Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

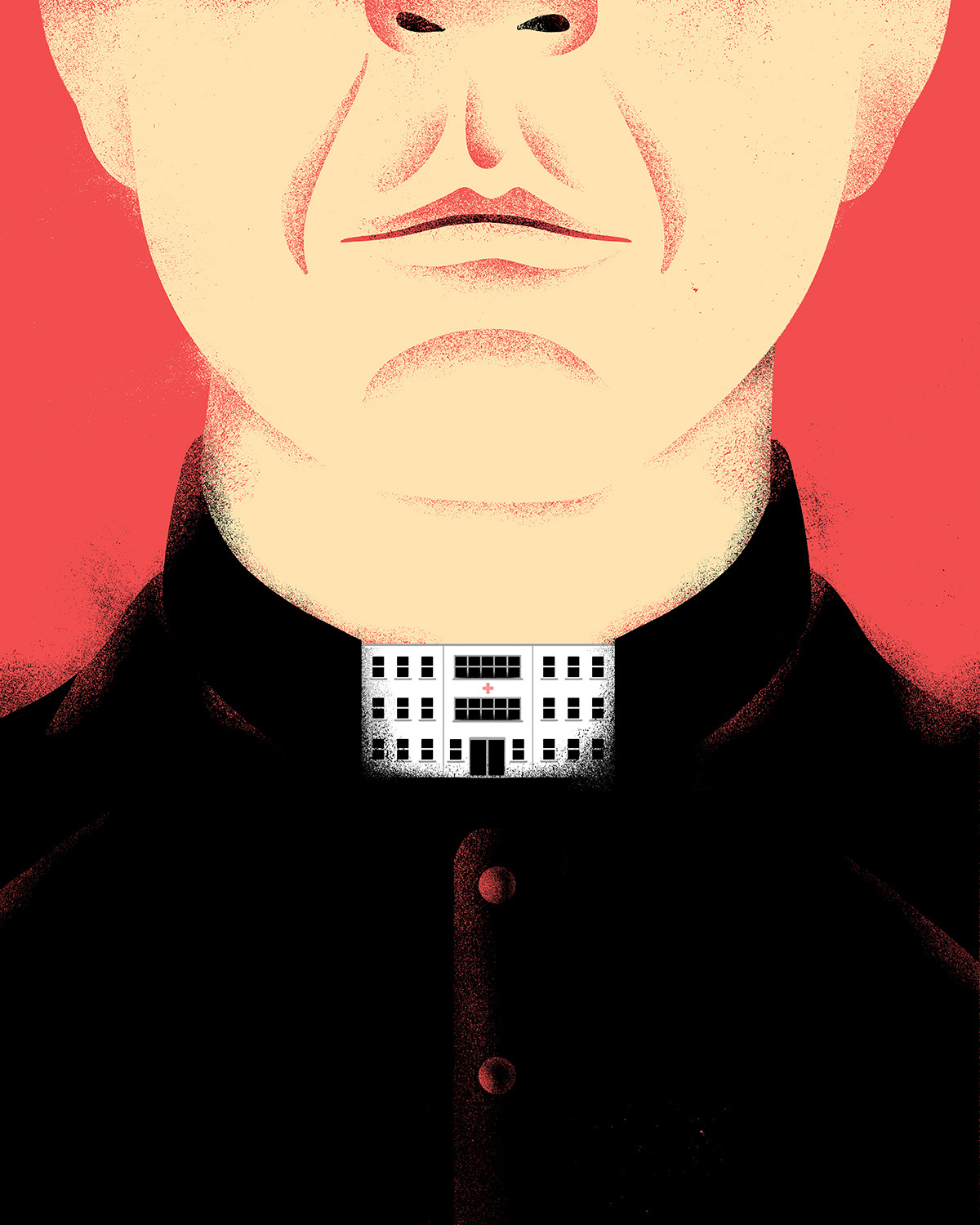

In the fall of 2020, Susan Camm was among a small group of employees touring a brand new seventeen-storey tower at St. Michael’s Hospital, in downtown Toronto. She liked the large single-patient rooms—a hallmark of modern hospital design—and the big windows that filled the space with sunshine. But something caught her eye: a brass crucifix on the wall. “I had an almost visceral reaction,” she recalls.

