To mark the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act, The Walrus teamed up with Toronto Metropolitan University for a community storytelling project. Chinese Canadians from across the country submitted personal stories about their families and life in Canada. Project assistant Darya Soufian curated the submissions and collected these pieces of personal history:

Wendy Chin

“Wendy, you’re the only one I can talk to, because you have Chinese culture,” I remember my father-in-law, Chin Wing Git (Stanley Chin), saying to me one day. “My wife and my sons are born here; they’re so Canadianized and do not understand the heritage.” As someone who migrated from Hong Kong to Toronto relatively late in the twentieth century, in 1967, I was ignorant of the early Chinese immigrant experience. Fascinated by his stories, I urged him to tell me more, usually as we devoured duck wings and pig tongue, a dish the rest of the family did not care for.

My father-in-law, whom I call Dad, embarked on a solo voyage to Canada as a fifteen-year-old, in 1920, a time of political turbulence in China. He was to meet his father in Chicago, but that did not happen. He laboured in mining camps across Canada before landing up as a houseboy with a wealthy family in Toronto, where he learned English and the etiquette of Canadian life. Though the Chinese community of Toronto was small at the time, he found kinship with the “tongs”—fraternal associations of fellow countrymen. Time was spent playing mah-jong and longing for wives and a sense of belonging.

In 1943, Dad married Nellie Lee, a second-generation Chinese Canadian. She was nineteen, he was thirty-eight. During the Second World War, they ran a restaurant in Newmarket; Dad’s cooking skills were abysmal, but soldiers from the training camp nearby devoured chop suey while enthusiastically feeding coin after coin into machines at the restaurant. Cannily observing this, Dad moved the family to Toronto and ventured into the jukebox business. The boys helped after school. Father and sons drove a beat-up truck, collecting coins and servicing machines in restaurants and bars. They were so successful that a Chicago conglomerate tried to take over the business. The executives were astounded to meet their Canadian counterparts: a contingent of my father- and mother-in-law and their three young sons. Later, the family mounted a counter takeover and became the largest jukebox operator in the Toronto area in the 1960s and ’70s.

My father-in-law’s experience is the unsung chord of the Chinese Canadians’ immigration song—the beautifully played note and the silence living behind it.

