I’m not sure why I was allowed to see the movie as many times as I did—or at all, really. My parents had strict rules about what was unacceptable for a child of seven or eight to bear witness to: specifically, video games that involved violence, reality shows that involved sex, and MTV music videos that involved both. Despite these content restrictions, it was somehow permissible for me to sit on the living room floor, my mother curled up on the couch, and have Tyler Perry’s agonized, absurdist family dramas beamed directly into my developing prefrontal cortex. I was too young to walk to the store on my own—but not too young to see Diary of a Mad Black Woman.

It was one of my mother’s favourite movies, this orgiastic portrait of a doomed and crumbling marriage. And the plot was virtually the same as that of Perry’s other movies—as it has been for the past two decades: a downtrodden, exploited Black woman is rescued from cruelty and loneliness by a simple, working-class, churchgoing Black man, with a whole lot of circus behaviour as the backdrop. There are cartoonish drug addicts and ever-sermonizing elders. There are predatory, abusive Black men and helpless, suffering Black women. There is unforgivable violence waged on hairstyles (in some films, wigs shift partway through scenes). And there’s the gun-toting, manhandling, weed-smoking Madea, played by Perry in a grey wig and floral housedress, whose lingua franca involves creative liberties with Biblical quotes. Notably, there are no people, only slapstick caricatures and miserable tropes: minstrels that don’t speak or act like anyone from the block.

I have loved these movies and hated them. I’ve considered Perry the greatest peddler of minstrel shows in our time and also laughed at the minstrel shows. I’ve appreciated his refusal to shy away from the ugly and the unsavoury and been irritated by his moralistic portrayals of ugliness and unsavouriness. Sure, the movies are often bad, unrealistic, even insulting. But I’ve never thought they were devoid of value. I’ve never felt he was trying to say this is really how it all is, that he was trying to assert some comical, monolithic model of Blackness as being constitutive of all perspectives, of all Black lives. These are one person’s ideas and psychic conflicts, and they’re ultimately real to him; he uses his writing to exorcise his own personal demons from the past, then laugh at them. I look at these stories and see a funhouse mirror, stereotypes inflated into the shapes of human beings. But whose sensibilities are we trying to flatter when we say one kind of Black story is more valuable, more real, than another?