Camm, who was then a clinical manager at the hospital, had come across crucifixes at St. Michael’s before. But most had been taken down over the years. What shocked her is that the Christian symbols were in brand new rooms. This wasn’t a decision someone had made decades ago; it was one made in 2020. Later, when she had the chance to enter a patient room alone, she dragged a stool over to the crucifix, stood up, and tried to pull the figure off the wall. Unlike the ones in older rooms, it wasn’t simply hanging on a nail. She would have needed a chisel to pry it off.

While the crucifix is a familiar symbol for Christians, it can be a discomforting one for other patients. Camm imagined a residential school survivor waking up in the hospital after a procedure—confused, disoriented, vulnerable—and seeing the emblem of an organization that protected their abusers. Plus, Camm argues, it’s disrespectful to the tens of thousands of patients from Toronto’s diverse neighbourhoods, many of whom are not Christian, who receive care at the hospital each year. But Catholic symbolism and doctrine—governing reproductive health, fertility treatments, care for LGBTQ2+ patients, and medically assisted death (MAID)—is part of 129 health care facilities across the country. In Alberta, Catholic facilities currently maintain 12 percent of acute-care beds and 27 percent of palliative-care beds. And, in Ontario, Catholic institutions control around 15 percent of health services. In some parts of Canada, such as Antigonish, Nova Scotia, and Gravelbourg, Saskatchewan, the only hospitals in town abide by Catholic ethics.

When patients want an abortion or their tubes tied, they might be told, “Sorry, we don’t do that here.”

Much like how Catholic schools are funded by tax dollars, Catholic hospitals are part of this country’s universal health care system. Before the institution of public health care, in the 1950s and ’60s, the land and buildings for Catholic facilities might have been paid for by religious orders. Today, however, the hospitals are funded the same way as non-Catholic ones. Provincial and territorial governments cover their operating budgets, including staff, equipment, and energy bills. And the hospitals raise money for extras, like fancy new wings and upgraded machines. (Catholic hospitals and secular ones are governed by the same provincial legislation, which outlines their reporting requirements, employment standards, and more. These laws permit faith-based hospitals to refuse some services for religious reasons.) But, unlike those who attend Catholic schools, which their parents might choose for faith-based education, patients often end up in a Catholic health care facility simply because it’s the closest one. Many Canadians don’t even realize which hospitals are Catholic and which are not, and many patients are never affected by their hospital’s religious affiliation. For a patient who visits St. Michael’s, in Toronto, or St. Paul’s Hospital, in Vancouver, for an MRI or an appendectomy, the experience would be the same as at any other publicly funded hospital. It’s when patients request an abortion or are hoping to have their tubes tied that they might be told, “Sorry, we don’t do that here.”

In these cases, patients are often redirected or transferred to other facilities, which can increase the wait time for the procedure they’re looking to get and can be uncomfortable and painful for those who are sick. Patients often don’t know that they were denied care because of restrictions outlined in a 119-page Health Ethics Guide, which limits the kinds of procedure and treatment that can be performed at Catholic-run facilities. But health care workers see again and again how these rules affect patients. And a growing number of them, including Camm, are asking: In a country that boasts universal access to health care, why should publicly funded hospitals get to limit access on religious grounds? They’re also raising these concerns in a society that’s far less religious, and much more supportive of reproductive health care and assisted death, than it was decades ago. The number of Canadians who identify as having a religious affiliation has fallen from 90 percent in 1985 to 68 percent in 2019. The percentage of Canadians who identify as Catholic has dropped from almost half, in the 1970s, to 29 percent today. Almost 80 percent of Canadians support access to abortion, and almost 90 percent support medical assistance in death.

While reporting this story, I spoke with more than thirty health care workers who currently work or have treated patients at Catholic hospitals. Some highlighted that Catholic hospitals do plenty of good work stemming from their long history of serving marginalized urban populations. For example, Andreas Laupacis, current deputy editor of the Canadian Medical Association Journal, worked as a palliative care doctor at St. Michael’s for eight years. (Laupacis is also a former editor at Healthy Debate, where I worked with him.) When I asked him what he thought of the restrictions, he said, “Would I have liked for St. Michael’s to provide MAID? Yes.” But he also thinks it’s “not a coincidence” that St. Michael’s and St. Paul’s, both internationally renowned for their care of people struggling with addictions and homelessness, are Catholic. St. Paul’s took in HIV patients other Vancouver hospitals turned away in the early 1990s, and today the hospital is a global leader in treating HIV and infections related to substance use. In 1998, St. Michael’s was the first hospital in Canada to launch a research program dedicated to studying the intersection of health and inequities. Today, its Centre for Urban Health Solutions is piloting programs that aim to permanently house people, reduce COVID-19 exposure in shelters, and more.

