Lake winnipeg is large and changes colour. As summer progresses, parts of it slowly shift from milky mahogany to bluish green, and by August, it can be emerald in places, as vivid as a golf course. From space, it looks as though someone poured a giant kale smoothie onto the Manitoba landscape.

What the satellites are picking up are billions of tiny aquatic organisms that, individually, are usually visible only under a microscope. They can be long and thin, like a sliver of grass, or short and round, like a squishy stress ball. They might fan out like miniature ferns, or form star patterns as intricate as a snowflake. Some have little tails to move through water; others simply float. All are considered species of algae, and they feed on nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus. When too many nutrients pour into a lake, these life forms grow in wild unhinged abundance.

Among the many kinds of algae that thrive in Lake Winnipeg are cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae. One of the most successful micro-organisms on the planet, they once performed a billion-year photosynthesis project that helped generate the oxygen in our atmosphere. When those ancient algae died, they formed the oil deposits we use to power cars and jets. Today, toxins in blue-green algae can kill a dog that’s splashing around in an afflicted lake—sometimes in under an hour.

In August 2015, biologist Eva Pip travelled to Hillside Beach in the south basin of Lake Winnipeg—about an hour-and-a-half drive from downtown Winnipeg—to look for neurotoxins in the algae. She’d been going out to various beaches every three days since spring, collecting samples and testing them for beta-methylamino-L-alanine, or BMAA—an amino acid that cyanobacteria can produce and that has been linked to degenerative brain diseases including Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and Parkinson’s.

The beach was full of people. Hillside is a sandy, shallow inlet. There are no boardwalks, no shacks selling ice cream—only families with small children, and locals carrying coolers. Grandparents lounge in beach chairs, and parents loll on colourful towels, watching their kids splash one another with turbid water.

Pip cut an eccentric figure as she sloshed out of the lake, wearing hip waders and carrying water samples—and even more so when she started addressing the young children, cautioning them not to play with the thick, viscous mats of dead algae that had washed up on shore.

She wears her hair in a loose bun, so that the tops of her ears peek out through the brown and slightly grey wisps that spray down to her shoulders, and her eyes are bright and blue. But her mild appearance is misleading. She has become Lake Winnipeg’s own weeping Jeremiah—or, in a modern version of that archetype, its saddest and angriest scientist.

Lake Winnipeg is the tenth-largest freshwater lake in the world. For decades, it has suffered from severe eutrophication, a process that results when aquatic ecosystems are overwhelmed with nutrients, usually from local runoff. But disagreements persist over how serious the problem is: it might spell doom for the lake’s food web and pose dangerous health risks to those who use it, as Pip argues, or it could just be a cosmetic blight that threatens tourists’ and cottagers’ enjoyment of the water. It’s either an ecological disaster or a late-summer nuisance—or something in between. Many who live by the lake are now accustomed to the green sludge and occasional stench, and they seem just as likely to dismiss the problem as join a campaign to fix it.

Pip remembers the first time she collected samples on Lake Winnipeg, back in 1961, when the water was so clear she could see the kaleidoscope of colours formed by pebbles on the lakebed. Since then, the lake has suffered a barrage of attacks: fertilizer that’s washed directly into the waterways from nearby fields; overflow from municipal sewage systems; the contents of faulty septic tanks. All of it ends up in Lake Winnipeg.

Toxic algal blooms have been wreaking havoc all over North America. Three years ago, an eruption of algae in Lake Erie left more than 500,000 water customers in Toledo, Ohio, without drinking water. Last summer, blue-green slime coated rivers and beaches in Florida, prompting a state of emergency in four counties. In July 2016, 130 people reported vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, and rashes after coming in contact with algae-infested Utah Lake.

On that August day two years ago, Pip claims to have found BMAA levels of 306 micrograms per litre—“a very high concentration,” she said. There are hardly any standards regulating BMAA in Canada, because it isn’t studied much here. But BMAA testing isn’t a settled matter in other countries, either. Gregory Boyer, a biochemist at the State University of New York, has, for example, called into question the very accuracy of such measurements. He points out that some methods make it easy to confuse BMAA with other amino acids of the same molecular weight. He also believes BMAA isn’t present in Lake Winnipeg, because his work didn’t show it. For her part, Pip argues that no one wants to admit how toxic Lake Winnipeg algae might be because the economic fallout of a crippled fishery and tourism industries would be severe. A poisoned lake is one thing, a poisonous lake quite another.

