Sands was an old bitch to begin with.

That was the bare truth of it, and Sara knew it too. Even if she didn’t like to say. You don’t like to say a thing. But sometimes, of course, you can’t help it. Can you?

Sara had seen her hose a cat once, just to get it out of the yard.

Never a word to the neighbours. Stood in the doorway and glared if you so much as skimmed the bare parking spot in front of her house. She was the kind to clear the spot in winter but string up a No Parking sign, stretched between two old lawn chairs, so that no one else used it. She didn’t even clear it herself. Was her nephew who cleared it, or her cousin’s son.

“And she with a perfectly good garage. Sure, I bet she doesn’t even use that spot,” Fannie said, calling from the next room. Fannie’s hair was piled up on top of her head, and she had one foot propped on a chair, her focus almost entirely on toe polish rather than the house next door.

Sara nodded. Cautious, though. She was standing at the living-room window, to one side, mostly hidden in the ruffle of the sheer. Watching the action in the driveway.

Sands. Mrs. Sands, she supposed, although there was no man on the premises. But the old lady wore a ring. Sara had seen it, shimmering against the steering wheel when her car rumbled past the house. A Buick.

“She’s all alone,” Sara said. Then, louder: “And unliked. You put yourself at risk when you move through the world like that.”

It was not winter now. It was July, and a good one—another thing you don’t like to say. Who wants to jinx good weather?

The action in Sands’s driveway was a yard sale.

This, by itself, was unremarkable. But every weekend? For the whole month? Saturday and Sunday, both. And early! Sara had a shift tending bar at Rascalz, Thursday to Saturday, the living-large tip nights, so most of the time she only crawled into bed around five. By seven, the noise of set-up had begun. Close to the grave if she didn’t get some sleep soon, she told Fannie now. She couldn’t complain to Harding, because he didn’t approve of the bar and she didn’t like to fight about it.

