“All kinds of people have written books about half-breeds before,” said Maria Campbell in a 1973 interview with the Leader-Post, “but nobody who is a half-breed has written a book before.” Half a century ago, there were very few books published in Canada written by Indigenous authors. Aside from the work of Mohawk poet E. Pauline Johnson, most Canadians had likely read about Indigenous people only through the words of settlers.

That changed when Campbell published her memoir, Halfbreed. At the time, she was a mother of four living in Edmonton, deeply involved in the nascent Métis political movement that defined the 1960s. The book reads as an expression of her activism—a desire to represent her people and reveal the racism and dispossession that had pushed them to the margins and to galvanize them to work together in order to fight oppression.

The manuscript was originally 2,000 pages, which Campbell wrote in a cathartic fury, according to a 1973 interview with the Province. The manuscript landed on the desk of Jack McClelland, president of the Canadian publishing giant McClelland & Stewart, who, despite being initially guarded, praised Campbell’s writing but suggested substantial edits to bring the political purpose of the book into focus. (“Incidentally, I categorically reject the notion about leaving her style alone on sociological grounds,” he chided. “That is a blatant form of patronization and prejudice and totally inapplicable.”) But, he added, “she has the nucleus of a truly remarkable book.”

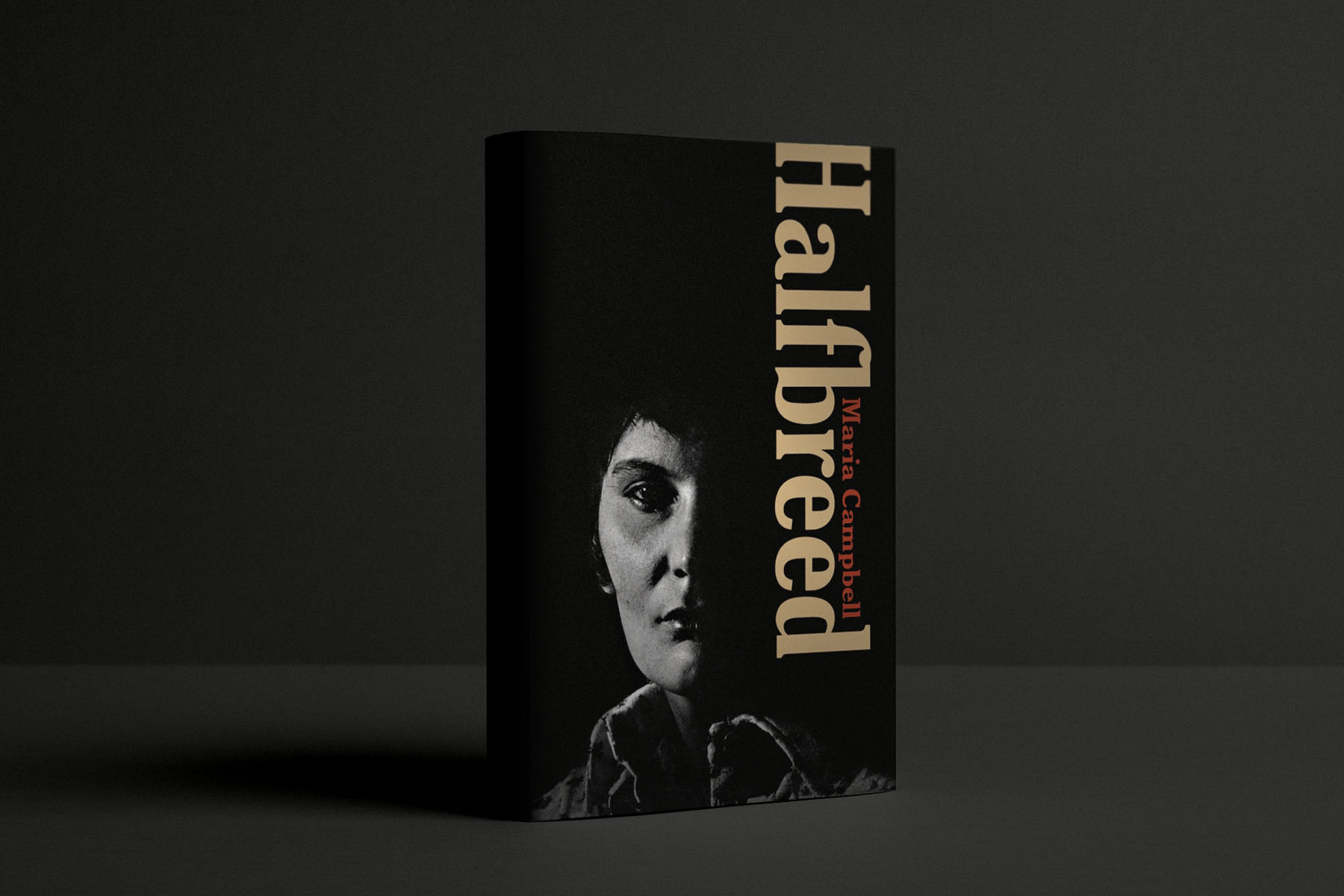

Halfbreed was an instant bestseller and turned Campbell, now eighty-four, into a literary celebrity. Fifty years later, the memoir remains as captivating and unforgettable as it was on publication. It helped that Campbell, then thirty-three, was stylish and striking; one profile, in the Province, described her as “an intense, intelligent, articulate champion of native rights and customs.” It added, “She’s quite a woman. Quite a lady.” (Campbell hated the iconic cover, a black-and-white portrait of her half-shadowed face, and described it as “a mouldy body slowly creeping out of a grave” to a McClelland & Stewart staffer, who acknowledged in a memo, “I must admit I agree with