The hut at the Hudson’s Bay Company post was dim and cluttered with harpoons, fishing nets, sled-dog harnesses, and sealskin boots. Seated on a box, the American prospector Robert Flaherty listened to two men speak a language he didn’t understand. One was George Wetalltok, an Inuit man in his fifties who had been employed as a pilot on HBC ships. The year was 1909, and Flaherty had stopped to restock supplies on Charlton Island before pushing further north along the coast, crossing rivers that gushed fresh water into southeastern Hudson Bay.

“Wetalltok is full of stories of the North, sir,” said a translator named Johnny Miller. “He has just been telling me what a long time it is since he was there.”

“What part of the North does he come from, Johnny?” asked Flaherty.

“He says his country is far out from the coast—on islands out at sea,” said the translator.

Flaherty pulled out a map of the Hudson Bay area and offered it to Wetalltok. The Inuit man examined the paper carefully, initially at a loss. Then he pointed to a small cluster of dotted-line circles, marked on the map as unexplored but named: the Belcher Islands.

“Wetalltok says his land is here, sir, where these islands are,” said Miller. “But the way the white man draws them is crazy. It’s a big land that’s there.”

Flaherty had heard rumours of people from these islands who crossed the ice when it formed a bridge to the coast in February and March and visited communities along the rim of Hudson Bay. These hunters would materialize through the fog wearing clothing not made from seal or caribou hide but strange heavy parkas made from the feathered skins of ducks. They looked like flightless birds.

During more than 300 years of exploration and cartography across the Canadian Arctic, the Belcher Islands remained little more than a name. The crude squiggles or dots made by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century mapmakers morphed or even vanished altogether, little more than token approximations based on stories. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, the most detailed map that included the Belchers was an 1884 British admiralty chart marked with two abstract clumps of circles—as if the cartographer knew there was something there, but had no clue of shape or feature or size. The largest island appeared just ten kilometres long.