Ging Wei Wong

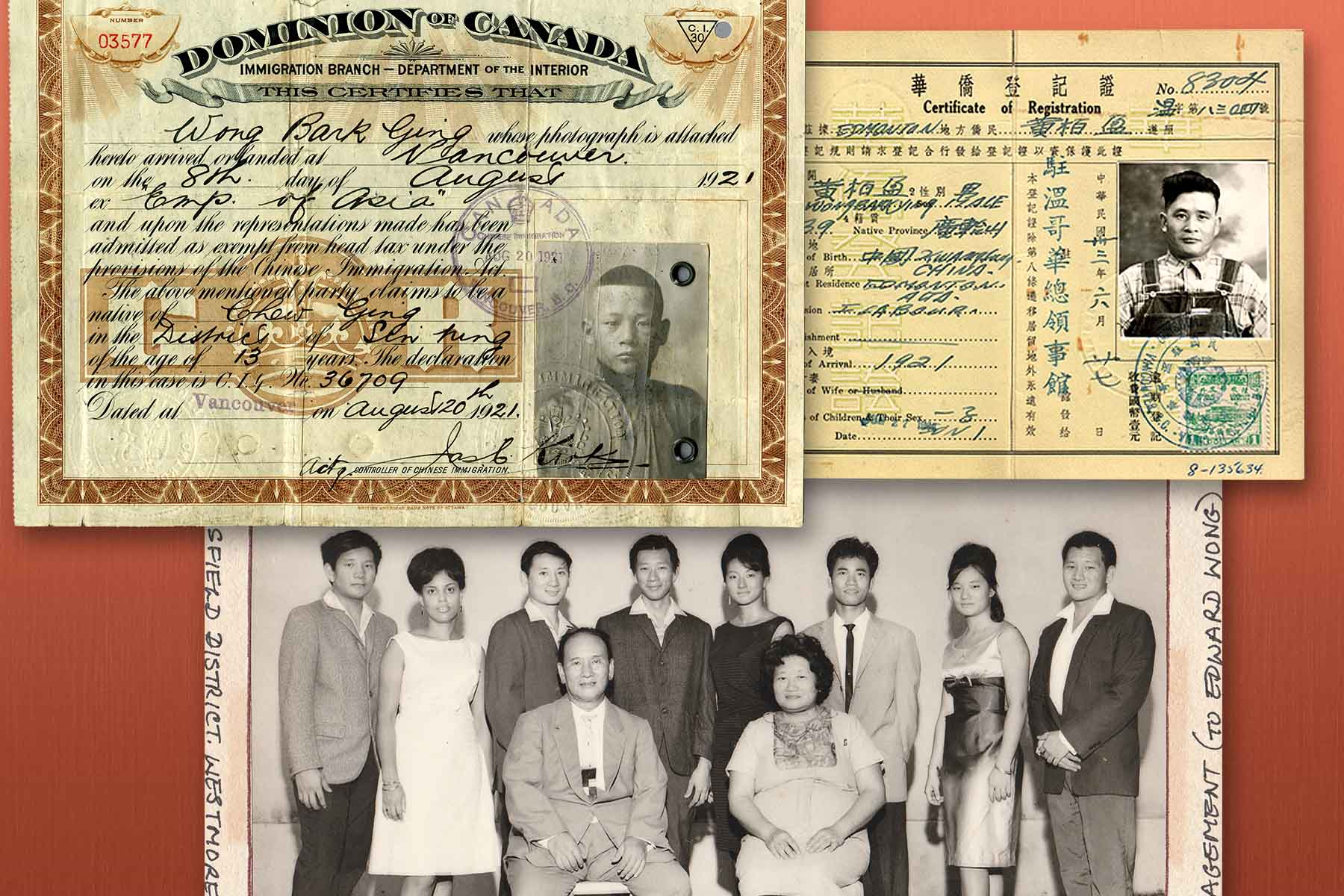

My father, Wong Bark Ging, was born in an impoverished village in the county of Taishan (known locally as Hoisan). Because he was the oldest son, he was chosen at age thirteen, in 1921, to go to “Gold Mountain,” also known as British Columbia.

He struck out on his own, and by 1924, he was in Alberta, working in mining camps, cookhouses, and farms. From Edmonton, he returned to his ancestral village in 1930 to marry Young See. Because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, he returned alone in May 1931. He became an independent market gardener along the fertile banks of the North Saskatchewan River, having learned about growing food when he lived in China.

The discriminatory act was finally repealed on May 14, 1947, making it possible for my father to obtain his Canadian citizenship. He applied for Young See to join him in Canada, and in 1949, eighteen and a half years after they were married, she did. In 1954, I came into the family.

Our main chore on our Namao farm was weeding, on our hands and knees, using old rusty knives. We harvested crops in September and October. We would spend a day processing a ton of cabbages regardless of the weather. I remember my father would tell us, “Get an education so you don’t have to work like a mule.”

Across the road was the market garden of Gee Cheung, whose son would occasionally come over to play. We spent many hours building a neat tree fort on our land and snacked on the wild Saskatoon berries that grew nearby. In our spare time, we’d explore the rural roads on our bicycles.

My parents retired after our farm was sold in 1975 and lived out their lives in north Edmonton. “I still like to visit the land where my father’s market gardens once stood; I feel a special bond there with him and the earth.”

Carol Williams-Wong

My husband and I were born during the 1940s and grew up in Jamaica. Our Hakka ancestors came to the Caribbean islands as indentured labourers in the 1800s.

We both received excellent education at our respective schools. We furthered our education in Canada and got married and were granted Canadian Landed Immigrant status.

In the early 1970s, my husband, my young son, and I returned to Jamaica and lived in Montego Bay. We had two more sons as our business thrived. In the late 1970s, socio-political events prompted many middle-class Jamaicans, including our family, friends, and relatives, to immigrate overseas, mainly to North America.

In 1979, a few years after settling in Ontario, we left for Hong Kong because my husband, who worked for an engineering company, was sent on an overseas assignment.

While living in Hong Kong, our family discovered the Hakka villages where our fathers had grown up and our cultural roots across the Hong Kong–China border in Guangdong province. While my husband gained engineering experience, I learned various ancient Chinese arts.

After his job contract expired in 1981, our family resettled near the historic Unionville part of Markham. Our sons were involved in charitable organizations and sports associations before leaving for the University of Waterloo.

I served as president of the local Unionville Tennis Club and became regional coordinator for the Ontario Tennis Association. I was involved with the flag-raising ceremony for Jamaica’s fiftieth anniversary of independence, in 2012, and became a member of the Markham Arts Council as well. And in 2013, I received the Mayor’s Seniors’ Hall of Fame Award for outstanding volunteerism and community service in the city of Markham.

In partnership with 100 YEARS LATER: The legacy of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Toronto Metropolitan University.