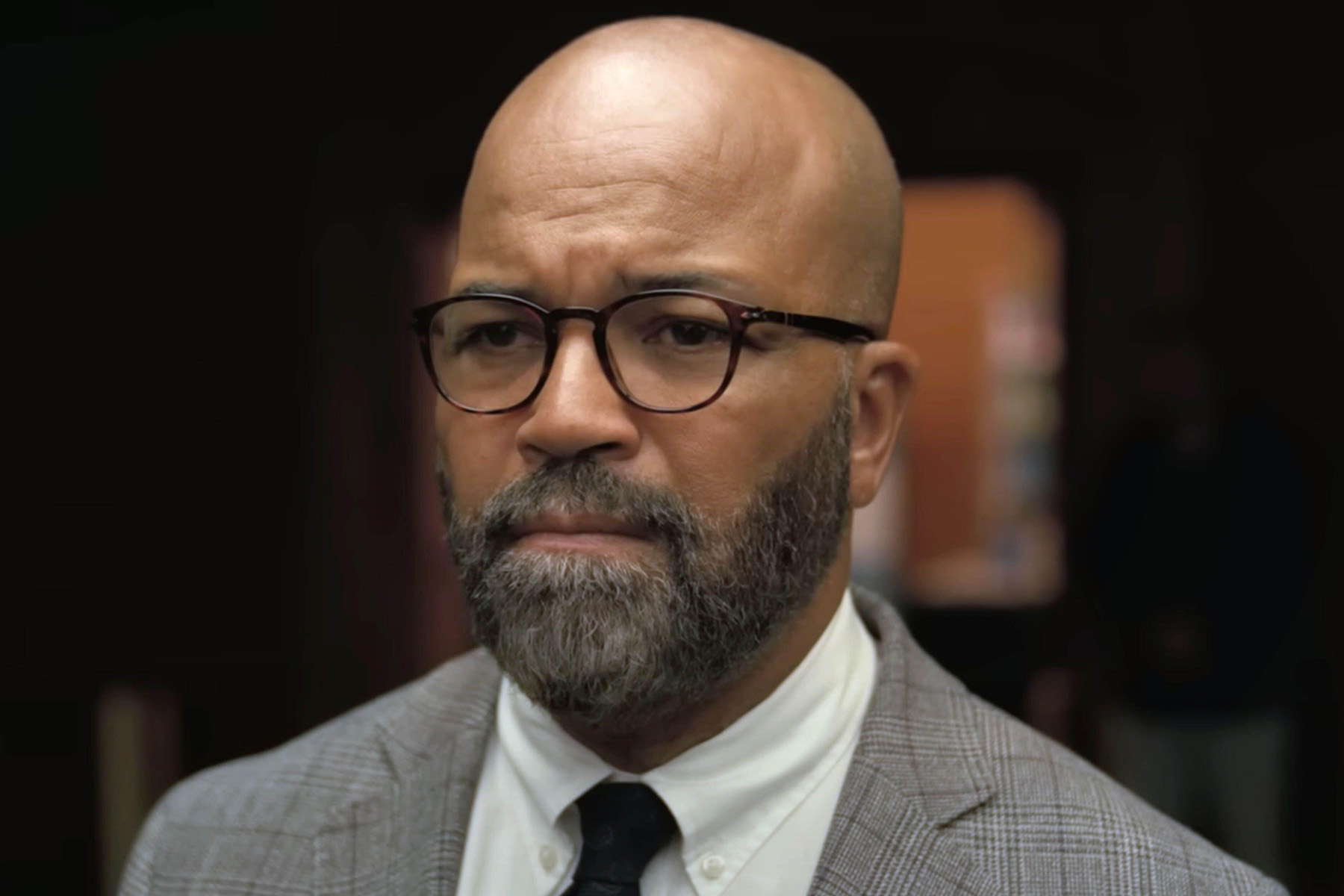

In Percival Everett’s 2001 novel Erasure, our solemn writer-academic protagonist Thelonious “Monk” Ellison is tortured by realness. Or rather, he’s tortured by white definitions of Black realness and how the gatekeepers are convinced that the gritty stories are what really sell. But why should his Blackness be measured against his ability to perform his suffering on the page? What even is an “authentic” Black voice? What does it sound like and what does it contain? Amid his existential spiral, Monk converts his disillusionment into humour, taking up a literary persona to write a parody so incontrovertibly offensive that he’s sure the publishers will rethink the minstrelsy they’ve been peddling as “necessary.” Surprise! They do not. Instead, they want to pay him $600,000 to publish My Pafology, and a couple million to adapt it into a film, and because his mother is dying and his sister is dead and he desperately needs the money, this is how Monk becomes exactly the thing he hates: a sellout.

American Fiction, Cord Jefferson’s star-studded adaptation of the novel, just won best adapted screenplay at the Oscars. Admittedly, I have my reservations about the merits of a satire when the subjects in its crosshairs uniformly adore it, and about how artificially sweetened the movie feels compared to the book. (A murder by an anti-abortion activist becomes a random heart attack; class tensions between a housekeeper and her employer are softened; white characters are rendered so cartoonishly racist that it’s unlikely any viewer would feel implicated—and does a satire work if nobody’s feelings got hurt?)

These reservations were magnified when a reporter asked Jefferson about narrowly imagined Black characters in film, and he replied like he hadn’t watched any movies by Black filmmakers in the past decade. Our storytelling, he said, “doesn’t need to take place on a plantation, doesn’t need to take place in the projects, doesn’t need to have drug dealers in it, doesn’t need to have gang members in it. There’s an audience [and a] market for depictions of Black life that are as broad and as deep as any other depictions of people’s lives.”

Two things about that statement. First, it’s difficult to recall any movie in recent memory—other than one of Perry’s—that trivialized our lives in this specific way. The past year alone brought directorial debuts like Rye Lane, A Thousand and One, Earth Mama, and All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt—each offering broad depictions of Black life that Jefferson seems to be saying we don’t get enough of. Second, his answer appears to completely miss the point of Everett’s novel and its devastating critique of white liberalism. By suggesting Huxtable-style storytelling as the more “realistic” depiction of Black life, Jefferson—along with his movie—is asserting a false dichotomy between the realness or depth of poor/working-class stories and those of the striving upper middle class.

It’s possible this is an uncharitable reading of the film. Maybe Jefferson was just working through his own frustrations with these institutions, since most of the executives he solicited to fund American Fiction turned him down and he had to make the movie very cheaply. I don’t believe he necessarily shares Monk’s bourgeois sensibility. But why this movie, now? Why these tepid shifts from the source material? Why does it feel as if the director is suggesting we desperately need to funnel more money into manicured images of Black upper-middle-class aspiration when it’s not even the experience of most Black households in America?

Everett’s intention with Erasure was not to discourage any literary inquiries into the conditions of poverty, or slavery, or incarceration. He himself says in a 1991 essay on African American literature that “the failing is not in what we show but in how it is seen” (italics mine), because “we are at the economic mercy of a market which seeks to affirm its beliefs about African-Americans.” He was attempting to question the nature of which stories in particular are deemed “authentic,” “marketable,” and “commercially viable,” and he was illuminating what it says about our culture that there’s such an insatiable demand for narratives which return to such well-trodden ground. He’s excoriating the market’s fetishistic logic, not saying we don’t still need dispatches from the outer rims of society by the most marginalized people in our culture.