But others I spoke to said tensions between the organizations and their employees play out every day, with staff and doctors finding creative ways to skirt the rules. Many expressed great frustration at risking reprimand or, worse, not being able to provide the care their patients need. Some gave the following examples, all of which occurred in the past few years, though they didn’t want their names attached for fear of reprisal. At St. Paul’s, a nurse called up a nearby clinic to see if they could sneak an injectable contraceptive medication to a high-risk patient. At St. Michael’s, a family doctor recorded a prescription for the abortion pill on paper, rather than in the patient’s digital chart, to avoid detection by the administration. And, in a Canadian town, a doctor told her patient that, if anyone asks why they’re getting their tubes tied, they should say it’s to reduce their risk of ovarian cancer, not to avoid pregnancy. “Okay, that’s weird, but no problem,” the doctor recalls the patient responding.

In 2021, after the news of mass graves of Indigenous children at Catholic-run residential schools, health care workers asked why governments continue to fund hospitals operated by the same religious institution. This is one of several factors behind the growing frustration among staff and doctors. Many of those raising questions are women, who have a much larger presence in medicine today than they’ve had in the past. On average, more women than men enter medical school each year, and that trend has continued since the 1990s. (Restrictions at Catholic hospitals disproportionately affect uterine health because they affect contraception, miscarriage, and abortion care.) The legalization of MAID has added to the discontent. Since 2016, health workers have had to transfer patients out of their Catholic-run long-term care homes, hospices, and hospitals, to be painfully jostled around in ambulances, simply to access the assisted death they want. Against this backdrop is a growing recognition among doctors that advocacy for their patients, and for the health of Canadians in general, is a part of their role.

“It’s incredibly anachronistic that, at a number of our facilities, the ultimate authority is appointed by the Catholic Church, literally by the Vatican,” says Ryan Hoskins, an emergency physician in BC who has written about Catholic health care in Alberta. “I think that’s absurd.” Michelle Cohen, a family physician in Brighton, Ontario, points out that Catholic hospitals can be a barrier for remote and rural Canadians especially. “If we have a single-tier system, where we are all supposed to be accessing the same level of health care, why is there a difference depending on which hospital you go to?” Romy Nitsch, an assistant professor of obstetrics at Queen’s University, reports that many in her specialty are concerned about Catholic hospital restrictions. “Women have the freedom of choice to make reproductive choices. And the institutions that prohibit it are publicly funded,” she says. “It’s a type of discrimination.”

In fall 2021, several doctors at St. Joseph’s Health Centre, in Toronto, demanded that their hospital stock emergency contraception. In January, Unity Health, the network of Catholic hospitals that includes St. Joseph’s and St. Michael’s, changed its policy in response to their request. In September 2020, a resident doctor in Kingston, Ontario, wrote to Frédérique Chabot, the director of health promotion at Action Canada, an organization that advocates for sexual health. The doctor explained that restrictions at the city’s Catholic hospital “resulted in longer wait times for procedures relating to women’s health”; the email ended with, “I’m asking for your help in figuring out how we can fight this.” Some are challenging policies around abortion too. Janine Farrell, a former resident of the family health clinic at St. Joseph’s, devoted her research, which she presented to her colleagues in fall 2021, to improving abortion counselling and referrals at Catholic hospitals. The previous year, when Farrell talked with an ethicist at Unity Health, she felt he tried to dissuade her from working on the project. “You know you’re coming up against a hundred years of history here, right?” she recalls him saying.

The history of Catholic health care for underserved populations—with strings attached—is a long one. Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, the first permanent hospital in what would later be known as Canada, was founded by Augustinian nuns in 1637. Over the next three centuries, Catholic congregations opened hundreds of hospitals across the country. The nuns cared for patients with smallpox, tuberculosis, and Spanish influenza. They cleaned wounds, applied oatmeal poultices, and brought bone broth to lips. They also prayed at bedsides often: patients confined to bed were more receptive to conversion, especially when the proselytizers were their caregivers. “Given that proselytizing and conversion were at the core of the mission of church-run hospitals,” writes Samir Shaheen-Hussain, a pediatric emergency doctor in Montreal and the author of Fighting for a Hand to Hold: Confronting Medical Colonialism against Indigenous Children in Canada, “they played an important role in the assimilation and elimination—in other words, genocide—of Indigenous peoples.”