Pip’s biggest quarrel is with government scientists. “I’ve been extremely disappointed by how apathetic the community has been,” she told me. In 2016, she retired from the University of Winnipeg, where she’d studied more than 650 lakes and contributed to more than 123 published studies. “You’re supposed to behave the way everybody else does, and then you’re one of them,” she says. “But if you’re outspoken, then you’re an alarmist.”

Her outspokenness has made Pip perhaps the most controversial scientist in Manitoba. Mention her name among researchers who study algae or work to improve the water quality of Lake Winnipeg, and you’ll likely trigger strong responses ranging from irritation to concern. Some regard her crusading—especially her penchant for making dire pronouncements that win the attention of news outlets—as deeply off-putting.

Karen Scott is the educational program coordinator for the Lake Winnipeg Research Consortium, which helps researchers collect data on the lake from sixty-five monitoring locations. Over the last few years, she has taken on the role of myth buster. She meets with community groups to explain why messages such as “The lake is dying” and “The lake is toxic” aren’t accurate, no matter how often the media reinforces them.

First, the lake is technically too alive: there are too many nutrients feeding too much algae. Second, such statements create the false impression that the toxins are ubiquitous, when in fact they’re present only in some algae and then mostly in late summer if the algae are blooming. Calling the whole lake toxic, says Scott, is like saying a forest is poisonous because poisonous mushrooms grow in it.

Like Pip, Scott works to make people think more carefully about their relationship with water. But she operates at the other end of the sensationalism spectrum. When Scott talks to the public, she tries to convey a simple message: “Water moves.” We may see it for only the fraction of the second it takes to travel from the faucet to the drain, but it travelled far to soak our toothbrushes, and has farther yet to go. Lake Winnipeg, in other words, isn’t just the large body of algae-packed water in Manitoba: it’s part of an enormous watershed that spans about a million square kilometres between the Canadian Shield and the Rocky Mountains. Water moves, past farms and factories, through pipes and ditches, in and out of towns and cities. Sooner or later, it all ends up in the same place, along with everything it picked up along the way.

How much people value water often depends on whether it’s moving away from or toward them. For the farmers and city dwellers upstream, what’s out of sight passes easily out of mind. But for the Indigenous people and cottage communities near the lake, what the others ignore is bright green and hard to miss.

More than 400 kilometres long from bottom to top, Lake Winnipeg consists of two distinct sections: a smaller south basin, home to a handful of Indigenous communities and most of its public beaches and cottages, and a larger north basin that includes part of the pickerel and whitefish fishery.

Despite its enormous size, Lake Winnipeg is a small remnant of a much bigger lake that once covered the entire province of Manitoba and large sections of Ontario, as well as parts of Saskatchewan, Minnesota, and North Dakota. Lake Agassiz was formed at the end of the last ice age by meltwater from a glacier that was four kilometres thick and so heavy it depressed the Earth’s crust by 100 metres. As the glacier melted, the land started to spring back, causing some of the water in the region to travel north, toward Hudson Bay and the Arctic Ocean.

When Lake Agassiz drained out to sea, it left behind a flattened landscape full of lakes and bogs. Today, after a summer rainstorm, the fields look as if they’re trying to return to their former sogginess. Water collects in every indentation, filling the ditches and forming dirty brown ponds amid otherwise lush crops.

Farmers have been waging war on Manitoba’s waterlogged landscape for more than a century. Their aim is simple: get rid of the water. Over the last thirty years, we’ve lost more than 100,000 acres of wetland—the equivalent of four and half football fields a day—many of which were drained to create additional arable farmland. The government has carved out a vast network of drainage ditches across the Manitoba prairie to move rainfall and snowmelt off the fields—and drain the wetlands—as quickly as possible. At one time, the wetlands absorbed spring snowmelt like a sponge and released it slowly over the summer; now, though, that water races north to Lake Winnipeg all at once.

