When Nathan was in high school, his obsessive compulsive disorder derailed his education. He suffered from a version called pure obsessional, or pure O. Along with typical OCD rituals, like handwashing or hoarding, people with pure O are also plagued with unwanted mental imagery, much of it violent or grotesque.

Nathan (a pseudonym) never thought to ask his teachers in small-town Ontario for support, and he’s not sure he would’ve gotten any if he had. He failed grade-eleven math and grade-twelve English. He ended up moving to Toronto, where he waited tables, served at city hall, and worked for a queer publisher. Eventually, he finished high school and got grades high enough to be accepted, as a mature student, into the University of Toronto. This time, he was determined to thrive.

Nathan found that instructors expected a degree of mental toughness. He remembers a philosophy class in which a student attempted to apply a certain thinker’s moral ideas to a recent news story about a serial killer. When the discussion veered into the lurid details of the case, Nathan’s OCD spiked. He felt the familiar symptoms—panic, light headedness, shortness of breath, despair.

A few days later, Nathan approached his instructor privately. “In the future,” he recalls asking, “can you keep the conversation on track?” Her response was firm. She explained that class discussions are sometimes unruly, and while she’d continue to moderate them as best she could, it wasn’t her job to anticipate each student’s sensitivities. Nathan didn’t argue with her. “I told myself: That’s just the way university works,” he says. “I’ve got to either sink or swim.”

In time, he found the strength to handle different stresses—OCD, academic pressures—simultaneously. When he started getting the A grades that had eluded him in high school, he felt deeply proud. He had learned to manage his disorder while presenting to the outside world as a budding scholar. “U of T gave me a kind of resilience I didn’t know I had,” he says. “I’m grateful for that.”

He went on to get a PhD in English and then a position as an instructor at a major Ontario university. It was now his job, he believed, to uphold the standards that had served him so well in his undergraduate years.

In the early 2000s, he was teaching a literature course when he was contacted by a campus office he’d never heard from before: accessibility services. The office explained that one of his students, due to health concerns, would be unable to write the mid-term exam when scheduled. The request was short on details (what health concerns?) but direct in its demands. Holding a second exam, however, would eat up Nathan’s time. So he responded briskly: The date is set.

Accessibility services quickly got back to him with information that had been missing from the original message. The student had a diagnosed disability that impeded their focus late in the day. The explanation made sense, so Nathan had the student write a modified version of the test the morning after the official date. Then he forgot about the whole episode.

Eight months later, Nathan was forwarded a letter from the Ontario Human Rights Commission, addressed to the university president. The accessibility office, it turned out, had told the student about Nathan’s initial hesitancy to accommodate their needs. But pushback was only part of the problem. According to the complaint, Nathan didn’t act on repeated requests for volunteer note takers to assist the student during class. The complaint also alleged that Nathan continued to question the need for morning testing and went so far as to suggest the student drop the evening course altogether.

By resisting the student’s request, the letter alleged, Nathan had violated their “rights under the Human Rights code.” He’d also erred by giving the student a different exam from the one their peers got. The complaint indicated that the student, distressed, had filed a petition for a late withdrawal from the course. Nathan would have to defend himself in front of the province’s human rights tribunal. He wondered what would happen if the hearing went poorly. Could he lose his job?