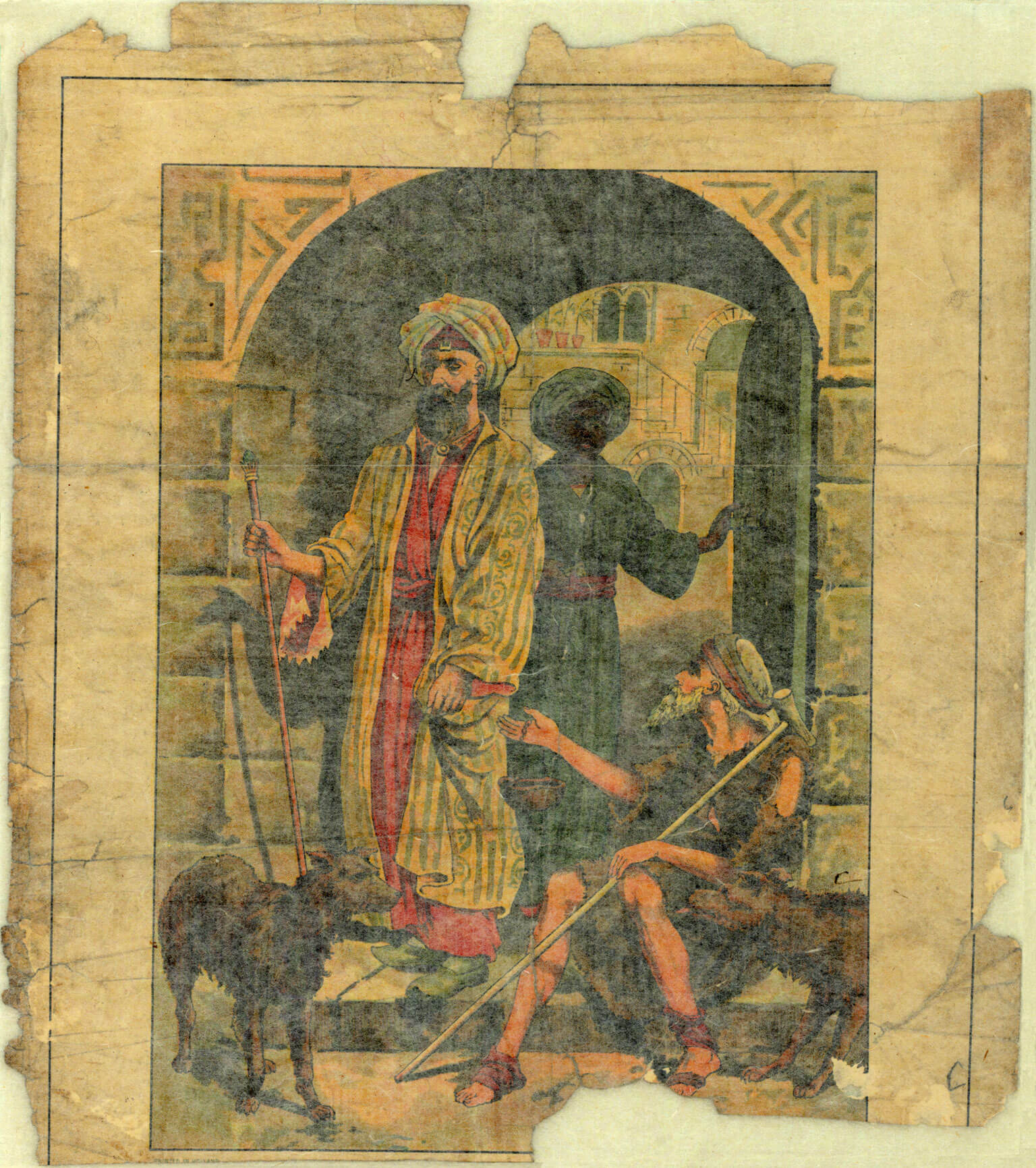

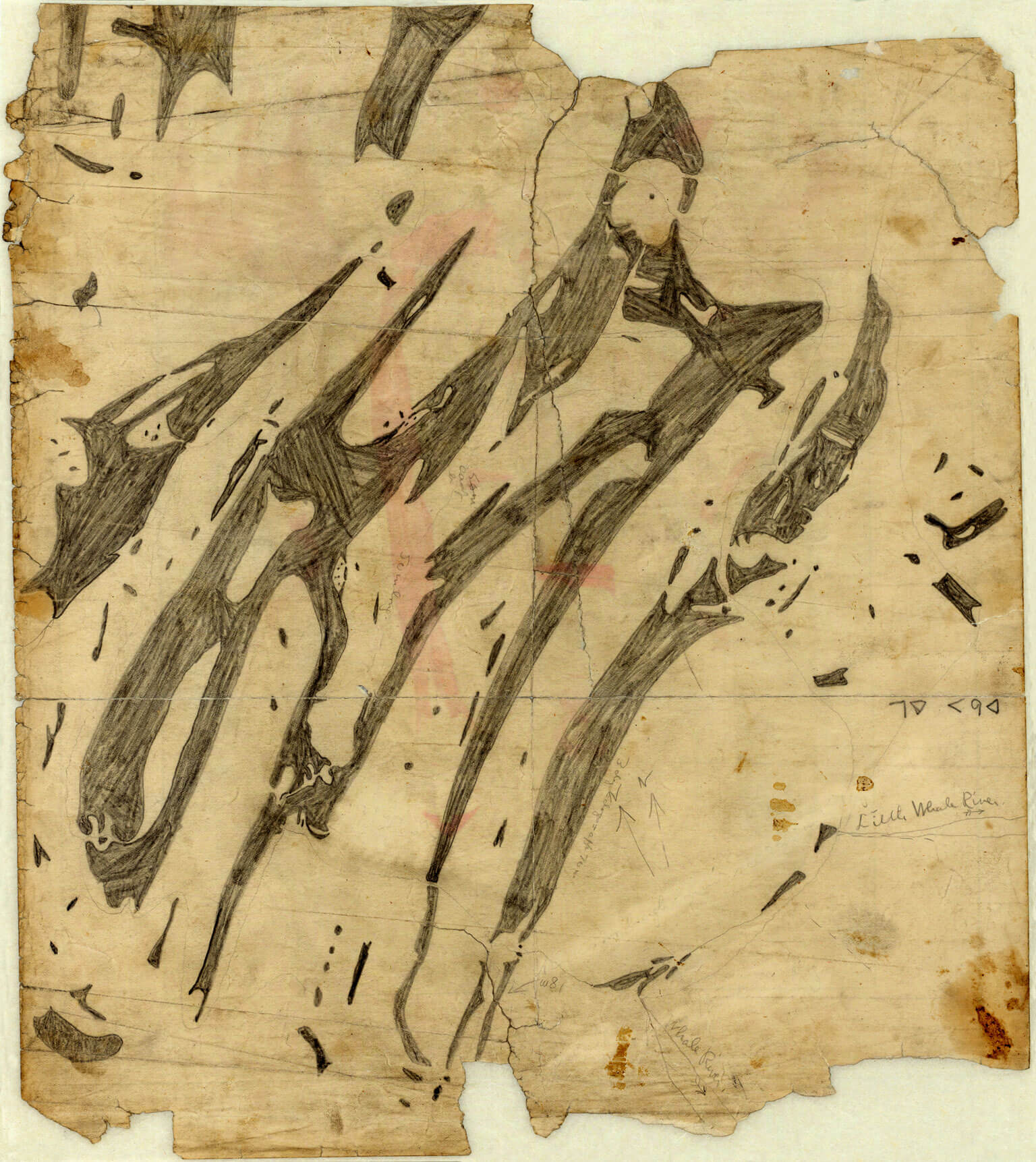

Wetalltok was telling a different story. He opened a sea chest packed with ivory carvings, tools, and odds-and-ends, and removed a single piece of paper, torn at the edges, stained and yellowed with use, and handed it to Flaherty. The prospector examined the colourful scene that was illustrated on the missionary lithograph: the bearded Good Samaritan, wearing a turban and patterned robes in red and green, stepping through an archway with a pauper at his feet. Christian propaganda.

“No,” said Miller. “It’s this side he wants you to look at.”

On the reverse, Wetalltok had drawn a map that depicted a fragmented archipelago of sinuous islands shaded in with pencil. Not a single feature on land—no forest or mountain or settlement—had been identified. Rather Wetalltok had taken particular note of the water features by outlining detailed harbours, plunging bays, numerous lakes, and dozens of minor offshore islets. He had drawn 106 islands, well shy of the approximately 1,500 in total, but the tattered piece of paper was the most comprehensive and accurate map of the Belcher Islands at the time. He told Flaherty that it took many days to kayak from southern to northern tip, meaning the archipelago was much larger than ever estimated, at approximately 150 kilometres long.

Flaherty didn’t believe the Inuit hunter who sat before him. How could European ships and explorers have navigated and charted the region for centuries without an accurate understanding of the largest archipelago in Hudson Bay? And that it lay less than 100 kilometres from the coast? It was impossible, the prospector said.

Wetalltok smiled. “Yes, it was possible. The white man doesn’t know everything.”

A March wind drifts across the Belcher Islands laden with micro ice crystals that glisten in the air and sting my cheeks. At the top of a rocky outcropping at the centre of the town of Sanikiluaq, I shield my eyes and scan the pebble-and-ice streets looking for motion. The land appears to be on the move.

Apart from a few low hills of snow-covered rock, the nearly 3,000-square-kilometre archipelago is featureless during the long winter that settles like a heavy blanket across southeastern Hudson Bay. No greenery protrudes during the season of desolate whites and blues, when all life fights a constant battle, if not to survive, then just to stay warm.

In the distance I spot it: a snowmobile cruising down from the single-strip airport that’s perched on a ridge just outside town. Joel Heath is driving cautiously—not accelerating too quickly nor turning too sharply—to keep steady the Google Street View camera ratchet-strapped to the machine’s frame behind him.

