Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

Late last year, Charlene Bagley shared an emotional video. In it, she calls her dad a hero and vows that she will find out exactly what happened to him. Her father, Tom Bagley, was one of the twenty-two people gunned down in Portapique, Nova Scotia, in April 2020.

In the nine-minute recording, Bagley speaks about the toll taken by eight months without her father and what it feels like to still have no concrete sense of how he died. “I continue to wake up daily with visions of what I think happened based on the very little information that we’ve received, trying to piece together the story that seems so unbelievable,” she says. “The story we’ve been told from the very beginning has changed many times. There are so many holes that one would wonder, ‘Is there something they’re trying to hide?’”

Late at night on April 18, a gunman attacked his partner in their home in the beach community of Portapique, about a ninety-minute drive north of Halifax. He burned the house down, killed his neighbours, and continued on a thirteen-hour killing spree while dressed in an RCMP uniform and driving a mock RCMP cruiser. The RCMP, which is in charge of policing in the area, relied on social media to alert the public, issuing a single tweet advising of a weapons complaint in Portapique at 11:30 p.m. Its next tweet went out shortly after 8 a.m. the following morning, this time describing the event as “an active shooter situation.” Rather than call in the nearby Truro police, the RCMP summoned its own reinforcements from Halifax and New Brunswick, both farther away. Meanwhile, the gunman’s rampage continued for several more hours before he encountered, in a bit of policing serendipity, an RCMP tactical team at a gas station in Enfield.

“There is an enormous amount of questions and uncertainty about what the RCMP did,” says Sandra McCulloch, a lawyer representing the families of the victims in a proposed class action against the RCMP and the attorneys general of Nova Scotia and Canada. The RCMP didn’t send out enough officers given the severity of the crime, their lawsuit alleges, and the force should have known it. “The RCMP failed to accept and act on credible information,” reads the statement of claim, which also condemns the force for using Twitter instead of the new provincial alert system, releasing tweets that didn’t match the information given in 911 calls, and failing to call in local police, who could have responded more quickly.

The proposed class action is led by Andrew O’Brien and Tyler Blair. O’Brien’s wife was killed; Blair’s father and stepmother were killed and their house was set on fire. Their criticism of the RCMP isn’t restricted to those critical thirteen hours of the rampage itself. They condemn the force for failing to investigate past allegations that the gunman possessed illegal weapons and that he had been physically abusive to women, including his long-time girlfriend. Their lawsuit alleges the Nova Scotia attorney general failed to ensure that there were enough RCMP officers in some counties and that those officers had sufficient resources to do their jobs.

They contend, too, that the RCMP’s communication since the attack has been “high-handed, self-serving and disrespectful and is deserving of punishment.” Specifically, they say families were misled about the circumstances of their loved ones’ deaths and allege that, in one case, a car was returned with gun casings and body parts still inside.

Questions of accountability, timeliness, sensitivity to victims, and the RCMP’s ability to work well with other police forces have precedent: they all came up before Portapique, perhaps most famously in the case of Robert Pickton—the largest investigation into a Canadian serial killer, which spanned years and involved hundreds of investigators.

Pickton was arrested by Coquitlam RCMP in BC in 1997 and charged with attempted murder following a violent attack on a sex worker. At the time, both the RCMP and the Vancouver Police Department were well aware that women from the Downtown Eastside were going missing and being killed at alarming rates and that many of the victimized women were Indigenous sex workers. The RCMP corporal handling the attempted murder case clearly believed there was a connection between Pickton and the missing women, so even after the Crown stayed the charges in 1998, he made surveillance requests premised on the idea that Pickton was picking up women in Vancouver and taking them home to kill them. Pickton “was the logical suspect,” an inquiry would later determine. But it took five years to charge him with the murders.

In 2010, Vancouver’s deputy police chief, Doug LePard, released a scathing 400-page report reviewing the force’s joint investigation with the RCMP. He wrote that much of the information Vancouver police had collected about Pickton—“sufficient to justify a sustained investigation”—was passed on to the RCMP for action that never followed.

“RCMP management appears to have not understood the significance of the evidence they had,” LePard found. When two Mounties did interview Pickton, in January 2000, LePard wrote, Pickton denied killing women but was cagey when it came to whether DNA from the missing women might be found on his property. Neither Mountie asked any follow-up questions. An offer from Pickton to search his farm was another dropped lead.

Overall, the investigation was “a disaster,” says Rob Gordon, a criminologist at Simon Fraser University. “The RCMP saw themselves as being cock of the roost, and these municipal forces were lesser mortals,” Gordon says. “That’s a well-recognized problem that keeps surfacing and then disappearing again.”

In the years that followed Confederation, John A. Macdonald had a problem. Settling the Northwest Territories had become a national imperative: if Canada did not match the westward expansion of the United States, it risked being overwhelmed. Reports from the area weren’t promising. In his 1872 annual report, the adjutant-general of the Canadian militia painted a picture of “white men . . . living by sufferance, as it were, entirely at the mercy of the Indians.” How were new settlers supposed to farm? How were their cattle to roam freely?