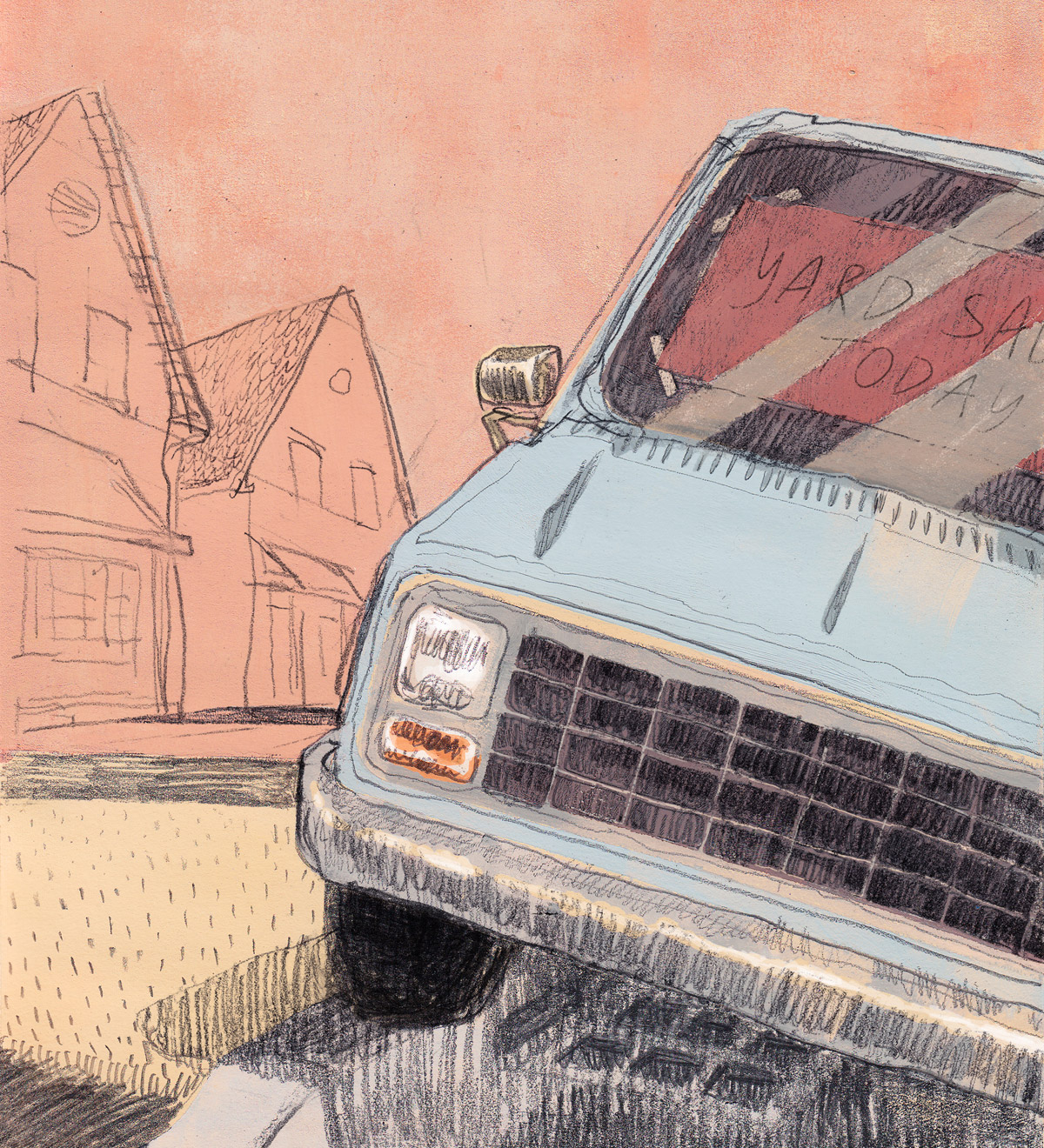

Sara inched closer to the window. There was a junk minivan pulled up onto the curb, with a placard in both windshields: YARD SALE TODAY. This may have been the be-all of the marketing plan. Whether the thing was advertised on the buy-and-sell sites, Sara didn’t know, but there were never any other signs posted, no box ends, no bristol board Sharpied and stapled to the hydro poles at either end of the street.

The troubling part was that Mrs. Sands didn’t seem to be involved. Sara hadn’t seen her since the sales had begun. Not in the garden or floating by in the blue Buick, driving out for milk.

Not at all.

Instead, a man in Adidas shorts and an old George Street Festival T-shirt paced the sale tables, a cash belt strapped to his waist.

“It’s the nephew, yeah.” Fannie swept in from the kitchen to peer over Sara’s shoulder. “Lives up Barnes Road. The sketchy end. I used to see him in line for his bagels on Saturday mornings. But now I s’pose he’s here every Saturday.”

The nephew was the owner of the minivan. Early thirties, Sara thought. Not quite what you’d call a skeet.

“But those are his people,” Fannie said. “That’s what you mean: of skeet stock.” She turned from the window, casting about for where she’d left her sandals. “Familiar,” she said, “with the stolen-meat trade.”

“I feel like I should ask him about her. Or someone,” Sara said. “Who would you ask about a thing like this?”

“Car’s still there?” Fannie said.

Sara nodded. The garage stood open, the glint of a blue bumper just inside.

“Maybe she’s on a vacation.”

Sara didn’t reply but let the curtain swing back into place. It brushed her bangs as it went. She did not think Mrs. Sands was on vacation. Your relations don’t sell your belongings when you go away for a few weeks of sun.

It was almost two o’clock: Harding would be home soon. Sara glanced down at her phone for the time and then again to make sure he hadn’t texted.

She let Fannie out the back way, just in case.

“What do you care?”

Harding had the laptop open, clicking away. He’d kicked off his sneakers on his way in the door, and they lay there, piled up with the other shoes. Imelda, Fannie called him. Sara was in bare feet. She twisted a bit of her T-shirt around a finger and let it go. The T-shirt with a fringe of wrinkles along the bottom edge.

“You don’t think it’s strange?”

“If she’s dead, she’s dead. People die.”

Onscreen, she could see tiny men on horses, jousting around. Not jousting. Whatever they did in the game to win or lose or kill each other. Harding said whenever Sara came around talking, she made him die.

He slapped the screen shut, disgusted.

“Cec says your sister’s in town. Back from Canada. From the u-ni-ver-sity.”

Sara nodded in a noncommittal way, casual, then turned quickly to wash a pot that had been left standing in the sink.

“Fannie? Oh, yeah. Yeah. She’s around.”

“But not around here.”

Sara said no.