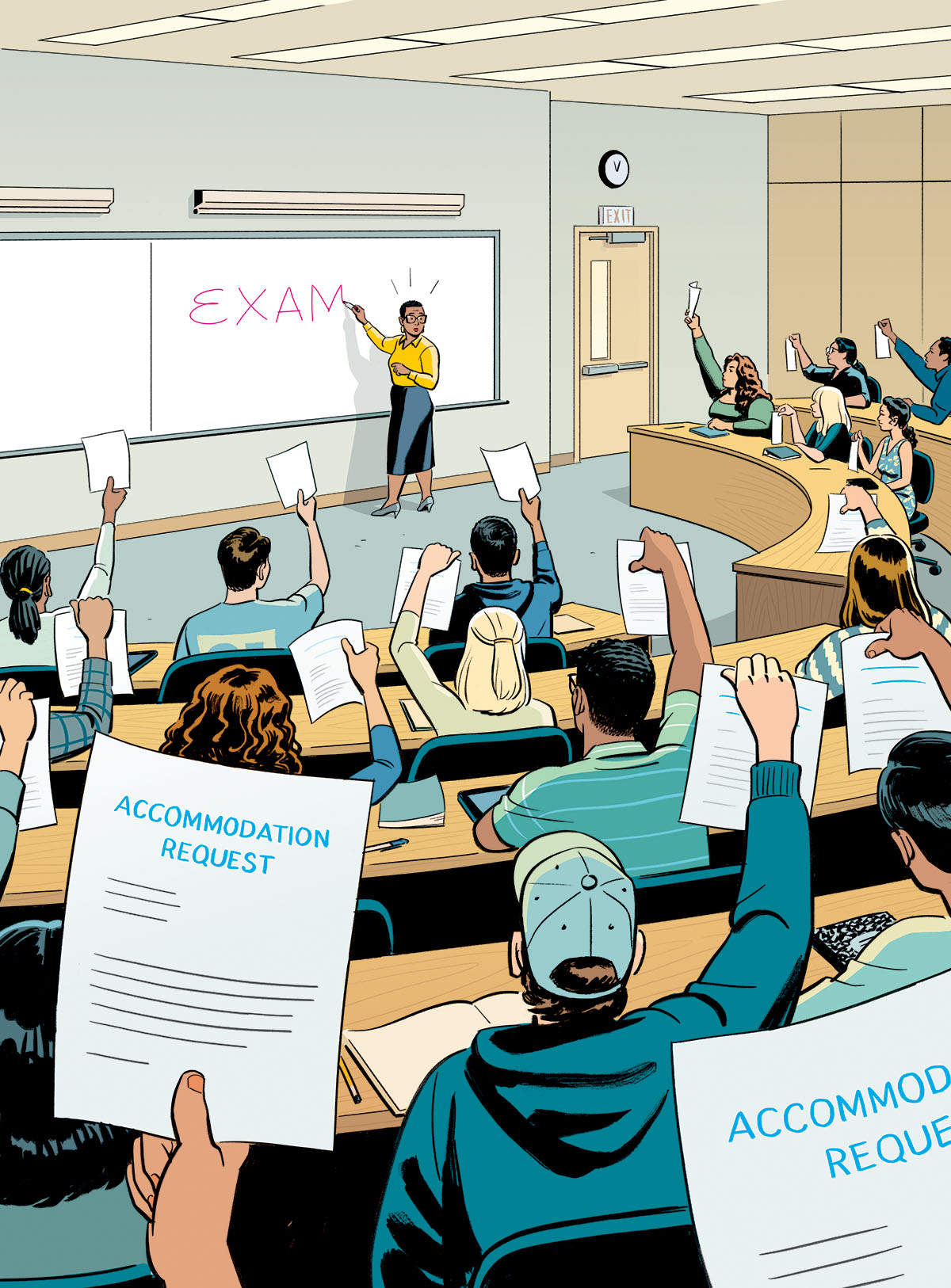

Since 2017, I’ve been teaching courses on writing at the University of Toronto. In these seven years, not a single week has gone by in which I haven’t gotten a request for an accommodation of one kind or another (an “accommodation,” in this context, is an adjustment to course delivery, expectations, or grading criteria). Some requests come from the university bureaucracy; others come from the students themselves. Some are backed by medical documentation; the overwhelming majority are not.

I’ve been asked, variously, to excuse multiple absences, to redesign assignments at the last minute, to offer additional make-up assignments, to give passing grades to non-existent work, to stream in-person classes on Zoom, to offer one-on-one tutorials outside of class hours, to provide written notes in lieu of missed lectures, to accept email submissions in lieu of class participation, to grade rough drafts in lieu of finished products, to extend deadlines, to extend deadlines again, and then to extend them one more time. I don’t have exams or tests in my courses, but if I did, I’d surely be asked to reschedule them or to allow students to complete them at home. Other instructors get demands like these all the time.

I grant some requests; I resist others. Frequently, I’m unsure what to do. The sheer quantity of emails I get is dizzying, and I’m often overwhelmed. Sessional lecturers (that is, people like me who teach on contract) are notoriously underpaid. I get $10,000 for a semester-long course, an amount that puts me near the top of the income range. My peers at other institutions get as little as $4,000. Teaching, for me, is a bit like collecting vinyl LPs: it’s financially irresponsible but I do it because it gives me a kind of joy I can’t get any other way. I supplement my teaching income by taking on more lucrative gigs as a magazine journalist.