At times, the Catholic Church ran hospitals and schools on the same compound. “Most of the patients were kids who were made ill in residential schools,” says Maureen Lux, a historian of medicine and Indigenous–government relations at Brock University. Protestant sects also opened hospitals and residential schools that targeted Indigenous communities and dominated the competition for religious reach in some areas of the country. But Catholics had a head start and a major advantage, Lux says. “The Catholics were always much more successful because they had employees who took vows of poverty. How much more could you want out of an employee that settles for room and board?”

As more European settler towns sprang up and cities grew, Catholic hospitals followed. The nuns treated soldiers, labourers, the elderly, and the poor, with doctors at times complaining that the nuns admitted people who couldn’t pay. (Protestant-funded hospitals generally operated more as businesses, with non-clergy managers. The first stages of universal health care didn’t arrive until 1957.) Catholic hospitals were also welcoming places for Irish Catholics, who, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, faced discrimination from Protestants. Still, in some places, like Winnipeg and Vancouver in the early 1900s, Catholic hospitals relegated Indigenous, Chinese, and Japanese patients to a separate wing or building with subpar care, very much in keeping with the wider racist health care practices of the time.

In 1942, representatives of more than 200 Catholic hospitals—a third of Canada’s hospitals at the time—formed what is now called the Catholic Health Alliance of Canada (CHAC). (Given their more prominent role in health care, it was only leaders of Catholic hospitals, not those of Jewish, Protestant, or other religious hospitals, who banded together nationwide to lobby for their institutions.) Post-medicare, the CHAC worked to protect Catholic-run hospitals from the threat of government takeover and to influence legislation around health care policy and funding. One of the CHAC’s biggest preoccupations was retaining Quebec members, who were unhappy with English Canada’s control over the organization, as chronicled by André Cellard and Gérald Pelletier in Faithful to the Mission: Fifty Years with the Catholic Health Association of Canada. But those efforts would ultimately prove futile when Quebec took over Catholic hospitals in the ’60s and ’70s—Quiet Revolution years that saw popular reforms of secularization and expanded social services. Today, Quebec and PEI are the only provinces without Catholic Church-run hospitals or long-term care homes. (While Quebec does have hospitals that carry religious names and imagery, the facilities are government run.)

Catholic health care in other provinces has also seen massive cutbacks. Catholic health care has gone from representing 35 percent of all health care in 1968 to just over 5 percent today, according to research by Hoskins. Governments saw the inefficiencies in funding both a secular and a religious hospital in many communities and chose to shut down some Catholic hospitals to ensure access to reproductive care. Sometimes, health workers themselves were the impetus behind the defunding of Catholic health institutions. In 2007, in Humboldt, Saskatchewan, two doctors resigned over their hospital’s refusal to perform tubal ligations (tying the fallopian tubes to prevent pregnancy), sparking a public debate about the Catholic nature of the hospital. The local health authority then surveyed community members, and almost 70 percent called for the authority to take over the hospital’s operation, which it did. Similarly, in 2017, Jonathan Reggler, a family physician and MAID advocate in BC, mobilized eighty other physicians to sign an open letter demanding that new provincial funding for hospices go to a secular institution; the local health authority agreed and also moved the existing hospice beds out of the Catholic facility and into the secular one.

The CHAC published its first ethics guide in 1970 and has updated it two times since. The most recent edition, based on input from dozens of Catholic clergy and scholars, was published in 2012 and remains in force. It includes thoughtful language about informed consent and supporting the whole patient. “Catholic health and social service organizations will care for all, regardless of religion, socioeconomic status or culture,” it reads. It also details numerous prohibitions that, ultimately, discriminate. On contraception: “The use of procedures or drugs deliberately and intentionally to deprive the marital act of its procreative potential, whether temporarily or permanently, is morally unacceptable,” it reads. On sexual orientation: “The primary and most intimate human relationship instituted by the Creator is that embodied in the marriage of man and woman. . . . Nevertheless Catholic health care seeks to demonstrate loving compassion, tolerance and sensitivity to those who disagree with or are unable to live up to these challenging teachings.”

