When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, school boards in Toronto and across the province sprang into action to ensure that every student would have access to a laptop or a tablet. More than 21,000 devices equipped with data access were distributed to families in need to accommodate the switch to remote learning. Meanwhile, in northern communities—where the internet has long been notoriously slow, expensive, and unreliable—many families didn’t have the same privilege.

“Some teachers told us they needed to deliver paper packages door-to-door to ensure students would have some worksheets and learning materials,” said Michael Furdyk, the co-founder and director of technology for TakingITGlobal, an organization focused on youth empowerment.

While 99.3 percent of urban households had access to high-quality internet in 2021, only 59.5 percent of rural households had the same connectivity, according to the Auditor General of Canada. In comparison, only 42.9 percent of First Nations on reserve had internet access.

It’s an example of what’s known as the digital divide—some Canadian students were able to simply open their laptops and resume their lessons online via video chat, while those in rural and remote communities had less access to the online world.

Even in Ontario, where telecommunication providers stepped in to help local students, their networks mostly don’t reach the northern part of the province. Moreover, according to a survey from the Diversity Institute, Indigenous people in Canada have less access to laptops and other digital devices.

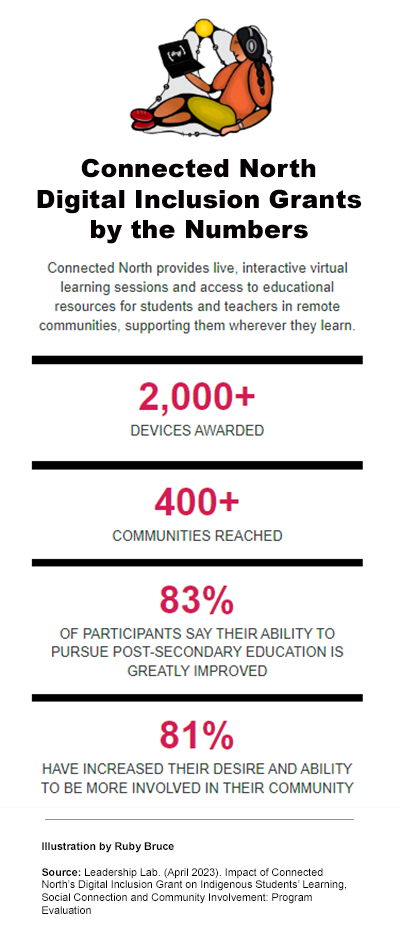

That’s why Connected North was launched ten years ago, aiming to bridge the connectivity gap between K-12 students and teachers in rural and remote Indigenous communities, and the rest of Canada. The program was founded by Cisco, and is now operated by TakingITGlobal, a registered charity.

Though Connected North began long before the COVID-19 pandemic, its work became more crucial during lockdown when schools across Canada made the switch to online learning.

“When the pandemic hit, those students that we work with were so much further off with the access to opportunities, because they didn’t have devices to send home, they didn’t have reliable Internet at home,” explained Jennifer Corriero, co-founder and executive director at TakingITGlobal .

“In very small communities, we heard reports that things were just shut down for months on end.”

In response to the increasing need for digital devices during lockdown, TakingITGlobal secured funding to launch Digital Inclusion Grants, which has so far provided approximately 2,000 laptops to Indigenous students nationally. According to Corriero, the Digital Inclusion Grants program started with Connected North high schools, and then expanded to post-secondary institutions. The brand-new computers were pre-loaded with over 100 gigabytes of video lessons, including interviews with Indigenous role models, digital skills training, and more.

In response to the increasing need for digital devices during lockdown, TakingITGlobal secured funding to launch Digital Inclusion Grants, which has so far provided approximately 2,000 laptops to Indigenous students nationally. According to Corriero, the Digital Inclusion Grants program started with Connected North high schools, and then expanded to post-secondary institutions. The brand-new computers were pre-loaded with over 100 gigabytes of video lessons, including interviews with Indigenous role models, digital skills training, and more.

“We had a digital skills program, where we were doing in-person training bringing students together. But we moved online, and hired many of Indigenous creatives involved, now over 50 of them, to develop and record their tutorials for on-demand access,” Furdyk said. The lessons include everything from a beadwork tutorial with Wet’suwet’en artist Jean Baptiste to breakdancing basics with Nipissing First Nations’ Que Rock.

As a result of this, an Indigenous student can now learn how to film, fly a drone, or launch a website all on their own from the comfort of their own device, said Furdyk.

According to a program evaluation by Toronto Metropolitan University’s Leadership Lab on the impact of Connected North’s Digital Inclusion Grants, 83 percent of students who participated said their ability to pursue post-secondary education was greatly improved as a result of the program; while 81 percent said the grants had increased their desire and ability to be more involved in their community.

A connected north

Lorenza Mautaritnaaq of Baker Lake, Nunavut, was one of the high school students who accessed the Digital Inclusion Grants. Before receiving her laptop, Mautaritnaaq didn’t have a computer at home to complete her schoolwork.

“It made it easier for me because I got my own laptop and I could do my work whenever I needed to,” Mautaritnaaq explained. “I don’t have to depend on the school or anyone else.”

Corriero emphasized that more needs to be done to support rural and remote communities to bridge the digital divide, which has to go beyond one-off programs. She explained how the demand for the Digital Inclusion Grants exceeds their ability to respond, and that they were “flooded with applications within a couple of weeks.”

Furdyk agreed, saying TakingITGlobal was able to launch the Digital Inclusion Grants with backing from Supports for Student Learning, a federal funding program created during the pandemic. But the demand clearly indicates a wider need.

While getting laptops and internet access to every rural and remote Indigenous student would require a significant investment, Furdyk feels it’s within the realm of possibility. With billions of dollars in government investments being made, he is optimistic that improved access in the coming years will reach rural and remote Indigenous communities.

Furdyk also believes that creativity is a key part of the equation since technology gives students tools to be creative, build ideas, and learn their culture. One of the things TakingITGlobal has done, along with equipping students with laptops, is connecting Indigenous elders with technology so that they can record teachings to share and deliver live video sessions from home.

“We need to prepare students to be creators of content, not just consumers,” said Furdyk in talking about the need to think more broadly about digital inclusion, not just from a hardware point of view, but from a learning and content point of view.

Corriero said she likes to think of these grants as a demonstration of what can happen with proper resourcing and initiative. She highlighted that Connected North will continue its work to bridge the digital divide for the 150 schools it serves, and most importantly, the many students who attend them.

For Mautaritnaaq, who is now 19, her laptop has stayed with her even after graduating high school in 2022. She is now pursuing post-secondary education at Nunavut Sivuniksavut, a unique program specifically for Inuit youth.

“Two weeks after I graduated high school, I moved away to Ottawa for college,” she said. “I’m studying Inuit Studies and learning about my culture.”

The program consists of learning everything, from language and Inuit history to performance arts. Mautaritnaaq was able to bring the laptop with her in order to attend online classes. She is grateful to be able to continue to utilize it for her schoolwork, especially as she is about to enter her second year at college.

“There was a lot of homework,” she said. “So it was good that I had my laptop.”

VISIT CONNECTEDNORTH.ORG FOR MORE INFO