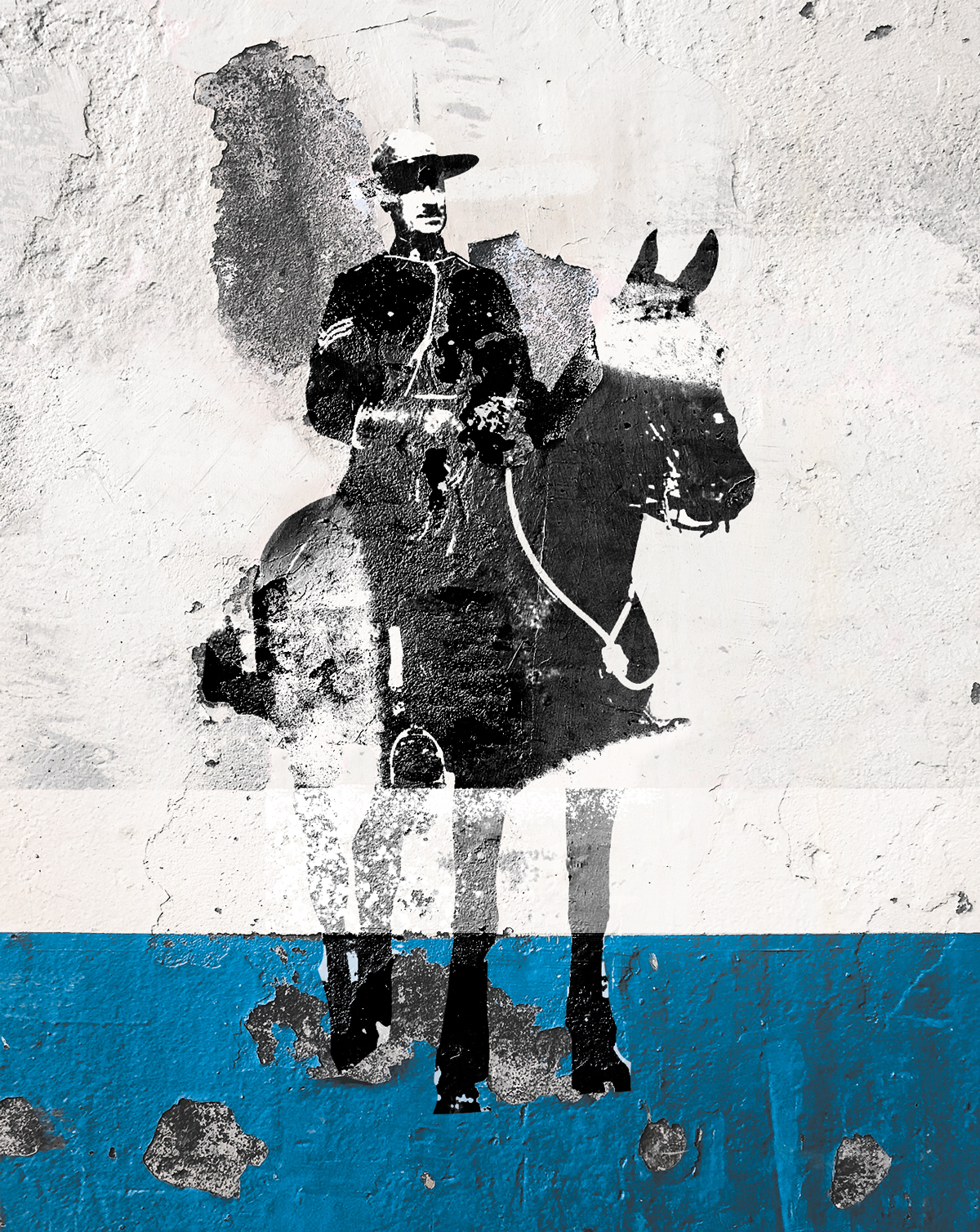

Canada’s solution was to create the North West Mounted Police, in 1873. Initially intended to be a temporary force, its purpose was to stake Canada’s claim to the territories. To that end, mounted policemen stood sentry at treaty signings, and they enforced a pass system that kept First Nations confined to reserves despite the Mounties’ own misgivings about its legality. So singular was this focus that, for a time, the Canadian government moved management of the force under the Department of Indian Affairs.

Macdonald’s design was deliberate. He called the North West Mounted Police a force instead of a corps to avoid any chance that the US might think Canada was trying to sneak west an army; he dressed them in red to invoke the British army and Queen Victoria, whose friendly relations with Indigenous peoples Canada wished to call upon; and, inspired by the constabulary the British used to rule over Ireland, he made them a paramilitary so they could serve as a de facto government on behalf of politicians back in Ottawa. (Paramilitaries are generally defined as forces that operate like unofficial armies, trained and structured as if they are going to war.)

In the nearly 150 years since they were founded, the Mounties—officially renamed the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in 1920—have gone from a couple hundred men putting out prairie fires, managing diseases, and subjugating Indigenous peoples to a full-fledged national police force. Today, the RCMP employs around 30,000 people: roughly 20,000 police officers plus additional support staff who cover everything from human resources to research and analysis to IT.

The force operates in many jurisdictions across the country and is run by a commissioner, who is the highest-ranking member of the RCMP. The commissioner is appointed by and reports to the federal government; current commissioner Brenda Lucki’s appointment was announced by prime minister Justin Trudeau, and she reports to the minister of public safety and emergency preparedness, most recently Bill Blair. (Blair declined to discuss this story; a spokesperson for Lucki wrote that she was “unavailable for interviews.”)

Locally, Mounties investigate run-of-the-mill crimes in cities and towns too small or too poor or too cheap to pay for their own police forces. Provincially, they police rural communities and patrol highways in most jurisdictions (everywhere outside of Ontario, Quebec, and pockets of Newfoundland and Labrador). Federally, they investigate terrorism and other threats to national security, and they serve as bodyguards for politicians and designated VIPs. They also police reserves through tripartite agreements with specific First Nations, the appropriate provincial or territorial government, and the federal government.

