Centuries-old brick houses with stepped-gable façades rise higgledy-piggledy from the cobblestone streets of Lüneburg, Germany. Just an hour’s drive southeast of Hamburg, the town is a preserved jewel of medieval architecture. Neat as a pin and burgeoning with early spring greenery, Lüneburg feels oddly disorienting in these early days of May. For hundreds of years it was a salt mining town, and, as the trove beneath the surface was extracted, the earth shifted and the ancient buildings began to tilt. The result is wonky angles and tipsy spires at every turn.

It’s hard for me not to read a seismic metaphor into this shifting landscape. Beneath Lüneburg’s charm, the town has a dark side, one not mentioned in the guidebooks. On the eve of World War II only ten Jewish families lived here, but subtle references take the form of tiny brass memorials engraved with names and set into the paving stones. (Gunter Demnig, an artist from Cologne, fashioned some 48,000 such stolpersteine, or stumbling stones, across Europe in memory of victims of Nazism.) During the war, a concentration camp stood at the centre of town, and a local historian who is trying to lay to rest personal ghosts—his father was a policeman during the war—observes casually that there must still be a hundred people alive who remember it, “but won’t say a word.” Lüneburg was also the site of the famous Belsen Trial in September 1945, the first war crimes trial that prosecuted members of the SS from the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, which was located just an hour’s drive south. And now by an eerie coincidence, Lüneburg is once more hosting a war crimes trial.

Oskar Groening is ninety-three years old and a former SS guard. He has been dubbed the “bookkeeper of Auschwitz” and charged with complicity in the murder of 300,000 Hungarian Jews.

His trial is why I’m here.

Lawyers, witnesses, and members of the public line up patiently to get into the congress hall where the Groening trial is being held. There is a heavy police presence, both outside and in, but the queue is quiet and respectful. Rumour has it that in addition to the airport-style security within, there are plainclothes officers in our midst; in the early days of the trial, a group of Holocaust deniers were removed from the premises. It’s hard to imagine that kind of scene, when all I see is a town and a country trying to live down its past. I’m here to play a small part in helping that process. Perhaps something I say will leave a mark on those in the courtroom, and possibly beyond, about the enormity of losses suffered by families like mine. But I’m filled with trepidation. I’m here to confront my past as well. Though not a survivor, I am nonetheless qualified to testify because of the death of my half-sister in Auschwitz on June 3, 1944. I was asked because a close blood relative of mine died under Groening’s watch.

On May 6, the head judge, Franz Kompisch, announces that Groening is feeling weak and may not be able to make it through the day. The lawyers representing both sides confer with the bench. It’s decided that the historian who was scheduled to present that morning will be bumped, as there will be no afternoon session. I am to follow Ted Bolgar, a spry ninety-year-old who lives in Montreal and is a survivor of Auschwitz-Birkenau, Dachau, and other stations of hell.

Silence reigns except for Bolgar’s words and a simultaneous translation into German. He tells his story. When he speaks of sharing a bowl of soup among six men with no spoon to scoop out the contents, I glance at Groening across the room, dressed neatly in a white shirt and burgundy vest. Bolgar continues in a steady voice, “Because they called us ‘hunds’ and we should eat like dogs. I wish they had treated us as well as they did their dogs.” During a previous session a week earlier, Groening was animatedly taking notes during the testimony. Now he appears gray and exhausted.

Before I came to Lüneburg, I dreaded even the thought of breathing the same air as Groening, an individual who might have gazed with contempt upon members of my family as they emerged, parched and dazed, from a cattle car on the Auschwitz ramp. But delivering my testimony now feels matter-of-fact.

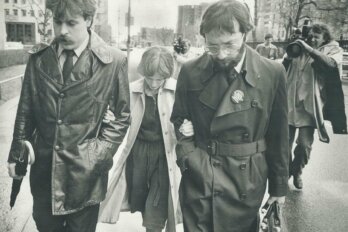

I sit at a small table, with my lawyer, Thomas Walther, beside me. We are directly beneath the dais with the five judges—three professionals in robes, and two lay judges. On a balcony at the back of the room in soundproof boxes the translators ply their trade in German, English, Hebrew, and Hungarian. To our left are eleven lawyers representing fifty-one co-plaintiffs; and off to the side, the two prosecutors. To our right sits Groening, between his two court-appointed lawyers.

