As a commercial artist, Steve McDonald often made big, elaborate drawings of buildings and street scenes. His two young daughters, Roxana and Asha, found them fascinating and wanted to keep them. They would be great to colour, they told him. “Go away,” he’d say, sitting in his studio in the Bali jungle. “I’m working.”

Then a client who’d ordered two large and complex prints admitted, at the risk of offending the artist, that he intended to give them to his sons for the same purpose.

“At first, I thought, fine, you’re paying for them,” says McDonald. “And then I thought, maybe there’s something to this.”

Adult colouring is everywhere now—worthy of a curated table at Indigo, and group colouring nights that bring hipsters to venues such as the Gladstone Hotel in Toronto—but back in 2014, it was just taking off. After McDonald began to pitch publishers, a bidding war ensued for one of his projects. He then signed with San Francisco’s Chronicle Books for a collection of drawings of urban scenes.

That book, Fantastic Cities, has now been published in two dozen countries. “It’s a bit of a magical story, obviously,” he says of the volume’s success. He figured it might sell a few thousand copies. He had no idea he was on the cusp of a breaking trend. By the end of 2016, Fantastic Cities had sold more than half a million copies worldwide. It was number six on BookNet’s Canadian non-fiction list for 2015, beating out two volumes by Chris Hadfield. “We thought it was a blip,” McDonald says. But sales kept building.

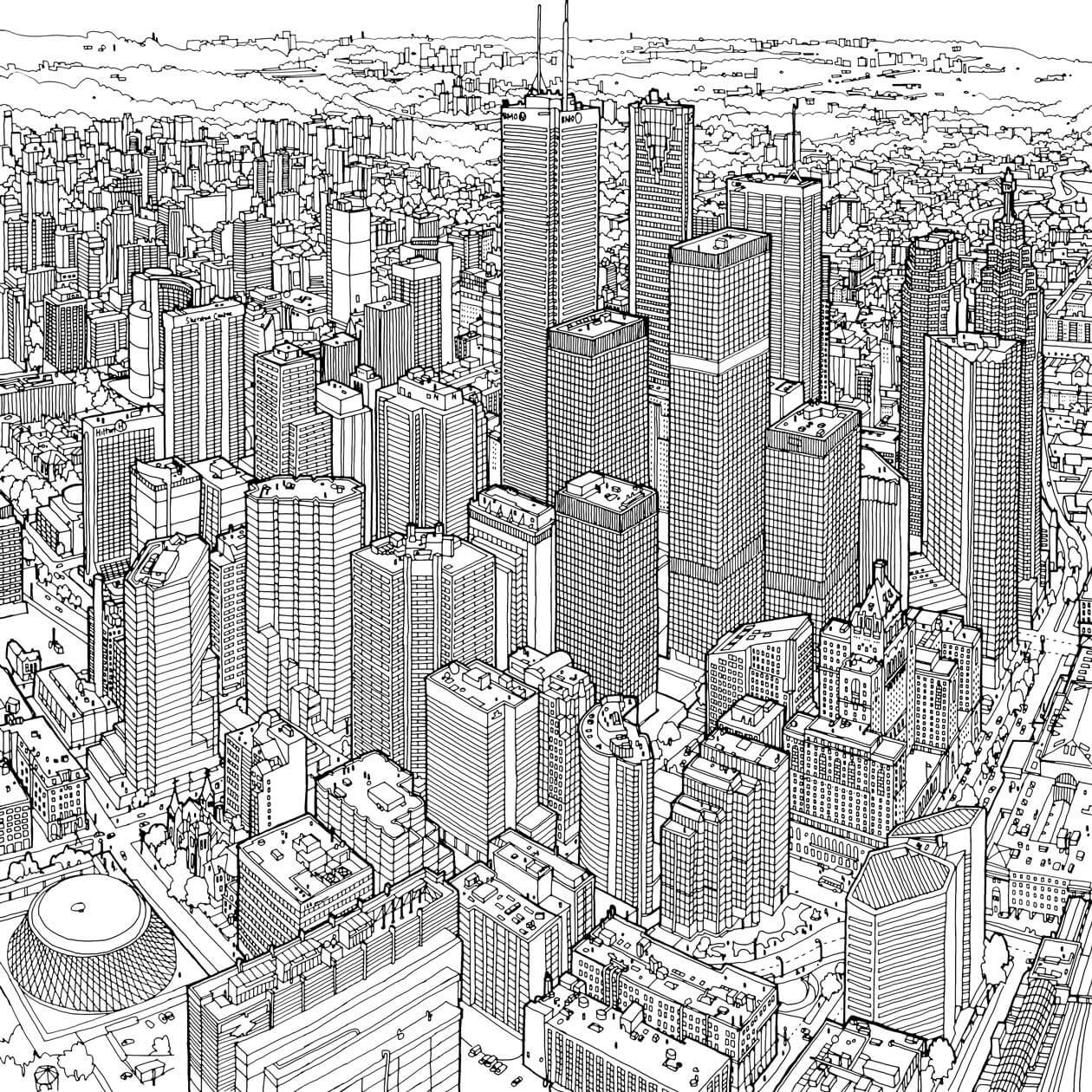

The cities in Fantastic Cities are real. McDonald studied aerial photographs of such places as Bremen, Germany; Stockholm, Sweden; Himeji, Japan; Mont-Saint-Michel, France; and even the shipyards of Collingwood, Ontario. He then created line drawings using either pen and ink on paper, or a stylus on an oversized computer tablet. The drawing of Bremen, for example, shows row after row after row of urban residential streets from a bird’s-eye view. The design is rhythmic and detailed; a close look reveals windows and skylights no bigger than grains of rice. But no house is the same as any other. The drawings have clearly been hand-drawn—they’re not mechanical, not the products of apps or programs. The actual architecture of Bremen (and pretty much any urban place in the world) seems banal and repetitive until you get up close and see, for better or worse, the human touch.