The RCMP as an institution was not built to do most of these things, never mind all of them at once. It was designed as a paramilitary the Canadian government could wield as part of its nation-building project, not a regular-duty police force with the deep community relationships and flexible, adept officers required to not just investigate crime but prevent it. So much has changed, yet the RCMP has clung to its founding conception across three centuries—and the federal politicians who are ultimately responsible for the Mounties have let them.

And why shouldn’t they? The Mounties, still, feature indelibly as part of Canada’s iconography. In 2013, 87 percent of Canadians surveyed told Statistics Canada that they believe the RCMP is important to their national identity, ranking only three things higher: the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the flag, and the anthem. Hockey was down in fifth place. A sport affectionately seen as a Canadian way of life figures less in the country’s identity than the national force.

For almost as long as there have been Mounties, there has been a brand to go along with the actual officers, romanticizing their morality—a brand invoked not just by the RCMP itself but by cultural creators of all kinds. In twentieth-century novels, the Mounties’ early days are stripped of context and transformed into adventurous tales of white men testing their hardiness against the Prairies, their mere presence encouraging even the foolhardiest of criminals to reconsider their actions. The Mounties have been featured heroically in TV shows (Due South) and amusingly in cartoons (The Dudley Do-Right Show) and had appeared (as per the RCMP’s own web page dedicated to its depictions, titled “Our image”) in “more than 250 English language movies” by the 1950s alone. At no other organization in this country can you pull on your dress uniform and instantly become an emblem of what it means to be Canadian.

That standard narrative has been confounded, more recently, by a much darker version of the RCMP, which has spent the last two decades lurching from crisis to crisis. The difficulties are complex and fall into several categories.

One recurring problem—which dates back decades—is the quality of the RCMP’s investigations, many of which have been bungled with disastrous results. In 2013, the force manufactured a terrorism case against a couple in BC. Famously, the force’s shoddy investigative work in another terrorism case resulted in unverified information being shared with the US, leading to Canadian citizen Maher Arar spending a year being tortured abroad. The RCMP’s continual struggle to understand racialized communities contributed to its failure to both prevent the 1985 Air India bombing—the worst terrorist attack in Canadian history—and properly investigate it.

The second problem is a workplace culture that is inculcated and preserved within the RCMP’s nineteenth-century paramilitary structure. The resulting well-documented internal dysfunction bleeds into the public realm through a firehose of class action suits seeking recompense for bullying, harassment, sexual abuse, sexual harassment, racism aimed at civilians, racism aimed at colleagues, and other issues that the RCMP has failed to adequately address. It has also led to decades of study and thousands of pages of reform proposals issued by a wide range of experts, almost none of which have led to substantive change.

The RCMP’s third major problem stems from its volume of work and the complicated scope of its mandate. From First Nations to municipalities to provinces and territories to national security, the Mounties’ attention and resources are divided. This makes it difficult for the force to prioritize, which in turn prevents it from focusing on those areas where a national police force is truly required, like investigating terrorism.

Accountability mechanisms meant to provide oversight of the RCMP exist, but they have no teeth: none has the legal ability to force the Mounties to comply with its recommendations. The federal government does have the power to force change, but to date, politicians have largely opted for less-substantive reform. And court victories that would seem to serve as a check on the force are often hollow: in July, for instance, the BC Supreme Court found in favour of a press coalition objecting to RCMP restrictions on reporters covering old-growth-logging protests in Fairy Creek, but the decision only called on the RCMP to reevaluate its actions, not to change them. Within a month, another journalist was detained.

There is good, undoubtedly, being done within and by the RCMP. History is dotted with Mounties who have sought to de-escalate conflict, to do what is best for the community over what is best for Ottawa, to investigate on their own personal time in order to solve sensitive cases with ticking clocks. “I suppose it’s always the case with policing, as it certainly is with intelligence, that you hear about the failures—you don’t hear about the successes as much,” says Reg Whitaker, a professor emeritus in political science at York University whose research has focused on political policing in Canada. “But clearly the problems that have led to the demands, the increasing volume of demands, for structural change and greater accountability and so on—those clearly should prevail at some point.”

The mystique that has helped cement the RCMP as a national symbol is also what renders it particularly, stubbornly difficult to reform.

All bureaucracies are complicated and built to self-perpetuate; reform is often slow, and troubles are difficult to pin down to one or two simple causes. But, with the Mounties, the stakes are higher and the problems more acute: policing is, without hyperbole, a life-or-death matter, and paramilitaries are some of the most reluctant to change of all bureaucracies due to an inherently secretive, soldierly mentality that prioritizes government aims over individual rights and views offenders as enemies. The very structure of a paramilitary institution, to borrow from two American policing experts, “subverts democratic policing.”

The fundamental challenge, say the historians, criminologists, and journalists who study the RCMP, has long been getting Canadians to see past the red-serge image: the powerful mystique that has helped cement the RCMP’s position as a national symbol is also what renders it particularly, stubbornly difficult to reform. As journalist Peter C. Newman wrote in Maclean’s in 1972, “Confusion between what is true and what bureaucrats would like to be true is the occupational hazard of any institution which, like the RCMP, expends a great deal of its energy projecting an image. Undue emphasis on the image protects the force’s officials not just from the real world but from their own consciences.”

