In August 2015, Dan Kneeshaw was surveying cutblocks in the forest north of the St. Lawrence, in the Côte-Nord region, about 670 kilometres northeast of Montreal. For the first time in recorded history, the area is an epicentre for an outbreak of the spruce budworm, a caterpillar that eats the new shoots of certain species of evergreens, and, over a period of five to ten years, slowly starves them of their ability to turn sunlight into energy. The trees turn amber every summer, as though they are being strangled, and then grey as they die.

The previous year, the budworm’s numbers had skyrocketed to the point that they spilled out of the mature fir they prefer—the cone-shaped evergreens usually used for Christmas trees—and advanced on the trees all around. It redoubled its attack on black and white spruce, then moved on to larch and pine. Even seedlings were hung with silk threads as the caterpillars dropped from branch to branch, eating, then spinning a type of cocoon around themselves, preparing to transform into moths. There were so many moths in the area that during their migrations across the St. Lawrence over the years, the swarms appeared on the weather radar as a light rain. On the south shore, more fir began to turn amber.

The first cutblock that Kneeshaw hiked into should have been logged with two goals in mind: limiting the forest’s vulnerability to the infestation by reducing concentrations of fir trees, the budworm’s preferred food, and harvesting the wood before the trees died and their timber was damaged or unusable.

Viewing it from a distance, Kneeshaw was impressed. The loggers had left many tall trees and saplings behind, creating the conditions needed for the forest to maintain a significant canopy, with gaps letting in sunlight here and there, encouraging a diversity of structures: trees of varying ages and sizes, from seedlings to venerable stands hundreds of years old. A diverse forest provides forage and shelter for birds and mammals, woodpeckers and martens and caribou, and is more likely to support the species needed to fight off attacks by funguses and parasites or to regenerate after a catastrophe such as a windstorm.

But as Kneeshaw drew closer, he realized that many of the tall trees were infested fir and that many of the stumps were black spruce—more resilient, budworm-resistant trees whose timber and chips fetch a higher price. Those fir that remained were infested, but not dead yet. In essence, the area had been made to order for the budworm, like tinder piled before a wildfire.

He was angry. Because his work involves teaching students to understand cutblock designs, he could see where this one had been subverted. “It was deeply disturbing,” he said. “To initial appearances, it seemed like a really nice thing, but when I looked at it in more depth, I could see that short-term financial rewards were overshadowing good forestry.”

Kneeshaw spent the day driving along the logging roads, tracking the budworm. The designs he saw, which had been prepared by forestry ministry engineers, worried him, as he felt that they would increase fir growth at the expense of other species, creating a sea of fir susceptible to the budworm in the areas hit hardest. The next infestation would likely burn through them unhindered, unstoppable.

Cutting healthy trees may help the companies operating in the infested areas maintain profits, and including them in cutblocks with infested trees helps to ensure that the government does not lose the royalties companies pay for the timber they harvest on public lands. But such decisions endanger the forest’s—and the industry’s—long-term health. A similar situation was seen in British Columbia during the pine-beetle outbreak that began in the ’90s and is still petering out, killing off millions of hectares of lodgepole pine and devastating some small logging towns.

“Government and industry should be making decisions for the next generation,” Kneeshaw said. “If we have people doing the opposite, then these communities will be in jeopardy.”

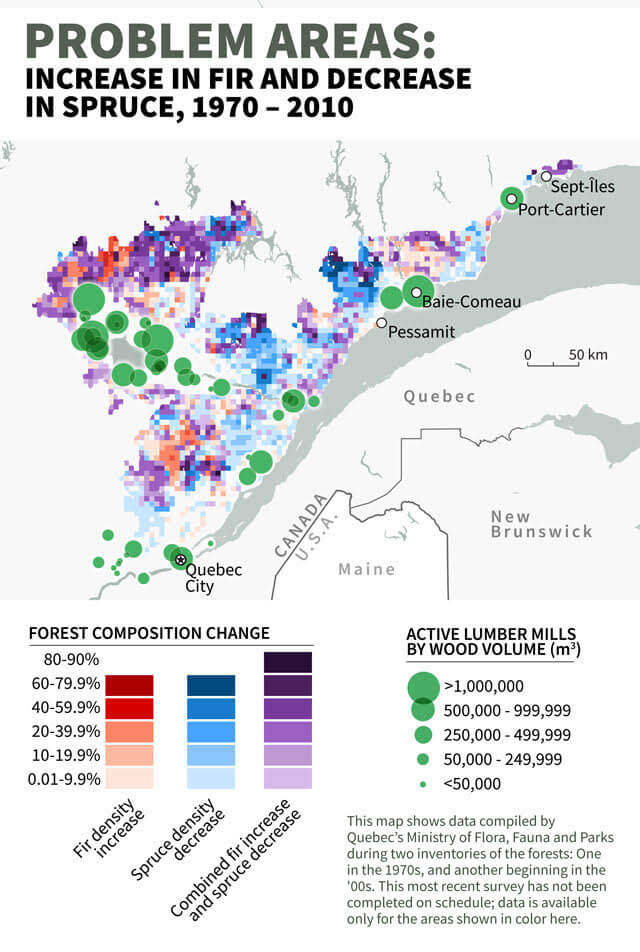

The forests of the Côte-Nord have been changing. The shady, undisturbed spruce forests that caribou favour have been ceding to shrubbier fir forests where moose browse. The switch in species has happened over decades, so slowly that the differences are nearly imperceptible to humans; Innu hunters, though, whose ancestral territory encompasses this area, point out that the caribou no longer forage near the shore, but have been pushed into the north.

It started in the ’30s, when the Chicago-based Tribune Company built the town of Baie-Comeau and its mill beside the St. Lawrence to log spruce to make newsprint—in the Côte-Nord, fir seedlings lurk on the forest floor, waiting to shoot up quickly when a black spruce tree falls, so fir tends to replace spruce after logging.