Walther entered my life last August. A former judge in Germany, he retired from the bench in 2008 and turned his formidable skills and energy to the cause of bringing Nazi perpetrators still at large to justice. He played a crucial role in the conviction of the Sobibór camp guard John Demjanjuk by a Munich court in 2011, a ruling that established legal precedent for the prosecution of individuals such as Groening as accessories to murder.

When Walther began looking for Canadian co-plaintiffs in the Groening case, a mutual friend put me in touch. His first email to me revealed a persuasive blend of passion and sincerity. In his endearingly fractured English he wrote:

People cannot imagine what it means: 1.000 killed Jews or 3065 Jews in a Train 3 days to Auschwitz or 80 Jews in a cattle car without food and water. They cannot imagine what it means ‘threehundredthousand’ (300.000) murdered Hungarian Jews during the time from May 15 until July 10, 1944 on the place of the death-factory of Auschwitz.

He added that he wanted those who perished “to get back some of their faces, some of their voices . . . and their dignity by being part of the Trial not by the Figure ‘300.000’ but by the co-plaintiffs and their lawyers inside a Trial in front of a German court.”

Walther came to Montreal on three separate occasions this winter. From the initial meeting I trusted him completely. What he was trying to bring home in a courtroom—that the Holocaust is not about the cataloging of numbers, but the recounting of precious individual lives—I had tried to achieve in books I’d written about my parents’ lost families. If he, a non-Jew, could immerse himself so thoroughly in the landscape of the Holocaust, surely it was my responsibility to go to Lüneburg to speak of the shadow family that has furnished my imagination ever since I can remember. Yet the idea of going filled me with deep unease. Germany was where my mother had been a slave, where my uncles and an aunt died, and where the plans for their destruction had been hatched.

Only the closest blood relatives—parent, sibling, child—of victims could testify. I qualified as a witness not because my parents were survivors or that all four of my grandparents and dozens of close family members were murdered in Auschwitz, but because of a little girl named Évike.

Nine months after Walther’s first email, in a silent courtroom, I speak about the short life of Évike Weinberger, my father’s daughter from his first marriage, the half-sister I never knew. I begin my statement, concentrating on the words I prepared back home in Montreal. Walther only has to press my hand once to remind me not to rush.

I am overwhelmed to be present in this courtroom at this moment of historical reckoning. I am here to honour the memory of dozens of members of my family, who perished in Auschwitz. I never imagined that I would travel to Germany. From childhood, I have been familiar with the sound of German place names. Gelsenkirchen, Sömmerda, Glauchau, Buchenwald, Flossenbürg, Bergen-Belsen—these names punctuated stories my parents and their friends told about the war. They were stories of almost unimaginable horror.

I want to thank the court and the German people for the opportunity you are giving me to speak to you about the loss of the many members of my family whom I never knew, because I was born into loss. Unlike most of the other co-plaintiffs, I am not a survivor, but the child of two survivors. I was born after the war in Hungary, to parents who met after the war, and who had each been married to other people before the war. My father Guszav, or Guszti, Weinberger had been married to a woman called Margit, or Mancika, Mandula, and they had a little girl together called Éva Edith, or Évike, Weinberger. I am here to speak primarily about Évike, who would have been my older half-sister had she not perished along with her mother in Auschwitz on June 3, 1944.

How, you might ask, can I speak authentically about someone whom I never knew? It’s a good question. Évike somehow is both my sister and not my sister. She is my sister because she was my father’s daughter, but I clearly could not have a relationship with her of the kind that you have with a sibling with whom you grow up. And yet, Évike has been a singular presence in my life from the time that I came into the world in November 1947 to this day, here in Lüneburg charged with telling you about her short life.