Heath is on a trial run to test the camera, the stability of its metre-tall custom mount, and how its batteries fare in minus-thirty-five-degree conditions. But he’s also mapping the streets of the community. Every two-and-a-half seconds, the fifteen cameras pointing out from the green, bug-eyed orb silently fire: ice road, cemetery in a snow field, speckled rock, brightly painted houses, frozen lake, foggy horizon. Over a half-hour drive, the camera will capture more than 10,000 images, which will be sent 3,791 kilometres from Sanikiluaq to San Francisco, where Google technicians will splice them together to create a 360-degree digital map viewable by anyone with an Internet connection, anywhere in the world.

Above me, two flags flutter atop a five-metre-tall steel flagpole: The Maple Leaf, and the territorial flag of Nunavut, half yellow at the hoist and half white at the fly with a red inuksuk at centre and a blue pentacle star in one corner. The stone cairn, a ubiquitous symbol of the Canadian Arctic, denotes navigation by day, while the North Star represents navigation by night. The flag’s primary colours stand for land, sea, and sky, but today there is no distinction between the three, just a continuous plane of white land and white ice blending seamlessly into white sky.

Through the din of the wind, I hear something overhead: a strange cross between a squawk and a coo. But when I look up, I can’t spot the source, as the bird—an eider duck—remains hidden in the fog. It’s not the inuksuk or the North Star but the eider duck that is the symbol of the Belcher Islands, a symbol and a resource under threat as the water-and-ice ecosystem is being radically redefined. And the Belcher Inuit, a people who rely on the eiders and who for so long were left off the map, are now turning to digital cartography not only to monitor their shifting environment but also to spread their story beyond the shorelines, and beyond the bay.

The Street View camera continues to take pictures as Heath turns his snowmobile sharply off the main road onto a track I cannot see. Sanikiluaq is a town without street names, where a Ski-Doo trail becomes a single-lane road and then fades into a hunting path. In a seamless transition, Heath traverses the hidden shoreline and is out onto the ice-locked inlet.

A century after Flaherty used Wetalltok’s scribbled chart to navigate and overwinter on the archipelago in 1915, a new kind of map is being drawn of the Belcher Islands.

Once inside his home-cum-office, Heath pulls his parka over his head and hangs it on a peg by the door. The knee-length garment looks heavier than it is, stuffed with eiderdown. “It’s is the warmest feather in the world,” Heath says. “It’s the symbol for working with nature, for energy solutions, staying warm in winter, and working with the seasons.” This is Heath’s thirteenth winter on the Belchers: Beginning in 2002, he spent weeks at a time camped in a plywood observation box on the sea ice conducting field research for a Ph.D. on how eider ducks survive.

Above the walrus and the polar bear, the eider heads the faunal pantheon of the Belcher Island Inuit. In the mid-nineteenth century, the archipelago’s caribou population nearly vanished, likely from a particularly severe winter that kept lichen, the herds’ main sustenance, frozen well into the spring. The islanders turned to the plentiful ducks as a necessary food source. Instead of migrating south like other species, eiders overwinter around the islands, and remain a constant resource for the Inuit. But it’s the down from eiders that has since garnered worldwide acclaim—not plucked from live birds, but carefully and sustainably harvested from nests during the summer.

But for Heath, the eider duck is also the “canary in the coal mine” for environmental change in Hudson Bay. Tacked on the wall of his office is a nautical map of the bay that shows the details of the Belcher Islands and the provincial and territorial boundaries. Nunavut not only extends less than 1,000 kilometres from the North Pole, but also dips well south of 60° to include every island in Hudson Bay, regardless of proximity to Manitoba, Ontario, or Quebec.

With three provinces and a territory, plus numerous land-claim regions and government departments, the Belcher Islands lie at the heart of a jurisdictional Venn diagram. “When something happens, who is responsible? Which of those twenty jurisdictions picks up the ball?” Heath asks. “In a way, it’s the forgotten region of Canada.”