He had to go out to Mount Pearl for an eye exam on Monday, so Sara drove him, and they sat, afterwards, in the restaurant at the Irving under the glass dome, Harding still squinting against the light. Sara read him the menu. There was breakfast you could get all day and club sandwiches and bacon sandwiches, with that bargain mayonnaise that tastes like Miracle Whip, she reminded him, and a hot turkey and a hot beef with either one or two slices of bread. Besides that, just the usual dinners: spaghetti goulash, liver and onions. Suppers, Sara said, only old people order: “What’ll happen to the liver industry, when everyone over sixty-five is gone?”

But thinking of old people made her think of old Sands, and she didn’t mean to get back into that.

There were three soups on the board: Turkey vegetable, fish chowder, pea. While they were waiting for their eggs and bacon, Sara watched the man in the booth behind them.

“He’s got a shirt that says Las Vegas and a hat that says Las Vegas.” She leaned into the jam rack, so the man wouldn’t notice her staring. “When we arrived, he was eating turkey soup. Not a side bowl, but a proper bowl, a proper bowl of soup. Now he’s just finishing, still scraping at it, and the waitress comes and gives him a second bowl of soup.” She nodded, more to herself than anything. “It’s pea. Pea with a dumpling. Again, a proper bowl. Two soups. Who orders two soups?”

Harding had his eyes closed:

“Honest to fuck.”

She straightened but kept an eye on the man, with furtive glances anyway.

“I’ll tell you what I think,” Sara said, but then Harding opened his eyes and looked at her and she didn’t tell him any more.

When they were home, Harding slumped on the couch with his dark glasses on, and she went out to buy their beers on foot, because it meant she could cut through the cemetery. There was more than one graveyard in town, surely, but isn’t there some unspoken law of burial? If the old woman was dead, wouldn’t they have put her in the ground close to home?

“She’s not a dog, Sara-bear. They don’t just dig a hole in the backyard and put a rock with your name on it and a paw print.” Fannie picked through the shrub around the graves and popped the cap on a Jockey.

Sara toed at a weedy flower with her boot. There were reports of a new kind of weed: something that burns you, real burns, the blisters hanging on for months and flaring up whenever sunlight hits your skin. She sucked her hands up into her sleeves.

“Most of these are not what I’d call current,” Fannie said. “Hep Ryan, b. 1921 d. 1970. Minnie Chafe, Angels Belong in Heaven. Minnie! Imagine walking around like that. If I had a girl, what would I call her? Not Minnie. Margarita, maybe.”

Sara said if she had a baby girl, she’d always give it a boy’s name, like Leslie or Seton or George. So that the world treats it better.

Fannie said if she had a girl, she’d call her Limoncella or Barack Obama or Hot Lips Houlihan.

“The newspaper,” Sara said. “The newspaper lists obituaries.”

“This seems like a lot of work for someone you don’t like.”

Sara picked up Fannie’s beer cap from where it was lying on the ground and slipped it into her pocket.

“I just like to be cognizant,” she said. “I like to keep track. Who’s dead and who’s still living.”

On wednesday, Harding went out of town for a few hours, and she wondered if he would hit a moose. On his way home, because it would be twilight then, the grey time where you hear most about that kind of accident. A moose defies your expectations. You see pictures, or even, the odd time, a real one, mawing at the side of the highway, but you never can know how big they are until you hit one with your car.

Hit a moose and you only take it out at the knees. It’s less the impact than the weight of the thing falling into your windshield that kills you.

Sara stood at the window, her cellphone pressed to her ear. The minivan was there, up on the curb, the engine clicking as it cooled.

“What’s he here on a Wednesday for?”

This came out in a whisper. She didn’t want the nephew to hear her, if he were outside in the side yard where she couldn’t see him but somehow he could still hear her through the glass.

“How long has he been there?” Fannie said.

“Thirteen minutes. Didn’t take anything into the house. Hasn’t brought anything out. He might be in the backyard.”

“You know, if she was on vacation, he might be looking after things. The garden or whatever.” Fannie was washing the dishes as she talked, the clink of cutlery a steady background distraction. “Why don’t you come over here for the night?” she said suddenly. “Lots of room. Or I could come there. If you’re alone, anyway.” She waited a moment for Sara to respond. Then: “I’m not afraid of him, you know.”

Sara didn’t say anything back. There was a distant thud, like a door slamming somewhere, and then a true slam, the front door, and the nephew striding back out to the van. The squeal as he worked to get it going. She lay a thumb on the screen’s red circle and hung up.

