The International Criminal Court was established to prosecute the world’s greatest monsters. Last year, after more than a decade in operation, it secured its first conviction—against a Congolese rebel commander named Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, who had conscripted thousands of child soldiers into a campaign of murder, torture, and rape in the mineral-rich borderlands near Uganda.

Just a few months later, the ICC began prosecuting another notorious rebel leader from the same region—Dominic Ongwen, who once served as a senior commander under Joseph Kony in the Lord’s Resistance Army. He also is accused of seizing children from their families and forcing them to perform sadistic cruelties against innocent civilians—and one another—under threat of his own personally administered punishments.

But in one crucial respect, the moral equivalence between the two men is inexact: unlike Dyilo, Ongwen once was a child soldier himself. By all accounts, he was a completely normal, lovable boy who sold crafts at the local market—until he was abducted by the LRA as he was walking between home and school one day.

“On the day of his abduction . . . Mr. Ongwen was ‘too small’ to hike and was carried on the backs of older fighters for several days as they travelled to their main military base,” wrote Globe and Mail reporters Stephanie Nolen and Erin Baines, who visited his home of Gulu, Uganda, in 2008. “Like all abducted children, Mr. Ongwen was ordered to forget his past life. He was told that escape was impossible—his family would never take him back and the government would kill him if he tried to return home. Later, he was told that his family had been rounded up into an internment camp and killed. He was told lies about his whereabouts and forced into a harsh regimen of marches and physical labour that left him exhausted and disoriented. There were constant beatings.”

This is more than just a tragic human-interest backstory. These details fundamentally challenge the presumption that Ongwen was morally culpable for the horrors he committed later in life.

From the age of ten, he was brainwashed with the twisted Christian cult ideology promoted by Kony. The personal values he learned were those of his monstrous LRA den fathers. Escape was utterly impossible, and inflicting cruelties on others was the only means he had of guaranteeing his own survival. In this kill-or-be-killed dystopia, the very notion of individual criminal responsibility becomes an abstraction. It is tempting to suppose that as an adult, Ongwen—having risen through the ranks—might have experienced a spontaneous humanitarian epiphany, refused orders, perhaps even assassinated Kony and brought down the whole murderous LRA. But such heroism is the stuff of action films, not the baseline of human decency required under criminal law.

Since Ongwen’s arrest and transfer to ICC custody, he has recorded a message for his former LRA comrades, urging them, too, to put down their arms. “You wouldn’t believe the bed I’m sleeping in now,” he said. (As NPR’s Gregory Warner noted, “No wonder. It was likely Ongwen’s first real mattress in twenty-five years.”) Enlisting this former child soldier in the battle to win hearts and minds would be a far more morally satisfying denouement than sentencing him at The Hague to prison.

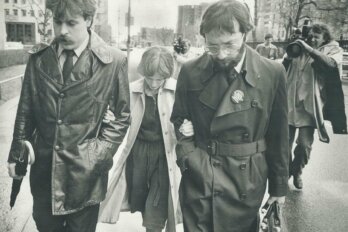

Here in Canada, we are familiar with such vexing moral questions thanks to the case of Omar Khadr, who took up arms in Afghanistan after years of brainwashing by his father, Ahmed, a confidante of Osama bin Laden. Pluck any random schoolchild out of his or her Canadian classroom and set them down in the central Asian hinterland as the ward of a man such as Ahmed Khadr, and he or she would end up in the same orange Gitmo jumpsuit (or worse). The whole edifice of criminal legal theory is based on the presumption that evil is expressed through freely formed intent—mens rea, in the Latin formulation. But with Dominic Ongwen and Omar Khadr, there was no real freedom.

These are extreme examples. But the idea that a person can be programmed for evil from childhood is not confined to the battlefields of Afghanistan and Africa. As Ed Tubb reports in this issue of The Walrus (“Minding the Monster”), many predatory pedophiles were themselves victims of abuse as children. The example of Charlie Taylor provides a particularly chilling case study:

When Taylor was three, provincial authorities labelled him mentally retarded and sent him to the Huronia Regional Centre, originally named the Orillia Asylum for Idiots. From age eight onward, older inmates sexually assaulted him. He continued to endure abuse at various training schools through his teenage years. He escaped periodically—once, he hitchhiked all the way to Sault Ste. Marie—but police returned him to the institutions every time.

As Tubb notes, pedophiles typically experience their attraction to children as a hard-wired sexual preference, entrenched in their brains in the same biologically permanent way as people experience conventional heterosexual or homosexual impulses. But “experiencing abuse at a young age can normalize such behaviour. Some men who would otherwise never act on their urges learn to see the abuse they faced as typical.”

To admit these facts is not to downplay the horrific damage that child molesters inflict, or to argue that these criminals should not be incarcerated when they are caught and convicted. But it does suggest that calling these men monsters and throwing them in cages should not be our only response to the existence of pedophilia. As Jennifer Bleyer recently argued in Slate, pedophiles should have the opportunity to deal with their pathological urges before they offend—something that is impossible within the traditional criminal justice framework of arrest-convict-incarcerate.

Bleyer profiled an organization called B4U-ACT, a Maryland-based group co-founded in 2002 by a clinical social worker and a convicted sex offender with the goal of providing support to those who “self-identify as minor-attracted and who are seeking assistance in dealing with issues in their lives that are challenging to them.” Christian conservatives have denounced mental-health professionals affiliated with B4U-ACT as “predators with Ph.D.s.” But as Bleyer argues, “If even a fraction of [pedophiles] can find safe routes to treatment, and if that prevents any portion of child sexual abuse, the effort seems hard to discount.” Indeed, “the alternative is unconscionable.”

Canada supposedly is a more humane, less moralizing country than the United States. Yet we offer no comprehensive national program to help pedophiles suppress their pathological desires. The closest thing we have is Circles of Support and Accountability, a lightly funded network of volunteers and staffers created two decades ago by a Mennonite pastor. But as Tubb notes, CoSA’s services extend only to convicted sex offenders who are seeking to reintegrate into society following release from prison. And even this modest program is in danger, because most of its federal budget ran out last October.

Given that multiple studies have shown CoSA services are effective at reducing recidivism, such cuts are, to borrow Bleyer’s term, unconscionable—especially for a government that endlessly postures as the great Canadian champion of law, order, and public safety.

“I cannot even begin to comprehend why those who sexually prey on children do the heinous things that they do,” Prime Minister Stephen Harper said in 2013. “The fact is, we don’t understand them, and we don’t particularly care to.”

This posture of wilful, even ostentatious, ignorance is attractive to politicians who cast violent criminals as malignant beasts so contemptible as to be unworthy of ordinary human curiosity. But as the cases of Ongwen and Taylor both show, even the most notorious predators come with backstories worthy of scrutiny, and sometimes perhaps sympathy. In many cases, the evil they do is the same evil that’s been done to them. And when they come forward seeking society’s help in breaking a dark cycle, we have a moral duty to answer the call.

This appeared in the May 2015 issue.