To make matters worse, there’s also more water to contend with. Although precipitation comes in multi-decade cycles of dry and wet, the latest wet period, which started in the mid ’90s, is much wetter because of climate change. Hotter temperatures cause more evaporation and greater rainfall. Water is steaming off the Gulf of Mexico, and low pressure systems are bringing it north to Manitoba. Consequently, the Red River Basin, a fertile region south of Lake Winnipeg that includes parts of North Dakota and Minnesota, has doubled its flow of water to the lake in the last twenty years.

The Manitoba landscape is naturally prone to flooding, but the combination of the ditches, wetland loss, and increased precipitation has exacerbated the problem dramatically. The province has had roughly fourteen floods since 1996, at least four of which washed out roads, displaced-people from their homes, and prompted states of emergency.

It’s no coincidence that the current wet period corresponds with the rise of persistent algal blooms. The water carries fertilizer from fields, and leaches phosphorus from dead plants left on the ground over the winter (farmers call them “plant litter”). Even though the Red River represents only 15 percent of the water that enters the lake, it’s responsible for 70 percent of the nutrients. And more nutrients mean more algae.

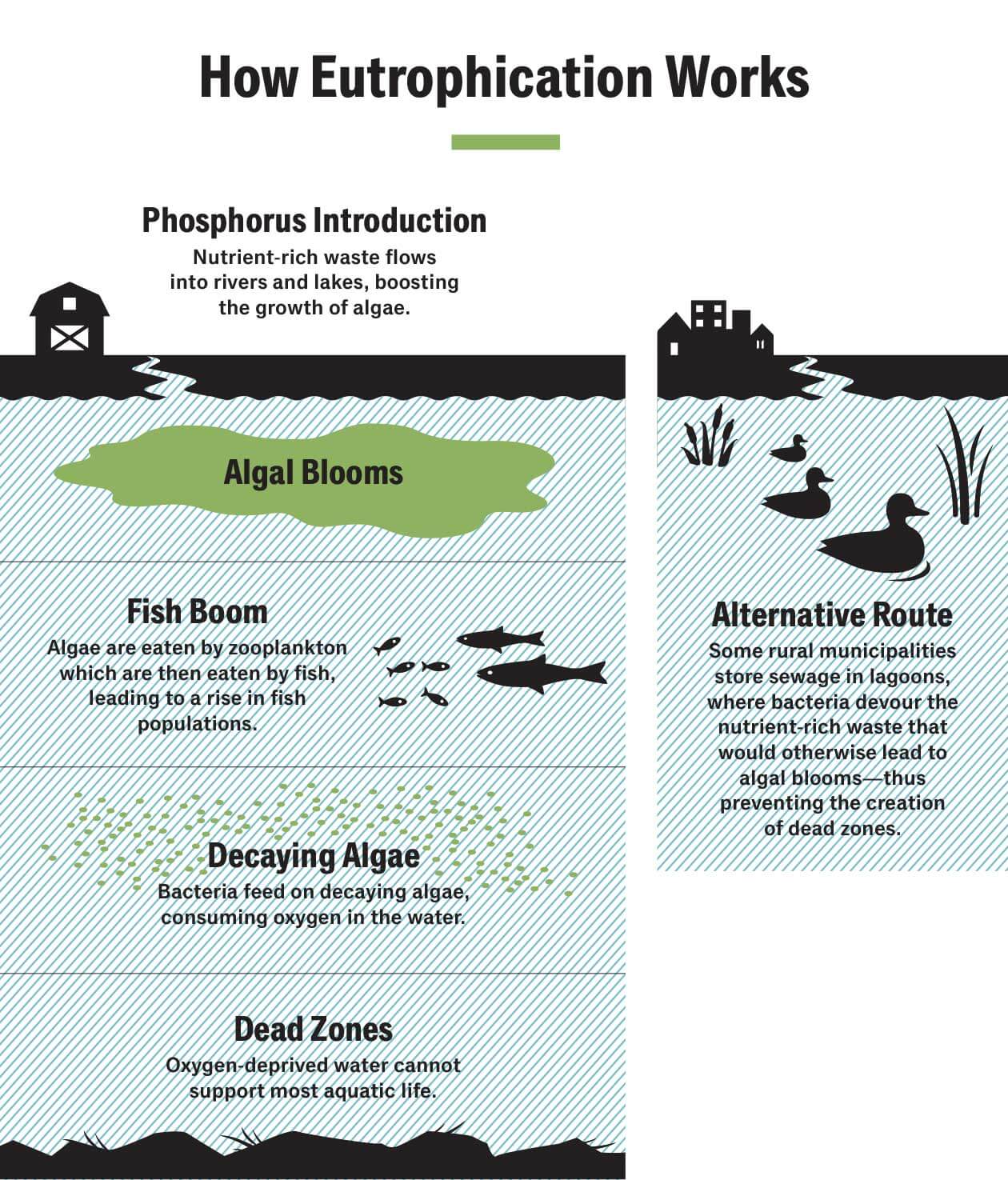

Bob Hecky, a retired professor of lake ecology who has studied eutrophication describes nutrient loading in terms of a “classic arc.” In the beginning, the lake responds by producing more algae. The algae feed zooplankton, which feed small fish, which feed larger fish. At the peak of the arc, the algae create growth in fish populations in the lake. What’s bad for the lake can be wonderful for the fishery. The algal blooms have boosted the numbers of pickerel—the highest-priced fish in Lake Winnipeg, also called walleye. The only problems are that algae make the nets heavy and render them visible underwater.

But the rise in fish populations is only the middle stage of eutrophication. Severe nutrient loading produces more algae than the food web can handle. And as the algae die, they feed bacteria that consume the oxygen in the water, starting at the bottom of the lake. This process leads to the dead zones, or pockets of low oxygen, that may be appearing in Lake Winnipeg.