Because I’m overworked, I receive most student emails in a state of exhaustion. But the students emailing me are exhausted too. Many are working part-time jobs at irregular hours to cover their tuition and inflated downtown rent. Many are living independently for the first time, managing extreme loneliness in a big, atomizing city. Many are contending with anxiety and depression (rates among youth have skyrocketed in the past decade) or even with the first signs of mood disorders, which often present in a person’s late teens or early twenties. Are some students also lazy, entitled, and poor at managing time? Sure. But those students are good at coming up with plausible excuses. There’s no way for me to know who’s telling the truth and who isn’t.

And so I respond to accommodation requests by muddling through on instinct, seeking solutions that seem fair to me and don’t inundate me with extra work. Each decision feels like a small patch to a broken system. I worry that university bureaucracies are robbing instructors of their academic freedom by compelling them to offer accommodations that don’t match their teaching styles or the content they teach. I worry that accommodations aren’t reaching the people who need them most. A student in crisis isn’t always the best self-advocate. But others—those who are unafraid to make bold demands of their instructors—may be getting help they don’t actually need.

Most of all, I worry about the risks of being too lenient—or not lenient enough. If I deny all accommodation requests (except those that are imposed on me by bureaucratic fiat), I’ll make my class inhospitable to students with disabilities or other serious life challenges. That’s unconscionable. But if I grant too many requests, I’ll create a class without stress or friction—the stuff that makes learning happen.

In the fall of 2022, New York University made international news when it fired a chemistry instructor named Maitland Jones, Jr. A retired Princeton professor who taught on contract at NYU, Jones was known as an exacting educator. In the spring of 2022, his course on organic chemistry was the subject of a petition, with more than eighty students complaining of poor test scores and Jones’s “condescending and demanding” teaching style. Jones acknowledged that an unprecedented number of people had performed poorly in his class that year. He believed that the grades partly reflected a pandemic-era decline in the work students were doing. NYU fired him anyway.

The story went viral. It captured what many people saw as an industry-wide phenomenon—a shift in standards, perhaps, but also a shift in power. The Academic Freedom Alliance, an American nonprofit that defends free speech on campus, declared that NYU’s decision “appears to be another example of the trend in higher education to devolve more academic authority from faculty into the hands of administrative entities.” In an op-ed for the Boston Globe, Jones struck a similar note: “The growing number of administrators, major and minor, who are often without any expertise in a given subject matter, need to learn to stand back from purely academic matters and to support the faculty.”

Greg Lukianoff—president and CEO of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, a US group that supports civil liberties—believes that administrative bloat is eroding academic norms. Until the ’70s and ’80s, Lukianoff explains, schools were mainly self-governing. Professors taught courses, but they also ran the institutions and set the rules for student conduct. If their classes were sometimes unforgiving, it’s often because they sought to uphold standards of excellence. (Or so they said. Some were also dyspeptic hardasses or bitter old curmudgeons.)

Today, high-ranking professors may still occupy the top administrative positions. Beneath them, however, is a phalanx of bureaucrats who do most of the real work. They mediate disputes between students. They investigate and punish academic misconduct. They make statements on the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion. And they encourage (or sometimes compel) professors to make such statements themselves.

They also host workshops on how best to run a classroom. The content of these seminars is often presented as friendly advice, but instructors who don’t heed that advice can occasionally find themselves reprimanded or penalized. In some cases, their contracts aren’t renewed. “Bureaucratization,” says Lukianoff, “is a symptom of institutional decline.” His point is not that universities are dying (they certainly aren’t) but rather that they are becoming less focused on core values, like intellectual freedom, rigour, and the pursuit of truth.

Is bureaucratization all bad, though? Defenders point out that administrators exist for a reason. Academics are experts in their fields of study; they’re not necessarily experts in teaching. They don’t always understand the stressors that students today face. And they aren’t typically reading the most up-to-date research on classroom inclusivity. Doesn’t that give the staff at accessibility offices some licence to tell instructors what to do? Who else is going to set baseline standards for consistency and fairness?

Moreover, accessibility officers aren’t just inventing rules on the fly. They often work within an established school of thought. In 1966, a man named Ronald L. Mace—a polio survivor who’d used a wheelchair since age nine—graduated with an architecture degree from North Carolina State University. He’d gotten around the school by having classmates carry him up and down the stairs. After convocation, he advocated for what he called universal design, a set of norms—which include ramps, elevators, Braille signage, wide hallways—to help people move seamlessly through their built environments.