her.”) Many of the initial reviews, even positive ones, were tinged with condescension. The Ottawa Citizen wrote, “Maria’s storytelling methods are basic, unencumbered by attempts to copy conventional literary techniques.” But Campbell’s writing is beautiful, evocative, and controlled from the opening paragraphs, which mingle nostalgia and grief:

The house where I grew up is tumbled down and overgrown with brush. The pine tree beside the east window is dried and withered. Only the poplar trees and the slough behind the house are unchanged. There is a family of beavers still there, busy working and chattering just as on that morning, seventeen years ago, when I said good-bye to my father and left home.

Halfbreed begins with Campbell’s early life in Saskatchewan, where she grew up in a Métis settlement along a road allowance—a narrow strip of Crown land bordering the road, where the Métis, who were excluded from the treaty rights and land accorded to Status Indians, lived literally on the margins of society. (“As Daddy put it, ‘Not a pot to piss in or a window to throw it out,’” she wrote.) Still, her childhood seemed happy: her convent-educated mother filled the house with classics, and Campbell grew up with Longfellow and Dickens, staging Shakespeare productions in the Saskatchewan backwoods with her siblings and cousins. From her beloved great-grandmother, whom Campbell called Cheechum, niece to Métis leader Gabriel Dumont, she learned the history and stories of her people.

Though the book was a sensation, Campbell was frustrated by the reception, which tended to focus on the time she spent in Vancouver, where she turned to sex work for survival. “Nobody has understood what I tried to say in that book,” she told a journalist in 1973. “They’ve wanted to talk about drugs and prostitution, not about what it’s like to be a halfbreed.” The memoir, a searing indictment of colonialism, had been misread as an inspiring tale of one woman’s triumph over adversity. She turned down eager offers from producers who wanted to buy the movie rights, believing they were only interested in sensationalizing the darkest moments of her life. (Halfbreed is currently being adapted for the screen by Métis filmmaker Berkley Brady.)