Following it to a T could result in discipline, at least from Ontario’s provincial regulatory college, which requires conscientiously objecting doctors to refer patients. For instance, the guide states that “surgical interventions, hormonal therapy and referrals for sexual reassignment are inconsistent with Catholic teaching regarding the principles of totality and integrity and thus should not be performed in Catholic facilities.” Instead, people with “gender identification difficulties”—the words trans or transgender don’t exist in the guide—are to be “treated with compassionate pastoral care.”

When I asked a dozen Catholic health organizations in Canada about their restrictions, seven responded, including major ones like Covenant Health, Providence Health Care, and Unity Health. It became clear that they have implemented the guide similarly across the country. In fact, three of the responses contained several verbatim lines that couldn’t have been coincidental. The hospitals permit health care providers to prescribe hormonal birth control and medication for transgender patients so long as patients fill their prescriptions off-site—several Catholic hospitals explained that they don’t interfere in the confidential doctor-patient relationship. But the rules become stricter when it comes to what happens within the hospital’s walls.

Contraceptive medication and procedures are a major point of tension between health workers and Catholic institutions. For the most part, contraceptive medication is not available for in-patients through Catholic hospital pharmacies unless required for a noncontraceptive reason. And IUDs and contraceptive surgeries are also allowed only for broader health reasons, such as if the procedure could prevent heavy bleeding or avoid a high-risk pregnancy after a C-section, though the latter would be approved on a case-by-case basis. Health care providers told me that contraceptive gatekeeping most seriously affects patients who engage in survival sex (trading sex for food, protection, drugs, shelter, or other basic needs) and access health care only in crisis situations.

Leaving aside the reproductive-rights infringement, the idea that contraceptive procedures are medically necessary for some but not others is “a logical fallacy,” says Dustin Costescu, a family-planning specialist and OB-GYN at Hamilton Health Sciences. Unintended pregnancy is always riskier to one’s health than contraception, so all forms of contraception, including surgeries, should be granted on health grounds, he says.

The restrictions on contraceptive care are especially troubling when it comes to sexual assault. Many Catholic hospitals don’t stock emergency contraception for sexual assault survivors. They either send patients to another facility or call external sexual-assault nurses to visit and administer Plan B. Both workarounds take time and create gaps patients can fall through. For example, sometimes assault survivors decline the examination from a sexual-assault nurse, so they leave without getting emergency contraception.

One survivor of sexual assault told me that, even when the sexual-assault nurse did come to the St. Michael’s emergency department, where she was treated last winter, she didn’t get Plan B. A university student whose name has been withheld at her request, she said she waited ten hours before the sexual-assault nurse from Women’s College Hospital arrived. That’s when the nurse said she couldn’t offer her Plan B because it went against Catholic hospital rules. Both the nurse and the emergency doctor were apologetic and seemed frustrated by the situation, she recalls. Upon finally leaving the hospital, she bought the contraception at the pharmacy herself. (If she had been treated at another downtown emergency department, the drug would have been available in the hospital pharmacy, free of charge.) “The longer you wait, the less it works,” she says. “It doesn’t seem fair for survivors to have to go through sexual assault and then pay the $50 or whatever at Shoppers.” Both Unity Health and Women’s College Hospital say this should not have happened: the agreement with visiting nurses allows them to bring and administer the medication, the hospitals say. Hayley Mick, a spokesperson for Unity Health, called the situation “very concerning.” Later, she told me that the hospital now stocks the drug in its emergency departments and allows health workers to administer it for patients who have been sexually assaulted—a change that doctors at Unity Health had called for.

Kari Sampsel, medical director of the Ottawa Hospital Sexual Assault and Partner Abuse Care Program, says she is most concerned by the practice of some Catholic hospitals sending patients elsewhere to access emergency contraception. “For somebody to say those words out loud, ‘I have been assaulted—I need help,’ is a massive deal. And then to be told, ‘I’m sorry, we can’t help you here,’ no matter how nicely and caring you do it, it doesn’t engender that feeling of, ‘Okay, I’m in safe hands here,’” Sampsel says.

The refusal of Catholic institutions to perform contraceptive surgeries except in rare circumstances also means that patients have to travel farther and wait longer for care. This is the case in Kingston, where one of the two hospitals is Catholic. Doctors told me that, when Kingston Health Sciences was overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients, women were being directed to Napanee, more than a half-hour drive away, for reproductive surgeries. In some cases, these patients waited many months longer than they would have if Kingston’s Hotel Dieu Hospital had allowed the procedures.