American Fiction isn’t even the first piece of art in the past several years that has stood at the threshold of this problem and criticized it from the inside. R. F. Kuang’s Yellowface and Charles Yu’s Interior Chinatown both satirized this same blend of white performativity and racial pigeonholing from the perspective of Asian American authors. The marketability of Blackness in corporate publishing—and an exhaustion with the familiar, grotesque ways it is so often commodified and circulated—is likewise examined with a cool irony in a series of recent novels.

In Raven Leilani’s effervescent debut Luster, a Black woman at a publishing house attends a “Diversity Giveaway,” where she mainly finds slave narratives, plus “a domestic drama about a Black maid who, like Schrödinger’s cat, is both alive and dead.” Uwem Akpan’s picaresque New York, My Village finds multiple writers given the same extractive advice by predatory editors on how they should process their trauma: You should really write a memoir. Zakiya Dalila Harris’s The Other Black Girl, which was adapted into a TV series in 2023, is about the only Black employee at a Manhattan publishing house, who faces a crisis when a manuscript lands on her desk that features a Black character named Shartricia who, nineteen and pregnant with her fifth child, scans as “a cross between that of a freed slave and a Tyler Perry character down on her luck.”

This is far from being a new conversation. Many critics have written brilliantly about the ways Black trauma has generated its own entertainment industry, from public beatings and lynching postcards to football games, Dana Schutz’s Open Casket, and music videos restaging church shootings. These anxieties about “authentic” representations of Blackness are as old as those representations themselves, and literature has for decades been fertile ground for that genre of discussion.

In a famous essay from 1926, Langston Hughes argued for the importance of writing about “the low-down folks, the so-called common element,” who “do not particularly care whether they are like white folks or anybody else.” Richard Wright, whose Native Son is parodied by Monk’s My Pafology, complained that Zora Neale Hurston was using “minstrel techniques” to titillate the white readers of Their Eyes Were Watching God, because she wrote about love and sex in a time when both were de-emphasized by Black novelists who thought it more urgent to address race. Eldridge Cleaver said James Baldwin was anti-Black (and wanted to be white) because he sometimes wrote gay and bisexual characters. Baldwin (and Ralph Ellison) committed literary patricide by saying that Native Son, written by his mentor, was closer to a “pamphlet” made to shock white people than it was to actual art. And Spike Lee famously derided Tyler Perry’s whole oeuvre (stage plays, TV shows, movies) as “coonery buffoonery.”

Where racist propaganda is in vogue, obsession over the imprimatur of “realness” is almost inevitable. It’s still true that minstrel shows birthed the whole of American popular culture and that the history of Black representation in art is disfigured by constant dehumanization. This apprehensiveness has characterized no shortage of criticism about early hip-hop music as minstrelsy, about “street literature” as minstrelsy, about slave movies as minstrelsy. In our race-obsessed culture, authenticity is the artist’s disquieted ideal, fakeness the most pejorative charge. Black artists are most often praised for the “realness” and “visceral nature” of their work, in part because Black art is almost always read in this way: not as art but as transcription. The Black novelist is assumed to be writing “autobiographical fiction” (as opposed to the more literary “autofiction”). The Black visual artist is expected to meditate on Black ideas. Rap lyrics about crime, imagined or not, are admitted in court proceedings as evidence of the author’s actual criminality, despite no other fictionalized artform under the sun being treated this way. There’s a cultural overdetermination of “Black authenticity” and a refusal to admit that it doesn’t really exist in the way we’ve convinced ourselves that it does.

The problem is not really the art, despite what Jefferson’s movie unwittingly suggests. The real culprit is the market and how Black artists are so often recruited only to point to where it hurts, to confirm certain beliefs about their identities, and nothing more. Brandon Taylor’s The Late Americans features a jaded poet in a writing workshop who is terminally bored of his generation’s trauma exhibitionism and frustrated by the overwrought language used to praise their tales of personal agony: “raw,” “real,” “visceral.” The reason Monk finds himself at the end of his rope is that editors are totally disinterested in his dense, obscure fictions, not only because they’re heady and inaccessible—his latest, rejected by seventeen publishers, features Aristophanes and Euripides killing a younger dramatist—but because they contain no misery, no pain. “‘The line is, you’re not black enough,’” his agent says.

Apparently (at least, according to the predominantly white people who keep watch at the gates of the publishing world), Blackness and abjection are coterminous. The publishers want something gritty, something real: something like the runaway bestseller We’s Lives in Da Ghetto, a slice-of-life fiction written by a Black woman after a few days spent in Harlem, praised in The Atlantic Monthly for its “haunting verisimilitude.”

Monk finds it cheaply offensive, “like strolling through an antique mall, feeling good, liking the sunny day and then turning the corner to find a display of watermelon-eating, banjo-playing darkie carvings and a pyramid of Mammy cookie jars.” The reviewers, naturally, find it masterful.