Because the dead zones appear closer to the bottom of the lake—wind and waves don’t mix the oxygen below a certain depth—species that prefer the colder, deeper waters lose their habitat. Those in the warmer upper waters thrive. This effect is especially pronounced in East Africa’s Lake Victoria, which has one of the worst eutrophication problems on the planet, as well as a large freshwater fishery. Today, most of the fish live in the upper twenty-five or thirty metres of Lake Victoria, while the bottom thirty metres are almost completely devoid of life. If Lake Victoria’s fish population were to collapse, so too would an important source of employment.

Since Lake Winnipeg isn’t deep enough to sustain a consistent dead zone, Karen Scott argues, the notion of a “dead lake” doesn’t apply. If anything, the reverse is true: if algae were a cash crop, the lake would be the most productive farm in Manitoba.

The sky was grey and spitting the day Mike Paterson and I crawled into a small boat and motored out to see Lake 227, an important spot for global eutrophication studies. Paterson has been working at the International Institute for Sustainable Development–Experimental Lakes Area (IISD-ELA) since the early ’90s, and he’s spent much of that time researching the effects of nutrient loading.

In 1968, the Ontario government set aside forty-six pristine freshwater lakes (and their watersheds) in northwestern Ontario and handed them over to research scientists, who promptly set about dumping in nutrients. The aim of the project was to perform whole-lake ecosystem studies. In a famous example, they divided one of the lakes in two, added phosphorus to one half, and found that algae bloomed only there. At the time, eutrophication in the Great Lakes was creating a large dead zone and threatening the fish populations. Many scientists attributed the growth of algae to phosphates, which had been traced, in part, to detergents flushed into the lake from nearby cities. The detergent companies pushed back by casting doubt on the science, suggesting that other nutrients—such as nitrogen or carbon—could be the culprit. But thanks to the IISD-ELA, eutrophication researchers had all the proof they needed.

The IISD-ELA includes about fifteen plain buildings at the end of a thirty-kilometre-long gravel road that roller-coasters through a pine forest. The lakes set aside by the organization have bedrock bottoms that prevent the water from leaching into the earth, making them ideal for controlled studies. Lake 227 could have been built in a laboratory: a circle about 250 metres in diameter, it’s easy to study and easy to manage.