Fir wasn’t as valued by the loggers, because, as a consequence of its fast growth, the timber is weaker. It is the sick man of the forest, susceptible to almost all diseases, fungi, and insects; it ages prematurely in comparison to other evergreens.

Evidence suggests that by the ’70s, the number of fir had increased in the area being logged. Québécois foresters have a term for this switch: ensapinage, or “fir tree invasion.” The ensapinage slowly continued, cutblock by cutblock. Climate change sped up the process, according to Yves Bergeron, a professor of forest ecology and management at the University of Quebec at Abitibi-Témiscamingue and UQAM.

The budworm was known to loggers and foresters even then; it was the forest’s gardener, returning every thirty-five years to kill off sickly and dying fir trees, making room for slow-growing black spruce. But in the ’70 and ’80s, an infestation took hold across the eastern provinces and in the northeastern United States on a scale never seen before, damaging and killing trees across nearly 58 million hectares, resulting in the loss of about 500 million cubic metres of timber and costing some $12.5 billion in Quebec alone.

As stands of trees turned amber and then grey, provincial governments across the country sprayed the forests with insecticides. Fenitrothion, the chemical used in New Brunswick, had been linked to an outbreak of Reye’s syndrome, a metabolic disorder that causes swelling in the liver and the brain. Despite petitions, the province’s minister of natural resources, Roland Boudreau, continued to order the spraying, even as the budworm continued its march. (The insecticide was later banned.) The losses were staggering—71 percent of Cape Breton Island’s merchantable timber was destroyed, according to researchers at Mount Allison University.

Thinking back over what he’d seen north of Baie-Comeau, Kneeshaw decided to investigate how salvage logging had been carried out during the ’70s and ’80s. He asked American and Canadian researchers from the university system and from the provincial and federal forestry ministries to join him in a study of cuts from that era in Quebec’s history.

In theory, management of a budworm outbreak is intended to work something like a vaccination effort. The forestry ministry recommends that loggers focus on cutting the most vulnerable trees, which in the Côte-Nord are the fir. While the budworm does attack black spruce, most of the trees survive. When the fir trees are surrounded by more resilient species such as the black spruce, as they are in a virgin forest, the budworms have more trouble finding food. The population remains low and may even peter out.

Kneeshaw’s group discovered that the forestry companies operating during the last budworm outbreak often focused on harvesting black spruce instead. This reduced the ecosystem’s resilience, because after those cuts, fir would grow back.

According to the data, there were sporadic instances in the ’70s and ’80s when only black spruce, the most valuable trees, were harvested and the fir left behind—teams of loggers were quietly dipping into the till, further pushing the most vulnerable areas of the forest toward fir growth. “Like we see in riots or stuff after hockey games, there’s always a few people that are taking advantage of the situation,” Kneeshaw said.

It’s this preference for the healthier trees instead of the dying ones that worries Kneeshaw—especially now that the budworm has infested seven million hectares. “We know as things go along, people panic,” he said. “If we get up to 30 million hectares being defoliated, there’s going to be all sorts of pressure on the government.”

How should a community respond to a mass die-off in its forests? During the pine-beetle infestation in BC, the opinions ranged from allowing nature to take its course, to harvesting almost all the lodgepole pine, wherever they were. In the aftermath, thousands of workers lost their jobs as mills were shut down, and several communities are now struggling to survive. Finding consensus means thinking about how our lives will be different when those trees are gone.

They thought they were prepared. A network of researchers at universities across Quebec had been studying the budworm for decades. A great deal had been learned since the last outbreak, after it began to decline in the ’80s; much of its life cycle and long relationship with the fir were understood.

In 2006, when the budworm started attacking the fir in the Mistassini Lake area, a notch among the craggy hillsides and lakes just north of Baie-Comeau, population 22,000, the forestry engineers and other workers at first saw it as just one more problem to solve.

“With my years of experience, I took it as a challenge,” said Jacques Duval, the forestry engineer for the Ministère des Forêts, de la Faune et des Parcs (MFFP) who has designed many of the cutblocks during the infestation, starting in 2008. The MFFP’s regional office is on Baie-Comeau’s main strip, a low building among the fast-food restaurants. From there, more than twenty people supervise an area about the same size as Israel. Duval worked in the industry during the previous budworm outbreak, and at the beginning, he said, he wasn’t concerned that this would affect jobs—the budworm could be managed.

But the budworm spread north from that valley, along the rivers that flow into the St. Lawrence, draining the land like a tilted board, and attacked the forest. The fury of the infestation that followed was unprecedented in the Côte-Nord, which became an epicentre from which the moths flew out and infected other regions.

The troubles for the MFFP began in 2010, when Resolute Forest Products, the company operating in the most affected area, complained about cutblocks that would have them remove the fir trees from the budworm’s path. Resolute didn’t need much fir—the recipe at the paper plant is about 70 to 75 percent spruce, and fir timber fetches a lower price. But the manager of forestry operations in Côte-Nord, Denis Villeneuve, a practical man with thirty years’ experience, had no choice but to do what MFFP had asked, which involved the expense of relocating crews and equipment from the virgin black spruce forests in the north.

The government couldn’t just lose the royalties that the forestry companies would have paid for the timber of those fir trees, which were starving and dying where they stood. The Société de Protection des Forêts Contre les Insectes et Maladies (SOPFIM), a ministry- and industry-funded non-profit that combats insect infestations, tried to buy the MFFP some time, sending out Cessnas, Air Tractors, and other small agricultural planes from the airstrip south of the city. They burred out over the hills to drop on carefully designated targets a solution containing an organism lethal to the budworm, trying to keep the trees alive until they could be cut. “It allowed me to delay in places we couldn’t harvest yet,” Duval said.

But by 2011, after six seasons of losing their foliage, the trees began dying of starvation. Some of the logs that arrived at the sawmill were dried out, a few dead, green with fungus and riddled with beetle holes. Processing them cost Resolute money, and the company balked at taking any more wood from the infested trees.