The drawing of Guanajuato, Mexico, is claustrophobic: we get the sense that the city might’ve started anywhere, a dart thrown on a map, and then built itself outward from there (house by house) until it stopped for some reason, but not before creating a dense, organic pattern of makeshift architecture—like a beehive built by bees that forgot what honeycombs look like. McDonald’s line drawing is crowded and confusing, probably much like Guanajuato itself. There are no people in the picture—just what the people have made. “I want you to be mesmerized by the complexity,” he says, “but also think, whoa, these are patterns of habitation we created. It starts to get a feel of, okay, this is nuts.”

That’s ambitious. I mean, it’s a colouring book. Traditionally, the genre’s goal has not been to contemplate mortal hubris and that which humans wrought. The point was to colour inside the lines and not make a mess. But, in fairness, adult colouring books—the good ones—serve a different purpose: they take your mind off stuff. They are more in the spirit of the paint-by-number sets of the 1950s, which supplied an image already divided up into sections, and paints that could be applied according to a predetermined code. Or DoodleArt of the 1970s, trippy black-and-white designs in large poster-sized prints that were meant to be coloured in with markers, and became a favourite of stoned adults. Or crochet kits, or model railroads, or anything that calls for tight focus and repetitive, but still arguably constructive, activity. They go back to Byzantine mosaic art or the rosary: you worked at something not intellectually demanding for a period of time and felt better.

But is it art? Steve McDonald went to art school. After graduating in 1993, he co-founded a group of landscape painters with the palindromic name of Drawnonward. Their idea was to reveal “that which is universal to all human experience, irrelevant of time, economy, or culture—our landscape.” The size of the group was limited to between six and ten members, but they tried to avoid having precisely seven, so as to sidestep comparisons with that other group of Canadian landscape artists. McDonald learned his craft. But after almost twenty years, he left. “I felt pigeonholed,” he says, “because there was this expectation people would see beautiful white pines in oils, and I was deviating from that. I wanted to bust out and start drawing stuff that had nothing to do with their mandate,” he says. “Favelas in Brazil or parking lots in Mexico. There was no way to fit that into their mandate.”

He drew buildings and cities, both real and imagined. He was influenced now not by A.Y. Jackson, a founding member of the Group of Seven, but by such graphic and comic artists as Jean Giraud, known as Moebius, and such writers as Italo Calvino. “I’m a big fan of Calvino’s work,” he says. “He creates these magical fantastical worlds, slightly beyond reality”—which is as good a way as any to describe the slightly off-balance feel of McDonald’s cities in this colouring book: they look real and fairy tale–like at the same time, as if they owe much to a technical truth but even more to the artist’s imagination. These are cities the way McDonald wishes they looked. So, yes, it’s art.

The harder question to answer is this: Does colouring a Steve McDonald drawing count as art? If not, why are people buying these books by the hundreds of thousands, not just at art stores but at grocery stores and Shoppers Drug Mart? There are Game of Thrones colouring books, Doctor Who colouring books, unicorn-related colouring books, human anatomy colouring books. “It’s just a colouring book,” he says, “but the idea is that there’s a void in society—there’s a void of ideas to legitimize getting offline. You’re just colouring someone else’s drawing. That’s not artistic. But it is! You pick up a guitar—how do you learn to play? You learn Neil Young’s ‘Heart of Gold.’”

So adult colouring is not art, but it is a cover version of art—something creative to do until art comes along. McDonald shows me some examples of the colouring sent to him by his fans: there’s a dark vision of a metropolis submerged in water and patrolled by sharks. For some, McDonald’s line drawings are just starting points for weirder, more expansive and original graphic ideas. “I’m not giving you the rules just to fill them in. Referring to one of his fan colourers, he says, “she changes the weather in the pictures. She puts vines on buildings and everything, makes it post-apocalyptic.” I recall the same kind of thing happening with paint-by-numbers: you would paint Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy orange and give him red devil eyes just to be subversive, and all due respect to the creators of Casper the Friendly Ghost colouring books, it was liberating to go outside the lines.

Does that explain the popularity of adult colouring? Sanctioned subversion? Structured freedom? Partly. But it also has to do with what wins Calvino readers for his fiction: not everything has to be heavy and serious. Lightness is a value. Before, McDonald says, he was painting for gallery walls for rich people to buy. Now his work is more democratic, cheaper, and, once you get past the impulse to frame it as commentary on patterns of human habitation, refreshingly goofy. “To be allowed to do stuff that’s fun and creative and silly and maybe not that important or not that hard, we don’t get permission to do that all the time.”