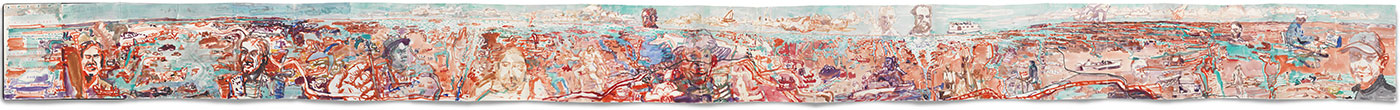

Few landscapes feel more like maps of themselves than the eastern shore of Georgian Bay, Ontario. Its outer reefs; its smooth, extended peninsulas; its maze of islands and their intricate, weather-blown edges can look, from the slightest elevation, as if their details were carefully and precisely rendered by a gifted cartographer.

Artist John Hartman, sixty-four, is a fan of maps. “I love them,” he says in a calm, deep voice. He is a practical man—an explorer, in his way—who uses maps as practical people do: to get to where he’s going, and to remember where he has been. You don’t spend a lifetime of summers amid the hidden shoals and narrow channels of Georgian Bay without knowing how to read charts.

But for Hartman, maps are more than utilitarian—tools to avoid damaged hulls and pranged propellers. He also admires their beauty and their precise representational spirit. He collects them, dreams about them, blends his idea of them with his idea of landscapes.