In his office close to the mill, Villeneuve said that the situation was almost financially impossible. “The lumber products we produce will have a lower value,” he explained. “An orange two-by-four is not sellable.” Resolute and Arbec Forest Products, another company operating in the area, started demanding that the government accept lower royalties for the wood.

The forest isn’t the only area that Duval and his colleagues must safeguard: Quebec law also makes them the guardians of their region’s industry, and it’s the paper plant that first anchored Baie-Comeau to the shore of the St. Lawrence. The forest meets the sea at the town’s deep, brackish port, which ships paper and ore from the interior to other continents. About 4,400 jobs in the region now depend on forestry, and some families have worked at the plant or in the forest for generations.

There are only a handful of other big employers. The nearest small city is a couple of hours’ drive away; there is little besides the almost limitless expanse of trees, with its hydroelectric plants, mines, and forestry.

Adding to the pressures on the MFFP workers, the forest industry in the Baie-Comeau area has grown more precarious. For decades, the forestry companies have been forced to work further and further north from the town, chasing the virgin forests for their slow-growing spruce. Villeneuve estimated that nearer to the sawmill, the forest was nearly half fir now, and ministry data show that black spruce in that area has fallen below 10 percent. After the dramatic fall in the demand for paper over the past decade, the costs of the long drive from the virgin forest to the shore are a handicap.

The MFFP’s regional offices have a great deal of autonomy—they have the latitude that they need to adapt the provincial government’s instructions to local ecosystems in times of crisis, such as a budworm infestation. When engineers are designing pre-salvage and salvage cuts, they are instructed to consider economic conditions.

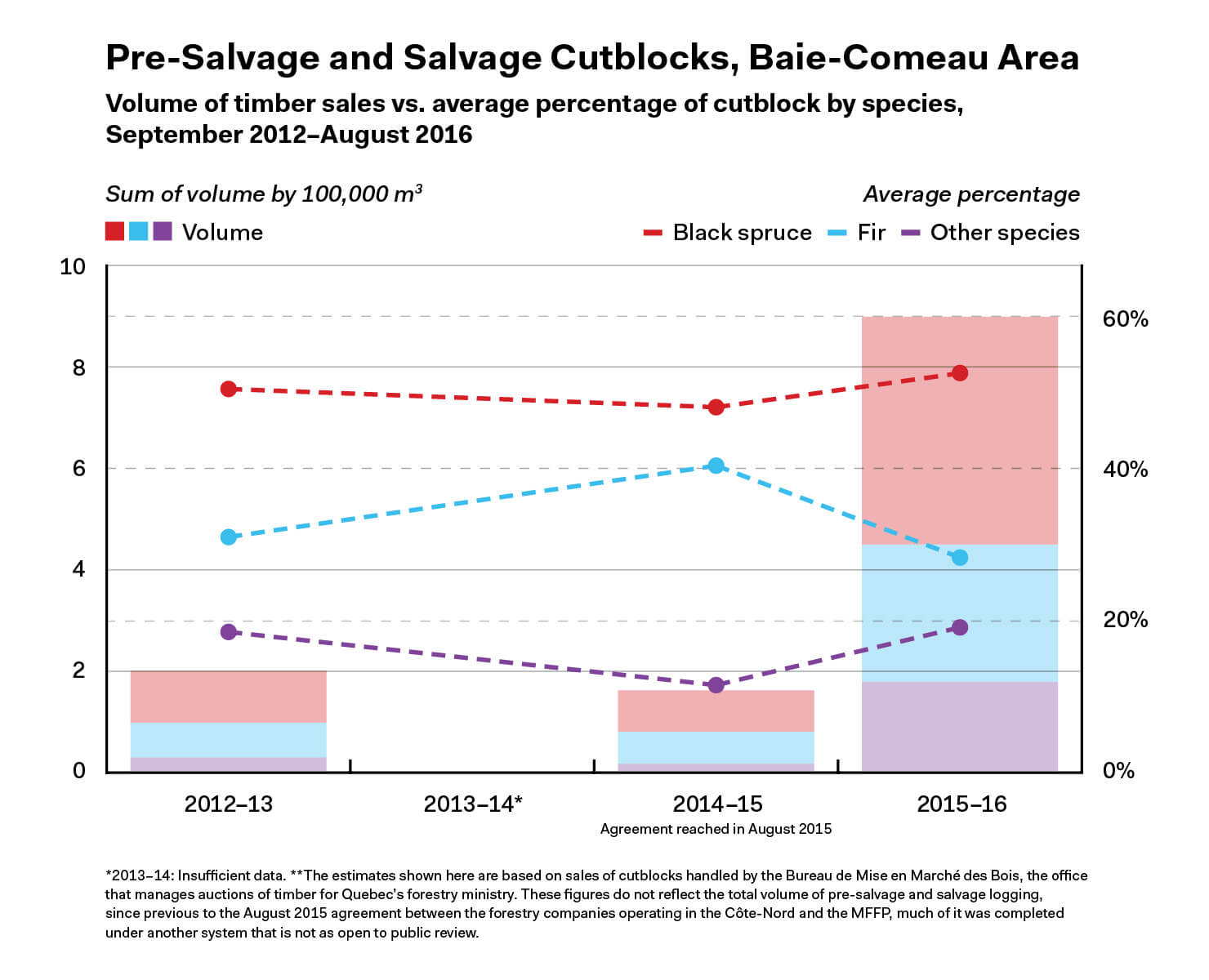

In Baie-Comeau, sales data for rights to cut timber on the infested cutblocks reveal that some of the ministry’s guidelines were set aside. The ministry’s manual for foresters instructs them to focus logging on the starving and dying trees in infested areas, and forestry ministry experts recommend that about two-thirds of the trees on such a cutblock should be damaged and dying. But for the most part, the logging appears to have focused on the healthier black spruce trees, with the infested fir included in far smaller numbers. As a technician at the Baie-Comeau office explained, “The spruce are the carrots.”

