“Make it new,” urged the poet Ezra Pound early in the twentieth century. He wanted writers to abandon vague, overfamiliar modes of expression and to explore fresh territories of speech. Pound’s advice had a lasting influence on the language used by poets. Soon, the quest for the new became a dominant impulse in modernist literature, as it already was in painting, sculpture, and classical music. “The sentence should be arbitrary,” Gertrude Stein declared in How to Write. “A paragraph such as silly.” But readers were skeptical from the outset.

Most of us don’t seek out a new form of language, and if we happen to come across arbitrary sentences or silly paragraphs, we’re less than thrilled about it. The old idioms work just fine. We know what they mean. Even if I store food in cartons in the fridge, I don’t “keep all my eggs in one basket.” Even if you never cook for yourself, you sometimes “put it on the back burner.”

Does this mean that old idioms are inevitably clichéd?

Not in the least. What counts is not the age of an idiom but the context that surrounds it and the way it’s expressed. Compelling idioms have the power to keep language real. Any smart adaptation of a familiar expression can deliver a small jolt of surprise to readers or listeners. Warning against consumers-debt addiction in the Guardian in September 2017, Zoe Williams wrote, “We don’t need any ailing canaries to tell us there’s a gas leak: we need to start asking how to escape this mine.” By using the old image of a coal-mine canary in an article about the crushing weight of debt, Williams made her argument come alive.

It can be hard to figure out if an original perception lies buried under the greasy words. Sometimes, this is inadvertent. But, often, it’s deliberate. “In songwriting,” observes the Canadian singer-songwriter Blair Packham, “given the brevity of the medium—three minutes or so—you have to establish the setting or the premise of the song quickly. Sometimes, a well-placed cliché can help. And the very medium of pop music—of its time, meant to be of the moment—means, logically, that there is always a new audience coming along, unaware of clichéd words and phrases, willing to accept them at face value.”

For the powerful, the repetition of stock phrases can be a valuable tactic. These phrases serve to fortify rhetorical armour, deflecting all attack. The armour often brings clichés and abstract words together in a metallic professional embrace. Consider this, from an article on the website of the British government: “The Prime Minister emphasised her desire to listen to the views of businesses, to channel their experience and to share with them the government’s vision for a successful Brexit and a country in which growth and opportunity is shared by everyone across the whole of the UK.” Or this, from a speech by the CEO of Exxon Mobil: “Our job is to compete and succeed in any market, regardless of conditions or price. To do this, we must produce and deliver the highest-value products at the lowest possible cost through the most attractive channels in all operating environments.”

To quote neither the Bible nor William Shakespeare: yada yada yada.