I was about six years old when I first really understood who Évike was, and she was six years old when she was murdered. Over the years, I have become older, but she has stayed six years old. So even though today she would be seventy-seven, in my mind now, she is a child like my grandchildren, not like an older sister at all. I feel a great sense of responsibility towards her, a little girl like so many other children who perished—but also a little girl like nobody else in the world, a unique individual, a unique person.

Évike was born in the city of Debrecen on April 19, 1938, a much desired, much loved only child to Guszti and Mancika. They were prosperous, hard-working, modern Orthodox, educated Jews who were completely integrated into Hungarian life. Guszti and his two brothers were third-generation farmers on an estate in northeastern Hungary, in a village called Vaja. Mancika was an accomplished, well-educated young woman who had attended a finishing school in Switzerland. She was an adoring wife to my father and a devoted mother to Évike.

Évike’s childhood encompassed dark and menacing events in the world: anti-Jewish laws in Hungary, Kristallnacht in Germany and Austria, and the outbreak of war. Guszti was frequently away from home, serving in the special labour battalions into which Hungarian Jewish men were inducted: the munkaszolgálat. Because of this, Évike and Mancika moved to the family estate in Vaja, where my father himself had grown up, and where there also lived my grandparents, and my uncle Pál, his wife, Mary, and their little girl, Marika. Despite the gravity of the situation, life remained relatively normal for them right up until a month before Évike’s sixth birthday, relatively normal until March 19, 1944.

The two little girls, Évike and Marika, were playmates, and they were doted upon by our grandparents and by the other many members of the large extended family, who visited the estate regularly. There are many pictures of the two little girls playing together, and also many photographs showing them with members of the extended family, everybody wearing big smiles.

I have known about Évike ever since I can remember. There were photographs of her on the walls of the apartment in which I grew up in Budapest, including many in the room in which I slept. There were albums, photo albums, of my father’s dead family, and of my mother’s dead family. I have memories of myself from a very young age leafing through the pages of their albums, and asking for the names of the people depicted in the photographs. I even remember my mother smiling and saying I had the same sticking out ears and same bow legs as Évike did, and that we had inherited both these features from our father.

When, many years later, I began to research Journey to Vaja, my book about my father’s family, I learned about the unusual way Guszti and Mancika brought up their little girl. When I interviewed my father’s cousins, they commented on the fact that instead of hiring a nanny and leaving the upbringing of Évike to the nanny and Mancika, my father had wanted to be fully involved in her care. Unlike stereotypical fathers of the 1930s and ’40s, Guszti had bathed the baby, and rocked her and played with her, in a way that was unusual for the time. I recognized the portrait of my father that his cousins painted for me, because he had been the same kind of father to me and my sister, very protective and very involved.

My father was a wonderful storyteller, who loved to talk about the family he had come from. Among my first memories is of him telling me stories about his family—and these were invariably happy stories. He evoked festive occasions on the estate and especially liked to talk about the adventures he and his brothers had growing up on a large farm. Still, even though these were positive stories, he would preface them with the words, “I feel sorry for you because you don’t know what it is to have grandparents. I feel sorry for you because your world starts only with me and with your mummy.” I didn’t understand at all what he was talking about. I didn’t want him to feel sorry for me. I didn’t feel I was missing anything. But of course he was right. I didn’t have any grandparents. My father’s parents and my mother’s parents had all perished in Auschwitz. And most of my aunts and uncles had also been murdered.

As I matured, I came to know more about Évike. She had been a sweet-natured, rather shy and reserved little girl. She had also been exceptionally intelligent, and though she was too young to have started school, she had actually taught herself to read and write using her storybooks and the daily newspaper. This is important to Évike’s story as I will try to explain later, because since she had learned to read and write, we can actually know a little bit about her from her very own words.