By 2014, the infestation had grown so intense north of Baie-Comeau that the ministry cut the number of trees planted nearly in half compared to 2012, afraid that the budworm would eat the seedlings. Silviculture workers—the people who replant the cutblocks with seedlings and trim back the bushes and unwanted trees—lost their jobs. Rémy Paquet, the co-owner of Nord-Forêt, said that he had to lay off twenty to twenty-five silviculture employees, most of whom had worked with his company for many years.

Then Resolute sent a shudder through the community on November 30, 2014, when—unhappy with the drop in profits—the company shut down one of its three paper-making machines at the plant for good and threatened to shut another. With this move, it had played one of its aces, showing the government the pain that closing the plant would cause the community.

The next day, 400 people demonstrated in support of Resolute and the industry, and businesses shut their doors for an hour in a show of support. Michael Cosgrove, an administrator of the local chamber of commerce, said that if the plant were shut down altogether, all three forestry companies would shut down for lack of profit, and the forestry industry in Baie-Comeau would come to an end. Businesses suffered as people began to stay home instead of going out to eat or shop, saving money in case the forestry jobs came to an end.

Others thought Resolute’s move was just theatre. The company had invested millions in its paper mill a couple of years before.

“We thought the whole time that it was a game that Resolute was playing with the government for concessions,” said Pierre Richard, the leader of the paper-mill union at the time, describing the companies’ efforts to pressure the government for financial support. “This should’ve been handled through negotiations with the government, without taking workers as hostages. They profited from the situation to get the biggest subsidy they could.”

Richard said that what the company wanted was unclear, though to satisfy the leadership, his union organized demonstrations when it was asked. “These demonstrations worried the workers and the population. I think it was useless. We did not need to go so far.”

For the people of Baie-Comeau, the uncertainty could only have been painful; it would be a hard place to leave. Perhaps because of its remoteness, the small city has a remarkable, proud self-sufficiency: it has a lively newspaper, Le Manic; seemingly countless clubs and civic organizations; and a microbrewery.

On June 16, 2015, as a deadline for the negotiations approached, logging truckers blocked traffic into town; three days later, nearly 150 people held a demonstration in support of Arbec, Boisaco, and Resolute. Both actions received attention across the province.

Four days later, Resolute and Arbec shut down logging operations. “It was sudden. We hadn’t known,” said Pascal Gauthier, a lumberjack who employs twelve others through his company Entreprises Forestières J&J Tanguay. “We had just emptied our bank accounts to make repairs [on equipment] for the coming season, and then we got that bad news.” He and logger entrepreneurs like him who work on contracts have loans on more than a million dollars’ worth of machinery and try to stay ahead of the enormous monthly payments by working through the night during the workweek. One of his loggers, sitting in the cab of a feller-buncher—which looks like an excavator with a combination claw and saw—will cut and strip about 4,500 trees per ten-hour shift, he said. The forestry companies tried to find work for them elsewhere, but still, the interruption was hard.

With the work in the forest at a standstill, Resolute sent lay-off notices to the workers at the sawmill and the paper plant. Though Richard felt the company was bluffing, the government was in a bind. “The price of the raw iron has fallen apart, so this is an area that was solidly hit in the last few years economically,” said Charles-André Préfontaine, Villeneuve’s supervisor, referring to the region’s iron mines, which are another important employer. “Losing this other pillar, which is the forestry industry, that would be a disaster for the Côte-Nord.”

It was obvious that the forestry companies would get what they wanted—the question was how much the government would give them. Quebec’s Plan Nord, an initiative that would encourage private investment in the area’s resources was just getting started, and Resolute had shut down one mill and a few machines over the past few years elsewhere in the province.

On August 31, 2015, a press release from Jacques Daoust, the minister of the economy, innovation, and exports; Laurent Lessard, the minister of forests, wildlife, and parks; and Pierre Arcand, the minister responsible for the Plan Nord and for the region of the Côte-Nord, announced that an agreement had been reached that included twenty-three measures intended to support the three companies operating in the region. The terms of the deal—what the Quebec government had agreed to and how much it would cost—weren’t made public.

In Baie-Comeau, after the August 31 agreement was signed, the community sighed with relief. A headline in Le Manic read, “Finally Settled!” Life seemed to return to normal.

Arbec, Boisaco, and Resolute were happy. They now paid the government what they considered a fair price for the infested trees. Karl Blackburn, a spokesman for Resolute, summed up the result: “If we were able to sign an agreement to save the industry, with the government, it happened because all the region spoke with one voice. We were a success because we worked together.”

It’s impossible to know whether paper-mill union leader Richard and other observers were correct in their assessment that the government had been strong-armed. The forestry ministry denied an access-to-information request from The Walrus on the grounds that it would reveal the terms of a contract involving commerce. A second request was also denied.