The RCMP is responsible for handling just 22 percent of requests for police help, including 911 calls, nationwide. But Canadians who’ve never encountered a Mountie in real life still have an idea of what the Mounties are—and, crucially, that’s often a very different impression than the one held by people who are directly policed by the force. In Canada, the Mounties are “the sacred and the profane,” says University of Ottawa criminologist Michael Kempa. “If you mess them up, you offend people’s sacred sensibilities. If you get it right, you don’t really impact very many people’s profane experience of policing in Canada.”

By the early twentieth century, First Nations had been corralled onto reserves and the Mounties were looking for more work. They found it by pitching themselves as a proper national police force. The force’s commissioner sold the federal government on the idea of a coordinated paramilitary with “freedom from local influence.” The force’s longevity seemed all but assured by 1928, when Saskatchewan negotiated a contract with the RCMP, replacing its provincial police force with a detachment of Mounties.

It was cheaper for the province to outsource its law enforcement, and it still is: the federal government subsidizes the Mounties by 30 percent (provinces and territories pay the remainder). The Great Depression spurred Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Manitoba, and Alberta to follow suit. In 1950, British Columbia and Newfoundland and Labrador made the change too, leaving Ontario and Quebec as outliers. Within provinces that employ the RCMP, the force was further subcontracted to cities and small communities that wanted its services. Over a period of about twenty-five years, the RCMP cemented coast-to-coast, multilevel power.

It’s power that the federal government hasn’t shied away from using, right from the earliest days of this contracting arrangement. In 1935, hundreds of unemployed workers began a protest march, starting in relief camps in BC and heading to Ottawa. Over the explicit objections of the Saskatchewan government, the federal government ordered the RCMP to stop the protest, dubbed the On-to-Ottawa Trek, in Regina. The result was a deadly police riot.

To a certain extent, every police force operates as a paramilitary. Indeed, the volume of civilian police forces adopting military tactics, gear, and protocol has, of late, raised alarm bells across North America because militarization changes how police act by changing the terms of their job. But, even among an increasing cohort, the Mounties are unique. Their paramilitarism is built into their operational core such that they function with an army-like attention to rank that might make sense during a terrorist attack but not when policing delicate personal scenarios, not all of which can or should be resolved with arrests.

The RCMP has a well-documented history of struggling to differentiate between legitimate threats to national security and lawful political dissent.

Paramilitaries are also inherently political—fighting against governments or for them. As such, the RCMP has a well-documented history of struggling to differentiate between legitimate threats to national security and lawful political dissent. The RCMP’s countersubversion unit catastrophized its way through the Cold War, terrorizing suspected communists and destroying their livelihoods on the thinnest of evidence. In 1971, a senior Mountie, worried about the difficulties of spying on lawful political parties, posed as an FLQ cell member and advised the militant separatists against giving up their arms and joining the Parti Québécois to fight for separatism through nonviolent means.

In 1978, after the RCMP’s illegal activities blew up—literally, then figuratively—the Quebec commission tasked with investigating was forced to fight to the Supreme Court to do its job. The country’s top court issued a decision that not only hobbled the provincial commission’s work but carried ramifications that continue today: the federal government’s right to manage the force “is unquestioned,” the court ruled. “No provincial authority may intrude.”

The RCMP maintains that its contract-policing agreements with provinces and municipalities are beneficial because they “allow for the seamless sharing of intelligence and high-level cooperation between all levels of policing.” This is not borne out by history. The largest mass killing in Canada took place on June 23, 1985, when Canadian Sikh militants planted a bomb on Air India flight 182. Everyone on board was killed: 307 passengers and twenty-two crew. In 2010, former Supreme Court justice John Major released his final report of the public inquiry into the bombing. In unpacking the “cascading series of errors” that led to the attack, Major highlighted the myriad ways RCMP operations had been neither seamless nor collaborative.

Major documented how, both before the bombing—when there were multiple, specific indicators that a homegrown attack was imminent—and after it, the RCMP resisted “inclusive decision-making” and provided information, internally and externally, that “was often insufficient.” During the nearly twenty-year investigation, other police forces, frustrated with being poorly spoon-fed intelligence by the RCMP, asked Ottawa if they could skip the middleman and go directly to the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, which was tasked with collecting intelligence.

The Mounties wear many hats—probably too many hats, Major suggested in his report. (Among the world’s democratic police forces, the RCMP is the only one that operates across so many jurisdictions.) He recommended that Canada consider removing the RCMP from its contract-policing role—leaving local policing to local governments and provincial policing to provincial governments—so it could do a better job safeguarding national security.

Those who study policing reform and, in particular, Mountie history have frequently made similar suggestions that the RCMP narrow the scope of its work. To drive the point home, Christian Leuprecht, a Royal Military College and Queen’s University professor, memorably described the RCMP to me as the McDonald’s of police agencies. Whether you’re in Nova Scotia, Manitoba, or British Columbia, the Egg McMuffin is still an Egg McMuffin. The problem? Not everyone wants McDonald’s. And those franchises that want to tailor their menus to the communities they serve need corporate’s approval, and corporate has an image to think of, a budget to manage, and a head-spinning number of balls in the air.

“I don’t think the Mounties are currently particularly well structured to deliver on the needs, values, and expectations of local communities precisely because they are a very hierarchical, top-down organization,” Leuprecht says. After all, by definition, community policing is decentralized—the opposite of a paramilitary structure—to allow for local communities to dictate their own priorities (such as ensuring the force’s demographics match the community’s or deciding which neighbourhoods may require a greater police presence) beyond traditional crime-fighting.