The rain misted Paterson’s glasses as we skimmed across Lake 468—more commonly called Roddy Lake—and then tramped in our rubber boots along a short path to Lake 305, where we climbed into another motorboat and continued our journey Lake 227 is reachable mostly by way of these other connecting lakes, which are kept unpolluted as references for other experiments.

“Lake 227 may be the least well-known and most well-studied lake in the world,” Paterson had told me earlier as we dragged on our heavy rain gear at the lab. More than 200 published papers have used data from Lake 227 over the last five decades. According to Paterson, a Czech scientist once visited, claiming that the research had been his inspiration to study lakes. When he laid eyes on the lake, he fell to his knees and said, “Now I can die satisfied.”

Twenty minutes after setting out, we docked the boat and climbed a short trail lined with pink lady’s slippers. Two University of Manitoba grad students were waiting for us at the lake. A man and a woman in their mid-twenties, the pair were packed inside heavy rain-repellent costumes, but somehow managed to look cheerful, if a little sweaty. The researchers had come to perform a simple task that had been conducted every week during the ice-free season for the past forty-eight years: pour some form of phosphorus into the water. Phosphorus is “pure plant food in its most bioavailable form,” Paterson says. “It’s like steak for algae.” But the element is also versatile: it can nourish a potato, or a pig, or a bit of phytoplankton, or a human. Our reliance on phosphorus is the reason eutrophication is a global problem, affecting many thousands of lakes.

In 1669, a German alchemist named Hennig Brand tried to make the Philosopher’s Stone by distilling urine, and instead produced the first tiny sample of white phosphorus—which was later discovered to be a vital ingredient in all fertilizers, including guano. By the first decades of the nineteenth century, the trade in seabird guano was booming, as farmers in Europe and North America spread more and more on their fields. The guano islands of Peru were heavily mined for the stuff and the mountains of seabird excrement started to shrink. Luckily, by the beginning of the twentieth century, scientists had learned how to extract phosphate from rocks.

The abundance of phosphates made possible the modern intensive agricultural practices that allow farmers to achieve greater yields than manure-dependent farmers in the past could have dreamed of. Phosphates also changed farming from a relatively closed system—nutrient travels from crop to animal to manure and back again—to a more open one. Now we pull phosphorus out of the earth and briefly employ it before it travels out the other side of the human ecosystem, ending up in lakes and oceans.

Once detergent companies had been forced to reduce phosphate use, and city wastewater systems had been updated, the Great Lakes saw an eventual reduction in algae levels. But it was a short-lived victory. The algae have returned in force, creating dead zones in Lake Erie. This time, the phosphorus comes primarily from the intensive agricultural practices that produce our food—not from our soap. For many scientists, the hope lies in closing the phosphorus loop.

Rick gamble is the mayor of Dunnottar, a small cottage community on the west side of Lake Winnipeg, near the bottom of the south basin. Rural municipalities often store sewage in lagoons at the outskirts of town, leaving it to sit so that bacteria can devour the organic particles. Although rudimentary, the system works pretty well. It just doesn’t always remove all the nutrients.

Gamble and I leaned up against his truck to take in the view. Dunnottar has three oblong lagoons lined up in a row. To see them, we had to drive up a berm and along a narrow lane that rimmed the edge. In one of the lagoons, the water was dark, like black coffee. Several families of ducks paddled through the tall grass and cattails by the shore, peacefully snacking on insects.

This might be one of the most innovative sewage-treatment facilities in the world. After being cleaned in these lagoons, the water undergoes a quick blast of ultraviolet light to kill any remaining bacteria, and comes out the other side crystal clear and—according to tests—perfectly drinkable. “Not that most people would want to,” says Gamble, laughing.

Before it even reaches the filtration system, however, water from the lagoons seeps through the field via a system of pipes. The grasses take up the nutrients, removing most of the phosphorus and nitrogen. When the grass around the lagoon gets too tall, it is simply mowed, and offcuts are used as compost for a community garden.