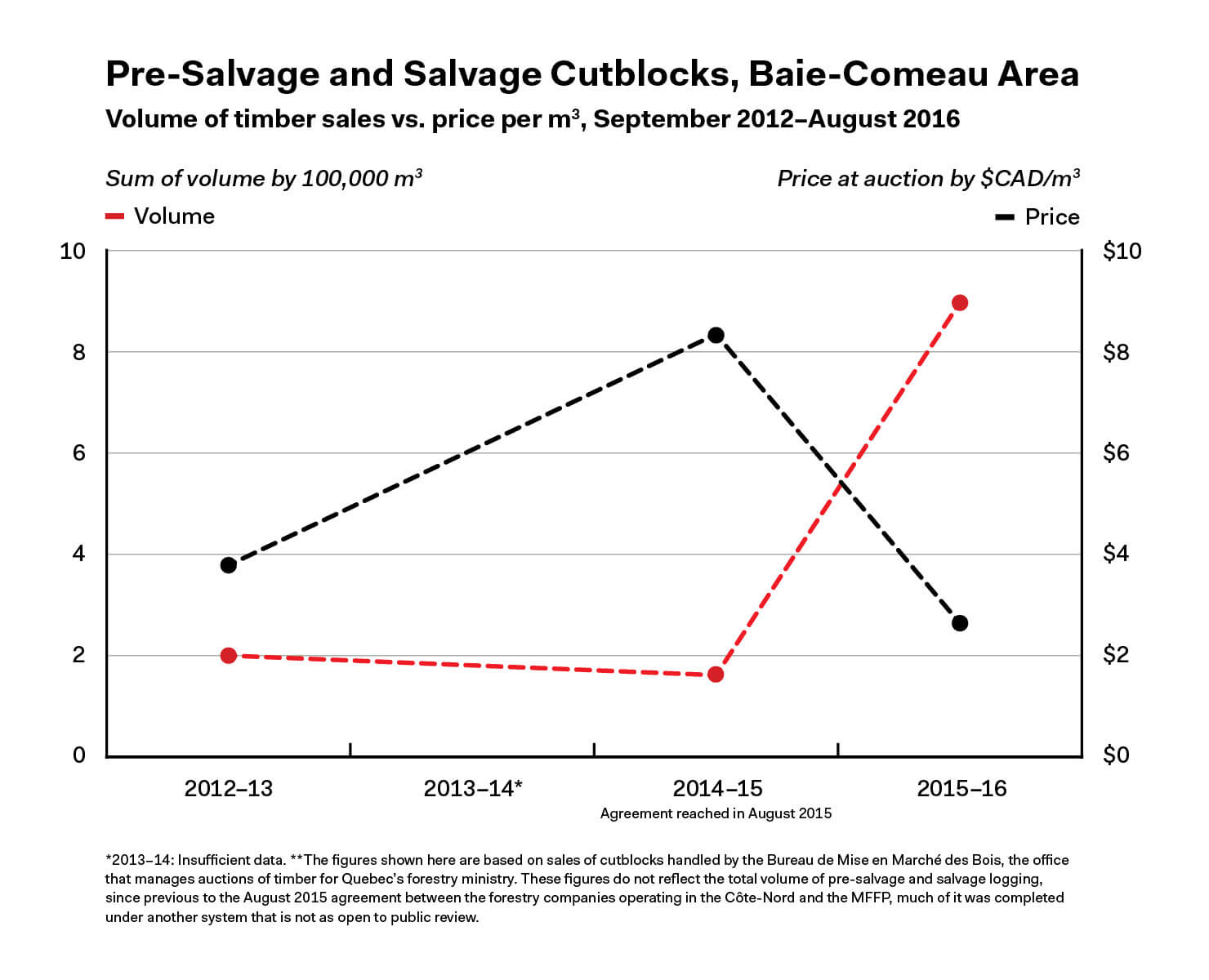

Here’s what we do know: in the three months after the deal was reached, there was a huge sell-off of black spruce in the infested areas north of Baie-Comeau, where fir is dominant—this according to sales-auctions data for the rights to cut that timber. These healthier black spruce, which constitute less than 10 percent of the forest, are needed to improve the forest’s resilience. They slow the spread of the budworm, and, for the most part, survive while the fir trees are killed off.

We also know that after the agreement, the average proportion of infested fir trees on those cutblocks fell. In effect, salvaging the infested timber was no longer a concern; instead, the forestry companies were allowed to harvest what brought the most profit: the healthy black spruce.

The companies paid the government through an auctioning system for the right to harvest that timber. Adding insult to injury for taxpayers, the total amount in the year that followed was $3 million to $5 million less than it had been prior to the agreement. This decline was seen across the Côte-Nord region, and does not include the other forms of financial aid and assistance provided to the forestry companies under the agreement.

In a situation where we should be focusing on improving the forest’s resilience in expectation of the next budworm outbreak and planning for the future of the forestry industry, it appears that the companies were permitted to cut many of the remaining stands of healthier black spruce trees in and around the most infested areas, when only a few were left. Since fir is likely to replace the black spruce when the next infestation hits, the forest will have even more fir, meaning that it will be hit harder and that the losses to the industry will be worse.

At least one member of the forestry ministry’s office was discouraged and angry, according to an internal email that was shared with The Walrus. He wrote that the budworm is just an excuse for the ministry to give money to the forestry companies. Social policy is taking precedence over ecology.

Kneeshaw argued that the ecological price the community paid was too high—healthy trees were cut in the areas where the ecosystem was most vulnerable—and that taxpayers had gotten little in return. Shown a map of these cutblocks, he felt that the local MFFP office had blatantly disregarded the guidelines. He wrote, “The pattern is exactly what I would expect for an ordinary harvest operation. Salvage logging should be in the heavily infested areas, but they’re doing the opposite.”

A year after the announcement, paper-mill union leader Richard felt that the deal had benefited only the companies’ profit margins, failing to bring investment or changes that would support the industry and its workers in the long term. “What have the taxpayers gained in exchange for reduced royalties?” he wondered. “If there are benefits, we haven’t seen any.” When asked about increased stability or certainty, Richard replied, “There’s no difference. Nothing has changed in the daily lives of the workers or the taxpayers in the region.”

One solution would be to dramatically increase tree planting in the area, but that’s unlikely to happen. The forestry ministry doesn’t do much tree planting after an area is logged, partly because “natural” regeneration is considered more natural—an estimated 15 percent of the total harvested area in the Côte-Nord is replanted each year. This often means fir will increase, especially in the south.

Paquet, frustrated, wishes that his silviculture crews could be put to work. He advocated for an aggressive approach to the fir problem, and the budworm that munches on it, in the Côte-Nord and elsewhere. “We could be doing what’s called a conversion [of the cutblocks],” Paquet explained. “That means that we’d try to diminish the level of fir and increase the percentage of spruce.” He continued, “There is no mill that will complain that there are more spruce trees and less fir, that’s for sure.” But budget limitations alone would probably make such a labour-intensive strategy impossible to implement.