In the 1980s, David Rose and Anne Meyer, researchers in education at Harvard University, began adapting Mace’s architectural principles to their own field of study. An accessible classroom, they argued, isn’t just one that students can physically get to; it’s one that complements an array of learning modes and aptitudes. Rose and Meyer’s movement, Universal Design for Learning, is now a big deal, at least in the niche field of education studies.

But the debates over UDL are still in play. While there’s an agreed upon framework, there’s no consensus as to what universal design entails in practice. Some UDL proponents favour flexible deadlines. Some discourage instructors from requiring participation in class. Some are critical of timed assessments, like tests and exams. Some suggest that instructors should Zoom their lectures in real time—or record their lectures and post them online afterward—for the benefit of students who can’t come to class. Some focus on ways to overhaul PowerPoint presentations. If your slides have images, they argue, those images should come with descriptions that can be captured by screen-reading technologies used by students with visual impairments or students who are blind.

Many UDL proponents want instructors to think more expansively about how they define success. Is the formulaic undergraduate essay—3,000 to 5,000 words of turgid prose—the best fit for every type of pupil? If a tech-savvy student who’s better at talking than writing wants to record a podcast instead, why not let them do it? “Assessments should be meaningful,” says Seán Bracken, a lecturer at the University of Worcester, in the United Kingdom, and a leading UDL researcher, “not just to students but also to wider society.”

Bracken says that, in the past, universities have defined intelligence much too narrowly. A student with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, may struggle to focus in class; a student with social phobia may struggle to speak in class; and a student with sensory processing sensitivity may struggle even to get to class, but all of them could be top-notch thinkers. Schools, he believes, should welcome their contributions.

Sam Catherine Johnston, who heads the post-secondary division at the Center for Applied Special Technology, the organization that pioneered UDL, argues that such principles can improve everybody’s learning experiences, instructors included. “All of us can benefit from the good things that happen when learning design is optimized for a broad range of people,” she says. “Suddenly, students can learn with—and from—one another much more effectively than they did before.” An inclusive classroom, by this reasoning, is a vibrant classroom too. Who wouldn’t want that?

The answer is complicated. Ask a university instructor, on the record, what they think of UDL, and they’ll likely say they’re on board. Ask them in private, and they may confess to misgivings. Over the years I’ve spent reporting on higher education, I’ve realized that academics are often afraid of public statements that could put them on the wrong side of progressive orthodoxy. Precariously employed contract instructors fear losing their jobs; tenured professors fear the disapproval of peers.

To be clear, few instructors oppose UDL wholesale, and almost everybody wants their classrooms to be inclusive. But many educators worry that UDL principles are being deployed thoughtlessly, in ways that make their jobs difficult. And while they admire UDL as a philosophy, they fear that, in practice, it’s becoming dogma.

During the pandemic, an instructor I’ll call Maya, who teaches psychology at a university in western Canada, was forced, like everybody else, to rethink her assessments. Instead of in-class exams, she and seemingly all of her colleagues issued online tests with flexible start and finish times, the better to accommodate students Zooming in from different parts of the world. She assumed this change was temporary: surely, in due course, the COVID-19 emergency would die down and everybody would go back to the usual way of doing things.

When the pandemic ended, though, she encountered resistance from some students. “They would say to me, ‘Why do I have to write tests by hand and not with a computer? Why can’t I have the option to do tests from home?’” she recalls. She also noticed other instructors continued with the more flexible testing format. In a world where all information is available online, the argument went, why did it matter whether people could recall facts from memory? And was testing even fair? Didn’t it favour some students—those who think quickly, despite mental stress—over others?

Students have been writing tests since at least the sixth century, and Maya never suspected that she’d be called upon to defend this tradition. The benefits of testing seemed obvious. Many people in her classes aspire to become doctors. To achieve that goal, they’ll have to pass the Medical College Admission Test, a notoriously tough exam, and to thrive in the profession, they’ll need to perform quick diagnostic assessments in situations of immense pressure. Cool headedness, grace under fire, a solid command of basic facts—to Maya, these skills are hardly superfluous. “It’s part of my job to prepare students for the professional world,” she says.