Catholic hospitals are most consistent about their abortion policies. They don’t allow elective abortions or even abortion-pill prescriptions that patients can fill off-site. But they will allow medically necessary terminations if a woman could die or suffer harm in the time it would take to transfer her elsewhere. Health workers can make this call if a woman is in imminent danger, but if not, they’re expected to seek approval from the hospital ethicist and, sometimes, the local priest.

There have been close calls where patients’ lives were at stake. A resident at St. Paul’s said a doctor didn’t perform a dilation and curettage (D&C) to remove a deceased fetus for six hours even though the retained tissue had become infected and the patient was septic. The doctor was worried about running afoul of the hospital’s Catholic ethicists and thought they had to wait for a radiologist to confirm the obvious: no fetal heartbeat. “Had it been in any [non-Catholic] institution, it would have been a no brainer. They would have done the D&C right away,” says the resident.

Patients can also receive poor care when they show up to Catholic hospitals after abortions performed elsewhere. Ken Hahlweg, a family physician and abortion provider in Manitoba, has heard from patients with post-abortion complications who have been treated harshly at St. Boniface Hospital, in Winnipeg. “Health workers basically say, ‘Why would you even come here?’” he says. He’s clear that the judgment “comes from individuals,” but, he says, “people become all of a sudden brave when they’re within an organization that supports discrimination.”

Many health care providers argue that the patients most egregiously harmed by restrictions at Catholic hospitals are those who want medical assistance in dying. Catholic hospitals in Canada don’t allow the procedure, and usually these patients can’t simply get up and take a cab to the next hospital. Lisa Saffarek, who works as a health system administrator in BC, says her dad’s last two weeks were consumed by the logistics of trying to get a transfer out of a Catholic hospital for the assisted death that he wanted. In the end, he did get transferred to another hospital, but he died the morning after the transfer. It wasn’t the death he wanted, surrounded by his whole family. Saffarek describes her dad as a grab-life-by-the-horns guy who came to Canada from Germany as a teenage prisoner of war and went on to open a ski hill in Smithers. (Before he had the funds to buy a chairlift, he would teach people to ski by “walking up and down the slopes all day,” she says.) Saffarek says her dad wanted to talk to the nurses about MAID and how his decision was affecting his family, but “you could see them avoiding eye contact.” This lack of emotional support “was the hardest part,” she says.

Jonathan Reggler, the family doctor from BC, says he’s witnessed several patients suffer due to Catholic health institutions’ refusals to provide MAID. One patient had to be transferred by ambulance to the trailer he lived in, accessible only by an extremely rough gravel road. “We couldn’t give him the sorts of drugs that you would ordinarily give somebody for a painful transfer because he had to have capacity at the time of his MAID,” recalls Reggler. His trailer was too small, so Reggler administered MAID “in a cold, leaky vehicle shed.” One family doctor in Thunder Bay describes witnessing a patient being transferred from her room in a Catholic-run long-term care home, filled with quilts she’d sewn and photos of loved ones, to a sterile hospital room for MAID. In winter, she says, residents are transferred by ambulance when it’s minus-forty degrees out, simply to die. The patients are “disgusted,” the doctor says, “but this population is too weak and too frail and exhausted” to put up a fight.

Many legal experts believe the restrictions in the ethics guide would not withstand a Charter challenge.

Catholic hospitals don’t want to talk about the restrictions. They’re not typically shared in formal staff orientations. Instead, they’re passed down informally, from supervisor to trainee, often with eye rolls and shrugs. When I asked about the restrictions, a spokesperson from Covenant Health, a Catholic health care provider in Alberta, sent a multi-paragraph statement that doesn’t mention religion once. “Not all services are provided at every health facility. . . . For example in Edmonton, Alberta Health Services (AHS) transfers patients to Covenant for vascular surgery.” Catholic health organizations also don’t want to talk about the fact that patients could be harmed by the refusals. John Ruetz, president and CEO of the CHAC, wrote in an email that “the Health Ethics Guide is very clear that organizational policies must be in place to never abandon the persons receiving care.” When I asked Ruetz about health workers’ concerns that medically complex patients must undergo risky transfers, he says, “We have great confidence in our staff’s ability to work through the complex and nuanced realities of specific situations. . . . Thousands of safe transfers of care happen between facilities every day in Canada.”