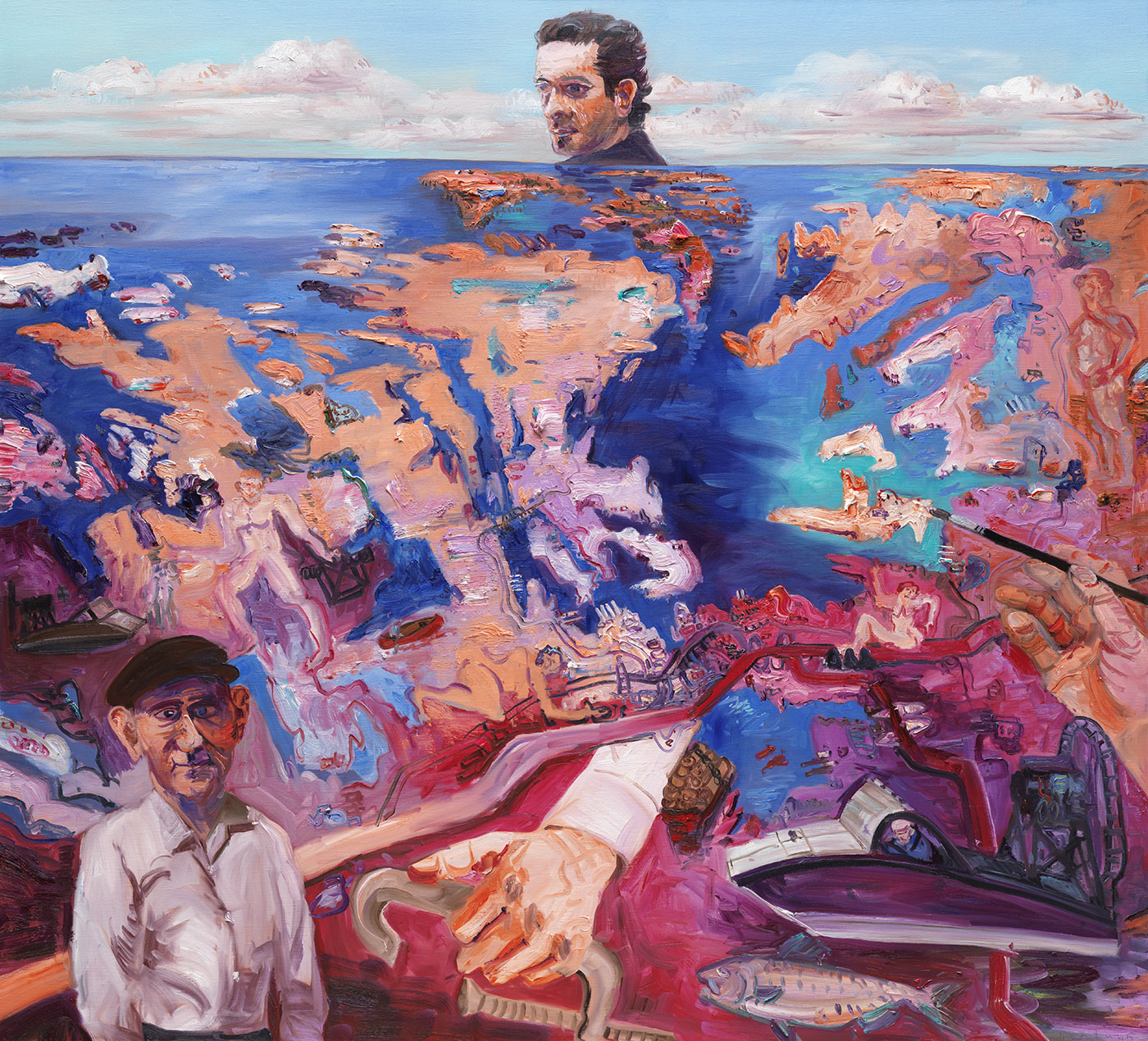

His work is populated with portraits and iconography. In his new paintings of Georgian Bay, he has inserted his parents; the seventeenth-century explorer Samuel de Champlain; the artists Tom Thomson and Doris McCarthy; the novelist Joseph Boyden; and various local boat builders, contractors, marina operators, fishermen, and trappers. They are all characters in the narratives Hartman reads in the landscape.

There was a period in Hartman’s life—brief in the scheme of things, but at the time sufficiently convincing for him to apply to law school—when he thought he might not be an artist at all, at least not professionally. But even then, maps held a power over him. In the ’70s, as a student at McMaster University in Hamilton, and long before he developed his own geography of memory and place, he and his friend Peter Szatmari (now the head of child psychiatry at SickKids in Toronto) studied maps to ward off the realities of winter.

They had both worked at Camp Hurontario, a boys’ camp south of Parry Sound, near the blustery open end of Twelve Mile Bay. Today, it is operated by Pauline Hodgetts and her husband, Don Marston; but in those days it was run by Pauline’s father, a history teacher named Birnie Hodgetts. Birnie was an important figure in the lives of many who spent their Julys and Augusts there, among them John Sewell, once the mayor of Toronto; Monte Hummel, the former president and CEO of World Wildlife Fund Canada; the artist Ed Bartram; and Olympic paddling medallist John Wood. The television host Valerie Pringle worked there; so did her brother, journalist Tony Whittingham. During her own summer employment at Hurontario, Margaret Atwood wrote an operatic sketch for an August performance about a counsellor who sold his soul to the devil for a date with the prettiest waitress. The script, handwritten on blue Camp Hurontario stationery, survives to this day.

For Hartman, Hurontario was a special place. Its wild, majestic location was an attraction, but so was Birnie Hodgetts’s engagingly informal belief that a place so beautiful had a spiritual resonance. He considered outings in rowboats, loaded with oil paints or watercolours, to be as important a part of camp life as canoeing—if only because any attempt to paint or draw a landscape would oblige boys, however minimal their artistic gifts, to examine their surroundings. Today, there are probably men in their sixties who still keep their panels of amateurishly bent pine trees on garishly pink granite shorelines, only because the spray of the whitecaps, or the way the summer light crests the juniper, or the flash of a gull turning in the blue sky was corrected by another artist Hodgetts knew, admired, and invited to visit the camp: A. Y. Jackson.

Camp Hurontario embodied the brief, glorious Canadian summer, and on cold dark winter nights in Hamilton, Hartman and Szatmari reminisced about its rocks and wind and sun, and made an interesting discovery. They figured out that by plotting the routes of canoe trips on topographical charts in the McMaster geography department, they could bring the memories of those camp summers to life.

Years later, as a young artist in conversation with the elderly poet Douglas LePan, Hartman learned the same lesson—only this time the reach of memory would extend far beyond recent summer holidays.