At the moment, Dunnottar’s rather rustic treatment process yields cleaner water than some traditional facilities, says Gamble. “They couldn’t touch us,” he brags—and it cost only about $650,000 to install, compared to the millions sometimes necessary for chemical treatment. The achievement might be only a drop in the bucket compared to the tsunami of nutrients flowing in from the prairies every year, but in his modest way, Gamble has managed to close the phosphorus loop for wastewater.

The idea of recycling nutrients has not been lost on other scientists and water-quality advocates. Several organizations are working on ways to build temporary reservoirs and artificial wetlands upriver from Lake Winnipeg in order to hold back the spring runoff that carries so much of the phosphorus that ends up in the lake. Gordon Goldsborough, for example, a wetland researcher at the University of Manitoba, is developing a simple rig that grows cattails on eutrophic lakes.

Constructed out of bread trays and foam, the device floats over deeper waters where cattails can’t normally grow. “It produces biomass and pulls phosphorus out of the environment. If you harvest those plants, you’re taking the phosphorus with them,” says Goldsborough. “It creates a perfect solution.”

Such optimistic gambits are the stock-in-trade of organizations such as the Lake Winnipeg Foundation (LWF), which Gamble, a former construction worker, founded back in the late ’90s. He suspected that some of his neighbours might also be anxious about the algae and want to do something. He started holding meetings; in time, they grew into the LWF. The organization now employs half a dozen people in downtown Winnipeg and is central in the fight against the lake’s eutrophication problem.

Nutrient loading is such a complex issue, and involves so many contributors and stakeholders—Indigenous communities, cottagers, fishermen, farmers, the City of Winnipeg, and other levels of government—that efforts to solve it have consistently been trapped in a cycle of blame shifting. One of the most significant divides is over which is the bigger problem: municipal wastewater or manure runoff. The LWF tries to strike a conciliatory tone between these warring perspectives, while building public awareness.

The real challenge is to take a complicated problem that most people find overwhelming and make it simple enough for people to believe it’s worth caring about—all without pointing fingers or overstating it.

In 2013, a CBC story declared that Lake Winnipeg was “the world’s most threatened lake”—other media outlets ran similar headlines. But the hyperbole struck Karen Scott as suspicious. After looking around online, she found that the headlines misstated an announcement that had been issued by an organization called the Global Nature Fund, which currently includes 106 lakes in its worldwide stewardship program. Of those, only four had been submitted for the “threatened lake of the year” laurels. Conclusion: Lake Winnipeg is absolutely not the world’s most threatened lake, and never has been.

The panic over zebra mussels is, for Scott, another example of media hype. In 2015, Pip called the lake a “lost cause” because of the incursion of the mollusc over the last few years—her phrase was used as a headline by Global News. But while zebra mussels can be bad news, Scott says, they do not spell doom. No one denies that they can be devastating. They filter particulates out of the water so it becomes clearer; darkness-loving species, such as pickerel, are pushed farther down, crowding the fish already there into a smaller and smaller area. The zebra mussels also consume algae-eating plankton, leading to more blooms. And because they are such intense filter feeders, they accumulate toxins in their tissues, becoming a danger to the fish and birds that eat them.

The changes wrought by zebra mussels are so profound that Scott thinks we need to view Lake Winnipeg as a new ecosystem and research it accordingly—but not act as if it’s facing Judgment Day.

Over the past decade, the debate over how to fix Lake Winnipeg has latched onto a specific—and, some say, too convenient—target: hogs. Over the course of a year, Manitoba supports a population of nearly 8 million swine, many of which are destined to be devoured in other provinces as well as in the United States. Hogs are prolific shitters. The province, which has a human population of roughly 1.28 million, must therefore manage the waste output of animals that produce up to four times as much excrement as humans. To achieve this feat, they put it all in holding ponds.

Peter Leavitt, a biologist from the University of Regina in Saskatchewan, argues that the rise in algal blooms coincides with the rise of agriculture in the province. Leavitt was commissioned by the former NDP government in Manitoba to report on changes in Lake Winnipeg’s water quality, and his findings were a factor in the creation of the Save Lake Winnipeg Act in 2011. The problem, Leavitt explains, is that a heavy snowmelt and an overland spring flood can carry that phosphorus-rich pig manure into the streams and rivers that feed the lake. In sum: “You’ve got too many damn pigs and cattle.”