Many legal experts and health-access advocates believe the restrictions in the ethics guide would not withstand a challenge based on the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which protects equality and bodily autonomy. If a patient argued that prohibiting MAID, abortion, or other services on the premises of Catholic hospitals is a Charter violation, they might win, potentially forcing Catholic hospitals to provide those services.

The right of individual health care workers to conscientiously object to providing certain services is well established, says University of Toronto ethicist Kerry Bowman, but that same right may not apply to institutions. “Can bricks and mortar take a position?” he asks. Daphne Gilbert, a professor of law at the University of Ottawa, explains that hospitals would have to prove not only that they have religious rights but also that these trump the rights of patients to not be discriminated against.

Organizations like Dying With Dignity Canada say they would support a patient who wanted to launch a Charter challenge against MAID restrictions at faith-based hospitals. But legal cases are hard on patients, and Charter challenges take several years. Family members could take up the fight, but after a loved one’s death, they generally want to move on. Given the public scrutiny such a challenge would face, it’s also unsurprising that women or trans people haven’t legally challenged the right of Catholic hospitals to deny trans or reproductive care. Despite this, at least one woman has challenged a Catholic hospital’s refusal, but not through the Charter. In 2007, a woman in Saskatchewan complained to the province’s Human Rights Commission, saying a Catholic hospital had discriminated against her by refusing a tubal ligation. She was awarded almost $8,000 in a settlement reached with the Saskatchewan Catholic Health Care Corporation. (While the Human Rights Commission can determine if discrimination occurred on a case-by-case basis, unlike the Supreme Court, it can’t rule on the overall legality of Catholic hospital restrictions.)

Why have doctors put up with these legally questionable rules that can hurt the patients they serve? Many told me that openly fighting restrictions could put their careers on the line. One doctor who worked at a Toronto Catholic hospital says, “It’s hard to explain to the younger generation why things are the way they are and why we haven’t advocated more. And I think that people need to remember that physicians who spoke up were really bullied. It was like, ‘Why can’t you just be quiet about this? Why are you making a big deal about this?’ And my career was threatened. If your privileges are removed, you have to declare that for the rest of your professional life. It’s a black mark on your record.”

Janine Farrell, the resident at St. Joseph’s who researched abortion referrals at Catholic hospitals, says that support for her project varied among senior physicians. Depending on their department, a physician who disagrees with Catholic health restrictions might be a lone rebel or aligned with the majority. Sources told me of colleagues who agreed with the restrictions for religious reasons. They also said many of their colleagues who don’t work primarily in reproductive or end-of-life care don’t see the negative repercussions of these rules and therefore aren’t concerned by them. And a handful of those who spoke to me saw the inconvenience of having to transfer patients as outweighed by all the benefits of Catholic-run health care: the inspired volunteers, the land and buildings the government didn’t have to pay for, and most of all, the Catholic philosophy of supporting the marginalized and the poor.

Farrell thinks there is an unreasonable fear of repercussions. She questions what she calls the Catholic bogeyman. “Where is this bogeyman? What has he actually done? Have you ever seen anyone punished?” Talking to health workers, I heard examples of doctors getting warnings, but no one knew of a doctor who had lost their privileges or a nurse who had been fired for breaching religious rules. For now, the resistance of health workers—aimed at both the restrictions and the religious symbolism in Canadian Catholic hospitals—is happening on a case-by-case basis. Health workers advocating in one place often don’t know that others are demanding the same thing elsewhere.

Even when dozens of advocates push for change, it’s not easy to challenge practices that are hundreds of years old. In the fall of 2020, Camm requested that the crucifixes be removed from St. Michael’s. Several health care providers, as well as Unity Health’s First Nations, Inuit and Métis Community Advisory Panel, also called for their removal in meetings and emails. Administrators first refused and then proposed that, if a patient voiced an issue, workers could call on the hospital’s manager of spiritual care to “facilitate covering the cross with a frame.” Finally, two months after she made the request, Camm got an email confirming that the crucifixes would be removed. But it took until the summer for most to finally come down.

In her 2017 dissertation, sister and canon law scholar Bonnie MacLellan writes about one former CEO of a Catholic hospital in Ontario, who was also a nun, who saw the clash between modern medicine and faith-based health care coming with the rollout of medicare. “We will be owned by the government and by a public-opinion-based political process which will steal the soul of Catholic health care,” she said, according to MacLellan. What she didn’t foresee, perhaps, was the degree to which the challenges to Catholic health care would come from within, from the very nurses and doctors tasked with upholding it.