The sun was gone, and Harding still had not come. She wished he would call: it’s better to know, is he or isn’t he. Before you go doing anything with your time. Outside, the grass was cool under her feet and rough where the weeds had been mowed down to stubs, and she suddenly remembered the burning weed and was sorry she hadn’t put on shoes.

But she wanted to be quick.

She wanted to be quick and stealthy, sort of in case the nephew came back, which she knew he wouldn’t, so really in case Harding came back. Which he would, eventually—unless there had been the moose.

She wished for a moment that Fannie were there after all, but then she recanted.

The latch on the back gate was brass, with a little string pulley in case you wanted to open it from the other side. In the backyard, the old lady had a deck that was blue painted and a café set with no umbrella and no cushions, just hard metal chairs that baked and rusted, depending on the season. There was a sliding door, but it was locked.

At the edge of the house, she caught a gap in the decking and dropped down to her knees to follow it, running her fingers along the seam. She picked in with her fingernails to see if the panel would lift.

There was a snap from the front porch. Sara froze. The motion sensor flickered on, vague and squandered, a reverberation of light, shining wanly through the window at the front and across the smooth floors of the house, then glowing at her through the glass of the back door. A glimmer. Sara waited. There was no noise or car door or anything, and she thought, a cat, a rat. A shopping bag abandoned to blow down the street, down to the harbour, to float away, to choke a sea turtle, to wash up somewhere far away and start again.

She wedged her fingers and pulled. A kind of trap door creaked open in the deck, revealing the ramp to the cellar below.

A root cellar: Sands must have had the deck built on top to hide it, the cement crumbling a little. At the foot of the ramp, there was a wooden door with a flimsy lock, leading into the house. No work to get inside.

The back basement had the same crumbling floor. An oil furnace the size of a church organ, deep red in colour, took up a whole corner of the room. There was a sprung mousetrap near the foot of the stairs with only some dusty bones in it, the lace framework of a former mouse. She touched a foot to the bottom step and it creaked, and between the slats, she saw something move.

“Mrs. Sands?”

Sara called the name up the stairs, a safeguard, but she did not expect a response, and none came. Above her head, a pull chain dangled from a bare lightbulb screwed into the ceiling. With the light on, she knelt on the steps and peered through.

A cat, a mama cat. Tortoise shelled. A few dead kittens sprawled around. The mother too sick to bother eating them, even. An inauspicious item of evidence: the cat must have snuck in somehow, in the time the old lady had been gone.

The cat’s tail wavered, a ripple. Sara reached through the slats. Just one baby left: a calico. Calicoes are always girls.

Sara tucked it into her shirt.

upstairs, the house was cool and silent. A vacuum track marked the carpet behind the couch, but there was dust on the mantel, a chalk outline of where the knick-knacks used to stand. By the bay window, divots in the pile: the feet of missing armchairs. The nephew methodical in his work.

She’d been inside the house just one other time: a year ago Christmas, when she’d seen the old lady trip on her own front stoop. There had been the vacuum marks then too; Sands shakily pouring out two cups of tea. The house just as pristine but with more things in it.

A rattle from the kitchen made her jump, but it was the refrigerator thrumming to life. Sara opened the door, and the sound tapered away. When she turned, there was another Sara, reflected in the sliding door to the backyard. The bare-bulb glow around her in the glass. She closed the fridge, and the room went dark.

In the cupboard, she found a can of Millionaires sardines and opened it up with the tab, enticing the kitten to lick the fishy oil from her thumb, and they wandered together to the front entranceway, a cherry-wood banister snaking down to greet them from the second floor. Something else too. Down in the rug, at the foot of the stairs: something small and dark, mottled. A leaf. Half-rotted. Half-crushed.

She might not have noticed, only the rest of the house was so clean.

Sara tilted her face up. There was a vase, broken and lying on its side, on the landing above her. She could see the flowers. Peonies. The heads just skulls, fuzzy with mould.

As though there’d been an accident. As though someone had caught the edge of the table as they shoved their way past. The old lady alone in the house.

Someone in a terrible rush.

A trail led down to where she stood at the base of the stairs: more leaves, and white petals, curled and drying. Sara took a step up onto the first tread but changed her mind, falling back again. Something about the spilled vase. She didn’t move but waited there a moment longer. The kitten searching her fingertip with a rough tongue.