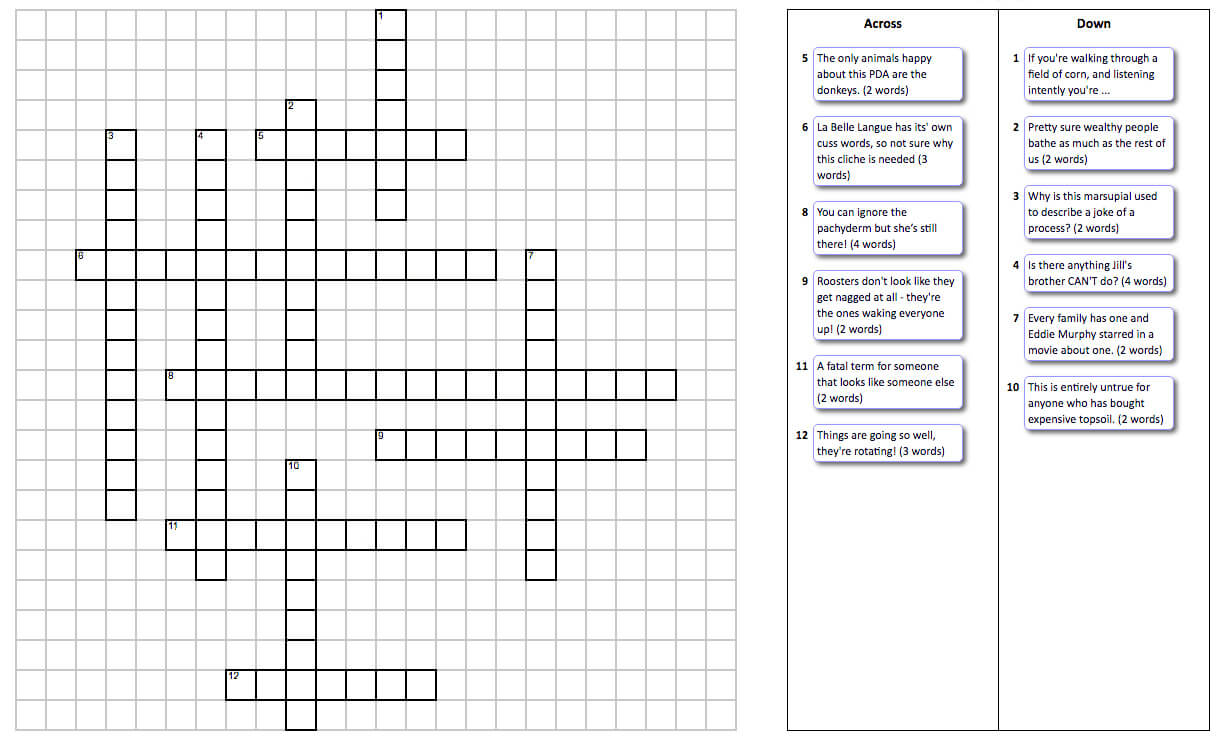

Crossword of Clichés

“The great enemy of clear language is insincerity,” George Orwell wrote in 1946. “When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns…to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish squirting out ink.” In his brilliant essay “Politics and the English Language,” Orwell gave some lively examples of what a “tired hack on the platform” was, in his time, likely to say: “bestial atrocities, iron heel, bloodstained tyranny, free peoples of the world, stand shoulder to shoulder.” A few of those expressions have become less prevalent over time, but others remain current. Presidents and prime ministers still boast about standing shoulder to shoulder, even while they knife each other in the back.

On July 1, 2017, the 150th anniversary of Canada’s birth as a nation, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau delivered an outdoor address before thousands of people on Parliament Hill, in Ottawa. The text of his speech was riddled with abstractions and clichés: “The story of Canada is really the story of ordinary people doing extraordinary things….Canadians know that better is always possible.…Our job now is to advance equal opportunity to ensure that each and every Canadian has a real and fair chance at success.” These are worthy sentiments. They’re also numbingly familiar—Trudeau’s language could have been lifted from a thousand other speeches, and probably was. As Orwell put it, “if you use ready-made phrases, you not only don’t have to hunt about for words; you also don’t have to bother with the rhythms of your sentences, since these phrases are generally so arranged as to be more or less euphonious.” Listeners can be lulled into smiling submission.

Or they can be roused to a condition of prefabricated outrage. Clichés help in that process too. A few weeks after Trudeau’s address, the governor of Texas, Greg Abbott, spoke at a sheriffs’ convention in a city named Grapevine. “Respect for our law enforcement officers must be restored in our nation,” he said. “The badge every sheriff and every officer wear [sic] over his or her heart is a reminder of a sacred trust, commitment, and contract with each of us. For law enforcement to stand in front of us and all that threatens, we must stand behind them. It is time for us to unite as Texans and as Americans and to say no more—no more will we tolerate disrespect for those who serve, and no more will we allow the evil merchants of hate tear us apart.” Abbott’s grammar was shaky, but the trajectory of his rhetoric was clear. His repeated use of “must,” combined with clichés like “evil merchants of hate,” allowed for no dissent. Standing at a podium in a business suit and tie, the governor bore a distinct resemblance to a cuttlefish squirting out ink.

An equally troubling type of political language is the “dog whistle”—an idiom born in the 1980s, although the practice it refers to is much older. The expression draws on the idea that dogs hear and respond to high-frequency noises beyond the reach of human ears. It means the use of coded messages to reach certain targeted groups, without the rest of the public being aware what’s going on. Those messages may rely on idioms. In 2016, Kellie Leitch, a candidate to lead Canada’s Conservative Party, surveyed potential supporters on whether immigrants should be screened for what she called “anti-Canadian values.” One of her rivals for the leadership, Michael Chong, denounced the idea as “dog-whistle politics.” The phrase “anti-Canadian values” told Conservative voters that Leitch would be the right leader to stop Muslim immigration, without the candidate needing to spell it out.

Dog-whistle expressions are an example of the unpleasant use idioms are sometimes put to. But, in a repressive society, words, images, and idioms can play a subversive role. China blocked all social-media references to Winnie the Pooh in 2017—the honey-loving bear had become an online euphemism for the country’s president, Xi Jinping, who is short and pudgy. When bloggers in China post an image of a river crab, they’re almost certainly referring to censorship. Why? Because “harmonized” and “river crab” are both hexie in Chinese—the words differ only in tone. And after the previous president, Hu Jintao, spoke repeatedly about promoting a harmonized society, “river crab” turned into a symbolic substitute for “censored.”

Sometimes the line between idiom and cliché gets blurred. On lists of clichés, I’ve found expressions like “cut off your nose to spite your face,” “a leopard cannot change its spots,” “wear your heart on your sleeve,” and “a few sandwiches short of a picnic.” But are these really clichés?

I don’t think so. If all those expressions were clichés, we could come under fire for speaking in any kind of figurative terms. The distinction between an idiom and a cliché is partly subjective, but it also depends on the rate and type of usage. For an idiom to be broadly understood, it needs to be occasionally heard or read. All four of those expressions would bemuse a newcomer to English. They make sense to us only because we’ve met them before.