Students, of course, have their own ideas. At the beginning of the fall 2023 semester, an instructor I’ll call Lisa, who teaches political science at a university in Atlantic Canada, caught a student surreptitiously recording one of her lectures—an act that, for her, amounts to intellectual property theft. She called out the student in class; the student approached her afterward, and the exchange got heated. “I hope you know I have an accommodation,” she recalls the student saying angrily. Lisa had more than 100 students in the class, and, by her estimate, at least twenty had accommodation letters. There was no way, so early in the term, for her to figure out who was who. Lisa explained that, while she was happy to meet the student’s needs—for instance, by offering password-protected access to online lecture recordings—she wouldn’t allow anybody to bootleg her classes. The student was apoplectic. “They didn’t show up for an entire month,” Lisa recalls.

She became curious about the source of the student’s sense of entitlement. What is it that people are being told at accessibility services, she wondered. When she began reading carefully through the accommodations policies at her university, she realized that the student’s expectations hadn’t been misguided. “The website says, basically, that students, along with the accessibility office, will come up with their own accommodation plans,” says Lisa, “and that faculty must accept those plans.” She has since noticed that accommodation letters never allow space for an instructor’s input. “The only thing I’m allowed to write is my signature,” she adds.

Many educators feel as if they’re being cut out of the accessibility conversation altogether. In the winter of 2024, an instructor I’ll call Elise, who works in the English department at a major Toronto university, was hired to teach a first-year class on essay writing and composition. A month into the class, Elise says, the course coordinator—who manages the various sections—called her and her colleagues into a meeting to discuss grading policy. Students, she said, wouldn’t be tested at all, and while they’d be encouraged to participate in class, they wouldn’t be required to do so. Instructors would evaluate pupils, instead, on their written work, focusing largely on content rather than style or grammar.

Class discussions were a slog. Lacking an incentive to read or speak, students did neither. When Elise asked even simple questions about the readings (“Did you enjoy them?”), she was met with stony silence. Every time an essay deadline approached, Elise says she was inundated with email requests for extensions. She granted all of them. “I don’t think I ever received more than 50 percent of the papers on time,” she says. She also marked essays generously, giving B+ grades to work that, in her opinion, was worthy of a C.

Leniency had become a survival strategy. As a contract instructor, she works punishingly hard for between $40,000 and $60,000 a year, and she knows that haggling with students over deadlines or grades can add four to ten unpaid hours to an already exhausting week. But it isn’t just extra labour that worries her. If a student responds to a poor grade or a firm deadline by alleging discrimination on the basis of disability, will the course coordinator back her up? The pre-semester meetings didn’t exactly fill her with confidence. “When you’re a contract lecturer, you know you’re disposable,” Elise says. “That’s why I’m afraid of my students. I don’t want them complaining about me or drawing attention to me in any way.”

The experience has left her profoundly disillusioned. A classroom, she says, is supposed to be a dynamic place, where people think out loud together. A university, moreover, is supposed to enlarge student capacity for attentive work and original thought. Elise doesn’t think her students are doing very much of that. “What skills are we trying to cultivate in this course?” she wonders. “Not verbal communication or time management or professionalism. We’re not even trying to teach basic writing conventions. If none of these things matter anymore, it’s unclear to me what does.”

Lucy—not her real name—works in accessibility services at a university in the Greater Toronto Area. She says the system’s biggest problem is a lack of resources. She estimates that, in the past five years, the number of students seeking accommodations has doubled or perhaps tripled, but the staff hasn’t grown at anything like that rate. “The caseload average is about 300 to 400 students per adviser,” she says.

The results are predictably grim. Students can be forced to wait two or three weeks for a brief meeting. Advisers must sometimes work fifteen-hour days to keep pace with demand: burnout is endemic, and annual turnover is high. Instead of working with students to devise innovative, bespoke solutions, Lucy says, staff often revert to quick fixes—mostly, deadline extensions and exam deferrals.

Those fixes, she argues, are effective: a student in acute crisis may need just a brief respite from academic pressures to focus on their health. But other students can find themselves saddled with unmanageable levels of backlog. “The end of the semester is inevitably busy,” Lucy says. “If they add on another paper or two that they didn’t finish at mid-term, they’re creating a perfect storm.”

