Barack Obama’s efforts to reform American health care have rekindled the debate, here and in the United States, about the relative merits of our two systems. They are starkly different. Ours provides coverage to everyone, no matter what their financial circumstances, whereas in the United States only the elderly, children, the disabled, military personnel and their families, veterans, and the poor qualify for publicly funded care. Everyone else relies on health insurance, providing their employers offer it, or they can afford it themselves; unfortunately, this leaves 46 million Americans out in the cold. Our system is less expensive; we spend roughly 10 percent of our Gross Domestic Product on health care, the Americans more than 16. Is it any wonder medical bills are the leading cause of personal bankruptcy south of the border? Not that the Canadian system is without flaws, as Obama’s opponents have been only too willing to point out. The most obvious are excessive wait times; in Canada, as many of us know, it often takes longer than it should to see a specialist or get elective surgery.

Still, whatever its shortcomings, we seem to like our system more than they like theirs. According to recent Ipsos/McClatchy online polls, Canadians are more likely than Americans to say that they have access to all the health care services they need at costs they can afford, by a margin of 16 percent. The polls also found that among Americans who make less than $50,000 a year, only 37 percent say they have access to all the health care services they need; in Canada the figure was 61 percent. None of this is surprising. Since its conception in 1957, Canadians have embraced Medicare with an uncommon passion. Tommy Douglas, the premier who introduced universal hospital care in Saskatchewan ten years earlier, is even today a national hero. A few years ago, CBC broadcast a show called The Greatest Canadian in which Douglas emerged triumphant over Sir John A. Macdonald, Lester B. Pearson, Pierre Trudeau, Alexander Graham Bell, Sir Frederick Banting, and—God help us—Don Cherry.

In his 2004 book, The European Dream: How Europe’s Vision of the Future Is Quietly Eclipsing the American Dream, the American economist Jeremy Rifkin compared America’s predilection for individualism with Europe’s inclination toward collectivism. The European dream, he wrote, emphasizes “community relationships over individual autonomy, cultural diversity over assimilation, quality of life over the accumulation of wealth, sustainable development over unlimited material growth, deep play over unrelenting toil, universal human rights and the rights of nature over property rights, and global cooperation over the unilateral exercise of power.” Deep play aside, Canadians are clearly more European than American in these matters: we willingly contribute, through our taxes, to the support of everyone else. Pierre Trudeau called this the “Just Society”—pensions for the retired, financial aid for the disabled, welfare and subsidized housing for the poor, and, of course and above all, universal health care.

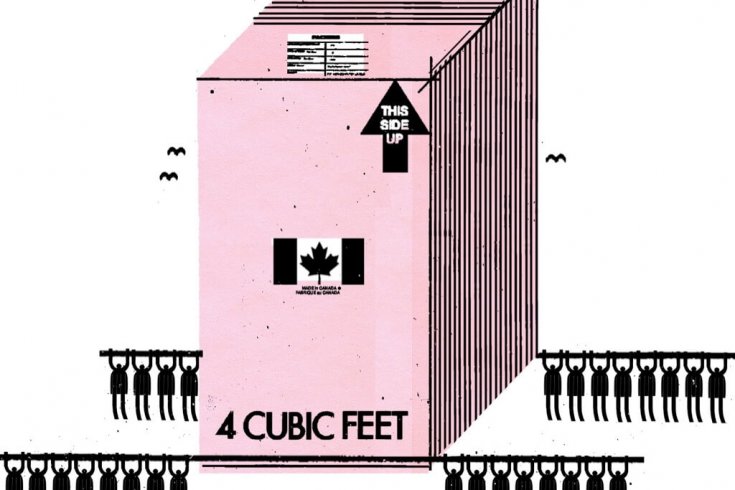

But at what cost? In a democratic society, the allocation of financial resources is always an issue, and because hardly anyone wants to pay higher taxes, it’s generally a zero sum game—a dollar can’t be in two places at once. This is the hard reality at the heart of Roger Martin’s essay in this issue (“Who Killed Canada’s Education Advantage”) about the unintended and harmful consequences of our obsessive attachment to public medicine. Martin is the dean of the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto; a graduate of the Harvard Business School; a co-founder of Monitor, a highly successful international consulting company; a director of Research in Motion and Thomson Reuters; and chair of the Ontario Task Force on Competitiveness, Productivity, and Economic Progress. He is a man drawn to the Big Picture, and what he sees when he looks at Canada today is, at least in one regard, troubling. In the last decade, expenditures on health care have beggared postsecondary education, putting the country’s prospects in today’s knowledge-based global economy at considerable risk.

Martin wants us to reconsider our priorities, and I can think of no better argument for his cause than the aforementioned Research in Motion, which Fortune magazine put at the top of this year’s list of the world’s 100 fastest growing companies. Just twenty-five years old, RIM has a rapidly expanding share of the world’s smartphone market, in excess of 12,000 employees, and a market capitalization of approximately $46 billion. Its headquarters are in Waterloo, an otherwise unremarkable Ontario community whose greatest asset is the math-centric University of Waterloo. Mike Lazaridis, the company’s founder and (with Jim Balsillie) co-chief executive officer, is a graduate—proof, if any were needed, that a society’s best investment in its future is in higher education, not artificial hips.