He hadn’t started on the upstairs yet. The nephew. That was all.

she came out the side door of the house, rather than retracing her steps, and was still standing there in the dark drive when his headlights swung in, lighting her up. The kitten a ball in her hands.

“What you got there?”

Harding smacked the driver’s door shut.

Sara said she’d got it from the shelter, that he didn’t have to worry. It had its shots.

“What about worms?” He didn’t like pets, a thing she knew. If she was going to force some creature on him, why hadn’t she got a dog, at least? He was talking to her over the roof of the Sportage.

Sara said he wouldn’t even know the cat was there.

“Sure, it’s only little.” She walked around to the front door, shoulders caved, her chest a nest.

She said she’d named it Jim.

kitten jim made her week more complicated, to be certain. Easy enough at home in a shoebox. A bit different in her purse, mewling, below the bar at Rascalz.

“Still doesn’t mean she’s dead.” Fannie took a sip from her straw, the grenadine pink rising from the glass to her mouth and falling back again.

“It does. It does mean that. You can see that it does.”

“Could’ve had a fall. Could be at St. Clare’s. Could be in a home, for all you know.”

Sara cracked a snack pack of cottage cheese and held a curd out for Jim, in her finger’s crook. The kitten’s appetite tentative, but only at first. She leaned across the bar.

“Fannie, what if he killed her? That’s what I’m thinking. That’s what’s got me worried. The nephew.”

“Killed her! Bagel skeet? Nah.” Fannie put the glass down. “Well? I guess people do.”

“The place is too well kept. She had money, believe it.” Sara petted the kitten’s tiny crown. She picked a flea from its ear.

“Nah.” This was decisive. “You’re looking for something that’s not there. Sometimes worries cross over. You do seem awfully focused, if you know what I mean. On some old lady.”

Sara looked up. On the other side of the room, Luke Murphy leaned hard on a table, four beers in. Luke was Fannie’s sometimes-boyfriend; her on-again-on-again, Fannie called him. Sara was used to counting men’s beers. Important to know who might get unpredictable.

“If you’re back with Luke now, does that mean you’re staying? In town here.”

Fannie nodded. She was looking at Luke too. She turned back to Sara.

“I wish he was more—” Fannie squinted, thinking. “Interested. That’s not right. Easier—I wish he was easier. I don’t mean Luke,” she said, clarifying. “Your Harding.”

Sara threw a shot of Lamb’s in a glass and sprayed it with Coke.

“He’s just very private,” she said. “Some people are just private like that.”

harding was interested enough: he already knew about Fannie and Luke Murphy. He said his buddy Cecil had told him they were back together. Fannie unloading boxes out front of Luke’s house on Hayward Avenue some three weeks ago, hadn’t Sara known about that? He’d made himself a steak for lunch, and he sawed away at his plate with a too-dull knife. The steak cooked brown to the core.

Her only sister, and all this time, she hadn’t been in touch? Goes to show. Some garbage people never stop being garbage. He forked up a piece of meat and kept talking as he chewed.

“Don’t be softening up to her when she does come around,” he said. “She’ll be in to the bar to see you eventually. She’ll be in because she thinks she can talk to you there, where I’m not, and tell you things. Get your ideas bent around.”

Sara was frying an egg, the white crisping in the pan. She switched the element off and left it there to finish up, on the cooling stove, and went to the window instead.

Harding kept talking.

“When you tell her things, it always comes back around, right?” He was smiling down at his meal as he said it. “And it just makes things harder. It makes things worse. For you and for me. Right? We count, here in this house. You got to remember what we got going on. We got something here, we count.”

Sara nodded but pulled the curtain aside for a better look.

“We count,” she repeated. It was a murmur. Then: “When was the last time you saw her?”

“I told you, was Cecil saw her. Not me. Don’t you ever listen?”

“No. Not Fannie. Mrs. Sands. Next door.” Sara turned. “When would you say you saw her last?”

“What the hell are you back at this for?”

Harding put down his fork, staring. Sara let a shoulder rise and then fall again.

“If she goes, maybe we get something better.” He pushed the plate away. “I hope we get a guy with a snow blower, a real do-right type, does the whole driveway not just his half. Instead of some old biddy complaining at me that the crows been into our garbage—ours, mind you, never hers, only ours—and expecting me to crawl around picking cheese wrappers out of her weeds.”