In 2009, a year before Major’s report encouraged the federal government to reevaluate contract policing, Kash Heed—who had, before entering politics, spent three decades as a Vancouver police officer—was appointed BC solicitor general. And Heed wanted the RCMP, which had been operating there for almost sixty years, out of the province. The force emanates this “superiority,” Heed says. In his experience, he found them as rigid and uncompromising as the expert reports indicate.

While Heed wasn’t able to follow through on removing the RCMP from BC, the force didn’t entirely quell its critics. When fresh twenty-year provincial contracts were signed coast to coast, provinces walked away with new powers when it came to things like policing standards and staffing levels. Notably, the contracts include an “escape clause” that allows any province, territory, or municipality to give two years’ notice if they want to create their own alternative force—a clause that Surrey activated in 2018 and that Alberta is now deciding whether to invoke.

The paramilitarism underlying some of the most headline-grabbing RCMP scandals shapes every aspect of the force—starting with recruitment. To join the RCMP, a person must be at least eighteen years old, be a fully licensed driver, and have the equivalent of a high school diploma. There are medical assessments and physical standards to pass and some questions about willingness to take on the job. (Will you agree to spend half a year training in Regina? To be relocated anywhere in Canada? Will you be okay holding a gun? Using physical force?)

Future Mounties also need to pass a battery of tests to prove their aptitude. The first looks at personality, evaluating independence, industriousness, and methodicalness, as well as extraversion, agreeableness, and openness to experiences. The second is an assessment of seven skills the force considers “essential in executing” a regular officer’s duties: memory, composition, logic, judgment, comprehension, computation, and observation. An average of 10,000 people try to prove their fitness every year, according to the force, although its struggle to maintain its ranks seems to indicate most don’t pass.

A 2020 in-house assessment of RCMP recruitment deemed it inadequate for ensuring “the achievement of its goals and objectives.” Changes to increase recruitment didn’t seem to have been rooted in any particular evidence, and many weren’t monitored to ensure they were working. Attrition rates rose 11 percent during the 2010s, though staffing needs grew by 8 percent during roughly the same period. The force’s attempts at diversification have stalled, with some Indigenous officers citing racism within the ranks as their rationale for giving up the red serge. Earlier this year, the RCMP issued a request for proposals to revamp its entrance exams, acknowledging that the existing system “potentially favours one group over another” and “demonstrates inherent cultural biases.”

Once an applicant is accepted, it’s off to the RCMP’s training academy at Depot Division. Unlike the recruits who go on to make up municipal police forces, RCMP cadets are all sent away for their training, living and learning in an environment that’s detached from the communities they will eventually serve. This, observers say, fosters a very single-minded and homogeneous approach to policing and creates, within cadets, a deeper tie to the RCMP as an institution than to the people they police.

Mounties are forged at Depot in a paramilitary environment the force says is necessary to ensure they leave with “a high level of self-discipline.” Leuprecht, the Royal Military College professor, testifying to a House of Commons public safety committee in 2020, noted that Depot “socializes a certain type of command and control mindset”—do what your superiors tell you to do because they told you to do it, even if it’s wrong.

That mindset was on display in a twenty-minute video, published by a news website in February 2020 and shared on various RCMP social media accounts, highlighting “what sets the RCMP apart.” In it, a superior tells a cadet, “There’s no room for meek and mild in this job.” You see Mountie recruits learn to march like a military band as trainers bark at them for scuffed belts, crooked pocket flaps, and feet not quite in alignment in the drill hall.

“A cow sacrificed their life for your belt,” a drill instructor tells a trainee. “Look what you’ve done to it.”

“Do you need to see a chiropractor or something?” barks another. “Put your feet forward.”

Later, another instructor criticizes the height of a recruit’s tie clip and asks him, “Why are those things important in our uniform?”

“Public perception of us,” the recruit responds.

“What happens if we have poor public perception?” she presses.

“Lack of faith,” he tells her.

When critics raised concern over the techniques in the video, the RCMP demurred, saying it was a snapshot that omitted the less camera-friendly classroom discussions about mental health and community relationships. But that defence reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of paramilitarism. Not only are paramilitaries inherently political, but over decades of studies, researchers have found they are tied to political repression because they inculcate an us-versus-them mentality that turns every issue into a question of national security requiring a forceful response and just enough secrecy to make postmortem evaluations difficult. Studies also tie paramilitarism to corruption, brutality, and inefficiency.

Combined with the Mounties’ symbolism, this dynamic can not only impede efforts at reform but be corrosive: at times, concern over the force’s reputation has harmed its own officers and undermined decision making, dissuading the RCMP from making responsible choices when doing so could lead to bad press.

Sergeant Pierre Lemaitre was the RCMP spokesperson on call the day, in 2007, that Robert Dziekański was in the process of immigrating at the Vancouver airport. Dziekański, who spoke no English, became increasingly agitated as he struggled to figure out how to exit customs. Several hours later, the RCMP was called after a distraught Dziekański broke a folding table against a glass wall and a computer against the floor. After a few moments of attempted conversation, Dziekański grabbed a stapler, which the Mounties took as threatening; one of the officers tasered Dziekański, who died at the scene. The information investigators gave Lemaitre about the incident, which he then relayed to the public, was not entirely correct: among other things, more officers responded to the situation and tasered Dziekański more times than had initially been described—a situation that became apparent once a video of the encounter was released.