While students today may have an easier time negotiating deadlines—or getting excused from class discussions or timed assessments—those with diagnosed disabilities must still fight to get the accommodations they need. A master’s student at the University of Toronto, whom I’ll call Lily, has a disability that makes long commutes impossible—a big challenge, given that her degree program requires her to accept fieldwork placements off campus. The support Lily gets from the accessibility office is frequently patchy. The staff, she says, are clearly overextended, and her advisers keep quitting and getting replaced. When a new adviser comes in, Lily risks having to resubmit her medical paperwork.

This May, Lily put in applications for the final professional placement of her degree. She had specific requirements—that her placement be hybrid or virtual and that the commute be no longer than thirty minutes. But the letter of support the accessibility office sent her had major errors. Lily emailed her adviser to request corrections and was told to make a formal appointment. She then called the office, but they were unable to book her until after the application deadline. She emailed her adviser several times more but to no avail. (“She’s kind but extremely busy,” she says.) Eventually, she found her adviser’s phone number online. After several panicked calls, she managed to get through—and get the proper documentation. It wasn’t the first time she’d almost lost accommodations over a tardy letter. “It’s frustrating to have to go through these experiences every time I need assistance,” Lily says. Accessibility services are supposed to help—not stymie—her.

Before Daniella Levy-Pinto began her PhD in political science at U of T, she set up a meeting with accessibility services. Levy-Pinto, who is blind, says the accommodations she received were so rudimentary, they barely qualified as accommodations at all. Her readings were scanned and sent along as electronic files. She could then export the documents from PDFs to text-based formats and run the text through other software applications to eventually be read out loud. But these applications make mistakes all the time. Virtually anything can trip them up—a diagram, a unique typographical marker, like an asterisk or accent, or a note scribbled in pencil on the document before it was scanned. “They were like crossword puzzles,” Levy-Pinto says of the resulting files. “I constantly had to guess at mystery words.”

Accessibility services, says Levy-Pinto, advised her to track down cleaner versions of the texts: perhaps she could ask her professors to scan their personal copies, or she could hunt online for versions that were optimized for screen-reading technology. But Levy-Pinto was already doing these things, and they were eating up her time. “Half of my workweek was consumed by self-advocacy or self-accommodation,” she says.

She soon realized that she was pulling the wrong bureaucratic strings. And so she demanded meetings first with the head of her department and then with the dean. By the end of her first year, she was given the accommodation she’d needed all along—a personal assistant who would go through the course texts, page by page, and remove irregularities that might foil a screen reader. Today, Levy-Pinto isn’t angry at accessibility services so much as disappointed. “They were helpful to the extent that their bureaucratic mandate allowed them to be,” she says. “For many problems, they had no ready-made solutions. I went to them only when I needed a signature on a letter.” (In a statement to The Walrus, a university media relations spokesperson wrote, “We are working hard to anticipate and meet students’ needs—and acknowledge that there is more work to be done.”)

When Ka Li, who is also blind, enrolled in kinesiology at York University, he knew he was taking a risk. Blind people, he says, often opt for reading and writing-based subjects, rather than STEM programs, which require practicums and lab work. To manage these hands-on endeavours, accessibility services suggested lab assistants. In theory, the assistants would take directions from Li; in practice, some tried to do the work for him. “It wasn’t the symbiotic relationship it should have been,” Li says. “Some had no sense of blind people’s capacity to do things for themselves.” (A York University spokesperson wrote in an email to The Walrus, “We are deeply committed to doing all we can to reducing and eliminating barriers.”)

And so he became his own accessibility adviser and coached university staff on how best to support him. During dissection—in which a professor labelled organs and muscles in front of the class—Li would explore the specimens with his hands, fingers, and nails. When the university bureaucracy said that accessible versions of his textbooks would be unavailable until halfway through the semester, Li showed his instructors how to produce tactile drawings of textbook diagrams. And when he learned the campus didn’t have a Braille embosser—a printer that produces documents in Braille—he bought one with $4,000 of his own money. He estimates that, during the course of his degree, he spent $16,000 on assistive technology. What else could he do? “I basically gave up on accessibility services,” Li says. (In a statement to The Walrus, a York University spokesperson wrote, “We work closely with students needing support to offer a broad range of accommodation and access services.”)