He stood up.

Sara hedged. Harding stood between her and the stove now, like he was expecting something from her. To the other side of the room, she could see Jim’s shoebox where it sat, safe and sound, on the bookshelf. The top of it shifting a little.

She needed a vet. The fleas in the kitten’s ears were making it scratch itself bloody.

Harding followed Sara’s gaze to the shelf and the shoebox there, the lid lifting again to reveal a single ear, furry and folding over a little under the weight of the cardboard. He turned back to face her again.

“You quit that bar job yet?” A sneaky look to him, harmful. “Who’s going to look after your little cat if you’re out all night? Your friend next door?” He took a step toward the shelf. “Old bitch.” He took another step. Sara hurtled across the room to get there first.

She grabbed the shoebox, hugging it to her chest. Harding started to laugh.

“I don’t know why everyone has to be so down on this old lady,” Sara said, her voice rising. The scrabble of Jim’s little claws inside the box—she’d swung it around too fast. “Everyone has the right to live how they please. Why does she have to be cheerful? Why does she have to be perfect? This lady grew up with things, expectations. Ideas! And now she’s just an empty house, and some young man selling it off piece by piece. Change in his pocket!”

Harding’s smile was gone now. He turned and took the pan off the stove and stood with his back to her, fingers gripping the handle.

Sara could feel Jim moving around, the displacement of weight tipping the box a little to one side. She opened it up and slipped the kitten inside her shirt and held it there, then skidded the empty box across the kitchen table.

Harding spun to face her, but he only chucked the congealed egg into the sink. The pan clattering.

Sara stepped backwards to the door.

“I’m going out to buy Jim a leash,” she said. “Get those toes in the grass. Get a bit of sun.”

Out on the porch, she pressed the screen door into the latch and held it there.

at the pet store, the teenager behind the counter looked at Jim and recoiled a little.

“You oughta take her to the vet, I think. She’s got pus in her ears.” But he sold Sara some over-the-counter antibiotic cream to tide things over, and she walked home slowly, peering down at Jim in her purse, the little cat’s ears now gummy with white ointment. A bus pulled in next to her at the crosswalk, brakes labouring, and she stepped into the road behind it, emerging from a cloud of exhaust at her own street corner.

Harding’s car was still in the driveway.

She stopped for a moment, looking around. Not ready to contend with him again, or at least, not before heading off to work her shift. Mrs. Sands’s side door would likely still be unlocked—the door Sara had used to come out of the house on Wednesday night.

The nephew had not been around that she knew of. There was no one else to lock it.

She pushed her way inside, quickly, then shut the door and turned the deadbolt from within, sitting down hard on a bench against the wall. The space, in the light of day, was not so much an entrance as a mud room: there was a cubby for bug spray and sun lotion and gardening gloves, and a pair of plastic clogs, clumps of dry earth still clinging to them, upside down on the linoleum floor.

Sara waited there, catching her breath. The house itself as still as the first time she’d been inside. When she got up again, she went first to the kitchen, but nothing had been moved in her absence. The sliding door to the yard was still locked.

Down in the basement, the mother cat was dead. It wasn’t until she saw her, the limbs stiff and a weird trail of gluey blood at the side of her mouth, that Sara realized she’d been expecting that. From inside her purse, the kitten began a plaintive mewing.

Old Sands. Old Mrs. Sands’s house. She found a clean paper napkin, folded at the bottom of her purse, and lifted Jim out to retrieve it, shaking it flat and laying it over top of the dead cat and her kittens like a coroner’s blanket before picking her way back up the stairs. Then on, through the fallen peony petals, to the second floor. This time not stopping herself, not calling out or waiting to be heard.

There was vacuum track in the bedroom carpet, too, but fainter, and a lazy spider’s web strung from the bleed valve of the radiator down to the trim at the edge of the floor. The bed was made, properly, the coverlet pulled tight and tucked around the pillows. A jewellery box sat open on the vanity, a tangled string of pearls caught in the hinges, but the old lady’s diamond ring was not there.

Out in the hall, a towel rack lying on its side: Sara had to step over it twice, once on the way into the bedroom and again on the way out.

The mess was in the bathroom.