We don’t want to run into them too often, though—repetition of any phrase can turn it into a cliché. Clichés are, by definition, recurrent: they encourage us to think and speak along predictable tracks. When the tracks turn into wheel ruts, it’s a challenge to steer out of them. We may find ourselves stuck in a verbal furrow, saying, “At the end of the day, let’s face the facts: I’m giving it 110 percent.” When people hear an expression like “drain the swamp” day after day, how long does it take before they begin to accept what the speaker means by those words? If idioms help us think outside the box, clichés box us in.

“The straw that breaks the camel’s back” is an expression that has worn out most of its welcome by overuse. It’s the winning variant, so to speak, from among a long list of similar idioms, the oldest of them being “the feather that breaks the horse’s back.” Over the centuries, other versions included “the straw that breaks the donkey’s back,” “the peppercorn that breaks the camel’s back,” and “the melon that breaks the monkey’s back” (this one made the most sense and, therefore, had little chance of success). In August 2017, a story on the CBC News website tried to twist the idiom into something fancier than a cliché by saying that the new government of British Columbia had decided to place “more regulatory and legal straws on the camel that is the Trans Mountain pipeline.” Sorry, but no matter how you look at it, a pipeline is not a camel.

Still, it’s possible to subvert a cliché if listeners are reminded of its literal meaning as well as its figurative sense. One routine expression for trouble is “in hot water.” When CNN asked the environmentalist Bill McKibben in 2017 about two new reports on the severity of climate change, he replied: “These studies are part of the emerging scientific understanding that we’re in even hotter water than we’d thought.” Perhaps McKibben was deploying a figure of speech in a clever way, drawing attention to the gravity of the issue by giving physical meaning to an old idiom. Or perhaps he was undermining his message by resorting to a cliché.

The idea of the cliché has now become pervasive far beyond its use in oral and written language. It proved so valuable there that it elbowed its way into other realms too. Russian villains and far-fetched car chases are said to be clichés in Hollywood movies. Appearances of the Russian villain may be accompanied in the soundtrack by a dark, brooding melody played in a minor key: a musical cliché. Scenes of cute girls and boys dispensing advice to their hapless parents have become a cliché in TV advertising. These examples are, if you like, nonverbal idioms, all of them predictable in their tone and implications, all of them beset by overuse.

In some contexts, alas, the use of clichés is the rule, not the exception. If you’ve ever listened to an interview with an NHL star, you’ll know what I mean. The Stanley Cup–winning goal in 2014 was scored in double overtime by Los Angeles Kings defenceman Alec Martinez, and following the game, Martinez was asked how the Kings had reacted after falling behind their opponents late in the second period. “We just did it by committee,” he said. “We’ve got great leadership in our locker room, and, you know, we’ve been in that situation before. Obviously, it’s not the situation you want going into the locker room after the second, but we came out and battled back.”

A few minutes after the most thrilling moment of his career, if not his life, Martinez was still talking in dull stock phrases: “by committee,” “leadership in our locker room,” “been in that situation,” “obviously…came out and battled back.” Sad to say, the avoidance of personal language has become part of the culture of most professional sports. Yogi Berra, a longtime catcher for the New York Yankees, had a unique style of speaking that was memorable not just because he made some hilarious mistakes (“pair up in threes,” for instance) but because he spoke candidly and personally (“we were overwhelming underdogs”). Berra had a rare gift for turning clichés back into idioms.

Clichés are prominent in the stories that athletes repeat to outsiders. Unlike abstract words, they also appear in some of the stories we tell about ourselves (mission statements are full of them). But, to quote a proverb at least four centuries old, “one man’s meat is another man’s poison.” What you deplore as a cliché, I may cherish as a soul-stirring idiom. In his 2008 election campaign, Barack Obama’s defining slogan was “yes, we can!” A cliché, some voters felt. Eight years later, Donald Trump’s defining slogan was “make America great again!”

Was this an inspirational appeal or a dangerous cliché? The answer depends not only on the words themselves but on your own beliefs.

Idioms are like repeated musical phrases. Good writers know how to use them in harmony with the other elements of a text. This analogy helps us to see why clichés are so annoying. A cliché is like an earworm—a tune that plays endlessly inside your head, refusing to leave you in peace. In a literal sense, clichés are monotonous: they have a single tone. They make the same point over and over.

Idioms, by contrast, lend themselves to a variety of tones. The verbal melodies they express may appear in unpredictable form. They are perpetually ready to shift shape. By uniting a physical image with an abstract thought, idioms can take their place in many different patterns. When you utter an expression that has startling idiomatic force, it can make your listeners or readers hear or see the world in a novel way.

Watch Your Tongue: What Our Everyday Sayings and Idioms Figuratively Mean by Mark Abley. Copyright © 2018 by Mark Abley. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster Canada, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.