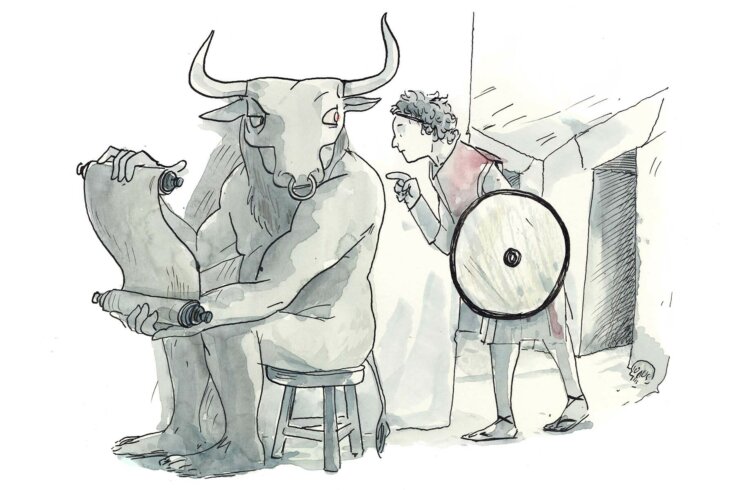

After slaying the Minotaur, a triumphant Theseus sailed back to Athens. To preserve the ship used by the legendary Greek king, Athenians removed its planks as they aged, “putting in new and stronger timber in their place,” writes Plutarch. The paradox—at least as philosophers mull it—is this: At what point does the ship become an entirely new object? If all the parts of Theseus’s ship are replaced, is it still the same vessel?

The Walrus has also undergone a process over the past two decades in which our parts have been incrementally switched out. Funding has changed; the office has relocated; the magazine has been redesigned several times, with new sections launched, old ones retired; we expanded online; we now manage fellowships, produce podcasts, run events; our roster of writers has been renewed; and, of course, our masthead has turned over. In January, we said goodbye to Editor-in-Chief Jessica Johnson, who left after six years with the organization. Hardly a single plank of the original ship is left. But here we are.

And where is that? What role do we play? Why read us? Believe me, we ask that question every day. We test ourselves against it at every story meeting. We describe ourselves as a home for fact-checked, long-form journalism. But surely no one subscribes to The Walrus solely because our facts are true or our features are long. Accuracy doesn’t replace editorial judgment; word count doesn’t confer importance.

Instead, readers have stayed loyal because, again and again, we break new ground in the country’s most pressing conversations. As of this issue, we begin the fifth month of our twentieth year—two decades since Marci McDonald, in October 2003, kicked off this entire project with a sprawling 11,000-word cover story on how Paul Martin’s business connections shaped his bona fides as the Liberals’ impending leader and soon-to-be prime minister. Martin went on to become PM, and The Walrus stayed true to its mandate to give ambitious and rigorous treatment to Canadian subjects in all realms. To nudge events out of newsprint into something stylish, long steeped, and definitive. The Walrus isn’t just a vehicle for great writing. If we cover something, we want you to give a damn about it.

The central question of Theseus’s paradox is what remains when everything changes. And that is what we are celebrating in 2023. Our survival in a challenging media landscape, yes, but also the survival of a specific idea about storytelling. Storytelling as an art and craft but also as something galvanized by a burning need to change, or challenge, some aspect of the world. In our cover story, “Where the Children Are Buried,” journalist Annie Hylton was invited by a First Nations community leader in rural Saskatchewan to observe a search for unmarked graves. It is a powerful and at times harrowing exploration of the meaning of “evidence” and the elusiveness of closure for so many communities who want to embark on these searches. It is also the kind of story The Walrus exists to tell—one that ChatGPT can’t come close to rivalling.