McClelland & Stewart had encouraged Campbell to remove libellous details from the manuscript, including the names of public figures and politicians who had sought her services as a sex worker, but they made one significant change without her consent. In 2017, scholar Alix Shield, then a graduate student at Simon Fraser University, uncovered two pages the publisher had deleted that described how, at fourteen, Campbell was raped by an RCMP officer in her home.

Jack McClelland argued that although he was certain the rape “occurred just as I know it occurs today,” the description of it could lead to an injunction blocking the book’s distribution. The publisher had been willing to publish risky material on behalf of authors like William S. Burroughs, whose novel Naked Lunch was targeted by the Metropolitan Toronto police morality squad in 1963, and Leonard Cohen, whose Beautiful Losers was reviled as obscene by the public and critics upon its release in 1966. But he didn’t fight for Campbell. She was adamant that the passages be included, adding them back into the manuscript and obtaining her own lawyer, who disagreed with the legal counsel at McClelland & Stewart that they posed a risk to the distribution of the book.

In the end, they made the decision for her. Four months before the book’s release, Campbell’s editor, David Berry, wrote, “We made very few changes in the manuscript, and since there was a big rush to get it to the printer I didn’t think it would be worthwhile to send it back to you.” Only when her finished copy arrived did Campbell learn they had erased the record of her assault.

The year after the revelation was made public, McClelland & Stewart published a restored edition. The Saskatchewan RCMP issued a statement, as reported by the Saskatoon StarPhoenix, describing the incident as “highly concerning,” but added, “we are unable to determine if a complaint was ever filed or an investigation conducted at the time.” Campbell wrote that her grandmother, who found her after the assault, urged her not to tell her father: “If he knew, he would kill those Mounties for sure and be hung, and we would all be placed in an orphanage.” Her publishers, whether they admitted it or not, shared this instinct: the word of an Indigenous woman, even if a published author, counted for far less than that of a police officer.

Fifty years later, it’s this element of Campbell’s memoir that feels the most tragically relevant. Many Indigenous women have reported sexual assaults and violence at the hands of Canadian police officers. “Poor people, both white and Native, who are trapped within a certain kind of life, can never look to the business and political leaders of this country for help,” wrote Campbell. “Regardless of what they promise, they’ll never change things, because they are involved in and perpetuate in private the very things that they condemn in public.”

“I write this for all of you,” Campbell wrote in the introduction. “I want to tell you about the joys and sorrows, the oppressing poverty, the frustrations and the dreams.” Today, as when Campbell wrote Halfbreed, Indigenous nations are fighting for their rights and sovereignty, and the rich and growing body of Indigenous literature is both a tool for and reflection of those efforts. Campbell’s reflections on her Saskatchewan homelands, and the reverberating trauma of dispossession and displacement, are echoed in the works of many contemporary Indigenous authors who weave together the ideas of land, identity, and resistance: Billy-Ray Belcourt, Joshua Whitehead, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. In Halfbreed, Campbell sought to portray her people—their lands, their history, their struggles—in all their specificity. It’s an approach that remains as critical and revolutionary today as it was then—one that pushes back against vague and generalizing notions about Indigenous peoples that threaten to erase the distinct contours of our nations and identities.

What made Halfbreed so powerful, then and now, was not just that Campbell’s life held as much drama and tragedy as a Hollywood script. It was her unwavering clarity and knowledge of her own value: as a Halfbreed, as a woman, as a leader. Her generation was haunted by two defining tragedies for the Métis people: the defeat of the North-West Resistance and the confiscation of their land. “I only want to say: this is what it was like; this is what it is still like,” she wrote in the book. “I know poverty is not ours alone. Your people have had it too, but in those earlier days you at least had dreams, you had a tomorrow. My parents and I never shared any aspirations for a future.” And yet Campbell did imagine a future for herself and her people, and she wrote it into existence.

Correction, June 22, 2023: An earlier version of this article stated that Maria Campbell is eighty-three years old. In fact, she is eighty-four; according to her representatives, her father did not register her birth until she was a year old. The Walrus regrets the error.