According to a statement of claim in the civil suit his wife brought, Lemaitre’s superiors forbade him from correcting the public record. He was demoted and transferred—the second time he paid a price for trying to be transparent and accountable. (On a previous occasion, he’d filed a sexual harassment complaint, on a journalist’s behalf, against his superior and was soon transferred out of the unit.) The toll on his mental health was so severe that, in July 2013, Lemaitre killed himself.

In June, Parliament’s public safety committee issued a report calling for “a complete overhaul” of the RCMP’s culture and training, acknowledging the ways in which paramilitarism constrains the actions of even those with the best intentions. It also recommended the creation of a proper training college with fresh teachers and new national standards emphasizing de-escalation training and cultural competency. In his testimony to the committee, University of Toronto law professor Kent Roach said RCMP officers “are paid as educated professionals” yet managed via a “quasi-criminal discipline process.” Instead, he said, they should “be subject to licence suspension just like teachers and lawyers are.”

This was far from the only time federal officials had been told the force should operate less like an army. Roach’s words echoed comments made by David Brown in a 2007 report following the RCMP’s pension-fund scandal, by Liberal MP Judy Sgro and former Liberal senator Grant Mitchell in a 2014 government report prompted by sexual harassment allegations, and by former Supreme Court justice Michel Bastarache in a 2020 report. Historians and critics have been raising concerns through their own research for decades longer.

As has been the case with all these earlier calls for reform, the parliamentary committee’s report has no force behind it: the Mounties are not obliged to follow its recommendations and, to date, have given no indication that they intend to do so.

In the extreme, failure to reform takes a toll not just on the RCMP’s investigative capacities but on the Mounties entrusted to lead those investigations. Abuses within the system have cost Canada good police officers and strong leaders, sidelining some of the very people the RCMP could most benefit from.

On paper, Suki Manj was the kind of leader a modernized RCMP would want. Manj had been a Mountie for almost two decades, most recently in BC’s Lower Mainland, when, in 2014, he was promoted to inspector and posted to lead the Lloydminster detachment, along the Alberta-Saskatchewan border. For the first year, Manj appeared to be well respected by his officers. A 2015 evaluation depicts him in mostly glowing terms. Colleagues described Manj as passionate, able to articulate his ideas in ways that “often create excitement in his followers,” and good at providing rationales for tough decisions. One wrote that Manj had “completely changed the attitude and daily function of our detachment in the past 10 months.”

Manj told me he’d never seen a detachment in quite such disarray as Lloydminster when he arrived. He soon got the impression that his superiors didn’t have much time or inclination to help him adjust to his new role. He says they took a hands-off approach while making him feel somehow at fault for not running every change he made by them. Near Christmas 2015, when Manj began to suspect that two people in the detachment were romantically involved and asked them to declare it, per the force’s workplace relationship policy, the environment in the detachment fell apart.

By January 2016, people inside and outside the RCMP office were buzzing about a relationship between the Lloydminster office manager and one of the detachment’s constables. However, neither the constable nor the office manager—both of whom were married to other people—were willing to admit it. Manj felt he had no choice but to force the point so the relationship could be properly evaluated for potential conflict of interest. The issue consumed the detachment: it was, as one sergeant summarized, Team Manj versus Team Office Manager.

In May 2016, Manj and the office manager in question were each called into meetings with Manj’s superiors; during hers, the office manager continued to deny the relationship. The damage to Manj’s leadership was done. That month, Manj says, his superiors told him he would be transferred; he felt it was implied that he should make it look like the move was his idea.

After a year that he describes as “complete and utter punishment,” the RCMP levelled code of conduct charges against Manj and his wife, Tammy Hollingsworth, a corporal in the Lloydminster detachment. (Neither Manj nor Hollingsworth reported to each other; she had gotten sucked into office politics by virtue of her friendships with the office manager and the constable’s estranged wife.) The charges alleged, among other things, that Manj had failed to abide by his superior Shahin Mehdizadeh’s instructions to “just leave [the relationship] alone” and that he had included false and misleading information in a statement. Hollingsworth faced similar charges, specifically that she had “abused her position, power and authority” as a Mountie by “conspiring” with her husband and others to learn intimate details about the constable involved so that she could pass them along to his estranged wife. Both Manj and Hollingsworth were suspended. (Neither Mehdizadeh nor an RCMP spokesperson would comment on specific details pertaining to Manj’s career.)

RCMP officers’ actions on- and off-duty are regulated through a code of conduct system. The force has one year from the time it becomes aware of a possible breach to investigate it; depending on the severity of a violation, Mounties can be reassigned, suspended with or without pay, or, in the most severe cases, fired.

In 2019, two separate conduct boards found in Manj’s and Hollingsworth’s favour. The adjudicator in Manj’s case confirmed that the relationship between the constable and the office manager had indeed been taking place, and the adjudicators in both his and Hollingsworth’s cases slammed the RCMP for how it had used the code of conduct process. They derided the force for misinterpreting evidence, taking statements in an unreliable manner, and relying on the word of the sergeant, who had made several “quantum leaps” in coming to the conclusions that she did. “Honesty, which is a core value of the RCMP, would have resolved this whole affair,” decreed the adjudicator in Hollingsworth’s case.