In 2008, the province introduced restrictions on the building of new hog barns and manure-storage facilities, in large part to limit the amount of hog manure travelling to the lake. By 2011, when the moratorium was expanded, the number of hog farms in Manitoba had diminished by more than half. Manitoba farmers have been frustrated by the economic impediments. After all, there’s a huge and hungry market to feed. That year, Don Flaten, a soil scientist, reassured farmers at a pork-industry event that phosphorus runoff from their hog farms accounted for only a small percentage of the nutrients flowing into the lake.

This past March, the hog farmers were vindicated. Manitoba’s Progressive Conservative government introduced the Red Tape Reduction and Government Efficiency Act, which, among other things, makes it easier for hog producers to expand their operations. Policy changes such as this highlight the gridlock in the environmental movement. The farmers are meeting a genuine demand, and the government is serving an economically viable industry. They may be harming the lake—whether inadvertently or carelessly—but they are also reflecting our society and its concerns and appetites. Which is why Dave Courchene, a prominent Anishinaabe elder, doesn’t believe that meaningful change will come only from the top. “Until we find the way to have a much more sacred relationship with the land,” he says, “we’re going to continue down this path of destroying the future for our own children.”

On the day we met, he wore a baseball cap over his wavy grey ponytail, and lounged in the booth at a local restaurant, picking at a tray of nachos and cracking jokes. (“We had running water when I was growing up: I ran down to the lake to get the water, and then I ran it home.”) Courchene says that over the course of his life, he has seen Lake Winnipeg transform from a clean source of drinking water into a danger to swimmers and residents. He’s heard every sort of promise and justification along the way. “There’s so much rhetoric that goes on,” he says. “People say the right things, and that’s about all they do.”

Known as Leading Earth Man, Courchene does environmental advocacy work around the world and is the founder of the Turtle Lodge, a healing and cultural centre. In the summer of 2015, elders, grandmothers, and traditional knowledge-keepers from across North America met at Courchene’s home community of Sagkeeng First Nation to participate in a water ceremony on behalf of Lake Winnipeg. Many brought jars of water from lakes and river systems in their own communities and carried them out into the lake in a procession of small motorboats and pontoons.

Nature’s laws are self-enforcing, Courchene says, and you reap what you sow: “If you put love into the water, you get love back. If you put pollutants in the water, then that’s what you get back. I believe there’s a lot of hope—it’s just a matter of continuing the work that’s being done to create greater awareness.”

On my last day travelling around Lake Manitoba, I visit Pip. She lives alone at the end of a narrow lane through a thick stand of trees that is surrounded on all sides by farmland. In the late ’90s, Pip registered her forty acres as a conservation site and allowed natural vegetation to return; in a fifteen-acre field at the back, she planted 6,000 trees. The decision didn’t make her popular with her neighbours.

As we talk, Pip once again reviews the problems in Lake Winnipeg: the toxins, the wetland destruction, the rapacious zebra mussels. The list goes on and on, like an incantation. Unlike the campaigns of studied urgency and optimism run by organizations such as the LWF, Pip’s gloomy take on the lake isn’t calculated. She’s been listening to cautious statements and hopeful solutions for the last five decades, and despite all that calibrated energy, little has changed.

“I don’t see that lake being rescued, certainly not in my lifetime,” she concludes. “You would have to get all of these different contributors to the problem to stop doing what they’re doing, and that’s not going to happen.”

I say goodbye to Pip and drive to Hillside Beach. It’s a hot day, and sunbathers have staked out plots for their lounge chairs, coolers, dogs, and toddlers. Although murky, the water was just the right temperature for a swim. I notice a woman wading with her two children. The younger one bends his face down to the water, just a few feet from where it ripples gently against the shore. “Don’t drink the water,” the mother says sharply. “It’s yucky.”

Correction: An earlier version of the article misstated the manner and reasons for which Dr. Eva Pip left her position at the University of Winnipeg. The Walrus regrets the error.