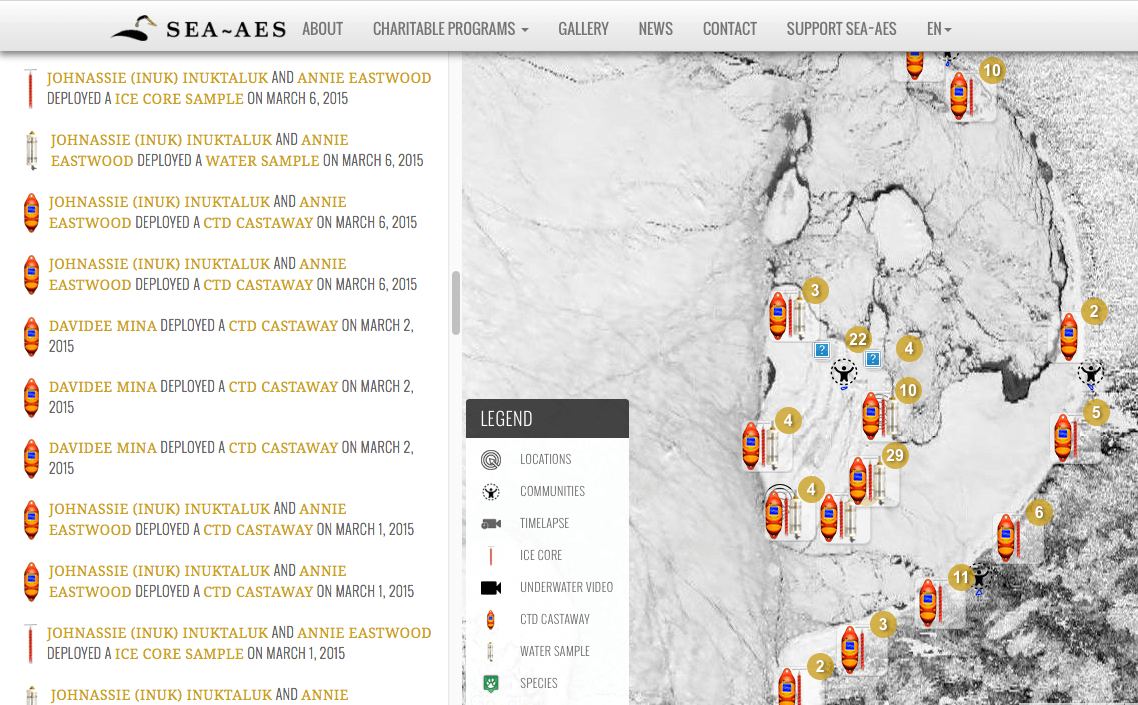

Following the success of his acclaimed 2011 documentary, People of a Feather, Heath formed the Arctic Eider Society, a non-profit that monitors sea-ice ecosystems, connects communities in the region, and builds environmental stewardship. Heath began envisioning a map that could do all three, so he invited Google’s Earth Outreach program (which partners with small organizations to map a cause, such as deforestation in Brazil or polar bear movements in Manitoba) not only to add parts of the Belcher Islands to Street View but also to create the baseline map for the AES. The result is the newly launched Interactive Knowledge Mapping Platform, or IK-Map: a single digital source to mark resources, navigational points, cultural landmarks, as well as scientific measurements, photographs, and videos.

“This is raw data that can be interpreted with both scientific and Inuit knowledge, and the platform is a way to bring those two together,” Heath says. “The best way to learn, the Inuit way of learning, is to be there to observe and to watch.” Hunters from Sanikiluaq, and four communities along the coast of Quebec, are collecting and uploading observations, such as changes in animal populations or unusual fluctuations of the floe edge. Each hunter has a social media–like profile to record and discuss their observations, using icons for a dozen species of wildlife and the same number of ice features.

Heath hopes the IK-Map not only connects communities, but also illustrates the undeniable story of dramatic ecological change in the sea-ice ecosystem of southeastern Hudson Bay, on which the Belcher Island Inuit, and the eider ducks, depend.