My father was a member of a close and very loving family, who continued to support him and his two brothers while they were in slave labour service during the war. They sent him parcels with food and clothing, and many, many letters. In 1944 alone my father received more than 150 letters and postcards from his family. More than 150 letters. I know this because my father kept them all: he managed to keep them in his knapsack through his entire wartime ordeal. These letters came from his mother and his father and his wife, and yes from his little girl Évike. The little girl who had never gone to school. He kept them, not just during the war, but afterwards too. And, many years later when he saw that I was very serious about writing a book about the family—this was back in 1982—my father told me he still had these letters. I began reading them with him. They were all in Hungarian, so I began to translate them all into English. And while I was doing this, I had a kind of breakdown. Working with the letters prostrated me, almost literally. I couldn’t function for months, because of their impact on me. Because these letters were from the people that my father had been telling me about from the time that I was very young. And when I read them, I saw how right he had been, because indeed, it was a very sad thing that I never knew my grandparents. And here they were, in these letters. I could touch the paper that had been in my grandmother’s hand and in my grandfather’s. I could see what good people they were, how courageous, how very hopeful and determined to find each other again after the cataclysm. They kept on sending my father messages of encouragement that I could read for myself. And I knew what they didn’t know, what they couldn’t know. I knew. I knew that history was going to eat them up. I knew that they were all headed for Auschwitz.

Évike was one of my father’s correspondents. Her notes and letters were enclosed with the grown ups’ letters. She wrote on decorative children’s stationery, very similar to the flowered children’s notepaper my own daughters wrote on when they were little. Miniature envelopes contained Évike’s first written communications to her favourite person in the world. She knew how a letter should look. She wrote my father’s address at his labour service company on the tiny envelopes in block capitals all running together: FOR WEINBERGER GUSZTÁV, MAROS HÉVIZ, MAROS TORDA COUNTY, and on the back she printed her name and return address: WEINBERGER ÉVA EDIT VAJA. Inside she wrote in the same large, block capital letters messages that speak of her love and confidence in her daddy. She clearly adored him: she had named both her teddy bear and favourite doll for him. In her notes she shares jokes, and describes her latest achievements and activities. In one of them, she writes how she lost her first tooth. In another she says that she’s taking good care of her mummy and that she has crocheted a hat for her teddy bear. And in all of them, she signs off: I KISS YOU MANY TIMES YOUR ÉVIKE.

There were three generations of the Weinberger family who were forced to leave their home for the ghetto in Kisvárda on April 25, 1944. Évike had celebrated her sixth birthday six days earlier, on April 19. On April 19 her mother, Mancika, wrote to Guszti that they were packing up their bags and that it was hard to know what to take along. She was particularly upset that she would have to give up her wedding ring, but she wrote, “You will buy me another one some day if God willing, we meet again once more. Today is the darling child’s birthday, we congratulated her in tears, and I wish that all her future birthdays, she will attain under happier circumstances, then today’s, until she’s 120 years old.” Until 120 years old, Évike’s mother wrote. That is the traditional Jewish greeting on someone’s birthday. Both Évike and Mancika would die forty-five days later on June 3, 1944.

The family wrote again, a long farewell letter on April 23 to my father, in which Évike added her own greetings: MY DARLING APUKA HOW ARE YOU I AM THANK GOD WELL, I THANK YOU VERY MUCH FOR THE BIRTHDAY WISHES. I AM VERY SORRY THAT WE CANNOT BE TOGETHER KISSING YOU VERY MANY TIMES YOUR ÉVIKE.

We know what she chose to take with her to the ghetto. In that same letter, her mother wrote that they were all packing their parcels for the big journey. “My poor little Évike has also packed up her Guszti teddy bear and a book, so that I should take it for her.”

There is a final vignette of Évike that I will share with you in a few minutes, but first now I would like to talk about the family I come from.

Évike was a child cherished not just by her parents, but also the whole extended family and especially by our grandparents. I would like to speak about my grandparents. They were very religious people with a great deal of faith in God, but they were also educated people, who could express themselves beautifully in writing. My grandmother Ilona, after whom I’m named, wrote in her farewell letter to my father: “If you could see me, you would say I am a veritable hero and I owe this to the fact that, thank God, I am perfectly healthy and also to my unshakable faith to which I cling. . . . We all have to fortify ourselves so we can bear it all. Don’t worry, I will do everything for the two sweet children [Évike and Marika], after all, they have always been the light of my life, along with all of you.” She promised she would do everything for her two little granddaughters, not realizing that she would be powerless to do anything to help herself or anyone else.

