a just, endlessly prosperous country.

This faith reached its zenith at the opening of Expo 67, which celebrated architecture, particularly the American pavilion’s geodesic dome, by Buckminster Fuller, and West Germany’s hyperbolically curved tent, by Frei Otto. But Habitat stole the show. When prime minister Lester Pearson rode the monorail through the fair, he could sweep one hand toward the array of architectural bravado and proclaim, as he did, “Anyone who says we are not a spectacular people only needs to see this.”

John Rae, executive vice-president of Power Corporation of Canada, like most of his fellow Habitat residents, recalls that era with a wistful fondness. “Expo was a time of hope, really, and innovation,” he says in a soft voice. “We are a very practical country, and this was a chance to become a little more daring. I don’t know of any other time Canada would have allowed this opportunity to a twenty-six-year-old with a vision.”

The visionary wunderkind was architect Moshe Safdie, who would eventually design showcase projects around the world, from the Ben Gurion International Airport near Tel Aviv to the United States Institute of Peace headquarters now underway in Washington, DC. But in 1967, he was just another brilliant McGill graduate with a thesis in his backpack. Entitled “A Case for City Living: A Three-Dimensional Modular Building System,” Safdie’s architecture school thesis was even larger and more fantastical on paper, but under the real-world constraints of the actual commission he distilled it to its core tenets. The complex would be assembled from prefabricated modules made in factories; as much as possible would be entrusted to machines, from the steel-reinforced concrete modules to the moulded-plastic bathrooms. Each rectangular module would criss-cross over another, so the roof of the one underneath would bear the load of the one on top, with the non-overlapping areas generating patches of outdoor space. As Safdie memorably promised, “For everyone a garden.”

The government would build the pilot project, then Habitat in turn would proliferate around the world. At least that was the idea. But Habitat 67 ended up as one big white elephant—for its architect, who garnered fame abroad and exile at home; for Ottawa, which struggled to brake the skidding costs of this “low-cost” model; and for the public, who were promised affordable housing but offered sky-high rents—when they were offered anything at all. It’s been a long and twisted road from there, and the fact that Habitat has now evolved into an enclave for the affluent is the final irony.

It’s ironic to everyone, perhaps, except for the man who created it. “The message of Habitat was that there is a magic solution that will be affordable for everyone,” says Safdie now. “This was a deep misunderstanding. When we built the building, we didn’t say low income, middle income, whatever. We said, ‘a new model for urban living.’ As a concept, I was not differentiating in my mind the idea of low and middle income as having different needs.”

Habitat denizen Frank Motter fondly remembers Expo—“every drunken minute of it”—when he was in his early twenties. He also remembers Habitat, and the promise of affordable housing for everyone. “That was a la-la story,” says Motter with a smirk. He should know: he’s one of Habitat’s pioneer residents, and a builder and developer himself. But anyone with even a passing knowledge of construction or real estate could have foreseen that nothing with Habitat’s gardens and piazzas and catwalks could be anywhere near as affordable as a conventional construction. “Look, you’ve got a foot of outdoor space for every foot of indoor space,” says Motter. “Right there, that’s double the cost.”

Habitat construction sucked up more than $22 million—$135 million in today’s dollars—for fewer than 200 small apartments, even though parts of each unit were subsidized by suppliers. Safdie and others defended the stratospheric costs on the grounds that this was a pilot project. Producing, reinforcing, transporting, and placing each module cost a lot of money; the embedded and indirect costs of catwalks, plazas, and automatic garden-watering systems drove the budget through the roof. But it eventually became clear that all that stuff would always cost a lot of money. As a world fair spectacle or as architectural research, Habitat was terrific. As a pilot project, it was a bust.

What happened? The short answer, as Safdie would later concede, is that the technology of the times was not yet in sync with his ambitious architectural approach. The long answer is more complicated, and in the end has much more to do with expectations than with architecture.

After Expo, Habitat stood empty for over a year. Flailing around to pay off the construction bill, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation first set the rents at astronomical rates: over $1,000 for some units, at a time when a pleasant two-bedroom townhouse could be had for a couple of hundred dollars a month. Making matters worse, cmhc was simply a lousy marketer. It eventually slashed the rents to $400 per unit, still high for the times. It was a money-loser for the government, and restricted to high earners.

Fast-forward four decades: these days, Habitat is one of the most coveted addresses in Montreal. To buy a 1,200-square-foot two-bedroom unit will set you back around $500,000—about double the price of a townhouse in central Montreal. Maintenance fees alone (which include a shuttle bus to ferry residents to the city) run around $1,200 to $1,500 per two-cube unit per month. To Safdie, Habitat’s exclusivity means not failure but success. “That shows it’s desirable,” he says. “To me, the gentrification of Habitat is the best thing that could have happened.”

Habitat is now infused with the city’s cultural elite: the top dogs in Quebec film, photography, and media. But more and more, it draws Montreal’s political elite, especially Liberal power brokers. The first was long-time resident Rae, not only a vice-president at Power Corp., but also brother of would-be federal Liberal leader Bob, and the rainmaker for all three of Jean Chrétien’s electoral victories. Rae, who heads the Habitat partners committee, is a member of what many locals refer to as the Old Gang—those who have been living at Habitat since before Ottawa threw in the towel and sold it off to the private sector in 1986. And when that sale took place, Rae and fellow Habitonian Frank Motter were ready to make the best of it.