Lucassie Arragutainaq has the dark ruddy cheeks and nose of a man who has spent decades out in the cold. He heads the local Hunters and Trappers Association and works closely with the AES. He grew up moving around the archipelago, he tells me. “People used to live in camps, here and there. They never used to stay in one place. We moved by the season—a winter community, a spring community, a fall community.” Today, the only permanent settlement on the islands is Sanikiluaq, a cluster of around 100 houses wedged between a lake and a wide, sheltered harbour.

Arragutainaq learned to hunt and navigate from his father. There are four kinds of waves, his father taught him, and knowing each can help plot a safe course through thick fog while kayaking or boating. Similar to clouds, the formation of waves is based on a multitude of factors: recent wind direction, weather patterns, currents, season. If you can identify the particular wave, you can find north.

“In winter it’s the same thing,” he says. “When did the ice freeze? How did it freeze? What was the temperature when it froze? Where was the wind blowing from when the ice froze?” Including star charts for nighttime navigation, Arragutainaq has developed two overlapping mental maps of the islands, one for summer and one for winter. Rather than depicting road names, they show him where to find food. As the seasons shift, Arragutainaq is constantly updating and modifying his invisible maps.

But something changed in the late 1990s. Arragutainaq was one of many hunters who began to notice that the ice that surrounds the islands and fills the plunging bays for nearly ten months of the year was freezing earlier and thicker, and building up differently; it was softer in places, and less predictable. Off the southern coastlines the ice began forming as it does on a lake: clearer and more brittle.

“We wanted to know what was happening in Hudson Bay, with the hydroelectric projects on the mainland,” says Arragutainaq. “We were seeing things changing and we wanted to know what was going on.”

One of the world’s largest hydroelectric systems is the James Bay Project in the La Grande River basin in northern Quebec. Its eight generating stations produce enough terawatts to power a small European country, such as Belgium or the Netherlands. In 2002, the federal government, the government of Quebec, and the Grand Council of the Crees signed an agreement known as “La Paix des braves,” leading to the construction of three more generating stations, and the diversion of the Rupert River—one of the largest in the province—in 2009. With 40 percent of Canada’s freshwater runoff flowing into Hudson Bay, the Belcher Islands lie in the direct path of what is expelled from rivers in northern Quebec and Ontario.

“Sanikiluaq is the only community that is in the middle of all that,” Arragutainaq says. “But we don’t have any say.”

The changing ice conditions were causing mass entrapments of eiders at polynyas—pockets of open water in sea ice that are vital to many species’ survival—that were shrinking or freezing over entirely. A common memory of elders in Sanikiluaq is that one year there were “more dead eiders than pebbles on the beach.” The population decreased by an estimated 75 percent, and the collection and export of eiderdown plummeted—a decline that was enough to shutter the town’s small facility in 2005. According to hunters, the freezing over of polynyas is becoming more common each winter, with dire results. In February 2013, seventy belugas searching for open water to breathe became trapped under this rapidly forming ice. Many died. During that same winter, there was another massive die-off of eiders—the same year that Hydro-Québec recorded their highest energy usage in a decade.

Arragutainaq and the hunters from Sanikiluaq also noticed something curious—a marker of the most visible change to life on and around the Belcher Islands. When a hunter shot a seal the carcass used to float on the surface of the water with its blubber maintaining buoyancy. But the seals started sinking before they could be retrieved; often spotted out of reach well under the hunters’ kayaks or boats. For Arragutainaq, it was simple: “I’ll tell you what I’m seeing, and you tell me why.”

The Arctic Eider Society set out to explain the puzzle of the sinking seals by equipping hunters with CTD instruments to measure the water’s conductivity (or salinity), temperature, and depth. Out on the sea ice, hunters bore holes, lower down sensors, and record data. When the AES mapped and examined the initial results, Heath was astonished: Flowing out from the river network of northern Quebec and Ontario is a twenty-five-metre layer of fresh water that spreads out across southeastern Hudson Bay and around the Belcher Islands.

“The winters where we’re seeing entrapments of birds are the winters that are very cold in the south,” says Heath. “When you look at the plume of fresh water coming from La Grande River, you see more water and for a longer period of time.”