Manj and Hollingsworth’s situation is not the only troubling one. In 2014, the RCMP brought in changes to its disciplinary system that were intended to make the process by which it handled contraventions of its code of conduct “remedial, corrective, and educative.” They weren’t successful, according to a 2017 report by the force’s Civilian Review and Complaints Commission (CRCC), the independent federal agency responsible for handling public complaints about RCMP conduct. Per the CRCC’s report, the 2014 changes left many RCMP officers and the CRCC with the impression that “code of conduct violations are being used to target and intimidate members, particularly if they raise concerns about harassment.” The CRCC also raised concerns about the selective application of discipline, having heard “instances of retaliation and abuse of authority.” This type of organizational culture, the CRCC wrote, drags down good mental health, the integrity and efficiency of operations—even “the effectiveness of the organization as a whole.”

Despite the conduct board clearing him of wrongdoing, Manj hasn’t been back to work. Until recently, he was on what the RCMP calls “off-duty sick” but what one police psychologist cited by the CRCC said should more accurately be called “off-duty mad,” describing it as a leave that members take to escape “a toxic work environment, high levels of employee stress and a culture of fear.” As of June 2021, the number of Mounties on off-duty sick leave for six months or longer was 713. (The force doesn’t track how many of those cases stem from code of conduct issues.)

In 2019, the Liberal government created a new civilian advisory board, separate from the CRCC, to give the RCMP advice in addressing harassment, problematic workplace culture, and other management issues. (If you are losing track of all the boards, committees, and commissions that have been tasked with advising or overseeing the RCMP, that is likely because they have multiplied considerably over the years.) Like most of the other accountability mechanisms, it doesn’t have the power to compel the RCMP to make changes.

Even now, University of Ottawa criminologist Michael Kempa says it’s not apparent—at least from public-facing comments—that senior Mounties or the federal politicians in charge of them understand the magnitude of the reforms that are required.

Manj recently came to the same conclusion. In July, he signed forms to officially end his career as an RCMP officer. “No way I could go back to that company with the leadership,” he says. “It’s a gong show.” Hollingsworth remains on off-duty sick leave. She filed a lawsuit in 2019 accusing the force of malicious prosecution; her case is ongoing.

A decade ago, the RCMP’s lone civilian commissioner, William Elliott, announced a rare coup for accountability: in situations where a Mountie’s actions led to a person’s death or serious injury, provincial watchdogs (whose job is to decide whether criminal charges are warranted) would investigate. This gave provinces considerably more power to hold RCMP officers accountable for serious errors. Previously, in such cases, the Mounties themselves would investigate—which is still the case for other alleged wrongdoing, including everything from inappropriate use of force to bias against Indigenous people. (“Police investigating police” is the term generally used for this practice; most outside experts view it as biased and unfair.)

For a 2020 academic paper about the “dynamics of accountability,” Krista Stelkia, a Syilx/Tlingit researcher at Simon Fraser University with a degree in criminology, interviewed thirteen representatives from various oversight agencies within BC to outline the differences in oversight procedures between Mounties and their local counterparts. A majority of those interviewed (with the notable exception of the RCMP participants themselves) found the Mountie process ineffective and inadequate.

If a citizen lodges a complaint against a municipal police officer, it’s investigated by an in-house professional-standards unit, under the scrutiny of an independent watchdog, with a provincially mandated six-month deadline. By contrast, if a complaint is lodged against an RCMP officer, the Mounties’ in-house professional unit conducts its own review with no independent oversight and a one-year deadline that the force is known to have blown through.

The divergence between Mounties and their local counterparts is so great that one agency representative spoke to Stelkia of Mounties’ eyes widening when they were brought into other police-force investigations and saw how thorough the process was. They go away and realize, “Oh, this is not going to be a cakewalk,” he told her.

Once the RCMP completes its investigation of a complaint, if the member of the public who filed the complaint is unsatisfied with the response, they have recourse through the CRCC. Though the civilian-oversight agency cannot compel the RCMP to change its policies or practices, it can issue public reports into allegations of wrongdoing. The RCMP is required to participate in these CRCC investigations, but its average response time is seventeen months. (In 2019, the RCMP signed a memorandum of understanding with the CRCC promising to meet new timelines; like all other recommendations called for by the CRCC, it is not legally binding.)

Sometimes, the RCMP takes so long to respond to requests for information that similar subsequent complaints emerge from new sources. That happened last year, when the BC Civil Liberties Association filed a complaint to the CRCC about the RCMP’s enforcement tactics in Wet’suwet’en territory, where some First Nation members and their supporters have been blocking the construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline. The CRCC declined to investigate the complaint for a reason that was “unprecedented,” says Carly Teillet, a community lawyer with the BC Civil Liberties Association: because it was still waiting for the RCMP’s response to its investigation following twenty-one similar complaints, which had been filed by anti-shale gas protesters in New Brunswick, in 2013.

The CRCC released its final report from the New Brunswick complaints last November. It commented on significant red flags in the RCMP’s participation in the investigative process, finding that the force had made a “lengthy, point-by-point rebuttal of the Commission’s findings, without additional factual information being provided.” Instead, the CRCC noted, “the RCMP sought to substitute its own views of the evidence for those of the Commission, and to provide its own conclusions about the reasonableness of its members’ actions.”

In other words, the RCMP’s participation in an independent oversight process consisted of casting doubt on its overseers without providing them with any information to back up the force’s own version of events.

The CRCC is not the only investigative body to raise concerns about RCMP oversight. When the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) released its final report, in June 2019, Mountie apathy for investigating such cases was evident throughout. One mother recounted how the RCMP wouldn’t take her statement when she went to report her daughter missing. Such a delay, when time was of the essence, meant she might never get answers. Others spoke about how they couldn’t seem to get Mounties to speak to them respectfully during some of the most difficult moments of their lives. Others traced Mountie misconduct back even further. In 2013, when the Qikiqtani Truth Commission published a special report focusing on its policing findings, it described how, between 1950 and 1975, “some RCMP used their position of authority to coerce Inuit women into sexual acts.”