Maps—or, more precisely, the meaning of maps—sit at the centre of Hartman’s work, in part because LePan happened to mention that he sometimes sat in a field on the site of Sainte-Marie-Among-the-Hurons, a seventeenth-century Jesuit mission near Midland, Ontario, and daydreamed about what might have happened there. LePan was fascinated with the textures our imaginations and histories can bring to landscapes. Like Hartman, he was particularly drawn to the elegant, almost oriental minimalism of Georgian Bay’s eastern shoreline. Hartman later told Rosemarie Tovell, a former National Gallery curator of Canadian prints and drawings, that “the penny dropped” for him when LePan made that comment. From then on, maps and landscapes became tracings of each other in Hartman’s world—equally haunted by the ghosts of history and by the memories of more personal provenance.

In the years since that encounter with LePan, Hartman has worked in places as untamed as Newfoundland; Scandinavia; and the Hebrides, Scotland; and as cosmopolitan as London, New York, San Francisco, and Vancouver. He is represented by galleries in Toronto, New York, and New Orleans, and by Canadian standards he is a successful artist—successful enough to have been underestimated by those whose cultural positions oblige them to regard commercial triumph with suspicion.

Not that being underestimated surprises Hartman. He knows that any contemporary painter who spends time in a Chestnut canoe exploring Georgian Bay is going to call to mind you-know-who—and an association with the Group of Seven, however dynamic or challenging or even oppositional, is not considered hip among the more fashionable denizens of the Canadian art world. On top of which, Hartman’s distinguished grey hair, friendly face, courtly manner, and characteristic T-shirts and black jeans don’t come across as very bohemian.

But he is by no means a romantic, rurally fixated artist. In fact, you could argue that the period in his career at which he most confidently and audaciously hit his stride was between 2004 and 2012, when he painted a series of oils and watercolours of cities as varied as Toronto, Hamilton, Vancouver, Halifax, New York, Boston, London, and Glasgow. He brought to these centres the same idiosyncratic point of reference with which he was already addressing landscapes: that how we remember places is at least as interesting as what we remember. “There always has to be one essential characteristic about a city or where it is that I can paint towards,” he told the writer Noah Richler at the time. “With Manhattan, it had to do with the remarkable density of the buildings. In Halifax, it has to do with the incredible site the city sits on.”

Hartman’s city series reveals a vibrantly askew, aerial, almost Richard Scarry–like enthusiasm for the busyness and bigness of urban form. It is the work of someone who enjoys the charge that cities bring to his life. But his visits to those places are simply that: visits. In many ways, John Hartman has stayed put.

He lives and works just west of Midland, the Georgian Bay town of 16,000 where he was born and grew up. (His father was an accountant, and in the summers his parents ran a girls’ camp near Port Severn.) He now summers with his wife and family not far north of Camp Hurontario, where as a young man he became an art instructor. His predecessor there was David Blackwood, the now well-known Newfoundland artist.

“Blackwood was an influence,” he says, “mostly because he told stories with his etchings, and he used his childhood in Wesleyville, in particular, and the outport culture of Bonavista Bay, in general, as sources for these stories.” But narrative art was by no means an exclusive area of interest for Hartman. As a student, he pursued inspiration with a voracious, wide-ranging, well-travelled curiosity. He was thoughtful, articulate, and informed about art history, and he remains deeply respectful of the those who have influenced him: David Milne, J. M. W. Turner, Philip Guston, Albrecht Altdorfer, Chaim Soutine, and Oskar Kokoschka among them.

The jagged shore of the Georgian Bay archipelago is the subject of Hartman’s most recent work: nine large, contiguous oils that map the landscape in which he has invested so much of his creative energy. For him, it is a part of the world that has a meaning that’s even greater than its considerable physical beauty. “I believe we all have a home landscape,” he has written, “a place from our childhood, whose light, space and scale are the benchmark for all other landscapes. We all carry our home landscapes around inside us.”

Still, you can’t call John Hartman parochial. What you can say is there’s something local about who he is and what he does. Very local. It has its origins in an understanding he has had all his life: that works of art, like maps, are as big as they are small. Where he is and who he is are not very different questions in his world, and were you to ask him to show you where he lives creatively he would not hesitate long before flipping the pages of an atlas to Ontario, and running his finger along the eastern shore of Georgian Bay. It would be like tracing a line.

This appeared in the September 2014 issue.