There are many photographs of my grandparents with their two little granddaughters. And in all those photographs, Évike is always sitting on our grandfather’s lap and Marika is always in our grandmother’s lap. They all look very happy and contented together. My grandfather Kálmán was the head of the family—a serious, well-read man who by this time had retired from farming actively, and given over the management of the estate to his three sons. Kálmán wrote long, detailed letters or postcards to them every day that they were away in labour service. He kept on urging them to be strong and he kept on assuring them that the family was well. On this last day in this farewell letter, I think he had no illusions about what was in store, even if he had never heard of Auschwitz. Here are his words: “Let the Almighty in His mercy watch over your precious wife and precious gifted Évike and help you so that you may delight in them for 120 years and that you may find only happiness with them. Thank you, my precious good son for the great joy which you have given us and let the precious Évike and your yet to be born children also give great pleasure to you.”

My heart breaks every time I read these words, and think of the agony that my family went through at that time—the agony that my grandfather must have felt writing these words. It touches me profoundly that my grandfather even had a blessing for me and for my sister Judith, who testified here last week. Because we were the “yet to be born Children,” the children he would never know and who would never know him. Of course he could not imagine that the mother of these children—would not be Évike’s mother, my father’s first wife, Mancika.

I want to say a few words about Évike’s mother, Mancika Mandula Weinberger. She was a devoted daughter to her parents, an adoring wife to my father, and a completely dedicated mother to Évike. She was patient and thoughtful. She knew many languages because she had attended a finishing school in Switzerland where she had mingled with girls from many different nationalities. She was thirty-five years old in 1944, and she was strong and fit, and had she not been the mother of a six-year-old, she would’ve had a chance to live. I don’t think she would’ve wanted to live without her child, but in stark terms, the child whose hand she was holding condemned her to death in Auschwitz.

The cattle car that brought the Weinberger family from the ghetto town of Kisvárda in northeast Hungary contained thirty-four members of my family, of whom two survived the war. One of these survivors was my father’s cousin Susan Rochlitz Szöke. Cousin Susan was nineteen years old and completely traumatized by the horrors of the journey. But still she remembered clearly Mancika and Évike in the wagon. Évike was irritable and tired and thirsty and unable to understand what was happening. She asked over and over again where they were going. And Mancika repeated over and over again, with bottomless patience, “We’re going to a place where we’ll work until we will be together with Apu. Perhaps daddy is already waiting for us there. We’re going somewhere where you’re going to see Apu.”

We all know what happened next. It was not my father who met them on the ramp in Auschwitz. I cannot bear to put words to what I know happened next.

I have been asked to talk about the impact of the Holocaust on me, to talk about how it has damaged me. To try to answer that question places me on the horns of a dilemma. I have not come to Germany to elicit your pity. I don’t think of myself as a damaged person. I am a happy person and I have a full life. It would be ethically wrong to call myself a victim in a courtroom where you are hearing from survivors. I am not a survivor of the Holocaust; I was born three years after the events we are describing. Any pain that I have suffered cannot be compared to their suffering.

But if I’m going to be honest with myself and with you, I must face the fact that indeed the impact of the Holocaust on me has been foundational. The very circumstances of my birth are predicated on the death of others. If Évike and her mother had lived, I would not have been born as myself. If my mother and her first husband had not been separated, but if I had been born to them, I would also not have been born as myself. And yet I feel enormously fortunate to have been born, and to have been born to my parents. And I know I was a great source of happiness to them simply by token of my birth. When he learned that my mother was pregnant with me, my father said to her that he felt the kind of joy that God must have felt on the day of creation. And despite their grief and the enormity of their losses, my parents went on to build a solid new life for themselves and their children in a new country. In the course of building this new life, they never forgot the family members from their former lives, nor what had happened to them. It was important to my parents to communicate to us a rich legacy of family memory.