The winter salinity levels in Hudson Bay are typically around thirty parts per million, but hunters are recording levels as low as fifteen parts per million. The scientific findings confirm what hunters have observed for years: They knew the water was changing. The dead seals are sinking through the freshwater layer, and coming to rest at the denser, saltwater layer.

Each point of data—a salinity measurement, a photo of an eider entrapment, a depiction of the floe edge as it changes over time—is being uploaded onto the IK-Map. And work is not only being done in winter, with summer samplings of mussel shells and duck eggs to test for excessive methyl mercury, a common byproduct downstream from hydroelectric dams. Now, whenever hunters from Sanikiluaq go out on the ice they return not just with food, but with data that they upload onto a digital map to ensure that the Belcher Islands are never again ignored.

“You’re gonna freeze,” says Joel Heath, looking me up and down. He chuckles, but is clearly concerned. I’m dressed for the mountains—five layers of merino wool, down, and Gore-Tex on the top; four on the bottom; three pairs of socks—but dangerously underprepared for a day snowmobiling across sea ice to a polynya. Out the window, the sun has begun its low arc across the horizon, burning yellow and feigning warmth.

Heath points to the rack of garments beside the door. I replace my thin outer shell with a pair of thick bib pants and a knee-length pullover parka stuffed with eiderdown and trimmed around the hood with tawny fox fur. I sink my feet into a pair of expedition boots at least two sizes too big. The key to avoiding hypothermia isn’t multiple tight layers, but gaps that trap warm air—like the tiny spaces within a feather. In an instant I’m too hot, and step out into the minus forty-degree dawn.

Outside, a team of three from Google is doing final checks on the Street View camera mounted to the back of Heath’s snowmobile. They have been having trouble turning the device on in the cold, so a few members have tucked spare batteries under their parkas to maintain charge through the day. Four men from Sanikiluaq, the principal community on the islands, are tinkering with their snowmobiles, topping up tanks with a jerry can, and tying a sled behind each machine with four-metre sections of rope. I find my kamatik: a three-metre sled with two-by-six rails and a plywood compartment big enough to fit one or two passengers. The sleds are mainly for hauling gear around town or out on a hunt, but icicles of blood and lumps of blubber on the front slats hint at their main function. I slump into the compartment so that I’m sitting upright on a chunk of foam covered with a caribou skin, and hold on.

Johnassie Ippak, a hunter from town, starts his snowmobile in front of me. Even with my hood cinched tightly, I hear the four other machines rumble to life. Ippak turns in his seat and gives me a thumbs up. The rope goes taught and the kamatik lurches forward. We turn down to what in summer would be a boat launch, past a fishing vessel up on stilts, and drive out onto the frozen harbour.

Ippak maneuvers his snowmobile over ice that is anything but smooth, as if the waves and whitecaps had frozen mid crest. My kamatik shudders as it lurches over ripples like a car over speed bumps. We plunge into a grey fog that hangs low on the ice, with visibility shifting from a few metres to open in an instant. Only the morning sun holds constant through the shifting haze—dead ahead, due east. Despite the fog, an overnight dusting of snow, and the complete lack of physical route markers, Ippak drives with the confidence of someone who knows exactly where to go.

After forty-five minutes, jostling and zigzagging, the first sight of land since leaving town appears to the south: a ridge of black rock like the spine of a great humpback breaching through the ice. Ippak rounds the point and turns south into the frozen channel between Flaherty and Tukarak Islands. When the hunters break to assess the ice conditions and the weather, Ippak tells me the place is called katuk, or passageway, a place where belugas commonly surface. And if we were to cross southeast over two slivers of land, we would enter the largest harbour on the archipelago, Wetalltok Bay. The names are important: The IK-Map not only features locations marked in English but also in Inuktitut.

We push due south for a half hour, until the white expanse is finally broken by a pocket of open blue water about the size of two soccer fields. Ippak slows his snowmobile and stays well back from the floe edge of the polynya; the ice can be unstable here, less than a few centimetres thin.