The MMIWG commissioners were unequivocal in their conclusions: “The RCMP have not proven to Canada that they are capable of holding themselves to account.”

If there ever were a window for RCMP reform, it opened in 2007, after independent investigator David Brown publicly declared the force “horribly broken.” Four years earlier, a human resources employee had sounded the alarm over problematic hiring practices, nepotism, contract splitting, and misappropriation of funds within the force. A subsequent auditor general’s report revealed that the RCMP had inappropriately used $3.1 million from the pension fund on human resources projects.

Brown, who had previously been the head of the Ontario Securities Commission, was brought in by then prime minister Stephen Harper to dig into how a scandal of that magnitude was even possible. “After sifting through the various versions of the events, the picture of the RCMP and its culture that has emerged is one of mistrust and cynicism,” Brown wrote, noting that there was an evident breach of trust between the rank-and-file and Mountie management.

Not only had the commissioner of the day, Giuliano Zaccardelli, and his team failed to respond to the scandal in a “transparent, timely, effective or thorough” manner, Brown ruled, but the members who had dared to expose the scandal “suffered personally for their efforts.” In the case of the officer who brought the wrongdoing to Zaccardelli’s attention, the commissioner was “prepared to cut a swath through the career of an officer who was highly regarded on the basis of a single meeting.” Zaccardelli had immediately ordered that the officer be transferred, and the message to Mounties across the country, Brown wrote, was “one brings bad news to the Commissioner at one’s peril.”

From the moment Brown made it apparent that the RCMP’s governance structure was broken, there was—for a time—some momentum for change. In 2008, the federal government created a reform council that produced a series of reports over the following two years. The government also brought in the force’s first and only civilian commissioner, William Elliott, for a tumultuous term that saw Elliott accused of threatening and bullying his deputies. The government handed the reins back to a seasoned officer in 2011—just as women in the RCMP began breaking their silence on sexual harassment and sexual assault within the force.

“There was a moment where the Harper government probably could have done something and it would have been lasting,” says Kempa, the University of Ottawa criminologist. There were enough senior people on the “change management team who I interviewed that clearly understood what was going on. And then it fell apart.”

The window closed in 2013, when Harper’s government received royal assent for Bill C-42, the Enhancing Royal Canadian Mounted Police Accountability Act. Bill C-42 introduced a modernized code of conduct system (the same one Manj says was used to punish him and Hollingsworth) and enabled the CRCC to review RCMP activities at will, without waiting for a specific public complaint. While the bill did include some reforms, it went only as far as changing elements within the overall system—it left the system itself intact. The RCMP remained a paramilitary organization, one without the robust external oversight experts have long said is necessary.

As Bill C-42 became law, then commissioner Bob Paulson introduced a new action plan, ready to tackle what he would later call the “very serious issue” of harassment within the force, while at the same time denying that there was a systemic problem with sexual harassment. That action plan “appears to have foundered,” the CRCC remarked in its 2017 workplace culture report, adding that “the RCMP has since moved on to the next initiative, with little regard as to whether the actions previously identified have been implemented, are leading to meaningful change, or, indeed, have further exacerbated the problems they are meant to address.”

In June, questions of transparency, accountability, and the RCMP’s priorities came roaring back into headlines when Frank Magazine published some of the 911 calls made during the mass murder in Portapique. (The calls have since been taken offline, but transcripts remain.) In the first recording, made at 10:01 p.m., an operator is told by Tyler Blair’s stepmother that her husband has been shot and that there is a police car in front of her house. In the second call, fifteen minutes later, Blair’s brother says that his mother has been murdered and that the man who did it drove away in a police car. The recordings clearly call into question the timeline of the attack that the RCMP offered publicly, in which the force indicated it had not “confirmed” that the gunman was driving a police car until 6 a.m. the next morning.

Soon afterward, the RCMP issued its first update on the investigation in six months—not to respond to the substance of what had been released but to condemn the publication of the 911 calls. According to a subsequent statement, the RCMP asked the Ontario Provincial Police to investigate the leak. It, too, did not address the revelations themselves.

What is novel and hopeful in the Portapique investigation, though, is that the federal government’s initial plan for an independent review of the mass murder—a process that would not have been able to compel evidence or force witnesses to testify—triggered sustained public outcry, forcing the government to make a swift reversal. “We have heard calls from families, survivors, advocates, and Nova Scotia Members of Parliament for more transparency,” said public safety minister Bill Blair in a statement announcing a full-fledged public inquiry—one that is able to compel the production of evidence and the testimony of RCMP officers.

The inquiry’s final report is due in November 2022. It’s clear that many Nova Scotians are outraged by the RCMP’s response to this killing spree. While the public inquiry was a good move politically, Gordon, the Simon Fraser University criminologist, says only time will tell whether its examination of the Mounties’ handling of the murders will draw connections with the systemic and cultural issues impeding RCMP reform across the country.

Even if it does situate recent events in their full context, the Portapique report will likely find itself reiterating what many before it have already thoroughly explained. So the question remains: Will another inquiry and another report spark enough momentum for more genuine reforms? “People are very upset by what happened, the conduct of the RCMP in particular,” Gordon says. “Whether it will produce any bigger and better results is really hard to say.”