For the formative years of my life, the Jewish holidays meant sitting at a table for four: my father, my mother, my sister, Judy, and myself. The table would be festively set and there would be a nice meal, during which my father and my mother reminisced about what the holiday had been like in the days before the war. They talked of all the many people who had congregated around the large dining room table back home, and the copious amounts of delicious traditional food. It was as if the Holocaust were a visitor sharing our meal with us.

Before my father died at the age of eighty-four, I had hardly ever attended a funeral. A friend of my parents came to pay a condolence visit during the week of mourning that we call shiva. She had been a child survivor and had lost everybody in her family. When she came into the room where the mourners were sitting on low chairs as is the custom, with all the mirrors in the house covered as is the custom, this friend of my parents made a gesture with her hands to encompass the signs of mourning, and she said, “We don’t know how to do this. We’ve never done this before.” She didn’t have to explain what she meant, because we understood perfectly. Having lost virtually everybody, all at once, my parents’ generation—and by extension, us, their children—had never had a chance to express grief in a normal way, as one does when generations pass away in their natural order. We had never had experience with the normal rituals of mourning, because everybody was already dead.

Nowadays, when my family gathers together to celebrate the Jewish holidays and in particularly Passover, a holiday celebrating freedom from slavery, there are once more three generations grouped around a very long table. There is a passage in the Passover Haggadah in which it says that in every generation a Jew must feel as if he had personally been liberated from slavery. In the era when my father led the family seders, he always paused at this passage to remark that this was not some remote thing that happened thousands of years ago. He said that in our times he and my mother had suffered from a slavery that was incomparably crueler than anything in the time of the pharaohs, and he told us to never forget to guard our freedom and the freedom of others with our last breath.

I think this is what I have come to say to the court: that justice and freedom are our highest societal values. They must be regarded as precious as life itself.

Having the opportunity to tell my family’s story here—having the opportunity to speak to you of Évike, Mancika, and my grandparents—is an affirmation that their lives, so cruelly cut short, mattered. They were not statistics; they were flesh and blood, individuals with personalities, temperaments, frailties, and strengths. There is no way to go back to undo the catastrophe that befell them. There is no way to fix what happened to them. But acknowledging the enormity of what happened to them in this courtroom and before the world is a source of a certain consolation.

After testifying, I emerge from the courtroom into bright sunshine, flooded with relief that my part, for now, is over. It comes as a shock that I had been almost unaware of Groening as I spoke. It was as if he were the least important part of the process, like a pebble caught in the jaws of history that ground my family into pulp.

My husband and I join up with Bolgar—the man who testified before me—and his two children to stroll towards town. Bolgar’s family strides ahead of us, and when we catch up with them, they are deep in conversation with a woman of about fifty. She is telling him that she attends the trial every chance she gets, and was greatly moved by his testimony. “This is so important,” she says to him. “I go home and I tell my children.”

As night falls, we all dine together: witnesses, our accompanying family members, and our legal team. We are joined by sixteen-year-old Anna Werner, who drove from Frankfurt with one of our lawyers to attend the day’s session. What piqued her interest? I ask. She tells me that she had a very good history teacher two years ago in the ninth grade, when the war and the Holocaust were topics on the curriculum. “Our teacher took us through it step by step. We have the impression that it was Germany’s fault and we have to continue to look at this part of our history.”

What struck her about the day in court?

Nodding her head in the direction of Bolgar, she says, “Everyone should hear it from the survivors themselves to understand the pain.”

The next day court is cancelled because Groening doesn’t show, citing ill health. Irene Weiss, a survivor from Washington, DC, who is supposed to testify, is unable to do so in the absence of the defendant. But our lawyers don’t think he is malingering. Walther is convinced that the man is being affected by the victim statements, and believes that Groening will yet make history by admitting to a fuller measure of culpability than he has to date. But that may have to wait: the German court has suggested a new set of dates to run through November. I hope that Walther is right. Nothing can change what happened in 1944, but perhaps Groening will have the decency at least to say the right thing at this late date. He will make history, if he stops parsing the extent of his own guilt by calling himself a small cog in a bigger works. He will make history, if he admits to being an essential part of an evil machine that would not have worked if its small cogs had refused to engage. He will make history, if he does what no SS camp guard has done before him.