After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in 1945, the scientists behind the bomb decided to mark the dawn of the nuclear age with the creation of the Doomsday Clock.1 For the past seventy-five years, it has been set to alert humanity to how close we are to “midnight,” or total destruction, as a result of human-made technology. The clock has been moved twenty-four times over its history (backward eight times and forward sixteen), but with the war in Ukraine and the climate crisis, the annual assessment, released in January, now feels more relevant than ever. We asked Rachel Bronson, president and CEO of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists—a Chicago-based nonprofit that assesses global security issues—to unravel the science behind the clock.

When the clock debuted in 1947, it read seven minutes to midnight. In 2020, the time decreased to 100 seconds, where it remains today. How is the number calculated?

The clock first appeared on the cover of the bulletin’s magazine.2 In those early years, the time was set at the discretion of the editor and founder, Eugene Rabinowitch, who adjusted it based on his discussions with advisers in the field. After he died, in 1973, that responsibility moved to our Science and Security Board, which is made up of climate, nuclear, and tech experts.

The time isn’t determined by feeding data into computers and pumping out a number—though many of the scientists on the board are doing that regularly for their own work. Instead, it’s a judgment based on whether humanity is safer or at greater risk compared to prior years.

What factors are considered when making that decision?

In 1945, the only technology that had potential to change life on earth as we knew it was nuclear. There was great optimism around what it could do: power spaceships, provide sources of clean energy. But the risks were also very clear, so it became our focus.

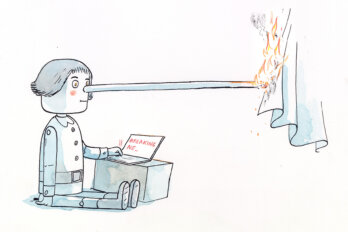

Over the years, other issues have become more relevant. Climate change isn’t something that we were formally focused on prior to 2007. We’re also keeping our eyes on emerging technologies and asking whether we’re managing them in ways that are advancing, instead of threatening, life. More recently, we’ve given attention to how mis- and disinformation is being used to undermine trust in institutions.

Are there notable examples of when the clock has moved backward or forward?

International arms control agreements and changes in military postures tend to move the clock backward. The most significant change was in 1991, after the Cold War, when there was a real commitment to reducing the number of nuclear weapons being created.

The year 2016 was another big one: there were big international agreements on the horizon, with the Iran nuclear deal and conventions in Paris around climate change. But then Donald Trump was elected president, and the United States pulled out of the Iran deal and the Paris Agreement. Instead of being able to move the clock back in 2017, we moved it forward.

In 2022, because of the war in Ukraine, there has been a lot of attention on us. We reserve the right to move the clock at any point but chose not to when the invasion first happened in February because we’d already factored the increasing tensions into our decision in 2021.

Anything else we can learn from the clock?

It’s intended to be a symbol3 to remind us that the fate of the world is in our hands. Ultimately, it’s up to us policy makers and civic organizations to demand that we better manage the risks that science and technology present so that we can reap all of their benefits.

1. Albert Einstein was among the Doomsday Clock project’s earliest contributors.

2. Martyl Langsdorf, the artist who created the original clock illustration, initially considered using the symbol for uranium on the cover of the magazine instead.

3. There is a physical Doomsday Clock, located at the University of Chicago, which is set each year to reflect the bulletin’s latest assessment.

As told to Alex Tesar. This interview has been edited from two conversations for length and clarity.