When Ottawa put Habitat on the block in 1985, a tenants’ collective put in a bid of $9 million. It was swiftly trumped by Gatineau businessman Pierre Heafey, who offered the feds $10 million. Ottawa took it; then, in one deft move, Heafey flipped it back to the tenants for $11.4 million just three weeks later. Right after that, Rae and Motter teamed up with Heafey to snap up the units of those tenants who had declined to buy. These, in turn, they gradually sold to existing tenants. It was a shrewd, perfectly legal way to make a killing in real estate. But to many of the other tenants, it was a violation of what they had tacitly assumed was Habitat’s one-big-family, non-profit roots. “Rae runs Habitat like it’s Power Corporation,” wails Old Gang resident Lucette Lupin. “But it’s a community!”

Given the units’ rising prices, none of the long-time residents should have reason to weep. But that does suggest that Habitat as a great social experiment—community building through architecture—can go only so far in a market economy. “We don’t have the sense of community that we used to,” says another Old Gang denizen. To prove her point, she shows me a clipping regarding Jean Carle, from the Gomery sponsorship scandal inquiry, who recently moved into Habitat. (Gomery: “If this were a drug deal, it would be called money laundering!” Carle: “You’re not wrong.”) “See the kind of people that are moving in here now?” she says with a sigh.

John Rae’s 3,600-square-foot domain is a fusion of two separate units, and a jumble of decor themes. Walls are sheathed in patterned fabric. The tiny space age kitchen has vanished, replaced by a capacious piazza of granite and stainless steel. Other rooms are painted in emphatic hues of green and yellow ochre, and filled with ornate furniture. It’s a long way from Safdie’s original idea—actually, it’s pretty much a run-of-the-mill luxury condo—but so be it. “There’s a lot of romance about the original units,” acknowledges Rae. Sweeping one hand toward the huge, sumptuous new kitchen, he adds, “This reality is better than that romance.”

Rae is expounding from his favourite room, a former concrete balcony now paved with grey travertine and converted into a closed solarium that he calls “my oasis.” Other than the frequent phone calls that punctuate our conversation, the atmosphere is utterly serene. He steps up to one of Habitat’s signature windows, a long vertical strip like the window of a fortress. Beyond the geometric concrete are the whirling rapids—an eddy in the St. Lawrence River—where a gaggle of surfers have been hot-dogging and wiping out. Rae shakes his head slowly: “I never understood the business of surfing.”

Daring? Risk-taking? I suggest.

“Daring,” nods Rae. “Okay, now I get it.” And then he glides to the next room to take yet another call.

Daring—that was the quality that drew Habitat’s earliest residents. The complex’s radical appearance bespoke newness, verve, and progress. And yet the building turns out to be like a geode: its rough, plain crust gives no hint of the phantasmagoria you see when it’s opened up. For instance, Frank Motter’s complex is, like Safdie himself once wrote, “straight out of Playboy”—circa 1977. The living-room ceiling is coffered with hexagonal smoked glass framed by ornately carved wood. In the master bedroom, a large painting of a naked couple overlooks a rumple of sheets on the bed while, incongruously, the window opens onto a sober arrangement of concrete forms.

At Habitat, the contrast between the modernist, egalitarian exterior and the often-garish interiors is jarring. But this, according to Safdie, fits with the grand scheme of things, as he wrote after a 1986 follow-up visit: “Each resident had created his own world in his own image.”

Safdie’s own Habitat unit is a study in purity, boasting the architect’s original ideal of white-walled minimalism. From his balcony garden, you get a 360-degree view that reads like a history-in-the-round of modern Montreal. On one side, the once-expansive view of Mont-Royal is now crowded by a forest of office towers; on the other side is the graveyard of Expo, mostly razed except for America’s geodesic dome, whose skin burned off years ago, and the French pavilion, which has been transformed into a bustling casino.

The interior of Safdie’s penthouse has its own history: it was the vip unit at Expo, and later it evolved into a sort of guest house for visiting hotshots. As such, it has long served as a flagship, a symbolic reassurance for Habitonians. As one otherwise-content resident confides: “The day I hear that Safdie’s getting rid of his unit is the day I put my own on the block—because that means he knows something I don’t.”

Actually, it turns out Safdie may be getting rid of his unit after all, but not to make a profit or flee impending calamity. Studies are under way to restore his original unit to its 1967 perfection, with the aim of bringing it under the umbrella of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, though he has not commented on this publicly. But it would be a logical step for a Boston-based, globe-trotting architect, as he doesn’t spend much time there these days anyway. Maybe it’s time to move on.

Canadians have moved on, too, having long since packed up their faith in architectural determinism. On the social housing front these days, the paradigm is the transformation of Vancouver’s derelict Woodward’s building into housing “for everyone.” The affordability of Woodward’s, though, is predicated not on architectural wizardry but on dull workaday politics: tax breaks, subsidies, density bonuses, and finely calibrated ratios of robustly priced condos alongside “non-market” housing. It was designed by Henriquez Partners after a high-profile call for proposals. But it was the business savvy of developer Ian Gillespie and hyper-marketer Bob Rennie that sealed the deal. The free-market condominiums—already being flipped for profit—have effectively subsidized the low-income rental-housing units.

This is the new social housing paradigm, wherein the architect has been demoted in the public eye from visionary to a kind of amiable facilitator. As Woodward’s chief architect, Gregory Henriquez, puts it, “The program is the architecture.” Everyone knows that the downtrodden Downtown Eastside around Woodward’s will stay hospitable to lower incomes only if the government keeps pumping money and services into the neighbourhood.

But could Safdie’s paradigm find a place again in this architectural realpolitik? These days, new carbon-fibre technology could enable a new generation of Habitats on a wide scale, he says. Just as in old times, though, it’s way too expensive to make it worthwhile. But someday—who knows? “It’s too early for judgment day,” asserts Safdie. “Habitat’s day is yet to come.”