The people and companies in Baie-Comeau made the choices they felt they had to make in order to keep their community, its economy, and their businesses going. But for how long, and at what price?

“This is a symptom of the first economic impacts of climate change,” said Louis Bélanger, who teaches forest management at the Université Laval in Quebec City. Representing the environmental group Nature Québec, he explained, “It’s these new insect outbreaks that [are coming into] effect. Are we capable of adapting to this, or are we, because of the economic constraints, just running faster to dilapidate what’s left of the forest?”

This past summer, the budworm migrated south and east from the Côte-Nord and Gaspésie areas. In Campbellton and Dalhousie, New Brunswick, the swarm was so thick that at night the moths swirled around the streetlights in dark blizzards. Some 400 kilometres to the southeast, in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, a biologist reported finding a few on his front porch. Other swarms appear to be moving toward Maine, where woodlot owners have begun discussing plans to cut trees before they can be affected. New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Maine have launched programs asking people to set up moth traps in their yards so that the numbers can be monitored.

A budworm colloquium at UQAM’s Acfas congress in the spring brought together ecologists, entomologists, and other forestry researchers from across Quebec and the eastern provinces. As they discussed the outbreak, there was an uncharacteristic uncertainty around questions of how far this infestation will spread, how intense it will be, and how much damage it will cause, since the conditions in forests across the continent have become unpredictable as a result of climate change.

The changes in temperature are reflected in the budworm’s current odd behaviour. Ordinarily, several years after an infestation is established, the swarms move from south to north in search of food—but this time, the budworm is going south. As higher temperatures risk making the climate drier in coming years in Quebec, the fir could be drought-stricken and defenceless in face of the waves of new diseases and insects that will move north with the change in climate.

During a warming period 6,000 years ago, the budworm ate more black spruce than in present times. Kneeshaw and some of his colleagues have also theorized that the warmer springs may prompt it to switch back to its ancient diet and then sweep west across the boreal toward the Yukon, leaving dead forests in its wake. That’s a worst-case scenario, but it helps us to understand the researchers’ nightmares: when conditions are changing, insects can adapt quickly, and the budworm is only one of many tree-killing insects that are on the move.

About five years ago, the pine beetle crossed the BC Rockies and moved east for the first time. Since its preferred host tree, the lodgepole pine, isn’t as available in Alberta or Saskatchewan, it has been attacking defenceless Jack pine—a behaviour never seen before. Academics also worry about the emerald ash borer in Ontario and Quebec and the hemlock looper, which kills conifers from Newfoundland to Alberta.

Pierre Bernier, a federal research scientist based in Quebec City, explained, “We have fire; we have insects; we have drought. The three horsemen of this apocalypse combined can create probably a more rapid shift from the closed canopy forest to a more open forest, or maybe to prairie conditions in some of those areas where currently you have forest.”

The best solution that Bernier and other researchers can suggest is that foresters in Quebec and elsewhere in Canada maintain and increase diversity: if one species of conifer is susceptible to one infestation or disease, we can only try to ensure that some of its neighbours are not.

Over the past few decades, Quebec’s forestry ministry attempted to follow this plan, directing workers to break up stands of fir in the decades before the current infestation began, and some regions have paid more attention to this than others. The harvest of healthier black spruce trees rather than infested fir in the forests of the Côte-Nord, Bélanger said, shows that the forestry industry and Canadian communities are not yet prepared to handle the political pressures involved.

“Our whole economic basis is really in jeopardy,” he said. “We should develop mechanisms to be able to better adapt to these new phenomena. We still treat these [infestations] a bit like exceptions, when this is becoming a systematic thing that we will always have to adapt [to].”

This past spring, on a trip to the cutblocks he’d described, Kneeshaw was talkative, chatting about the work done on Quebec’s ecosystems by his colleagues at UQAM. As we sped along, the valleys unfolded like origami to reveal summer cottages, each beside its own private lake. A group of teenage boys pushed their swimming rafts onto a river. A hundred kilometres into the forest, when we left the paved road and began to explore the cutblocks, men operating harvesters and other heavy machinery were cutting trees. Some had bare branches, a sign of infestation.