That was where she’d died. Sara could see that now. It was the only room in disarray. A stepstool shoved up against the wall, the clothes horse, everything thrown aside when the ambulance came. That’s how they do it. Isn’t it? It’s only about speed. The paramedics, probably, pushing past the table on the landing—not the old woman struggling against someone, not the old woman trying to save herself, to get away—that had ravaged the flowers.

A fall. Getting out of the bath. It must be that. Just as Fannie had predicted: Could’ve had a fall.

The blood was all still there, caked now and rusty looking, where it had run down the wall and pooled inside the tub, the rubber stopper thick with it.

She didn’t see the towel, piled in a corner, until she’d turned away. She caught the edge of it, all of a sudden, in the mirror—more blood, the towel used to soak it up, as though the old lady had fallen there, too, somehow. Her head split open against the tile.

From outside, the thunkof a car door. Sara backed out of the room, tripping over the towel rack and sprawling herself into what was left of the peonies, trying to catch her purse as it flew, her head smacking hard off the wall. A sound of footsteps out on the porch, but then only the squeak of the rusty mailbox, opening and closing again.

The kitten terribly silent, cradled in Sara’s hands.

fannie came into the bar just after they opened up, happy hour. Sara was still cleaning and refilling the fruit containers: lime, lemon, cherries from a jar. The kitten was in her purse, but there was no question that it was flagging now. She should have brought the mother along with her when she first rescued Jim. She should have been braver, bought a rabbit cage, someplace to keep them together, safe and fed for a few weeks. Why hadn’t she?

Luke took Fannie’s jacket for her and hung it on a hook by the door before sliding onto the next stool himself. Fannie had some paperwork, and she spread it out all over the bar. Brochures, Sara could see now. Full-colour photographs.

“We’ve been house hunting,” she said. Then, gauging Sara’s look: “It’s only a bit of fun.”

“Fun? I’ll buy the place whether you come along or not.” Luke pulled the brochures closer and drummed the bar top. “Give me a drink for a rich man, will you? Something for a land-owning gentleman. Fannie, what does Mr. Monopoly drink? Champagne?”

“At five in the afternoon, he drinks a gin and tonic,” Fannie said. She turned to Sara, cheeky. “And he drinks the bar gin, because that’s how he saves enough money for real estate.”

“Don’t need to save, only need to give them walls a scrub. Bit of work here and there. Lick of paint. Lick of paint.” Luke spun the papers around so Sara could see the pictures. “Estate sale. Seven siblings fighting over their inheritance, and they can’t wait to unload the place. The agent says it’s a teardown, but I say no! Lick of paint!” He swivelled in his seat to greet the man on the next stool over. “Poor bastard: dead no more than five minutes,” he said. “Dirty dishes still resting in the sink.”

Sara took a step back and caught herself in the mirror behind the bar. Her hair falling out of its ponytail in wisps. She’d had to run from the bus stop, so as not to be late.

“Stop, Luke,” Fannie patted his hand. “You’re upsetting Sara. Look, you can see you’ve upset her.” She reached across the bar and pulled a cherry by its stem. “There weren’t really dishes in the sink, Sara-bear. It’s more of a turn of phrase.”

Luke leaned to the man at his side, a drama-club whisper: “The hell there weren’t. Only way I can afford it.”

Fannie rolled her eyes, then squinted a little at Sara.

“You’ve got something in your hair. Here, let me see.” She boosted up from her bar stool, beckoning. “There’s an apartment too,” she said when their faces were close together. “Sweet little place. Separate entrance and everything.” She pulled at one of Sara’s errant curls. “There, got it.” Fannie rubbed the dry petal between her fingers. “Where’d you pick that up?”

Sara turned away to add a bit of lime to Luke’s glass.

jim lay in her purse, under the bar, breathing shallow and quick now. Sara touched a finger to the cat’s belly, feeling the rise and fall of it. Her back was to the door, but she could see in the mirror where Fannie and Luke still sat, on the other side of the bar, Luke bouncing the used lime slice around in his empty glass in a cheerful way when Harding came in.

She must have stiffened or made a sound, because Fannie turned on her stool and then spun back to Sara, too fast.

“Sara. Listen to me now.”

Fannie with a hand around Luke’s wrist. The wrist whitening in her grip.

“Don’t,” Luke said. “Just don’t say a thing.”

Kitten Jim’s fur bristly and almost damp under Sara’s fingers. Harding didn’t come any closer, but stopped in the doorway. Waiting.