It ended up being a quick decision. In the morning of October 7, Rob Pizzola’s boss at the digital sports media company, the Score, sent a company-wide email telling employees to stop betting on daily fantasy sports. That evening, Pizzola drove from his office in downtown Toronto to his home in suburban Kleinburg, forty-five minutes north of the city. His dogs—a great dane and a pug–dachshund cross—greeted him at the door. So did his wife, Diana. After dinner, he and his wife arrived at a decision: Rob would leave his full-time job as an operations manager at the Score, where he had worked for seven years. Instead, he would try to earn an income playing daily fantasy sports.

DFS is the logical evolution of sports betting, an industry split into two major categories: projecting the outcome of games, and fantasy sports. Operations like Ontario’s Proline—where you don’t bet on one team to win one game, but package multiple games together—have seen their market share cut by online offshore sports books offering micro-betting on individual contests. Meanwhile, fantasy sports pools continue to ride a consistent swell in popularity, where each week you pit your roster of players, drafted at the beginning of the season, against a friend’s team. But DFS is the ebullient lovechild of both micro betting and season-long fantasy. Instead of picking a roster for a season, DFS players select new rosters every day.

The web has wildly transformed the business of Canadian sports betting, a $15-billion industry of which only $500 million moves legally. Online operations from offshore sports books and stats-driven fantasy games have made betting increasingly complex. But both federal and provincial governments in Canada have stayed largely ambivalent in fantasy sports: nobody’s interested in shutting down your company’s March Madness bracket. In DFS, though, more money changes hands more rapidly. It’s a multi-billion dollar industry, and success breeds contempt. This November, the Canadian Gaming Association sought legal opinion on a claim daily fantasy is incompatible with the Canadian Criminal Code. They want it shut down.

These days, Pizzola wakes up around 10:00 a.m., later than he used to. His home office is filled with memorabilia of his favourite football team from childhood, the Dallas Cowboys. But fandom isn’t simple anymore. “If I need to, I’ll cheer against the Cowboys,” he says. Pizzola follows low-risk bets down easily trodden paths by preferring frequent small wins over single large payouts. His weekly earnings goal is $1,500, similar to his salary at the Score.

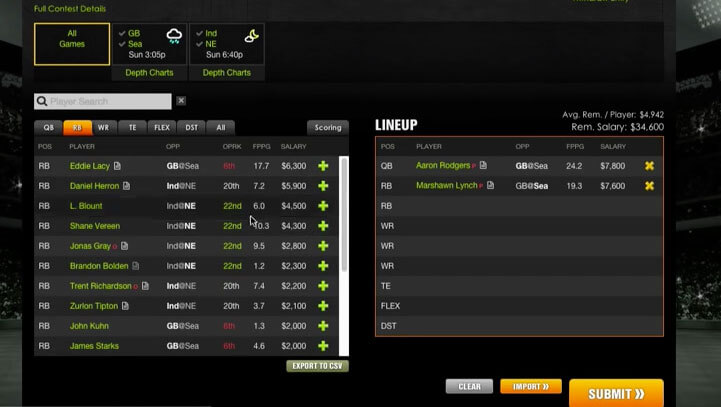

The majority of DFS players are minnows, betting a buck or two with one of the two billion-dollar companies that control the market: DraftKings and FanDuel. When Pizzola picks a lineup, he scrapes statistics and projections from the web and inputs them to his own spreadsheet model, which weighs the value of different data sets based on his parameters. “There are people who go to DraftKings and go through the players and pick ones they like and make a lineup,” he says. “That’s not me. I let the algorithm do the work.”

The Canadian Gaming Association is less laissez-faire. With more gambling revenue moving online, they hired the former general counsel for the Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario, Don Bourgeois, to examine the legality of DFS. They say it constitutes illegal gambling, and have circulated his report to provincial attorneys general. Public debate has centred on one phrase: “Game of skill.” Are DFS players illegally betting on the outcomes of sports games? Or are they engaged in a stats-based game where intense preparation—not luck—reigns supreme.

“Frankly, it’s a game of skill,” Rob says. “But it’s no different than gambling.”

In the late 1990s, when the Internet spurred the democratization of poker, huge swaths of people who didn’t previously bet on a card game were betting small amounts online. While in high school in everyone-knows-everyone Woodbridge, Ontario, Pizzola began betting on sports with “a guy you meet up with on Fridays, and either he pays you, or you pay him,” he says. More often than not, Pizzola did the paying. At one point, he owed almost five thousand dollars.

In his first year at the University of Toronto he continued to gamble on sports, and continued to lose, until he found poker. Making decent money online, Pizzola left school to play full time. “I made enough to make a living, but it was the worst,” he says. “I tried to treat it like a real job, wake up at nine, play until five, while Diana was in school. After a couple months, I was waking up at noon, playing for an hour, and doing nothing. There was no social aspect to it, I was totally alone.”

Pizzola returned to school and to sports, but this time he bet smarter. “When you lose,” he says, “you have to change your tendencies. So I started to think numerically.” He built statistical models, tracking what worked in search of that elusive edge. His arc mirrored the meteoric rise of DFS. Even though FanDuel has been operating since 2011, its revenue jumped from $14 million (USD) in 2013 to more than $50 million in 2014. In 2015, that number is projected to be close to $200 million. DFS entrenched itself in professional sports leagues, with multi-million dollar sponsorship and funding deals. It seemed too big to challenge.

On November 13, employees of DraftKings and FanDuel along with DFS players from across the US marched in downtown New York chanting, “Let us play.” “If Only Politics Were Skill Based,” read one sign, punctuated by the social media battle cry, #FantasyForAll. The state’s Attorney General Eric Schneiderman had just declared DFS to be illegal gambling. But the protestors pointed to their interpretation of a 2006 federal gambling law. You don’t gamble on DFS, they say, you play it. The state disagrees. On Friday, Justice Manuel Mendez ordered that daily fantasy is banned in New York, effective immediately. The “game of skill” rhetoric is also used in Canada, with one problem. In this country, it might not make a difference.

Canadian provinces run gaming operations under the jurisdiction of the federal Criminal Code: the provinces do the heavy lifting, but the federal government sets the rules.

While Section VII of the code defines a “game” as being of “chance or mixed chance and skill,” the definition of “bet” doesn’t make that distinction between games of skill or games of chance. There’s only one kind of legal sports betting in Canada, the kind the government operates. To date, no official legal challenge has ever been lobbed against DFS in Canada. The same goes for season-long fantasy sports, your office pool, and online offshore betting.

Online evolution continues to outpace the law, with governments struggling to keep pace. It’s not because web regulation is unprecedented: British Columbia’s online poker operation rakes in tax revenues.

Instead, Canada is still reacting sluggishly to the last dotcom-fuelled, sports-gambling boom: single game betting. A private member’s bill to legalize the practice passed through the House of Commons before dying in the Senate with the last federal election. Of primary concern to the senators was the integrity of professional sports, with organized crime historically extending its reach to baseball diamonds and basketball courts. Bill C-290 was introduced in 2011, before DraftKings even existed. If this is any precedent, DFS is in for a long slog.

On any given day, Pizzola makes two types of bet: short-term ones that his spreadsheets hedges, which he typically wins, and also a long-term bet on the future of DFS. While he’s confident he can get a new job if need be, Pizzola is pushing a big stack into a game where the rules have yet to be written.