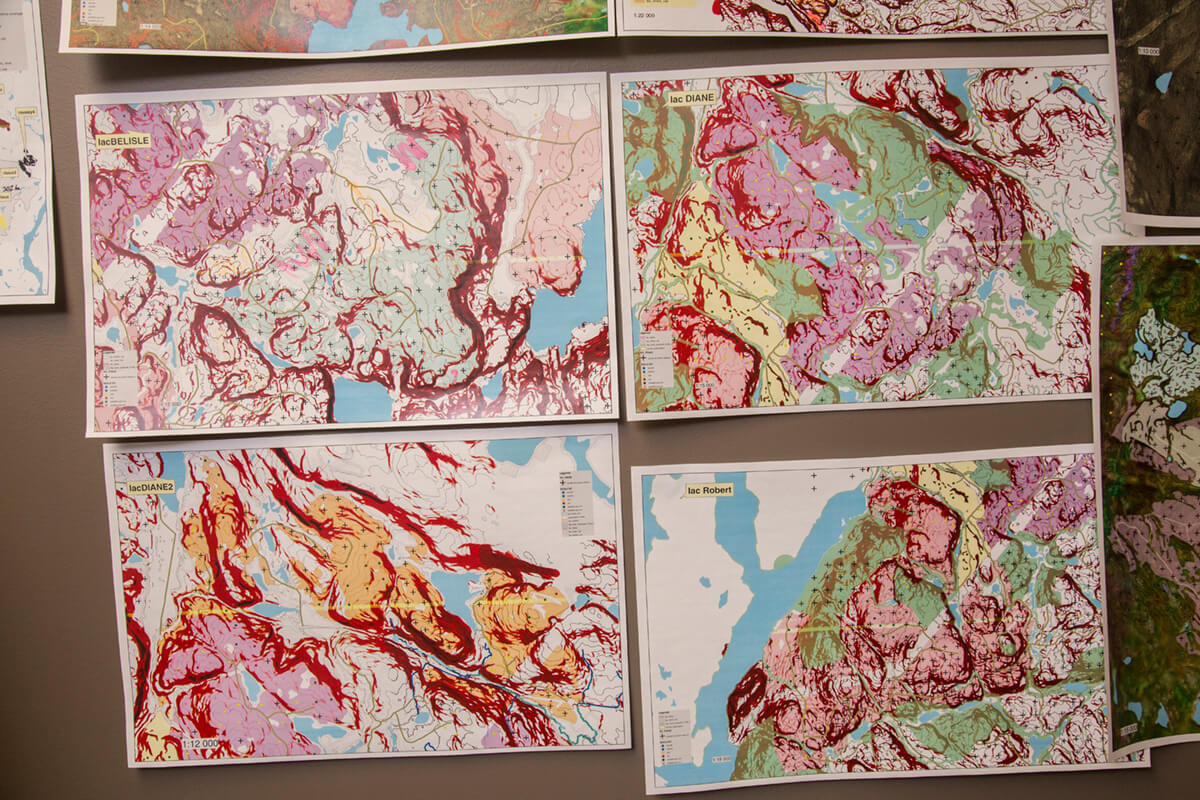

The cutblocks, which resemble chaotic blueprints, are labyrinthine in their complexity. Engineers at MFFP and at the logging companies direct loggers to target older stands in specific areas, leaving younger stands untouched. The air had the tang of freshly split wood, torn moss, and damp soil drying in the sun.

Kneeshaw surveyed five cutblocks in the infested areas. These were officially designated by the forestry ministry as falling under the guidelines in place during a budworm outbreak, when fir should be the focus of the logging. Four of them, he said, would probably be dominated by fir in the future, and thus more vulnerable to the budworm.

One site, fairly close to Baie-Comeau, was dominated by black spruce. According to Kneeshaw, the spruce trees were only approaching maturity. He suggested that they had been added to the cutblock’s design simply to make it more appealing to foresters who would be bidding for the timber.

We visited the cutblock that had first angered Kneeshaw. The big black spruce trees alongside the skidder path were indeed gone—often the harvester had reached a couple of metres into the forest, leaving a lone black spruce stump amid infested fir. “That’s what they need to run the mills, but ecologically, in the long term, it’s the wrong approach,” he remarked.

“The cumulative effect is a problem,” he wrote in a report we gave to two forestry researchers to review. “We are repeating the mistakes of the last outbreak, despite the precautions the MFFP has tried to take, and the effect will be to increase the forest’s susceptibility to the budworm.” The researchers, who were chosen partly because they tend to disagree with Kneeshaw, concurred with his assessment. (Since they work with the provincial and national forestry ministries, the reviewers requested anonymity.)

The forestry ministry didn’t directly counter Kneeshaw’s criticisms or the other data in this article. In its official response, the MFFP agreed that the cutblock described at the beginning of this article had been logged improperly—an experiment was being carried out there—and that the design hadn’t been followed. It maintained that general conditions on the ground were variable and changing over time and that the fir trees were dispersed over a large area, which posed operational difficulties.

Kneeshaw and one of the researchers felt that the answers were evasive. “If there is no, or little, fir in the landscape,” Kneeshaw wrote, “then the budworm is not a problem. If there is some, but it’s inaccessible or patchy, then it can’t be saved, and there is no need for salvage logging.”

There is no way of determining precisely how much of the Côte-Nord’s forests is now more susceptible to the budworm, but the data suggest that ministry teams elsewhere in Quebec seem to be facing pressures similar to those in Baie-Comeau—which involve including healthier trees in the infested cutblocks, even though the ecosystem will be less resilient when it’s hit by the next outbreak—and making similar choices. In the Lac Saint-Jean area, one of the major timber-producing regions, sales of timber from the most infested areas indicate that more healthy trees than vulnerable ones are being logged. In contrast, in the Sept-Îles region, to the east of Baie-Comeau, the pre-salvage and salvage cutblocks appear to focus more on the infested and sickly fir. While there are differences in each region’s ecosystem, this variation may also reflect individual decisions, as the forestry ministry’s offices try to support local industry while coping with the budworm.

Because little information is available, it’s impossible to calculate the future costs of decisions that favour industry at the price of the ecosystem—commercial contracts are exempted from access-to-information laws. But the budworm infestation affected seven million hectares of Quebec’s forests this past summer, according to the forestry ministry, and while some researchers hope that it may peak soon, no one is certain what will happen next, in Quebec or elsewhere. During the last infestation, the budworm’s range of 58 million hectares extended across much of Quebec and the Maritimes, reaching east and into the US.

While regulations and ecosystems vary across those provinces and states, almost any business will prefer healthy trees to starving and dying ones. “This could happen anywhere. Any community, any institution could be making the same mistakes,” Kneeshaw said.

He is hoping that as the budworm spreads, people will talk openly about the trade-offs that must be made between economies and ecosystems. “The budworm takes about six years to kill a tree,” he said. “We have time to talk about how we want to handle this, and make good decisions.”

In a story about logging, there is almost always an argument about who bears responsibility. Is it the government, a forestry company, or someone else? But if we consider all those who tried to cope with the budworm infestation, or were affected by it—the forestry ministry, attempting to prepare for it; the academics who studied it; Villeneuve, trying to keep up the flow of wood to the paper plant; the hundreds of people who took part in the demonstrations in Baie-Comeau; Richard, dubious about the companies’ motives; the Baie-Comeau ministry workers and the officials who negotiated the agreement—the results that Kneeshaw found appear inevitable and the problem systemic.

“The Côte-Nord shows us that these outbreaks really shake the system,” said Bélanger of Nature Québec. “Theoretically, we’re prepared for the next earthquake. With these vast insect outbreaks, you’re never prepared. We have the illusion that what we’re doing is sustainable, that we will be able to continue what we’re doing indefinitely.”

