Like most Canadians, I have mixed feelings about the United States. On the one hand, I admire what it has wrought. New York. Harvard. Richard Meier. Apple. Ella Fitzgerald. The New Yorker and the New York Times. Walt Whitman. Johns Hopkins. Mark Rothko. NASA. Charlie Rose. Cole Porter. The Smithsonian and MoMA. Robert Caro. Venice Beach. Francis Ford Coppola. New Orleans. Meryl Streep. Silicon Valley. Terry Gross. Knopf. Muhammad Ali. PBS and NPR. Bob Dylan. I could go on. But the country that spawned all this greatness has also produced Guantánamo Bay; Fox News; the National Rifle Association; Entertainment Tonight; the unnecessary, expensive, and futile wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; Charlie Sheen; Twitter; reality TV; soaring income inequality; the vacuous celebrity of Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian; the UFC and mixed martial arts; the moral bankruptcy of Wall Street; and, let’s not forget, Sarah Palin and Donald Trump.

What especially irritates Canadians (and others, I assume) is America’s jingoism: its widely held and frequently asserted belief that it is the greatest nation in the world. Setting aside the absurdity of such a claim—how, exactly, does one measure the greatness of one country against that of another?—there is abundant evidence to the contrary. In the first episode of Aaron Sorkin’s new HBO series, The Newsroom, broadcaster Will McAvoy sums it up nicely when, channelling Howard Beale in the 1976 film Network, he tells a group of starry-eyed college students, “We’re seventh in literacy. Twenty-seventh in math. Twenty-second in science. Forty-ninth in life expectancy. One hundred and seventy-eighth in infant mortality. Third in median household income. Number four in labour force and number four in exports. We lead the world in only three categories: number of incarcerated citizens per capita, number of adults who believe angels are real, and defence spending, where we spend more than the next twenty-six countries combined… ”

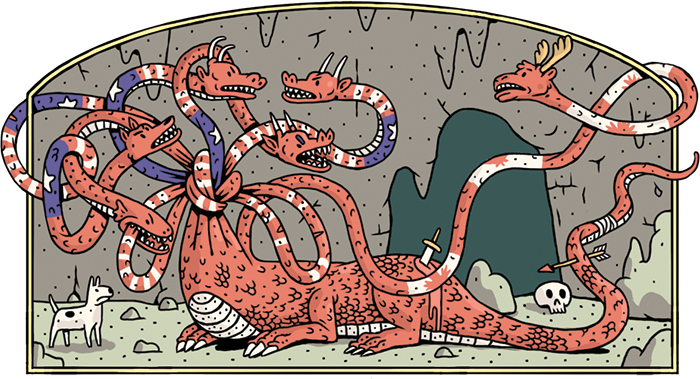

Some of McAvoy’s statistics may be questionable (The Newsroom is television drama, after all), but as American journalist Chris Hedges writes in this issue (“A Metaphor for America”), the larger point—that the US is in serious trouble—is now self-evident. No matter what the outcome of the November 6 election, the Republic faces enormous challenges: debilitating debt, a sputtering economy, crumbling twentieth-century infrastructure, some of the highest unemployment since the Depression, political stasis in Washington, DC, and , perhaps worst of all, an inability to forge a consensus on how to go about fixing any of it. As New York Times columnist Thomas L. Friedman has observed, “The arrow is pointing down in too many places.”

Twenty-five years ago, the question “What if America fails? ” would have seemed ludicrous. No more. But it’s the next question—“What happens to Canada if it does? ”—that should disturb our sleep, because if the United States can’t get the arrows pointing up, Canada will pay a price. Despite our best efforts to develop other international trade relationships, the US remains by far the largest purchaser of Canadian resources and manufactured goods. In 2011, it accounted for nearly 75 percent of our exports; the United Kingdom came in a distant second at 4.2 percent.

But trade is just part of the story. Although we complain about sharing the continent with the world’s largest economy (being the mouse that sleeps with the elephant, as Pierre Trudeau once put it), our proximity also confers on us huge and mostly unacknowledged benefits. It has made the best of America—the rich social, intellectual, and cultural harvest from its innovation, creativity, and ambition—more available to us than to any other country. We owe much of our success to the fact that we live in the right neighbourhood—or used to.

Perhaps, as many Americans believe, they can turn it around. Let’s hope so. But with skin in the game, we can’t be complacent. And neither should we gloat. The United States is not, as it insists, the only land of opportunity. Nor is it, as it also insists, uniquely virtuous among the nations of the world. The drumbeat of American exceptionalism, never louder than in an election year, is understandably galling. But if we are truly the kinder, gentler people we tell ourselves we are, our response to an America in extremis must be, if not a helping hand (what can we do, after all?), then at least compassion. There will be no shortage of schadenfreude elsewhere.

This appeared in the November 2012 issue.