The team parks the snowmobiles behind a five-metre-tall and thirty-metre-long mound of jagged ice blocks—formed like a mini mountain range when two plates of sea ice are forced together. It’s an ideal place to shelter from the wind, and also to block the support team out of the Street View frame as the camera collects images. I scramble up to the top to get my bearings, and a view over the polynya.

Created by currents pushing sea ice off shore and leaving a pocket behind, or by an upwelling of warmer water, polynyas are crucial to the survival of many arctic species. “They’re an oasis in a desert of ice,” says Heath, who has joined me at the top. “That’s true for the birds to dive down and feed, and for belugas to breathe.” This polynya appears in roughly the same place each year, but is only one of a handful near the islands that is forming consistently.

Through the soft tendrils of steam dancing on the surface, I finally spot them: dozens of eider ducks bobbing gently on the water. Their brown feathers are the only earth tones in a scene of blue and white. In a blink, one disappears with the smallest of splashes to search for sea urchins on the bottom, as another emerges shaking its head.

With the temperature dipping below minus forty, every technology I brought is failing. I take twenty-five pictures with my digital camera before it shuts off, and only one with my iPhone before it gives up. My film camera’s mirror begins sticking, turning 1/1000 of a second exposures into a full one second, useless in these bright conditions. My audio recorder with its two AA batteries won’t even turn on. And then ink in my ballpoint pen freezes. Heath tells me I should have brought a pencil.

Down below, the team of three from Google is troubleshooting similar issues. Despite mapping millions of kilometres of streets, roads, and trails around the world, this is uncharted territory for the company. It’s their first major expedition with the camera to map sea ice, and the first time a floe edge and a polynya will be added to Street View.

The team carefully un-ropes a green tarpaulin to reveal the camera. The device seems to have made the bumpy ride without damage. It has been powered up since we left Sanikiluaq, after the team realized the machine might not turn on in such cold. A member of the Google team removes a battery from the camera’s briefcase-sized computer and replaces it with one kept warm under her parka. Green light.

Joel climbs down from the ice knoll, starts up his snowmobile and drives off to map the polynya.

Behind the ice-hill, the hunters relax. “This place is called ulutsatuk,” says Simeonie Kavik, tracing a large circle in the air with his mittened hand, referring to the rocky land, the bay that holds the polynya, and the ice and the water underneath. The area gets its name because the nearby point resembles an ulu—the crescent moon-shaped Inuit knife used to slice through the meat and blubber of seals and whales. Kavik moved to the Belchers when he was five, where he learned to hunt and navigate from his older brother. He’s now teaching his children how to read the stars, the ice, and the waves.

“Even in a blizzard, we can find our way,” Kavik says. He tells a story about returning from a hunt and being caught in a white-out while out on the ice. The fog closed in around him until he couldn’t see. “I just put my feet down,” he says, kicking a mound of ice until it squeaks and explodes like pulverized Styrofoam. To navigate through the white-out, he used his feet to feel the ripples and folds in the snow for older, harder ice. Knowing the wind direction from the previous few days, he determined the direction of the ridges, and found his way home. While he and other hunters have adopted GPS, until recently physical maps have been non-existent on the Belcher Islands. Over decades spent on the land, ice, and water, Kavik committed the islands to memory. He pauses, trying to find the best way to explain. “You come up here and you would get lost, but if I go to your city, I would get lost too.”

Heath returns from circumnavigating the polynya. He says the camera has captured eiders mid-flight, and an arctic fox trotting around the floe edge with its mouth stained red from a recent feed. All that’s left for the team is to pack up, tuck back into the wooden kamatiks, and return to town before the afternoon winds turn fierce and the temperature dips even lower. The snowmobiles roar to life, spooking a flock of eiders into the bright cerulean sky. The ducks circle overhead once, twice, before returning to the calm surface of their oasis in the ice.

The hunters will visit the polynya again soon, to shoot a seal and drop their instruments down through the ice. But now they will be joined by someone on the other side of the world, navigating the changes of the Belcher Islands with a few clicks of a mouse.

“Where the Streets Have No Names” was written with the support of the mountain and wilderness writing program at the Banff Centre.