Many of the more than 100 people we interviewed offered ideas about solutions for future situations like Baie-Comeau’s, in which the regional government is under pressure. “Transparency is an underlying issue,” Bélanger explained. “In a democracy, you need to have clear numbers, a clear economic evaluation. If we’d been private investors, we would have asked for this. The government should give us those numbers.”

Our requests to see the agreement between the government and the companies were denied. The black spruce and fir estimates that we have shared are rough because the MFFP merges fir and spruce numbers, partly to keep the companies from selecting which species they want—a policy that may no longer serve the public interest. The map that accompanies this article is limited to that strip of land because the 2000s survey of the forest that the MFFP completes every ten years is incomplete and overdue. And the public database of violations is not searchable.

“The problem is, yes, maybe we should give more information to people. But we should also have governments that are accountable, responsible for what they do,” commented Henri Jacob, a president of Action Boréale.

Similarly, researchers in the federal ministry said that in order to warn communities to prepare, they need better tools to be able to track the progress of the budworm and other insects. The Forest Insect and Disease Survey, a national monitoring system, was shut down some twenty years ago, a loss that still reverberates with some researchers.

Christian Hébert, an entomologist with the Canadian Forest Service who worked with FIDS, said that with each province now responsible for keeping track of the problems within its forests, if researchers want to examine another province’s data, but the data they need hasn’t been sampled, they must often pay to collect it themselves. “If you don’t use the same methods, if you don’t use the same tools, you have data that are hardly comparable,” he added. This makes it difficult for researchers to compile national maps of infestations.

Franklin Gertler, a lawyer who has worked with Indigenous communities on crafting agreements with the government, pointed out that Natural Resources Canada cannot step in if things start going wrong—it is not the equivalent of the Environmental Protection Agency in the US. “These are Crown lands,” Gertler said, “so the government’s acting both as regulator and as owner.” With the forestry companies primarily responsible for monitoring themselves, and the fir problem not within their area of responsibility, it’s unlikely that a problem such as the one Kneeshaw identified would be caught.

To help the community remain aware of changes in the forest, an idea was offered at the Territoire et Ressources office in Pessamit, a small Innu community whose ancestral hunting grounds, or Nitassinan, encompass the area where Kneeshaw surveyed the cutblocks. In a conversation about how best to monitor the fir problem and activity in the forest, three forestry workers there suggested that the Innu formally be granted this role. The community’s hunters and trappers do their traditional work in those forests and are likely to spot changes before anyone else.

In recent decades, ecologists have begun to argue for the need to maintain species such as the black spruce, since these are the ones we prefer to log. This idea can be compared to the activities of some Indigenous groups before the first Europeans began to discourage them—setting small burns to promote new growth and creating habitat for animals they hunted. Louise Gratton, a Québécoise ecologist, said that as logging activities have disrupted the natural processes that drive the ecosystem, we need to learn to actively maintain it.

“We need a forest for hundreds and hundreds of years to come, and with all the climate change and the other things that are going on, it’s going to be a real challenge,” she explained. She observed that in Quebec, undergraduates who are concerned about the environment have stayed away from the industry, when instead, they should be joining it. “I think that would be very attractive to students to become foresters, because they will be basically ‘the gardeners of the forest’ and that service that the forest provides us.” Because we have interrupted the relationship between spruce and fir, budworm and fire, through logging, climate warming, and fire suppression, we need to take up these tasks.

The greatest problem we face is that of time. How quickly it passes for us, and how slowly for the trees. Two hundred years ago, Ontario, western Quebec, and areas of the Maritimes were dominated by white pines: massive, ancient trees, up to seven feet in diameter, that loomed over the rest. Their trunks were used for the masts of British ships that fought in the Napoleonic wars, for the beams of warehouses in New York City—and then they were logged out. On the other side of the country, BC’s lodgepole pine was often considered a weed, ignored in favour of Douglas fir and hemlock until the growth of the pulp-and-paper industry; now it is sometimes planted in their place. Lately, forestry companies have been cutting trembling aspen, a leafy species that was once considered trash, and turning it into chopsticks. Across the decades, as one species is gone or played out, we start logging another and forget what stood in its place.

Richard, who says his family has worked at the paper plant for generations, alluded to this problem of changing baselines. “Decades ago, we used to log five or ten kilometres from the mill. With the infestation at our doors lately, when it was in the portion of the cut closest to the mill, the employer needed to go get wood 200 to 300 kilometres from the mill. That’s what increased their costs, and the government obliged them to log wood that was infested and not profitable, so the cost of production exploded. That’s why we had a crisis last year.”

In the Côte-Nord, the forestry industry is starting to adapt to new conditions—which may begin the process of pushing the memory of the nearby black spruce further into the past. In Port-Cartier, a logging town about two hours’ drive northeast from Baie-Comeau, construction on a new facility began this past summer, with the Quebec government’s support. The facility is expected to convert tree branches and other remainders—including damaged fir—from logging into fuel.

As warming brings more infestations, we are going to have to find common ground before we can prepare. If an infestation burns through, some communities may need to discuss not only the trees at risk, but also the ones that used to be there, and the ecosystems that will be needed in the future. To do that, many of us would have to make a difficult first step: a cultural shift.

We would have to accept that the forests that we know are changing in their varied ways and have been transforming for decades and even centuries. That with climate change and logging, our wilderness is no longer pristine, no longer self-maintaining. That some of our forests will be as dependent on us for maintenance as we are on them for timber. That we are now part of this ecosystem, whether we like it or not.

Investigators: Joseph Arciresi, Casandra De Masi, Michelle Pucci, Gregory Todaro, Michael Wrobel; with reporting by: Julian McKenzie, Shaun Michaud.

The investigative team would like to thank Concordia University and its Department of Journalism for its support in making this project possible.