One may be tempted to cast the accommodations debate as generational, pitting young learners, who like the new way of doing things, against older professors, who don’t. But students are dissatisfied too. Elise sometimes hears from pupils who wish instructors would set firmer boundaries. When deadlines are endlessly extendable, they tell her, you tend to procrastinate, particularly if you suffer from OCD or perfectionism. “Some people will put all of their assignments off until the end of the semester,” Elise says, “at which point they can’t possibly get everything done.”

Pedagogical theorists often talk about the “learning zone” model of education, which can be visualized as a set of three concentric circles. The inner circle represents the comfort zone, in which learners are at ease and complacent, and the outer circle represents the panic zone, in which learners are overwhelmed. Learning happens in the middle circle—the sweet spot. It is an adaptation to stress, but not the debilitating kind. Educators, by this reasoning, should create just enough friction to foster intellectual growth but not enough to break people.

Too often, our universities are failing to find that balance. When we force students with disabilities to navigate a dizzying campus bureaucracy, or to adapt wholesale to hostile learning environments, we make their lives impossible. In so doing, we exclude them from the benefits of higher education—benefits we gladly extend to their able-bodied peers. A rigid university system is, almost by definition, a discriminatory one.

But we don’t do students any favours by creating a generalized culture of leniency. Managing deadlines, speaking publicly, showing up on time, thinking under pressure—everybody struggles with these challenges. Overcoming them is a form of growth, the kind universities exist to nurture.

Occasionally, colleagues have criticized me for the somewhat old-fashioned way I run my classroom. I’m not stodgy about everything. I grant bespoke accommodations to students with disabilities of any kind, so long as the request seems remotely reasonable, and I don’t require documentation (I’m about as enthusiastic about bureaucratic protocols as my students are). For better or for worse (probably worse), I can’t be bothered to enforce deadlines either.

But I hold the line on a few things. Classes happen in person only. Lectures are not recorded or beamed out over Zoom. Screens of any kind are forbidden in my classroom. I correct written grammar and style. Class participation is mandatory. I insist on these rules because the skills required to comply with them—clear communication and the ability to exchange ideas in real time, unencumbered by digital distractions—are the skills I’m trying to foster. The overwhelming majority of my students rise to the challenge. In anonymous course evaluations, many report that they’re glad they did so. The experience may be daunting at first, but things worth doing usually are.

For this reason and others, proponents of UDL could stand to adjust their messaging. UDL is at its best when it focuses on effective accommodation practices that can be targeted to individual students. It’s on shakier ground when it insists on relaxing standards across the board. And if UDL proponents really want to bring about systemic change, they need to more fully embrace the cause of pay equity for contract instructors. If the plan is simply to hope that exhausted, precariously employed instructors will embrace the cause with zeal, then there isn’t really a plan at all. Instructors must be incentivized to do UDL’s heavy lifting. “Precarity of employment means you’re not going to be receptive to UDL,” says Frederic Fovet, an assistant professor in education at Thompson Rivers University, in Kamloops, BC. “When I was a contract instructor, I taught forty-nine master’s courses in three years. I’m a UDL specialist. But do you think I did UDL in my classes? No, I did not have the time.”

Campus bureaucrats could stand to shift their mission too. Accessibility offices shouldn’t mainly be places where students get letters telling their instructors to be lenient. They should be hubs where experts connect students with the best practices, the best technologies, and the best resources to meet their specialized needs. None of this will be cheap, but equity rarely is. Accessibility officers could also stand to be more tactful in their dealings with the professoriate. Instructors don’t like receiving edicts from on high, and they don’t like being threatened with reprisals for doing what they believe is their job. They are also necessary allies in the accessibility mission. They should be included in the conversation.

After Nathan received the letter informing him of his tribunal hearing, the university provided him with legal counsel. His lawyer advised him to swallow his pride and admit to wrongdoing in exchange for forbearance. At the hearing, Nathan apologized for the harm he’d caused. It hardly matters whether his words were sincere: the university paid a $1,000 fine on Nathan’s behalf, and he kept his job.

The experience has left him with mixed feelings. At times, he worries that a culture of toughness—one that nurtured his young intellect—is no longer available to students who may benefit from it. At other times, he wonders if toughness is perhaps overrated. “I have found myself reflecting on past instances in which I’ve been a hardass for no good reason,” he says. Mostly, though, he doesn’t think his opinions matter. Two decades of work as an instructor doesn’t buy him a whole lot of clout in the accessibility debate. “These days,” he says, “when I get a letter from accessibility services, I shut up and do what I’m told.”