I have lived in other Canadian cities—Montreal, Calgary, and Ottawa—but I have spent most of my life in Toronto. There is no place on earth to which I am more attached. Having lived at fourteen different addresses and gone to work at fourteen more, I know my way around. For fifteen years, I edited a magazine about the city, so I have a pretty good idea how it works and who makes it tick. Toronto is where I put down roots. My grandparents are buried here. My children were born here. This is where most of the people I care about—relatives, friends, colleagues—live and work. And it is where most of the big events in my life, happy and otherwise, have taken place. Not that it is the only city I care about. I love New York, Buenos Aires, London, Paris, Istanbul, and Hong Kong, although my favourite piece of urban real estate is Piazza del Campo, Siena’s main public square. But, for better or worse, Toronto is my home.

It could have been someplace else. Had I been offered the right job, I would have moved to New York; people often go where their work takes them. And sometimes they follow their hearts; my elder daughter lives in London, because she fell in love with an Englishman. But unlike my grandparents, who emigrated from the United Kingdom, I didn’t choose to make Toronto the centre of my universe. It just happened. And if it hadn’t, I would no doubt feel as connected to some other city as I do to the one from which I’m writing this. In this regard, I am not unlike a man in an arranged marriage who realizes after many years that he can’t imagine being with anyone else—not because she’s the most desirable woman in the world, because he knows she isn’t; and not because he could not have found happiness with another woman, because he knows he could have. The attachment he feels for her, he feels because she is the woman with whom he has lived his life.

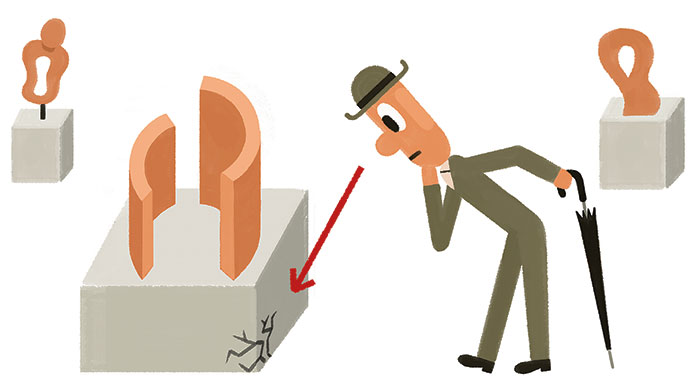

But you can care for a city without being blind to its shortcomings. Toronto has many admirable qualities, as John Lorinc acknowledges in the introduction to his article “How Toronto Lost Its Groove.” No city in the world has as successfully absorbed so many nationalities and religions. And it continues to be one of the safest big cities on the planet. But it is no longer the city Robert Fulford celebrated in his 1997 book, Accidental City, which argued that without meaning to Toronto had evolved into one of North America’s most livable urban environments. The intervening years have not been kind to Canada’s largest municipality, which now finds itself cash strapped, poorly governed, seriously congested, economically polarized, and generally falling apart. Toronto is a mess, but this is no accident. The city finds itself in this fix due to a litany of bad decisions by politicians, planners, and voters.

The election a year ago of a Tea Party–style mayor whose only campaign pledge was to cut spending and freeze taxes was the most recent such folly—and it can’t be undone for another three years, by which time the city could be in worse straits. In a democracy, the electorate is always right, even when it isn’t, but the election of Rob Ford begs the question: how could the voters of Toronto have been so irresponsible? No one wants to pay higher taxes, but even fiscal conservatives should ask whether the taxes we pay are sufficient to cover the costs of the services we demand, before voting for a politician who believes that the smaller the government the better. In fact, Toronto’s residential property taxes are lower than those in surrounding municipalities. The city’s problem is not that it is over-governed; it’s that it is badly governed. And the solution is not to spend less; it’s to spend more wisely.

Fixing Toronto should be a priority for both the premier of Ontario and the prime minister, but given the rest of the country’s ill will that’s about as likely as Conrad Black singing the praises of the American judicial system. So Torontonians will have to fix the city themselves, which means changing outdated attitudes toward municipal politics. We still call the federal and provincial governments “senior,” implying that municipal governments are “junior,” as indeed they were when the nation was founded in 1867. But today, when over 80 percent of Canadians live in cities and the country’s four largest cities generate 37 percent of the gross domestic product (Toronto alone accounts for 17 percent), these labels no longer seem appropriate and may even be dangerous. Because, as Toronto’s current predicament illustrates, we neglect municipal politics at our peril. It is time for the best and brightest Torontonians to wade into municipal politics, roll up their sleeves, and get to work. And it is time for all Torontonians to demand a better deal from the federal and provincial governments—not just for Toronto, but for all of Canada’s big cities. At stake is the country’s well-being, and its place in the world.

This appeared in the November 2011 issue.